Chapter Four: A Cultural Mosaic: Canada’s Multicultural Policy Then and Now

Abstract: This chapter focuses on the philosophical underpinnings of citizenship and belonging. It further explores how social work engages with immigration by embracing multiculturalism, rooted in liberalism (“respect for difference”)

Key concepts: Multiculturalism, monoculture, medical model, ‘professionalism’ and the stranger

Introduction

Countries of the Global South are constructed as not advanced in domains of the economy, politics and human rights. The story of the Global North depends on the belief that the lack of advancement has led to human rights abuses and other events, such as civil wars, rendering them as needing to be saved. At the same time, “needing to be saved” does not automatically translate to deserving. Individuals must be scrutinized to ensure the validity of their claims and the appropriate use of Canadian resources. This scrutiny contributes to the oversimplified idea that the Global South lacks economic advancement, education, opportunity, and safety, which pushes them out, and the Global North pulls people in with promises of a “better life.” Governments, organizations, and individuals position themselves as ‘helpers’ who move people and countries along the linear pathway of advancement. Terms such as ‘backwards’ and ‘uncivilized’ have been used to signal the starting point of modernity and civilization. This idea has one pinnacle or standard for success – capitalism, individualism, and a focus on human rights. Social work, as a profession, has been guilty of this imperial knowledge and pushing the modernity agenda (Carranza, 2021; Razack, 2009).

Despite the violent settler history that remains today (Blackstock, 2012), Canada has attempted to popularize a multicultural image of “protection and tolerance” for immigrants/forced migrants (Johnstone & Lee, 2020.p. 71). The image of ‘protection’ was built up by claims that Canada was a ‘safe’ destination for the underground railroad, draft dodgers, and those forcibly displaced (Johnstone & Lee, 2020; Carranza, 2017). Canada has claimed to be a ‘nation of immigrants’, arrogantly claiming worldliness and positive resettlement when reception is tolerant at best (Bhuyan et al., 2017, p. 17). The Canadian brand is crafted as a beacon of safety, hope and opportunity and has very publicly claimed to welcome large scale amounts of asylum seekers from El Salvador in the 1980s (Carranza et al., 2022), Syria in 2016 (Jeyapal, 2018) and at the time of this writing, those fleeing Afghanistan.

Social policies on immigration depend on understanding those arriving in Canada from the Global South as ‘the stranger/Other.’ As the stranger, knowledge, habits, customs and other non-Western ways of life are known and marked as different. The descendants of British and French settlers and other white countries are positioned as Canada’s natural inhabitants and citizens. The goal is to create an environment that encourages some (adopting Canadian social expectations) and demands (learning English or French) from others. Racialized immigrants/forced migrants the Global South are required to adapt, resettle and/or assimilate into the mainstream and dominant space which means, giving up markers of difference. This chapter explores how selective immigration advances nation-building and how Canada arrived at the official policies of multiculturalism. For Canada, multiculturalism is not just a policy approach. It is a national identity: difference is welcomed and celebrated here. What needs to be addressed is that there remains an idealized norm, mainstream or the dominant.

The landscape of multiculturalism is embedded in the Canadian psyche and a one-dimensional image of Canada as a ‘friendly’ nation of people that say ‘eh!’. However, strangeness is crucial in maintaining notions of Canadian-ness [white] as the norm and the ideal citizen. Building and relying on this image allows Canadians the capacity to shift and grow amidst an evolving world. They can be drivers of international business, peacekeepers, and innovators. Migration and arrival freeze the stranger as a stable identity – meaning those from the Global South are always ‘in need’ (of safety, economic security, or human rights), which Canada can provide. This discussion focuses on how multiculturalism hinges on the concept of ‘the Stranger’ (Ahmed, 2016).

Social policy is a regulatory force in Canada. Diving into the philosophical underpinnings of citizenship and belonging shows that social policy does not exist in a vacuum. Public discourse and opinion, along with economic policies and other considerations, play a dominating role in deciding which factors are brought to the political arena and who is chosen to represent them. Intertwined, public discourse and social policy shape who is and is not ‘deserving’ of legal and social citizenship. Further, policy determines which countries and citizens have met the threshold to be considered ‘in need of protection.’

