Chapter 2. Sociological Research

Learning Objectives

2.1. Approaches to Sociological Research

- Define and describe the scientific method.

- Explain how the scientific method is used in sociological research.

- Understand the difference between positivist and interpretive approaches to the scientific method in sociology.

- Define what reliability and validity mean in a research study.

- Differentiate between four kinds of research methods: surveys, experiments, field research, and secondary data or textual analysis.

- Understand why certain topics are better suited to different research approaches.

- Understand why ethical standards exist.

- Demonstrate awareness of the Canadian Sociological Association’s Code of Ethics.

- Define value neutrality, and outline some of the issues of value neutrality in sociology.

Introduction to Sociological Research

In an unfortunate comment following the Boston Marathon bombing in April 2013, the then Prime Minister Stephen Harper said “this is not a time to commit sociology.” He implied that the “utter condemnation of this kind of violence” precluded drawing on sociological research into the causes of political violence (Cohen, 2013). In his [Harper’s] position, there is a disjunction between taking a strong political and moral stance on violence on one hand and working towards a deeper, evidence-based understanding of the social causes of acts of violence on the other. Behind the political and moral rhetoric of Stephen Harper’s statement are a number of densely solidified beliefs about the nature of a “terrorist” individual — “people who have agendas of violence that are deep and abiding, [who] are a threat to all the values that our society stands for” (Cohen, 2013). In this framework, the terrorist is a kind of person who is beyond reason and morality. Therefore, sociological analysis is not only futile in the former Prime Minister’s opinion but also, for the same reasons, contrary to the “utter determination through our laws and through our activities to do everything we can to prevent and counter [terrorist violence]” (Cohen, 2013).

However, in the research of Robert Pape (2005) a different picture of the terrorist emerges. In the case of the 462 suicide bombers Pape studied, not only were the suicide bombers relatively well educated and affluent, but as other studies of suicide bombers in general confirm, they were not mentally imbalanced per se, not blindly motivated by religious zeal, and not unaffected by the moral ambivalence of their proposed acts. They were ordinary individuals caught up in extraordinary circumstances. How would this understanding of the terrorist individual affect the drafting of public policy and public responses to terrorism?

Sociological research is especially important with respect to public policy debates. The political controversies that surround the question of how best to respond to terrorism and violent crime are difficult to resolve at the level of political rhetoric. Often, in the news and in public discourse, the issue is framed in moral terms and therefore, for example, the policy alternatives get narrowed to the option of either being “tough” or “soft” on crime. Tough and soft are moral categories that reflect a moral characterization of the issue. A question framed by these types of moral categories cannot be resolved using evidence-based procedures. Posing the debate in these terms narrows the range of options available and undermines the ability to raise questions about what responses to crime actually work.

In fact policy debates over terrorism and crime seem especially susceptible to the various forms of specious, unscientific reasoning described later in this chapter. The story of the isolated individual, whose specific act of violence becomes the basis for the belief that the criminal justice system as a whole has failed, illustrates several qualities of unscientific thinking: knowledge based on casual observation, knowledge based on over-generalization, and knowledge based on selective evidence. The sociological approach to policy questions is essentially different since it focuses on examining the effectiveness of different social control strategies for addressing different types of violent behaviour and the different types of risk to public safety. Thus, from a sociological point of view, it is crucial to think systematically about who commits violent acts and why.

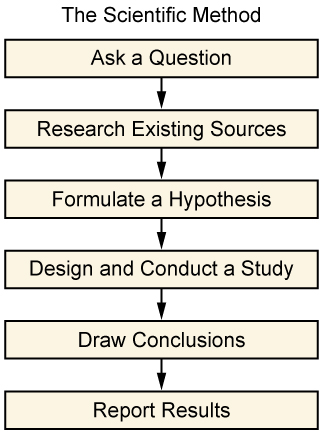

Although moral claims and opinions are of interest to sociologists, sociological researchers use empirical evidence (that is, evidence corroborated by direct experience and/or observation) combined with the scientific method to deliver sound sociological research. A truly scientific sociological study of the social causes that lead to terrorist or criminal violence would involve a sequence of prescribed steps: defining a specific research question that can be answered through empirical observation; gathering information and resources through detailed observation; forming a hypothesis; testing the hypothesis in a reproducible manner; analyzing and drawing conclusions from the data; publishing the results; and anticipating further development when future researchers respond to and re-examine the findings.

