Changes to Course Elements

Our UDL-informed discussions led us to significantly revise four course elements to better engage students and improve our assessment of student learning.

1. The On-The-Land Exercise

“I believe the subject matter of the course conveyed rather vast information with a clear and enticing presentation, which made the class easy because it was enjoyable.”

The first was a complete change to a key experiential learning assignment. For three years, we had the students participate in either the Kairos Blanket Exercise or a local version developed by Trent’s First Peoples House of Learning. This assignment engaged students in an exercise designed to help them emotionally understand the impact of colonialism upon Indigenous peoples. While meaningful, the exercise was not suited for the volume of students we were now working with, and as a result, its impact was muted. At the same time, the exercise did not engage in one of the core learning outcomes, which was to understand the land from an Indigenous perspective.

Our discussion of learning outcomes, assignments, and evaluation led to creating the “On the Land” media assignment. This assignment asks students to read and watch material in preparation for the exercise, to engage in the physical activity of walking, observing and listening to their environment, and to record their observations and reflections in video and written form using an Indigenous framework. The assignment reflects multiple modes of material presentation and engagement as well as multiple modes of presentation of learning. The use of the Medicine Circle as an analytic framework helps students to connect their learning in a holistic and narrative fashion.

In this assignment, students work in pairs and go out on the land to engage with nature. They then report on their experiences using the concepts they have been exposed to in lectures, readings, and seminars. In a short video, students present their learning reflections through video, still images, and their voices. The result is a relational experience that challenges students to engage in content recall, concept synthesis, and critical analysis. Students present their videos to their peers and discuss their artistic intent behind the video. This exercise helps students to see the land through Indigenous eyes and to learn how to convey their understanding through story, a key way in which Indigenous knowledge (IK) is transmitted.

Here’s the instructions to the students:

*Click on the heading below to reveal more information about the instructions.*

2. The Use of an Indigenous Analytic Frame

“A fantastic course with incredible emotional impact. Indigenous Knowledge component was not only informative but also very useful. This element created a balancing light to onslaught of WTF moments.”

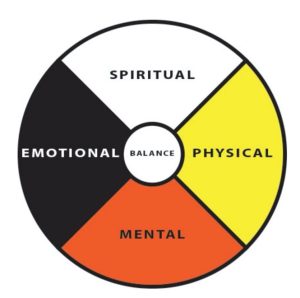

The second change was the explicit use of the Medicine Circle, conceptualized in the course as the four directions analytic model, to reflect the use of IK as an informing element of the course. The use of the circle, the four circle quadrants and the movement through time enables students to visually present their findings and reflections in a disciplined fashion that demonstrates their interconnectedness. Students use a combination of text and diagrams to present their understandings and visually illustrate the connections between various aspects of social phenomena.

From our course syllabus:

Indigenous knowledge is based on principles of holism and interconnectedness. We have developed a way of thinking about social phenomena and social issues based on an Indigenous concept: the Medicine Circle.

We use the Medicine Circle as a way of thinking about and analyzing social phenomena and issues. Our Medicine Circle is derived from Anishinaabe (Ojibway) and Nehiyawak (Cree) teachings. Social phenomena contain four primary aspects: physical, mental, emotional and spiritual. They are also situated in time, which moves from past to present to future. Using the Medicine Circle, we can organize our thinking and analysis in a systematic fashion.

Medicine Circles help us to understand the interconnectedness of things, to see or understand things we can’t quite see because they are ideas and not physical objects. The Medicine Circle is a tool for teaching, learning, contemplating and understanding our journeys at individual, band/community, national, global and even cosmic levels (Calliou, 1995, p. 51). In our approach to learning, everything begins with IK. It is the foundation that supports our implementation of Universal Design for Learning.

We can look at the long assault and the great healing using the Medicine Circle. Each of their actions, residential schools, Indian hospitals, community development, and the relocation of the Inuit, for example, will impact the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual aspects of Indigenous peoples. The impact is not a one-time event but is spread out over time. A four directions approach, based on the medicine circle, provides us with a disciplined and structured way to organize our thinking.

We can look at the long assault and the great healing using the Medicine Circle. Each of their actions, residential schools, Indian hospitals, community development, and the relocation of the Inuit, for example, will impact the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual aspects of Indigenous peoples. The impact is not a one-time event but is spread out over time. A four directions approach, based on the medicine circle, provides us with a disciplined and structured way to organize our thinking.

3. Student Assessments

“I like that weekly content is tested at appropriate intervals, and that papers focus on understanding rather than memorising specifics.”

Our third change was assessment of student learning including the final examination. We endeavoured to ensure that students could represent their knowledge in a wide variety of forms. We developed weekly online quizzes to help students understand key concepts and ideas based on content recall principles and practices. We also assigned reflective exercises like the “On-the-Land” exercise described above and a research paper that required students to examine their own communities to identify Indigenous presence and present their reports in both oral and written form. The sheer size of the class confounded us as we discussed how to help students make sense of the material they learned. We wanted to develop an assessment that helped students internalize their learning in a manner consistent with Indigenous learning theories. We experimented with three approaches to a final exam: no exam, a sit-down written exam, and a take-home exam. We discovered that first-year students are likelier to skip class when there is no final examination. We also discovered that our course was different from other first-year courses. Our assignments, informed by Indigenous learning theories, ask students not just to recall information but to analyze and create their own understanding of the material. Indigenous Elders teach through stories and ask students to tell them how they interpret their story and what its meaning is. Our final exam asks students to reflect on the course material, explain what they learned, and present their learnings in a coherent story. The final exam enables students to present their learnings not as recall exercises in responses to questions but as exercises that enable students to determine the best way for them to demonstrate their learning.

The principles of UDL helped us to again think of multiplicity and flexibility and to find ways to support students in demonstrating their learning in multiple ways. Giving students flexibility around time was important. Students are given three days to complete the examination. As this course focuses on reconciliation, students are tasked with creating their personal responses to the challenge of reconciliation. They must reference the sources used in the content of the lectures, readings, and seminars. The exam enables us to assess their understanding of the course material and their ability to convey that understanding in a coherent narrative. It also allows for a wide, creative approach to conveying that understanding and encourages reflection and synthesis, not just content recall.

4. Student Participation

“I think the course has challenged me in a good way.”

The fourth revision was to our method of assessing student course participation. Conventionally, grades were given for participation divided equally between lecture and seminar attendance and seminar participation. Taking an Indigenous lens to the issue, we approached the issue through the notions of contribution and reciprocity, two key values embedded in traditional Indigenous teaching. Traditional Indigenous teachers see education as requiring reflection on what has been heard to make sense of it in one’s own life. Indigenous teaching is more than just the acquisition of facts; it asks students to continually reflect on what they have heard to deepen their understanding. Education is not a passive activity but one that involves all aspects of the self: mind, body, emotion and spirit. Learners are also expected to help others to learn.

As a result of these teachings and the UDL-informed discussion process focused on multiplicity, we renamed this assessment “contribution” and asked students to prepare a statement of learning and contribution to illustrate, with five examples, what they learned and how they contributed to the learning of their peers. Students found the second aspect, how they contributed to the learning of their peers, challenging as they generally see education as something focused on their professor or seminar leader.