The metamorphosis of policy into practice is not the focus; instead, it is how the policy environment shapes policymakers’ perceptions and how Canadians view it. Carrier and Sethi (2020) discuss the importance of challenging the divide between policy and practice to engage in social justice work. Sourcing the structural roots of oppression and marginalization can inform the work with individuals and communities by locating the context of their experience and direction for advocacy work (Carrier & Sethi, 2020). Values in policy are never neutral. These values were demonstrated by the violent dispossession of lands, enacted through policy when British settlers arrived in Canada (Lawrence, 2002). Jeyapal (2018) notes the importance of policy in immigration discourse as reproducing ongoing coloniality, maintained through instruments that are race(d), gendered and class-based. The examples include the points system, temporary foreign workers (targeted to farm workers from the Caribbean or Central America) and caregiver programs (often women from the Global South providing childcare). These mechanisms determine who can enter (legally), gets a pathway to citizenship, and can/cannot belong.

The profession’s history is intertwined with maintaining the structural roots of oppression and claims to social justice. Understanding immigrant/forced migrant reception and the role of ‘the stranger’ sets the stage for discussing how social work has worked within and against the projected image and actual practices of Canadian multiculturalism. As social work has many areas of practice, some of this engagement strengthened the image of ‘the stranger,’ while other efforts shifted the discourse to discuss the whiteness of Canada.

The ‘discourses of immigration‘ will refer to the policies about resettlement, those living the process, and how immigration is spoken about. An important note is that part of this discourse uses current and historical legal terminology such as ‘refugee,’ ‘newcomer,’ asylum seeker,’ or ‘immigrant’ to classify people within the migration process. It must be recognized that these terms impact how people are viewed and engaged with and in their own lived processes of migration and navigating belonging (Carranza, 2017).

Terminology also dictates access to services, identification, housing and work. For example, social service organizations provide supportive housing to refugee claimants for a time-limited period during their resettlement. Access to supportive or geared-to-income housing is more complex for other immigration categories, such as “Humanitarian and Compassionate ground” applications.

Immigration discourse in policy and public consciousness often recreates the colonial encounter in ways that frame Canada in an ‘us’ (safety and security) ‘them’ (violent and threatening) binary. Canada/ Canadians’ friendly ways are known and thought to be globally celebrated. Meanwhile, those migrating are considered foreign, defined by the stereotypes of their country. Usually underdeveloped and/or a geographically specific type of violence. One way ‘foreignness’ is codified in policy is the racialization process via categorizations of ‘visible minorities’ and blanket categorizations (i.e. South Asian). This racializing process is combined with how legal status defines immigrant/forced migrant belonging. It is vital to explore how the policy landscape shapes who is normalized, who can become a citizen, and, more importantly, a Canadian.

Jantzi (2014) contends that throughout history, Canada has sought to maintain a white European national identity. Building this identity required an ‘in’/desirable and an ‘out’/undesirable group that has been fluid, with some stable elements. One method was to manufacture the narrative of immigrants as, at minimum, not adhering to Canada’s ‘way of life’ and, at worst, a danger to public safety. This idea of pending dangers creates the need to securitize borders to maintain Canada as a safe haven – keeping violence out (Bannerji, 2000; Jantzi, 2015; Jeyapal, 2015). Constructing the colonial grid along the axis of belonging has been foundational to Canada’s colonial narrative (Carranza, 2016; Jeyapal, 2015). Exclusion is justified by the stories of ‘other’ countries, people, groups and identities, as dissimilar to ‘us’ and strange.

Markers of difference across policy, cultural, social and economic domains are known as strange, not welcome, threatening and dangerous (Ahmed, 2016). The definition of strange shifts, moving from violent, over-sexualized to terrorist and/or lazy, is rooted in geopolitical and historical realities.

According to Bannerji (2000), to maintain the hierarchy of race, Canada has cemented identities by establishing definitive differences on a ‘moral,’ ‘cultural,’ and ‘ethnic’ level. Culture is idealized as a group’s shared identity or identities based on shared traits, customs, values, norms, and behaviour patterns that are socially transmitted and highly influential in shaping individual and collective beliefs, experiences, and worldviews. However, culture is often limited to the one-dimensional characteristics of race and ethnicity shared by members of a specific group, which are often delineated into coded visual markers (Azzopardi & McNeill, 2016). Critiques of policies that hinge on culture as a marker of difference suggest that these perceptions ‘freeze’ those from the Global South in their constructed cultural traditions (Bannerji, 2000). Racialization and securitization conjoin in constructing and maintaining these constructions of the ‘foreign’ characteristics of immigrants and refugees from the Global South.