An appropriate starting point in this case might be the question “What are the social conditions of individuals who are drawn to commit terrorist acts?” In a casual discussion of the issue, or in the back and forth of Twitter or news comment forums, people often make arguments based on their personal observations and insights, believing them to be accurate. But the results of casual observation are limited by the fact that there is no standardization—who is to say if one person’s observation of an event is any more accurate than another’s? To mediate these concerns, sociologists rely on systematic research processes.

The unwillingness to “commit sociology” and think more deeply about the roots of political violence might lead to a certain moral or rhetorical image of an “uncompromising” response to the “terrorist threat,” but not a response that has proven effective in practice nor one that exhausts the options for preventing and countering acts of political violence. Contrary to the former Prime Minister’s statements, the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombing is precisely a moment to commit sociology if the issues that produce acts of violence are to be addressed.

2.1. Approaches to Sociological Research

When sociologists apply the sociological perspective and begin to ask questions, no topic is off limits. Every aspect of human behaviour is a source of possible investigation. Sociologists question the world that humans have created and live in. They notice patterns of behaviour as people move through the world. Using sociological methods and systematic research within the framework of the scientific method, sociologists have discovered workplace patterns that have transformed industries, family patterns that have enlightened parents, and education patterns that have aided structural changes in classrooms.

Depending on the focus and the type of research conducted, sociological findings could be useful in addressing any of the three basic interests or purposes of sociological knowledge we discussed in the last chapter: the positivist interest in quantitative factual evidence to determine effective social policy decisions, the interpretive interest in understanding the meanings of human behaviour to foster mutual understanding and consensus, and the critical interest in knowledge useful for challenging power relations and emancipating people from conditions of servitude. It might seem strange to use scientific practices to study social phenomena but, as we have argued above, it is extremely helpful to rely on systematic approaches that research methods provide.

Sociologists often begin the research process by asking a question about how or why things happen. It might be a unique question about a new trend or an old question about a common aspect of life. Once a question is formed, a sociologist proceeds through an in-depth process to answer it. Depending on the nature of the topic and the goals of the research, sociologists have a variety of methodologies to choose from. In particular, in deciding how to design that process, the researcher may adopt a positivist methodology or an interpretive methodology. Both types of methodology can be useful for critical research strategies. The following sections describe these approaches to acquiring knowledge.

Science vs. Non-Science

We live in an interesting time in which the certitudes and authority of science are frequently challenged. In the natural sciences, people doubt scientific claims about climate change and the safety of vaccines. In the social sciences, people doubt scientific claims about the declining rate of violent crime or the effectiveness of needle exchange programs. Sometimes there is a good reason to be skeptical about science, when scientific technologies prove to have adverse effects on the environment, for example; sometimes skepticism has dangerous outcomes, when epidemics of diseases like measles suddenly break-out in schools due to low vaccination rates. In fact, skepticism is central to both natural and social sciences, but from a scientific point of view the skeptical attitude needs to be combined with systematic research in order for knowledge to move forward.

In sociology, science provides the basis for being able to distinguish between everyday opinions or beliefs and propositions that can be sustained by evidence. In his paper The Normative Structure of Science (1942/1973) the sociologist Robert Merton argued that science is a type of empirical knowledge organized around four key principles, often referred to by the acronym CUDOS:

- Communalism: The results of science must be made available to the public; science is freely available, shared knowledge open to public discussion and debate.

- Universalism: The results of science must be evaluated based on universal criteria, not parochial criteria specific to the researchers themselves.

- Disinterestness: Science must not be pursued for private interests or personal reward.

- Organized Skepticism: The scientist must abandon all prior intellectual commitments, critically evaluate claims, and postpone conclusions until sufficient evidence has been presented; scientific knowledge is provisional.

