Phillip’s Health Part A: Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

New Community… New Life

- Phillip moved to Toronto

- Found a community that accepted him

- Exciting time for Phillip – drinking, drugs, multiple same-sex partners

- Soon turned to IV drugs

- No contact with his family

CC-BY-2.0

Phillip Comes Down with the ‘Flu’

- Phillip is now 29 years of age

- Comes down with flu-like symptoms

- These symptoms last a few weeks

- Close friends are concerned about Phillip’s weight loss

- They suggest he get tested for HIV

Phillip’s Flu like symptoms

- Fever

- Chills

- Rash

- Night sweats

- Muscle aches

- Sore throat

- Fatigue

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Mouth ulcers

Fast Forward 10 Years….

- Phillip is feeling unwell

- Lost even more weight

- Tired all the time

- Noticed ‘blotches’ on his face & in his mouth

- Phillip sees a physician at a local clinic

- Doctor orders tests to confirm his suspicions of HIV/AIDS

What is HIV?

- HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system

- If HIV is not treated, it can lead to AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome)

- There is currently no effective cure. Once people get HIV, they have it for life

- But with proper medical care, HIV can be controlled

- People with HIV who get effective HIV treatment can live long, healthy lives and protect their partners

Where did HIV come from?

- HIV infection in humans came from a type of chimpanzee in Central Africa

- The chimpanzee version of the virus (called simian immunodeficiency virus, or SIV) was probably passed to humans when humans hunted these chimpanzees for meat and came in contact with their infected blood

- Studies show that HIV may have jumped from chimpanzees to humans as far back as the late 1800s

- Over decades, HIV slowly spread across Africa and later into other parts of the world. We know that the virus has existed in the United States since at least the mid to late 1970s

Testing for HIV: Blood & Saliva tests for Phillip

Antigen/Antibody Tests

- These tests usually involve drawing blood from a vein. Antigens are substances on the HIV virus itself and are usually detectable — a positive test — in the blood within a few weeks after exposure to HIV.

- Antibodies are produced by your immune system when it’s exposed to HIV. It can take weeks to months for antibodies to become detectable. The combination antigen/antibody tests can take two to six weeks after exposure to become positive.

Antibody Tests

These tests look for antibodies to HIV in blood or saliva. Most rapid HIV tests, including self-tests done at home, are antibody tests. Antibody tests can take three to 12 weeks after you’re exposed to become positive.

Nucleic Acid Tests (NATs)

These tests look for the actual virus in your blood (viral load). They also involve blood drawn from a vein. If you might have been exposed to HIV within the past few weeks, your doctor may recommend NAT. NAT will be the first test to become positive after exposure to HIV.

Other Possible diagnostic tests:

- Tuberculosis

- Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C virus infection

- STIs

- Liver or kidney damage

- Urinary tract infection

- Cervical and anal cancer

- Cytomegalovirus

- Toxoplasmosis

Testing for HIV: ELISA & Western Blot

ELISA – Enzyme Immunoassay

- One of the most popular tests for HIV

- Detects antibody

- Can give false positive results

Western Blot

- Important confirmatory test

- Used to confirm positive ELISA

Testing for HIV: PCR

- Detects viral load

- HIV RNA should be quantified before starting treatment, and monitored continuously every few weeks

- LOWER VIRAL LOAD = BETTER CLINICAL OUTCOME

- PCR results are given by a standard curve and amplification plot

- Plasma or EDTA vacutainer tubes

- Must be spun, and stored properly to avoid RNA degradation

- Precautions must be taken to avoid contamination

Phillip’s symptoms appeared to be nonspecific at first

- Active replication of the virus only lasts a few weeks 🡪 body will start producing antibodies

- Opportunistic diseases are an issue without adequate treatment

- CD4 levels somewhat stabilize while the virus is dormant 🡪 CD4 count should always be above 500 in healthy individuals!

Phillip’s doctor conducts further testing

To determines the stage of Phillip’s disease & the best treatment options, the following tests were conducted.

CD4 T cell count

CD4 T cells are white blood cells that are specifically targeted and destroyed by HIV. Even if you have no symptoms, HIV infection progresses to AIDS when your CD4 T cell count dips below 200.

Viral load (HIV/RNA)

This test measures the amount of virus in your blood. After starting HIV treatment the goal is to have an undetectable viral load. This significantly reduces your chances of opportunistic infection and other HIV-related complications.

