Innovation Adaptation

Lesson 2.3: Innovation Adaptation

In the first step of our ladder of opportunities (see Figure 2.1) we looked at job crafting (in the previous module). Job crafting refers to the act of changing one’s job in a personalized way, with an intention of improving performance for the organization and quality of work life. At this stage, we will move a step up and focus on innovation adaptation where employees will scan their internal/external environment to identify any adaptation opportunities to be implemented in their workplace. Of course, in response to such needs as improving performance, introducing new products, or solving an operational problem.

As with most innovations, there will be opportunities to test them out and to improve upon them. Innovation Adaptation is the process of taking ideas from a previous innovation for use as core concepts that can be tailored to fit the challenges and context that are now being addressed. Organizations scan the market on a regular basis to identify what their competitors are working on to stay one step ahead of them. What we often observe is that one organization will introduce a radical innovation and other organizations will follow suit and copy/adapt the idea with some variations. However, organizations must ensure that they are not violating copyright or patent laws as they differentiate or iterate on other organizations’ innovations. For example, iRobot’s Roomba,

was previously introduced by Electrolux and Dyson but unsuccessfully. Since Roomba’s introduction, many other companies have introduced robotic vacuums differing in various attributes such as price point or functionality. Nevertheless, iRobot has kept its market leadership over the years.

To better understand the process of employee-led innovation adaptation, consider the following Case Study:

I. Case Study: From Red Box to Orange Box

Our first case study of Innovation Adaptation will illustrate some of the benefits and challenges of adapting an innovation from one context to another. We begin with an innovation in work practice at Adobe Systems, inventors of the PDF format and producers of the software packages Photoshop and Acrobat Reader (which most of us use to read PDF files).

Use this link (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VU4XYGuUh_0) from the Red Box image to the right to see a short video introduction by the originator of the innovation. This initiative was wildly successful, and Adobe made it available for other organizations to use with the name Kickbox.

Now that you understand the basic structure of the innovation, let’s look at an adaptation by another technology company, Mastercard International (in the financial services sector). Below, you’ll be asked to identify some of the changes they made to fit the Kickbox ideas into their different context, and then to pick which company you would rather work for based on what the changes tell you about the two companies.

Mastercard’s Orange Box

At Mastercard, individuals or teams with promising ideas are awarded an Orange Box containing a $1,000 pre-paid card and tools to help them explore their idea and hone a pitch in 60 days. Almost all participants form teams because the time commitment for the “promising ideas” is so large.

If the pitch is approved, the team receives a Red Box, which contains $25,000 and 90 days to develop their project further, with the goal of presenting the concept to the Mastercard Innovation Council.

Finally, the projects that win the council’s approval receive the ultimate prize: A Green Box. These ideas are accepted for “incubation” with MasterCard’s commitment to adopt the idea and to invest appropriate resources to support it.

During the adaptation process of the Red Box to Orange Box, the Innovation Council leader initiated a number of other changes to make it more “Mastercardy” – fitting in to the company culture and structures this resulted in the following additions to the Orange Box in comparison to the original Adobe Red Box:

- Mentor: Inside a packet emblazoned with the warning “In case of emergency, break seal” is the name of a company employee assigned as a mentor. These mentors are assigned to teams to actively guide them through the first 60 days with the box, and are accountable for the quality of the output once their help is requested.

- Timer: A countdown timer is set to the end of the 60 days when the presentation of results is to occur.

- 60-Day Guide: The box contains several booklets with titles like, “Bad is Good: Go on, get the bad ideas out of your system.” Another booklet outlines what makes a good idea.

- Mandatory Check-ins: Even though each team has a mentor, they still have mandatory check-ins with the leader of the Innovation Council. According to Mastercard “The intention is to ultimately make sure we have something tangible at the end of the 60-days to react to, so we can decide if we’re going to give them a Red Box, which has 25 times the money in it. It’s stepping them toward the idea of an incubation.”

Excerpted from How Mastercard Adapted the Adobe Kickbox Innovation Kit. Blog post at Innovation Leader9[NewTab], 6/4/2020

Application of Concepts

From this description of the Mastercard Red Box experience, list the two adaptations you think would be most important to you if you were a Mastercard employee given the information presented here.