For Merton, therefore, non-scientific knowledge is knowledge that fails in various respects to meet these criteria. Types of esoteric or mystical knowledge, for example, might be valid for someone on a spiritual path, but because this knowledge is passed from teacher to student and it is not available to the public for open debate, or because the validity of this knowledge might be specific to the individual’s unique spiritual configuration, esoteric or mystical knowledge is not scientific per se. Claims that are presented to persuade (rhetoric), to achieve political goals (propaganda, of various sorts), or to make profits (advertising) are not scientific because these claims are structured to satisfy private interests. Propositions which fail to stand up to rigorous and systematic standards of evaluation are not scientific because they can not withstand the criteria of organized skepticism and scientific method.

The basic distinction between scientific and common, non-scientific claims about the world is that in science “seeing is believing” whereas in everyday life “believing is seeing” (Brym, Roberts, Lie, & Rytina, 2013). Science is in crucial respects based on systematic observation following the principles of CUDOS. Only on the basis of observation (or “seeing”) can a scientist believe that a proposition about the nature of the world is correct. Research methodologies are designed to reduce the chance that conclusions will be based on error. In everyday life, the order is typically reversed. People “see” what they already expect to see or what they already believe to be true. Prior intellectual commitments or biases predetermine what people observe and the conclusions they draw.

Many people know things about the social world without having a background in sociology. Sometimes their knowledge is valid; sometimes it is not. It is important, therefore, to think about how people know what they know, and compare it to the scientific way of knowing. Four types of non-scientific reasoning are common in everyday life: knowledge based on casual observation, knowledge based on selective evidence, knowledge based on overgeneralization, and knowledge based on authority or tradition.

| Way of Knowing | Description |

|---|---|

| Casual Observation | Occurs when we make observations without any systematic process for observing or assessing the accuracy of what we observed. |

| Selective Observation | Occurs when we see only those patterns that we want to see, or when we assume that only the patterns we have experienced directly exist. |

| Overgeneralization | Occurs when we assume that broad patterns exist even when our observations have been limited. |

| Authority/Tradition | A socially defined source of knowledge that might shape our beliefs about what is true and what is not true. |

| Scientific Research Methods | An organized, logical way of learning and knowing about our social world. |

Many people know things simply because they have experienced them directly. If you grew up in Manitoba you may have observed what plenty of kids learn each winter, that it really is true that one’s tongue will stick to metal when it’s very cold outside. Direct experience may get us accurate information, but only if we are lucky. Unlike the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, in general we are not very careful observers. In this example, the observation process is not really deliberate or formal. Instead, you would come to know what you believe to be true through casual observation. The problem with casual observation is that sometimes it is right, and sometimes it is wrong. Without any systematic process for observing or assessing the accuracy of our observations, we can never really be sure if our informal observations are accurate.

Many people know things because they overlook disconfirming evidence. Suppose a friend of yours declared that all men are liars shortly after she had learned that her boyfriend had deceived her. The fact that one man happened to lie to her in one instance came to represent a quality inherent in all men. But do all men really lie all the time? Probably not. If you prompted your friend to think more broadly about her experiences with men, she would probably acknowledge that she knew many men who, to her knowledge, had never lied to her and that even her boyfriend did not generally make a habit of lying. This friend committed what social scientists refer to as selective observation by noticing only the pattern that she wanted to find at the time. She ignored disconfirming evidence. If, on the other hand, your friend’s experience with her boyfriend had been her only experience with any man, then she would have been committing what social scientists refer to as overgeneralization, assuming that broad patterns exist based on very limited observations.

Another way that people claim to know what they know is by looking to what they have always known to be true. There is an urban legend about a woman who for years used to cut both ends off of a ham before putting it in the oven (Mikkelson, 2005). She baked ham that way because that is the way her mother did it, so clearly that was the way it was supposed to be done. Her knowledge was based on a family tradition (traditional knowledge). After years of tossing cuts of perfectly good ham into the trash, however, she learned that the only reason her mother cut the ends off ham before cooking it was that she did not have a pan large enough to accommodate the ham without trimming it.