Welcome, or not, to Canada

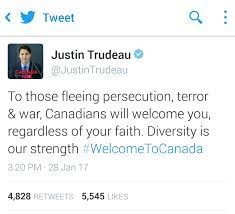

The 2016 image of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau with a family seeking asylum from Syria stating, “You are home now,” and the tweet, “To those fleeing persecution, terror & war, Canadians will welcome you, regardless of your faith. Diversity is our strength #WelcomeToCanada”

The 2016 image of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau with a family seeking asylum from Syria stating, “You are home now,” and the tweet, “To those fleeing persecution, terror & war, Canadians will welcome you, regardless of your faith. Diversity is our strength #WelcomeToCanada”

This rhetoric represents the warmth and acceptance of Canadian resettlement while blanketing the less-than-welcoming reality (Harding & Jeyapal, 2018). Migration has always had a place on the political agenda and is increasingly constrictive and militarized to keep people out. Opinion surveys may not be wholly representative of the Canadian public. However, opinion surveys indicate a discrepancy between abstractly held values and beliefs of multiculturalism and its practical application (Walker & Zuberi, 2019). What the data suggests, to a certain extent, is that Canada is not fully committed to multiculturalism in practice and not wholly accepting of racialized immigrants/forced migrants. This, too, is felt in the unactualized promises of migration for those who may not choose to be on the move (Walker & Zuberi, 2019).

Public discourse on immigration – the formal acceptance and informal belonging processes – occur along the colonial grid. The idealized white body (that conforms to Anglo norms) promoted for migration is not just unmarked by race. Canada has a long history of denying entry to people with disabilities/disabled people, Transmen and Transwomen and 2SLGBTQIA+ people. In immigration discourses, bodies are assigned worth. To be ‘of value,’ one must be aligned with gender and heteropatriarchal norms, healthy, and most importantly, productive in the capitalist economy. One example is the enforcement of policies that deny disabled people/people with disabilities entry to Canada, especially those coming from countries of the Global South (El-Yahib, 2015). To be considered desirable, one can advance the economy and can quickly adapt and ‘fit in.’ Whereas those who are racialized are constructed as needing time to ‘catch up.’ Catching up is a code for various resettlement tasks, from learning the language to re-establishing their profession. According to some, it also means doing the most to adopt ‘Canadian values’ (Walker & Zuberi, 2019). Migration streams have also ensured segments of the population are easily deportable – from temporary foreign workers whose status depends on their employer to those convicted of crimes. The following discusses some of Canada’s policy roots and public discourse that have led to the image of multiculturalism popularized today.

Policy roots of immigration. Immigration favoured white men, providing access to citizenship and belonging (Thobani, 2000). European White women were welcomed as wives and mothers. Racialized men were restricted to physical labour while being forced to assimilate in areas of language and customs. Women from “not preferred countries” were almost entirely excluded (Thobani, 2000). These early practices were connected to the ongoing colonial violence towards Indigenous people and attempts at erasure of any perceived ‘difference’ from whiteness. McLaren (1990) indicates this was termed ‘race betterment’ and the avoidance of ‘race suicide.’ Embedded in policy, immigration workers denied any persons deemed unlikely to assimilate (Henry et al., 1995). The framing of immigration has always been to meet the needs of those migrating – providing opportunities for moving up, safety and ‘a better life’. From its inception, immigration has been viewed as a process that must be controlled, with the thrust of resettlement being assimilative (Jakubowski, 1996). Looking back highlights how policies provided the foundation for the colonial grid in Canada. Initially, the goal was to create and maintain a white, Christian, monocultural identity in what would become the imagined community of Canada (Anderson, 2016; Carranza, 2021; Johnstone & Lee, 2020). Control did not end at the border. Nations, cities and even small towns were to build upon a shared identity of whiteness, Christianity and individualism.

