3 Reading #3: The Language of Responsibility

Language of responsibility essentially means taking responsibility for your own thoughts, feelings, and actions and understanding that you have no control over what another person thinks, feels, or does. It is also about being clear and direct. This is a key skill that can really help you to create a supportive climate. One of the ways to demonstrate language of responsibility is to to use “I” language instead of “You” language. When you use “I” language you are describing your own thoughts, feeling and actions. When you use “You language you tend to blame other which can contribute to a hostile environment.

Start this section by reviewing this video and reflecting on your own communication style. Again, you might recognize some of your habits here (for better or for worse!). This is OK, we all have things that we have to work on! We’re never finished growing. It matters if your heart is in the right place and your coming from a place of genuine desire to improve.

“It” statements

Notice the difference between the sentences of each set:

- “It bothers me when you’re late.” vs “I’m worried when you’re late.”

- “It’s nice to see you.” vs “I’m glad to see you.”

- “It’s a boring class.” vs “I’m bored in the class.”

“It” statements replace the personal pronoun “I” with the less immediate and vague word it. By contrast, “I” language clearly identifies the speaker as the source of a message. Communicators who use “it” statements avoid responsibility. To ensure that you own your own thoughts, behaviours , and feelings use “I” language whenever possible.

“But” statements:

These statements take the form “X but Y”. They can be confusing. A closer look at “but” statements explains why. In each sentence, the word but cancels out the thought that precedes it:

- “You’re a really great person, but I think we ought to stop seeing each other.”

- “You’ve done good work for us, but we’re going to have to let you go.”

- “This paper has some good ideas, but I’m giving you a D grade because it is late.”

These “buts” often are a strategy for wrapping the speaker’s real but unpleasant message between nicer ideas in a psychological “sandwich”. This approach can be a face-saving strategy worth using at times. When the goal is to be absolutely clear; however, the most responsible approach is to deliver the positive and negative messages separately so they both get heard. It’s not always useful to “hide” negative feedback in a “but” sandwich!

Questions:

Some questions are sincere requests for information. Other questions, though, are use as a game, a way of making a statement without actually making the statement. “What are we having for dinner?” might hide the statement “I want to eat out” or “I want to get a pizza.”

- “How many textbooks are assigned in that class?” might hide the statement “I’m afraid to get into a class with too much reading.”

- “Are you doing anything tonight?” can be a less risky way of saying, “I want to go out with you tonight.”

- “Do you love me?” safely replaces the statement “I love you” which might be too embarrassing, too intimate, or too threatening to say directly.

Sometimes being indirect can be a tactful way to approach a topic that would be difficult to address head on. When used unnecessarily though, being indirect can be a way to avoid speaking for yourself.

“You” Language:

“I” language is a way of accepting responsibility for a message. In contrast, “you” language expresses a judgment of the other person. Positive judgments (“You look great today”) rarely cause problems, but notice how each of the following critical “you” statements implies that the subject of the complaint is doing something wrong.

- “You left this place a mess!”; “You didn’t keep your promise!”; “You are really crude sometimes!”

- Despite its name, “you” language doesn’t have to contain the pronoun you, which is often implied rather than stated outright.

- “That was a stupid joke!” (Your jokes are stupid)

- “Don’t be so critical!” (You’re too negative)

- “Mind your own business!” (You’re too nosy)

Whether the judgment is stated outright or implied, it’s easy to see why “you” language can arouse defensiveness. A “you” statement implies that the speaker is qualified to judge the target – not an idea that most listeners are willing to accept, even when the judgment is correct.

Fortunately, “I” language provides a more accurate and less provocative way to express a complaint. “I” language shows that the speaker takes responsibility for the complaint by describing his or her reaction to the other’s behavior without making any judgments about its worth.

Check out this video on “When you feel… I…. messages” and then read the description that follows. As always, see if you can spot your strengths and weak spots.

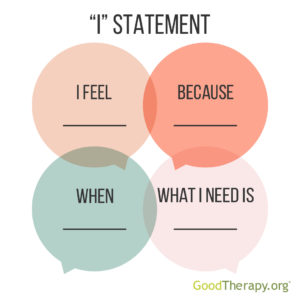

A complete “I” statement has 4 elements. It describes:

- the other person’s behavior

- your interpretations

- your feelings

- the consequences that the other person’s behavior has for you

These elements can appear in any order. A few examples of “I” statements illustrate how they sound in everyday conversation:

- “I get embarrassed (feeling) when you talk about my bad grades in front of our friends (behavior). I’m afraid they will think I’m stupid (interpretation). That’s why I got so worked up last night (consequence).”