Feedback: Your answer will be very personal. Here are two examples:

You may have noticed the increasing degree of structure in the Mastercard version, with three stages (Boxes) and a stronger degree of oversight (Mentor, Innovation Council).

You may have also noticed the stronger emphasis on collective innovation, through the expectation for team work rather than just individuals and the early involvement of others outside the team (the Innovation Council and its leader).

Application of Concepts Based on the examples from Kickbox and Mastercard, how do you think the two companies’ workplace cultures differ? Which do you believe would be a better fit for you? Why? (If neither is a fit for you, please explain).

Feedback:

There is, of course, no ‘right’ response to this question: Different people will benefit from different kinds and degrees of structure in the workplace innovation process.

Consider, also, that the differences between the Kickbox models indicate that the organizations were asking different questions. The original Adobe Kickbox model seems to ask, “What if our employees felt more empowered to engage in self-directed innovative behaviour?”

On the other hand, Mastercard seems to address a bigger “what if?” question such as “What if our employees felt more empowered to engage in self-directed innovative behavior and were more supported by our management structures in seeing those ideas through to implementation”? …

For yet another adaptation of the KickBox concept, review this one from high-tech company Cisco Systems [NewTab]. Consider how this example reflects the company’s distinctive culture and processes.

Key Lessons Cisco’s Use of the Kickbox Model:

- You have to adapt the innovation to your organization’s culture, processes, etc. A program like Kickbox will be a success if it feels authentic to your company, so it’s important to tailor Kickbox to fit into your culture. Every company has a way it communicates with employees. At Cisco Systems, they kept the structure, but modified the language so that they talked about things in a way that would resonate with employees (Goryachev, 2017).

- In any adaptation,it’s necessary to maintain the core principles that made it work: “While adapting is an essential part of success, it is important to keep the core of the program” (Goryachev, 2017). According to Mark Randall, the originator of the innovation at Adobe Systems, “If your program does not have the main elements – being available to all employees, having no limits on projects pursued, and including a seed budget in advance of having ideas – then you just have some colored cards and a box, but you don’t have Kickbox” (Goryachev, 2017). (Refer back to this comment when you are asked to fill in your responses to the third example below, from a university context.)

II. Case Study: Innovation Adaptation in Post-Secondary Education Teaching and Learning through Peer Instruction

Peer Instruction [PI] was developed by Eric Mazur in the early 1990’s for use in large lecture classes of his introductory physics courses at Harvard University with the aim of engaging students in their own learning in lecture-based classes. In a PI class, the instructor delivers short lectures (7–10 minutes) followed by a series of multiple-choice conceptual questions (Crouch and Mazur, 2001) based on the lectures. Students first think about the question and answer it individually – often using a personal response, or “clicker,” system – then discuss their answer with a nearby classmate, and, finally, revise their answer (Dancy et al, 2016).

Based on student responses to the multiple-choice questions, the instructor may decide to move on to the next topic or to continue with the current topic. The goal is to ensure that students are becoming more comfortable with the content. Research studies have shown that PI is successful in improving student learning of physics content and reducing the gender gap [related to success in Physics courses] (Lorenzo et al 2006).

Innovation Adaptation: What is Core?

Suppose one of your instructor’s is trying to adapt Peer Instruction in one of your classes. There are a number of good reasons to consider modifying the original innovation-Peer Instruction:

- Differences in learning skills, learning styles or background Physics knowledge between different countries, institutions, degree programs etc.,

- Cultural differences, e.g., students from a specific country may have different expectations than international students

- Different disciplines may require different approaches to teaching and learning; i.e., if the class is in a subject area other than Physics, other adaptations to the model may be required. (e.g., Luxan, 2018).

- Additional research might be applicable to you class and therefore would require adjustment of the Mazur model (e.g., Shell and Butler, 2018).

When considering how the instructor might adapt the PI model for specific students, there is also the possibility that some adaptations will introduce obstacles to achieving the intended success of the innovation. A common example is an adaptation that drops or replaces one of the core features and then fails to achieve the desired improvements in learning. When that happens, the instructor making the adaptation may believe that peer instruction doesn’t work as it should with realizing how their approach invalidated the original results.