Without questioning what we think we know is true, we may wind up believing things that are actually false. This is most likely to occur when an authority tells us that something is true (authoritatve knowledge). Our mothers are not the only possible authorities we might rely on as sources of knowledge. Other common authorities we might rely on in this way are the government, our schools and teachers, and churches and ministers. Although it is understandable that someone might believe something to be true if someone he or she looks up to or respects has said it is so, this way of knowing differs from the sociological way of knowing. Whether quantitative, qualitative, or critical in orientation, sociological research is based on the scientific method.

The Scientific Method

Sociologists make use of tried-and-true methods of research, such as experiments, surveys, field research, and textual analysis. But humans and their social interactions are so diverse that they can seem impossible to chart or explain. It might seem that science is about discoveries and chemical reactions or about proving hypotheses about elementary particles right or wrong rather than about exploring the nuances of human behaviour. However, this is exactly why scientific models work for studying human behaviour. A scientific process of research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results. This is the case for both positivist quantitative methodologies, which seek to translate observable phenomena into unambiguous numerical data, and interpretive qualitative methodologies, which seek to translate observable phenomena into definable units of meaning. The social scientific method in both cases involves developing and testing theories about the world based on empirical (i.e., observable) evidence. The social scientific method is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the social world, and it strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical. It involves a series of established steps known as the research cycle.

However, just because sociological studies use the scientific method it does not make the results less human. Sociological topics like the causes and conditions of political violence are typically not amenable to the mathematical precision or quantifiable predictions of physics or chemistry. In the field of sociology, results of studies tend to provide people with access to knowledge they did not have before — knowledge of people’s social conditions, knowledge of rituals and beliefs, knowledge of trends and attitudes. Nevertheless, no matter what research approach is used, researchers want to maximize the study’s reliability (how likely research results are to be replicated if the study is reproduced). Reliability increases the likelihood that what is true of one person will be true of all people in a group. Researchers also want to maximize the study’s validity (how well the study measures what it was designed to measure).

A subtopic in the field of political violence would be to examine the sources of homegrown radicalization: What are the conditions under which individuals in Canada move from a state of indifference or moderate concern with political issues to a state in which they are prepared to use violence to pursue political goals? The reliability of a study of radicalization reflects how well the social factors unearthed by the research represent the actual experience of political radicals. Validity ensures that the study’s design accurately examined what it was designed to study. An exploration of an individual’s propensity to plan or engage in violent acts or to go abroad to join a terrorist organization should address those issues and not confuse them with other themes such as why an individual adopts a particular faith or espouses radical political views. As research from the UK and United States has in fact shown, while jihadi terrorists typically identify with an Islamic world view, a well-developed Islamic identity counteracts jihadism. Similarly, research has shown that while it intuitively makes sense that people with radical views would adopt radical means like violence to achieve them, there is in fact no consistent homegrown terrorist profile, meaning that it is not possible to predict whether someone who espouses radical views will move on to committing violent acts (Patel, 2011). To ensure validity, research on political violence should focus on individuals who engage in political violence.

Sociologists use the scientific method not only to collect but to interpret and analyze the data. They deliberately apply scientific logic and objectivity. They are interested in but not attached to the results. Their research work is independent of their own political or social beliefs. This does not mean researchers are not critical. Nor does it mean they do not have their own personalities, preferences, and opinions. But sociologists deliberately use the scientific method to maintain as much objectivity, focus, and consistency as possible in a particular study. With its systematic approach, the scientific method has proven useful in shaping sociological studies. The scientific method provides a systematic, organized series of steps that help ensure objectivity and consistency in exploring a social problem. These steps provide the means for accuracy, reliability, and validity. In the end, the scientific method provides a shared basis for discussion and analysis (Merton, 1949/1968). Typically, the scientific method starts with these steps, which are described below: 1) ask a question; 2) research existing sources; and 3) formulate a hypothesis.