Canada established itself as a nation-state by welcoming ‘preferred’ immigrants from Great Britain, the United States, France and some northern European nations over ‘non-preferred’ countries (Italy, Poland, Greece) or historically excluded groups (those from Japan, China, India and people who had been enslaved) (Bhuyan et al., 2017). Race and immigration are locked into capitalist expansion. Canada’s immigration and refugee policies are shaped by the economic needs within which they emerge (Simmons, 1992). In the first iterations of the Immigration Act of 1869, Canada claimed an “open door policy” with the goal of being a European farming country. The Act prevented “the landing of pauper or destitute immigrants” (Atkey, 1990, p. 59) and explicitly excluded those with disabilities, illness and people who had been convicted of a crime. Overt measures were spread through the Act to ensure that ‘undesirables’ were excluded on legal grounds (Jeyapal, 2018). These exclusions fueled Canada’s economic competitive edge. Migrants were considered a good fit, partly due to their adherence to the protestant work ethic and ability to advance Canada economically. Most importantly, their whiteness (Bhuyan et al., 2017). The insistence on British ‘stock’ and traditions was central to the (imagined) nationhood of Canada – codified in the “Nationality Preference System” (Simmons, 1990).

During economic expansion, immigration was broader applicants of workers and middle and upper-class applications. For example, during the late 1800s, when recruitment efforts failed to produce the large numbers of British and preferred nationalities required to settle the prairies, the boundaries of ‘desirable’ were expanded. The economic need expanded acceptance to include people from Ukraine, Italy and Poland (Jakubowski, 1996). In this iteration of policy and public imagination, white immigrants from previously excluded countries were labelled ‘superior stock.’ Superior stock was code for being apt to assimilate and be accepted (Elliot & Fleras, 1996, p.290).

The ‘white only’ clause in the Canadian Immigration Act gave the parliamentary cabinet the authority to prohibit any persons based on race or country of origin from coming to Canada (Johnstone, 2015). Prohibition was to avoid “their peculiar customs” and “an inability to become readily assimilated,” saturating Canadian public discourse. The fear was that if the difference was normalized, it would challenge what is and is not whiteness in Canada (Bhuyan et al., 2017, p. 67). In 1911, the government implemented a policy restricting Black people from the United States from coming to Canada, placing sanctions on any person or company assisting them. The word ‘race’ has strategically appeared and disappeared in legislation since its inception (Jakubowski, 1996). “Race” first emerged as a prohibitive/restrictive legal category in Section 38(c) of the Immigration Act of 1910 and amended in 1919 to include “nationality” (Hawkins, 1989, p. 17). Jakubowski (1996) identifies this inclusion as the first policy iteration of xenophobia.

When migration streams were needed to meet the needs of the workforce capacity, the urgency of the shortage overrode the desire for a monoculture. Recruitment began for expendable workers who could be exploited for manual and domestic labour. Beginning with those from China, migration included the $25 entry fee (sometimes more), known as the “Head Tax.” Canada collected $22 million from 1886-1923 (legislation abolished in 1947), preventing those without the financial means from migrating. Despite European migration dwindling, labour shortages and international pressure to accept humanitarian and refugee applications, this policy continued to prevent non-white immigration. However, it was edited to be preventative but in a more cloaked fashion (Irving et al., 1995).

Exceptions were made for ‘non-skilled labour,’ later deemed indentured. One example is those from Japan arriving to work on the TransCanada railroad. This form of labour remains today, with time-limited work programs like the Seasonal Agricultural Program or the Caregiver Program. People are tied to one employer and have limited to no benefits despite paying taxes and almost no pathway to citizenship. Productivity and participation in these programs depend on physical ability, and gender is targeted towards people from the Global South. Each program creates a category of migration that is easily expendable and can be revoked at any moment (Jeyapal, 2018).

The Canadian Pacific Railway became a significant driver of race in law and policy (Henry, 1995). The Chinese Immigration Act of 1922 (until 1947) prevented anyone from Asia from coming who did not respond to labour needs (Johnstone & Lee, 2020). During this time, over 15,000 labourers from Asian countries were admitted to build the railway. In public discourse, workers from China were marginally accepted because of the shortage and low-cost labour – but were heavily controlled in work and personal lives (Triadafilopoulos, 2007). Once the railroad was complete and workers were looking for new jobs, competition rose, and the ‘acceptance’ of racialized immigrants/forced migrants went drastically down (Jakubowski, 1996). Further, they were surveilled, housing restricted to certain areas and experienced racism in their daily lives (Triadafilopoulos, 2007).

These clauses were not the only ones. Before 1967, when the points system was implemented, numerous exclusionary race-based clauses existed. People from India and Pakistan were limited to 100-150 entries per year until 1962, and the “Gentleman’s Agreement” with Japan was limited to 400 people per year. The racist beliefs of Nazi Germany also fueled who was allowed entry, despite Canada’s fight against fascism. As Gaudet (2001) indicates, during the years when the Nazis were in power in Germany (and immediately afterwards), Canadian immigration policy was actively anti-Semitic. Canada’s record for accepting Jewish people fleeing the Holocaust is among the worst in the Western world. One official summed up Canadian policy towards Jewish asylum-seekers: “None is too many” (Gaudet, 2001).