Drug resistance

Some strains of HIV are resistant to medications. This test helps your doctor determine if your specific form of the virus has resistance and guides treatment decisions.

Stages of HIV

Stage 1: Acute HIV Infection

- People have a large amount of HIV in their blood. They are very contagious.

- Some people have flu-like symptoms. This is the body’s natural response to infection.

- But some people may not feel sick right away or at all.

- If you have flu-like symptoms and think you may have been exposed to HIV, seek medical care and ask for a test to diagnose acute infection.

- Only antigen/antibody tests or nucleic acid tests (NATs) can diagnose acute infection.

Stage 2: Chronic HIV Infection

- This stage is also called asymptomatic HIV infection or clinical latency.

- HIV is still active but reproduces at very low levels.

- People may not have any symptoms or get sick during this phase.

- Without taking HIV medicine, this period may last a decade or longer, but some may progress faster.

- People can transmit HIV in this phase.

- At the end of this phase, the amount of HIV in the blood (called viral load) goes up and the CD4 cell count goes down. The person may have symptoms as the virus levels increase in the body, and the person moves into Stage 3.

- People who take HIV medicine as prescribed may never move into Stage 3.

Stage 3: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- The most severe phase of HIV infection.

- People with AIDS have such badly damaged immune systems that they get an increasing number of severe illnesses, called opportunistic infections.

- People receive an AIDS diagnosis when their CD4 cell count drops below 200 cells/mm, or if they develop certain opportunistic infections.

- People with AIDS can have a high viral load and be very infectious.

- Without treatment, people with AIDS typically survive about three years.

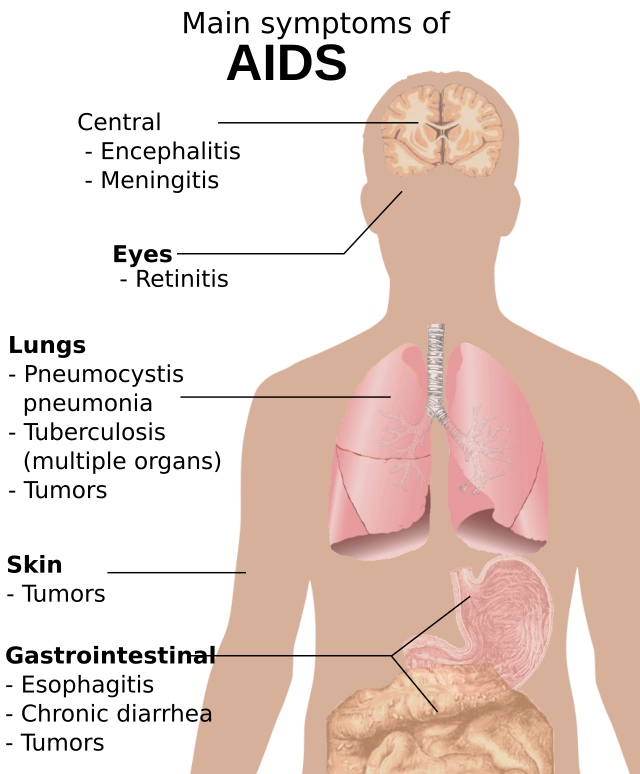

Symptoms of AIDs

- Rapid weight loss

- Recurring fever or profuse night sweats

- Extreme and unexplained tiredness

- Prolonged swelling of the lymph glands in the armpits, groin, or neck

- Diarrhea that lasts for more than a week

- Sores of the mouth, anus, or genitals

- Pneumonia

- Red, brown, pink, or purplish blotches on or under the skin or inside the mouth, nose, or eyelids

- Memory loss, depression, and other neurologic disorders

Factors that can increase or decrease HIV risk

Increases HIV Risk

Viral Load

- Is the amount of HIV in the blood of someone who has HIV. Get your viral load checked at least twice a year.

- The goal of HIV treatment is to reduce viral load.

- The higher the viral load, the more likely transmission of HIV is.

- Earliest phase of HIV infection has a very high viral load.

- Taking HIV medications will provide the greatest chance to lower viral load.

- Using a condom the right way every time can protect from transmission.

- Negative partner can take a daily pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Sexually transmitted disease (STDs)

- Spread from person to person through contact with genital fluid or through ski-to-skin contact.