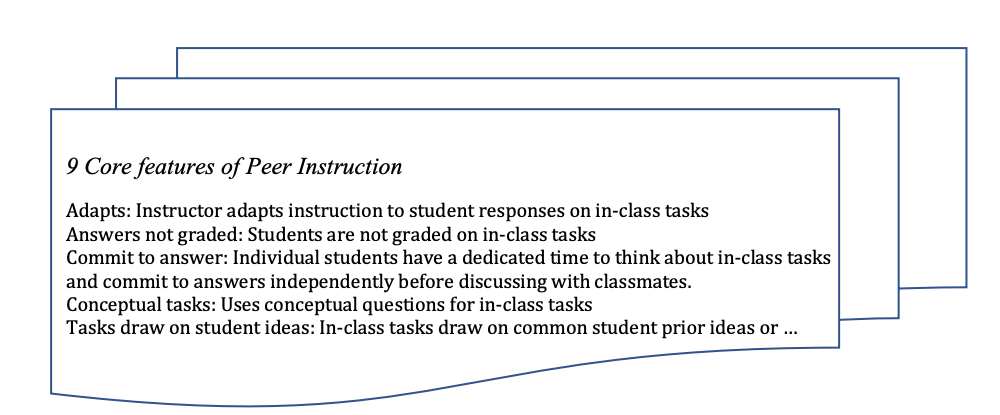

For Peer Instruction in Physics, there are nine core features such as those shown below.

This list comes from a research study by Dansi et al. (2016) exploring how well Physics instructors preserved the 9 Core Features when they made adaptations designed to fit into their classroom contexts. Some of the instructors reported that they continued to use Peer Instruction (70%) while others indicated they had tried it but no longer used it (30%).

From detailed interviews about how Peer Instruction had been implemented, the researchers calculated the following results for how many of the core features were preserved:

| Core Features | Proportion of Instructors |

|---|---|

| 7 – 9 | 33% |

| 4 – 6 | 43% |

| 0 – 3 | 4%

(and yes, there really was someone claiming to use PI with 0 of the core features included !) |

In addition, none of the instructors who described themselves as former users of Peer Instruction had actually used more than 6 of the 9 core features. Given the varied use rates of the model, the question becomes whether instructors presumed the model did not work for them or if they used the model but did not adapt it for their specific group of students.

To summarize, one of the results from this case study was a set of guidelines for documenting the essentials of an innovative instructional (Khatri et al, 2016) to increase the chances of success for future adaptors. You won’t always be this fortunate with your Innovation Adaptations, as many innovators describe their innovation in terms of “here’s what we did and what resulted,” without explaining – or perhaps even realizing – which elements were core to the success. Additional study and context is always helpful when trying to modify an innovation, especially when it is being adapted for use in a different situation.

Application of ConceptsRecall from Lesson 2.2 that the innovation challenges and activities in Innovation Adaptation expand on the Job Crafting challenges and activities on two dimensions: (i) increased team size and diversity and (ii) increased complexity and uncertainty. For each of these dimensions, describe the effort required in Innovation Adaptation for Peer Instruction in a course you are taking.

Feedback:

(i) Team Size and Diversity: There will be three main participants involved in this Innovation Adaptation:

- the university as “Manager” specifying the work to be achieved (e.g., the description in the University Calendar of the course topics and learning outcomes) and the resources available (e.g., time available for innovation, teaching assistant support)

- the instructor as “Worker” who has some measure of discretion about how to carry out the work of teaching to align with personal teaching strengths, topic of the specific class session, etc.

- Students as “co-workers” in the work of learning are critical to the desired results. Adding students into the context of the work of learning offers new perspectives and issues for any planned changes in the work of teaching and learning. For example, for some students the very idea of a change in their customary learning experiences can provoke resistance to innovation unless the benefits to them are clear and compelling (e.g., Ellis, 2005). In other cases, student learn better with specific styles of teaching and therefore they might be averse to the innovation(s).

(ii) Complexity and Uncertainty: A new instructional method must improve experiences and results across these three team elements (manager, worker and co-workers) and within the diverse student group who will likely have differing perspectives on what they consider to be valuable results and rewarding experiences. Any proposed innovation will have to be tested in low-risk settings first to avoid imposing undue risk on students.