An ‘out’ group mentality has been achieved through policy – based on race, geography, religion, and other shifting ‘undesirable’ characteristics. One example is in 2001, post 9/11 attacks in the United States, Canada reformed the Immigration Act to provide new powers to border and law officials to detain landed immigrants as security threats. In 2004, the method of arrival was further securitized, preventing refugee claims from those who arrived on a travel visa. By exclusion, the borders of the ‘in’ group are established around the degree of integrating visually, culturally and linguistically and follow the rules of the arrival and application process. This marks the ‘out’ group based on race, geography and other ‘non-preferred’ elements – defining their characteristics and re-making their strangeness while favouring the ‘in’ group (Thobani, 2000).

For asylum claims prior to WWI and WWII, Canada chose to keep the definition of a “migrant” ambiguous and delayed signing the UN Refugee Convention in 1951 (Sana, 2019). By prolonging signatory status, Canada did not have to adhere to Convention definitions and allowed the provision of temporary status for migrants – making people easily deportable. Signed in 1969, Canada was forced to broaden immigration from a nation-building and economic focus to one that included humanitarian efforts. Canada was now responsible for protecting migrants seeking refuge and asylum as a requirement of their signature (Bissett, 1986). The Convention simplified the definition of a refugee and clarified who was to be protected.

The post–World War era of the 1960s marked a decisive shift in Canada’s maintenance of an ‘out’ group from a legal and appearance standpoint. The global economy shifted, and the international focus was on human rights (Triadafilopoulos, 2007). Thobani (2000) noted that race exclusion became challenging to sustain for several reasons: the dismantling of colonial rule in formerly colonized countries of the Global South; scientific racism was losing ground due to the horrors of the Holocaust; the Civil Rights movement(s) in the U. S and around the world; and racialized people in Canada organizing against racist immigration discourses (p.17). According to Hawkins (1989), changing to a non-discriminatory policy approach did not promote an anti-racist Canada. Instead, to maintain status in the United Nations, which, without this adoption of policy, Canada’s interests would eventually be at odds. Claiming a non-discriminatory approach while controlling who can enter, the “Comprehensive Ranking Systems” (known as the points system) came into force in 1967 (Hawkins, 1989). The points system [in theory] determines eligibility for those who ‘choose’ or are not forcibly displaced to move to Canada, namely economic migrants. In 1971, in pursuit of making all Canadians feel valued, the government promoted the policy of multiculturalism to ensure cultural freedoms, break down stereotypes, and reduce discrimination. This policy drove forward an idea of equal but different, which came shortly after the race ‘preferred’ system was transformed into the universal points system (Nupur & Slade, 2011). For those seeking asylum, legislation has followed a different course.

The legal terminology for people seeking asylum in Canada has changed throughout legislation, including refugees and people applying on humanitarian and compassionate grounds. Canada previously had a framework related to human rights for defining which countries do and do not produce refugees, as seen in previous policy iterations of Designated Country of Origin (Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 2021). Increasingly, people are being forcibly displaced in ways that are not recognized in national policy and on the international stage – for example, climate change, gang-related violence, criminality and gender-based violence. However, each of these is related to colonization and ongoing coloniality globally. Immigration discourse in Canada – both policy and public opinion – has categorized refugees as ‘deserving’ and not deserving based on a range of factors such as nationality, ethnicity, race, country of origin, gender identities and sexuality. Deserving has meant that they are ‘worth’ safety and public funds. To be an ‘authentic’ refugee, one must be in dire need, vulnerable and without agency (Sana, 2019). This assessment is complex and lacks an understanding of how ‘refugee-producing countries’ are often previously colonized and continue to be exploited by the Global North. Canada’s immigration and resettlement system and public opinion often consider claimants “deserving/ needs to be saved” or trying to “abuse the Canadian system.”

Thobani (2000) notes that the language of non-discrimination in immigration policy, in theory, lives up to this goal. However, both the points system and the process of claiming asylum remain embedded in gendered and racist practices. Already having established the whiteness and Britishness of Canada, reforms to the Immigration Act (1976) sought to strengthen the “cultural and social fabric” and the “bilingual character of Canada.” (Thobani, 2000, p. 18). The Bilingual Commission of Canada ensured that policy dictated English and French as the national languages and cultures.