- HIV is considered an STD if transmitted through sex.

- If sexually active get tested for STDs regularly

- Always use a condom

- Get vaccinated for hepatitis A or B or HPV

Sex Partners

- Sexual partners with different HIV status.

- Having more than one partner.

- Power differences in relationships can also make it harder to have safer sex.

- Choose less risky sexual behaviors.

- Use condoms the right way every time.

- Get tested and encourage your partner to get tested (HIV & STDs).

Sharing needles, syringes or other drug injection equipment

- Using a needle or syringe after someone else use it to inject drugs, medicine, for tattoos or piercings.

- Letting someone else use a needle or syringe after you have used it.

- Never share your needles, syringes or other injection equipment.

Alcohol & Drug Use

- When drunk or high, more likely to make decisions that put you at risk.

- There is therapy & other methods available to help stop or cut down on alcohol & drug use.

Decreases HIV Risk

- Abstinence

- Choosing less risky sexual activities

- Taking medicine to prevent or treat HIV

- Using condoms

- Reducing the number of partners

- Partner communication & agreements

- Male circumcision

Which of these risk factors is relevant to Phillip’s case?

Treating Phillip

There are many medications that can control HIV & prevent complications. These medications are called antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Phillip was started on ART and given a combination of three or more medications from several different drug classes. Two drugs from one class, plus a third drug from a second class.

The goal was to lower the amount of HIV in the blood

Classes of Anti-HIV Drugs

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs): Turn off a protein needed by HIV to make copies of itself.

Nucleoside or nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs): Are faulty versions of the building blocks that HIV needs to make copies of itself.

Protease inhibitors (PIs): Inactivate HIV protease, another protein that HIV needs to make copies of itself.

Integrase inhibitors: Work by disabling a protein called integrase, which HIV uses to insert its genetic material into CD4 T cells.

Entry or fusion inhibitors: Block HIV entry into CD4 T cells.

Schematic description of the mechanism of the four classes of antiretroviral drugs for HIV

Phillip struggles with his diagnosis

Philip began to struggle with social anxiety and depression due to his diagnosis..

He has not found social support in his family but is determined to follow through with the treatment regimen prescribed by his physician.

Sexual Risk Behaviours of LGBTQ

- Sex initiated during adolescence

- Older sexual partners

- HIV barrier methods adopted subsequent to sexual debut

- Many lifetime sexual partners and encounters

- Sex for goods

- One partner at risk for HIV

- Unprotected sex during the past 3 months

LGBT Risk Factors for Mental Health Problems

Harassment & discrimination in education

- About three quarters of LGBT students report having been harassed at school; even worse, 35% have experienced physical assault, and 12% have been the victim of sexual violence at school.

- Harassment and assault, especially when it occurs in what should be a safe and supportive setting, can have serious impacts on mental health such as fear, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Institutional discrimination

- The LGBT population experiences institutional discrimination in a variety of situations and settings such as the workplace and places of worship.

- LGBT individuals are frequently denied career advancement or equal compensation compared with their gender-conforming peers, and their unemployment rate is double that of the general population

Health disparities

Discrimination in health care settings endangers LGBTQ people’s lives through delays or denials of medically necessary care. Transgender patients may require medical interventions such as hormone therapy and/or surgery.

Other common barriers

Discrimination, lack of insurance, lack of cultural competence/sensitivity by health care providers, and socioeconomic barriers such as low income, lack of transportation, and inadequate housing.

Family rejection

- Family rejection can also lead to long-lasting psychiatric problems later in life.

- Rejected individuals may develop depression and low self-esteem and may turn to alcohol, cigarettes, or drugs, smoking cigarettes to cope.

History of trauma

- Many individuals in the LGBT population have experienced past physical assault and harassment.

- Past trauma compounds any current trauma, exacerbating anxiety about future safety, especially in a political climate that feels hostile.

Microtraumas/Microaggressions

- People who identify as LGBT often experience brief, subtle expressions of hostility or discrimination.

- While microaggressions are often associated with racial/ethnic minorities, they can also impact LGBT and other marginalized populations, and cumulatively they can take a toll on mental and physical health.

- LGBT people who experience microtraumas may not meet diagnosable criteria for PTSD yet suffer tremendously from minority stressors such as from internalized phobia, rejection sensitivity, marginalization, and discrimination both in their personal life and health care settings.