- “When you didn’t pick me up on time this morning (behavior), I was late for class, and I wound up getting chewed out by the professor (consequences). It seemed to me

that my being on time didn’t seem important to you (interpretation) That’s why I got so mad (feeling).- “I haven’t been very affectionate (consequences) because you’ve hardly spent any time with me in the past few weeks (behavior). I’m not sure if you’re avoiding me, or if you’re just busy (interpretation). I’m confused (feeling) about how you feel about me, and I want to clear it up.”

When the risks of being misunderstood or getting a defensive reaction are high, it’s a good idea to include all four elements in your “I” message. In some cases, however, only one or two of them will get the job done:

- “I went to a lot of trouble fixing this dinner, and now it’s cold. Of course I’m mad!” (The behavior is obvious).

- “I’m worried because you haven’t called me up.” (“worried” is both a feeling and consequence.)

The role of emotion and genuineness

Even the best “I” statements won’t work unless it is delivered in the right way. If your words are nonjudgmental, but your tone of voice, facial expression, and posture all send “you” messages, a defensive response is likely to follow. The best way to make sure that your actions match your words is to remind yourself that your goal is to describe your thoughts, feelings, and wants and to explain how the other’s behavior affects you—not to act like a judge and jury.

Some readers have reservations about using “I” language even though it sounds like it would work. The best way to overcome questions about this communication skill is to answer them:

- “I get too angry to use “I” language.” It is true that when you’re angry the most likely reaction is to lash out with a judgmental “you” message. But it is probably smarter to keep quiet until you have thought about the consequences of what you might say than to blurt out something you will regret later. It is also important to note that there is plenty of room for expressing anger with “I” language. It is just that you own the feeling as yours (“You bet I’m mad at you!”) instead of distorting it into an attack (“That was a stupid thing to do!”)

- “Even with “I” language, the other person gets defensive.” Like every communication skill, “I” language will not always work. You might be so upset or irritated that your judgmental feelings contradict your words. Even if you deliver a perfectly worded “I” statement with total sincerity, the other person might be so defensive or un-cooperative that nothing you say will make matters better. But using “I” language will almost certainly improve your chances for success, with little risk that this approach will make matters worse.

- “’I’ language sounds artificial.” Because this is not the way we are accustomed to speaking, “I” language might feel awkward at first. As you become more used to making “I” statements they will sound more and more natural—and become more effective.

The more you practice using “I” language the less awkward you will feel. Using them in class and with your groups in a safe setting is the best place you will have for practice. Once you have grown in using the skill and gain more confidence you will be ready to tackle really challenging situations in a way that sounds natural and sincere.

“We” Language:

One way to avoid overuse of “I” language is to consider the pronoun we. “We” language implies that the issue is the concern and responsibility of both the speaker and receiver of a message. Consider these examples:

- “We need to figure out a budget that doesn’t bankrupt us.”

- “I think we have a problem. We cannot seem to talk about money without fighting.”

- “We are not doing a very good job of keeping the place clean, are we.”

It is easy to see how “we” language can help to build a constructive climate. It suggests a kind of “we are in this together” orientation that reflects the transactional nature of communication. People who use first- person plural pronouns signal their closeness, commonality, and cohesiveness with others. For example, couples who use “we” language are more satisfied than those who rely more heavily on “I” and “you” language.

On the other hand, “we” statements are not always appropriate. Sometimes using this pronoun sounds presumptuous because it suggests that you are speaking for the other person as well as yourself. It is easy to imagine someone responding to your statement “We have a problem…” by saying “Maybe you have a problem, but don’t tell me I do!”

Given the pros and cons of both “I” language and “we” language, what advice can we give about the most effective pronouns to use in interpersonal communication? Researchers have found that “I/we” combinations (for example, “I think that we…” or “I would like to see us…”) have a good chance of being received favorably. Because too much of any pronoun comes across as inappropriate, combining pronouns is generally good. If your “I” language reflects your position without being overly self-absorbed, your “you” language shows concern for others without judging them, and your “we” language includes others without speaking for them, you will probably come as close as possible to the ideal use of pronouns.

Check your cultural bias!

Although some of the recommendations above work across cultures, these criteria tend to reflect a very western style of communication in that they are direct and assertive. Keep in mind that providing and receiving feedback varies around the world. Be sure to not make assumptions about what will work. It’s helpful to be curious about other people’s communication styles and take this into consideration when providing feedback.

Read THIS to learn more about cross cultural communication styles.

Watch THIS VIDEO to listen to American and Chinese students talk openly about how their different communication styles and personalities create barriers to communication