Immigration reforms cemented whiteness as Canada’s founding identity.

Asylum claims or applying for entrance into Canada are complicated and vary by originating country. Currently, people arriving in Canada or already in the country make an application to the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB) as Convention Refugees or Persons in Need of Protection.

Outside of Canada, under the Refugee and Humanitarian Resettlement Program, people are to use a referral program (by the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), a designated referral organization, or a private sponsorship group) to facilitate asylum claims. How refugee status is determined, the validity of asylum claims, and which countries are refugee-producing is a constantly shifting ground.

One way to see the connections between social policy and public discourse is in the Government of Canada’s (GoC) publications and gray literature. In these documents, “Most Canadians” is used to signify the public opinion of the majority and strategically attempts to build or appeal to a sense of collective values. For example, until 2019, Canada had a list of Designated Countries of Origin that“valued justice, protected human rights and did not produce refugees.” On the Immigration and Citizenship website, it states, “Most Canadians recognize that there are places in the world where it is less likely for a person to be persecuted compared to other areas. However, many people from these places try to claim asylum in Canada but are later found not to need protection. Too much time and too many resources are spent reviewing these unfounded claims” (GoC, 2017). These statements activate a sense of “what Canadians know” and “what Canadians want,” which is fiscal responsibility and the rejection of those potentially taking advantage. This list also highlights how Canada defines “in need of protection” vs the on-the-ground reality. For example, Mexico is no longer on the list in 2024, but in 2022, it had the highest number of refugee claims after Haiti (IRB, 2023).

The desire for some degree of heterogeneity remains today in the imagined community of Canada. With some differences tolerated, fashion and food are examples, but the essential pieces must change. ‘Catching up’ is often related to assimilating into ways of life in Canada and reinforces the colonial relationship – those from the Global North are more “advanced.” One such example is how education and professions from the Global North can be easily transferred while restricting countries of the Global South. Credentials are deemed not good enough, and people need to upgrade or catch up their skills to the level of modern countries (Sakamoto, 2017). There is also a requirement for ‘Canadian Experience’ in applications. Applicants who are not applying for humanitarian, compassion or refuge are assessed and receive points for education, language and work history – the more points, the increased chance of acceptance (Citizenship and Immigration, 2020). ‘Canadian experience’ eases the transition into the economy where people can gain employment quicker. Obtaining ‘Canadian experience’ is complex; one must have a previous work history that aligns with Canada’s – transferrable skills and/or education that is considered on par (Bhuyan et al., 2017). Acquiring this experience is a qualifier to determine who can achieve economic and social integration – and who can pay for their resettlement.

Producing a Multicultural Canada

The Multiculturalism policy (1988) codified these principles in legislation and took the goals of equity one step further. The intention was for all Canadians to see themselves represented. In this way, Canadian culture would remain a fundamental way of life that, at minimum, was expected to tolerate and respect ‘difference.’ Various slogans of ‘different but equal’ were activated to encourage everyone to work towards equality in all aspects of life (Kymlicka, 2004). Diversity and equality were considered the foundation of multiculturalism, with intercultural sharing, equity and inclusion as

essential elements (Berry, 2013). At the start of the policy, maintaining diversity was the focus, with an intentional shift away from assimilation. According to Berry (2013), sharing and social inclusion have been pathways to promoting equality and equity. A focus on Canadian citizenship, or ‘we are all one country’, has dominated policy goals in the 1990s. Multiculturalism and its policies reflect how the nation imagines resettlement and ‘old stock Canadians’ to respond (Carranza, 2017).

Resettlement is idealized as a form of social inclusion, acceptance, and maintaining pre-migration identity in a nation where diverse identities are celebrated as integral to the whole – a multicultural mosaic (Walker & Zuberi, 2019).

In 1998, the Washington Post reported:

In contrast to the melting pot metaphor of Europe and the United States, Canada uses the image of the mosaic — brightly coloured bits of ethnicity, culture, racial identity and language embedded side by side. They may contrast with one another, but together, they form a portrait of the nation in the same way the dots on a pointillist painting convey a coherent image. Increasingly, though, this nation of immigrants — once overwhelmingly white, now multihued — has begun to confront a troubling question: With all these differences, does being Canadian still mean anything more than sharing a vast, cold expanse of land? (Schneider, 1998)

This image of the multicultural mosaic influences Canada’s role on the international stage. Policies, rhetoric and images support the Canadian brand in the eyes of the world and secure, powerful positions at international tables, such as the United Nations (Nytagodien & Neal, 2004). Canada has been viewed as ‘exceptional’ in accepting large numbers of refugees (Bhuyan et al., 2017).

However, these policies construct immigrants/forced migrants as both racialized and foreign, legally and formally, and maintain this marking, ranging from employment documents (disclosing status) to the census (Jeyapal, 2018). Immigration and social policy play significant roles in defining who can belong and where and have a racializing function within institutions.

Critiques of this policy indicate that the ‘cultural’ portion came to dominate the entire discourse. From a policy-to-practice perspective, critiques of multiculturalism suggest that people actively maintaining their history and heritage will ultimately create a sense of division and prevent a feeling of a unifying national identity among all Canadians (Berry, 2013; Nylund, 2011). Under this approach, multiculturalism equates ‘difference,’ especially racialization, to a ‘way of life’ (Ahmed, 2016). This ‘way’ of living and being in the world is distinctly not Canadian and not white. It draws false equations from race to ethnicity and code difference as ‘culture.’ Criticism suggests that there can be too much focus on difference (‘respect for diversity’), which undermines sameness, national unity, and identity. Other approaches, such as the melting pot in the U.S., blur the lines between the country of origin identity and that of the country of settlement to maintain the foci of being “American” (Berry, 2005). Whilst both approaches have their downfalls, critical race scholars have critiqued multiculturalism for focusing on difference in a way that renders whiteness invisible as a race (McLaren, 1994). The outcome of this attempt at invisibilization is naturalization, where whiteness becomes the norm and standard for identity.

Critics have also indicated that this approach to celebrating diversity stops at food, dress and dance, rendering political and structural contributions by immigrants/forced migrants invisible (Jantiz, 2014). People are encouraged to be tolerant and accepting of difference – to a point. A Canadian opinion poll in 2016 conducted by Angus Ried and the BBC found that 2/3 of respondents believe immigrants/forced migrants should “do more to fit in”. In another question, 1/3 of respondents were dissatisfied with how people were integrating in their cities. Public opinion shapes the degree to which tolerance develops on individual and collective levels, contributing to policy discourse (Jeyapal, 2018). The guidelines for tolerance and who can be marginalized are constantly shifting. These community tolerances have circular impacts from individual to national levels.

The undeniable fallacy of multiculturalism and its policies is that Canada was founded upon the decimation of Indigenous peoples, their relationship to the land, their communities and their ways of life. The goal of colonization, codified in the Indian Act (1876), was to create a white European identity with British and French settlers (Blackstock, 2012). Johnstone and Lee (2020) identified that knowledge of this history, including residential schools – the last one closing within the last three decades (1991) was minimal among Canadians. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2015 when more Canadians became aware of this history (Truth and Reconciliation Report, 2016). This short synopsis acknowledges the violence upon which Multiculturalism and what it erases was built and encourages further reading. Despite Canada favouring the mosaic/multicultural approach where people keep their heritage – cultures are remade as unknown and therefore ‘strange.’ ‘Catching up’ represents the idea of the Global North, formerly the ‘First World,’ as exemplifying notions of modernity, progress and development. The other countries of the Global North are known to each other, and therefore, not much change is expected. Often English-speaking or bilingual, they have similar foods and customs and, if not, can be adapted – such as perogies!

Immigration has many intersecting domains: legal, social, economic and political sectors, each impacting the other. Belonging speaks to acceptance in the legal sense but also has ties in the social and day-to-day realms. For example, who is expected to be in spaces such as parent-teacher associations, golf clubs, and other professions? Who is considered to be a leader? Can they be racialized? Can they be female? Have an accent? As social workers whose ethical oaths include fostering diversity and multiculturalism, it is critical to reflect on our own and other’s perceptions of belonging and the embedded assumptions in our psyches. How multiculturalism is practiced daily, in organizations is idealized as challenging the embedded privilege and whiteness in the constructions of difference (Johnstone & Lee, 2020).

- How and why does Canada promote its Multicultural identity?

- In what ways do immigration ideologies and policy services favour assimilation?

- In what ways does social work promote multiculturalism?

Feedback/Errata