Ask a Question

The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geography and time frame. “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?” would be too vague. The question should also be broad enough to have universal merit. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” would be too narrow. That said, happiness and hygiene are worthy topics to study.

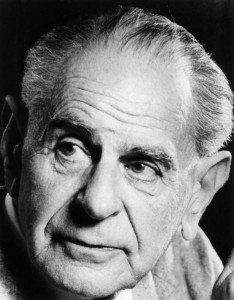

Sociologists do not rule out any topic, but would strive to frame these questions in better research terms. That is why sociologists are careful to define their terms. Karl Popper (1902-1994) described the formulation of scientific propositions in terms of the concept of falsifiability (1963). He argued that the key demarcation between scientific and non-scientific propositions was not ultimately their truth, nor their empirical verification, but whether or not they were stated in such a way as to be falsifiable; that is, whether a possible empirical observation could prove them wrong. If one claimed that evil spirits were the source of criminal behaviour, this would not be a scientific proposition because there is no possible way to definitively disprove it. Evil spirits cannot be observed. However, if one claimed that higher unemployment rates are the source of higher crime rates, this would be a scientific proposition because it is theoretically possible to find an instance where unemployment rates were not correlated to crime rates. As Popper said, “statements or systems of statements, in order to be ranked as scientific, must be capable of conflicting with possible, or conceivable, observations” (1963).

Once a proposition is formulated in a way that would permit it to be falsified, the variables to be observed need to be operationalized. In a hygiene study, for instance, hygiene could be defined as “personal habits to maintain physical appearance (as opposed to health),” and a researcher might ask, “How do differing personal hygiene habits reflect the cultural value placed on appearance?” When forming these basic research questions, sociologists develop an operational definition; that is, they define the concept in terms of the physical or concrete steps it takes to objectively measure it. The concept is translated into an observable variable, a measure that has different values. The operational definition identifies an observable condition of the concept.

By operationalizing a variable of the concept, all researchers can collect data in a systematic or replicable manner. The operational definition must be valid in the sense that it is an appropriate and meaningful measure of the concept being studied. It must also be reliable, meaning that results will be close to uniform when tested on more than one person. For example, good drivers might be defined in many ways: Those who use their turn signals; those who do not speed; or those who courteously allow others to merge. But these driving behaviours could be interpreted differently by different researchers, so they could be difficult to measure. Alternatively, “a driver who has never received a traffic violation” is a specific description that will lead researchers to obtain the same information, so it is an effective operational definition. Asking the question, “how many traffic violations has a driver received?” turns the concepts of “good drivers” and “bad drivers” into variables which might be measured by the number of traffic violations a driver has received. Of course the sociologist has to be wary of the way the variables are operationalized. In this example we know that black drivers are subject to much higher levels of police scrutiny than white drivers, so the number of traffic violations a driver has received might reflect less on their driving ability and more on the crime of “driving while black.”

Research Existing Sources

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review, which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to a university library and a thorough online search will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted on the topic at hand and enables them to position their own research to build on prior knowledge. It allows them to sharpen the focus of their research question and avoid duplicating previous research. Researchers — including student researchers — are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or sources that inform their work. While it is fine to build on previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly and never plagiarized. To study hygiene and its value in a particular society, a researcher might sort through existing research and unearth studies about childrearing, vanity, obsessive-compulsive behaviours, and cultural attitudes toward beauty. It is important to sift through this information and determine what is relevant. Using existing sources educates a researcher and helps refine and improve a study’s design.

Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an assumption about how two or more variables are related; it makes a conjectural statement about the relationship between those variables. It is an educated guess because it is not random but based on theory, observations, patterns of experience, or the existing literature. The hypothesis formulates this guess in the form of a testable proposition. However, how the hypothesis is handled differs between the positivist and interpretive approaches. Positivist methodologies are often referred to as hypothetico-deductive methodologies. A hypothesis is derived from a theoretical proposition. On the basis of the hypothesis a prediction or generalization is logically deduced. In positivist sociology, the hypothesis predicts how one form of human behaviour influences another. How does being a black driver affect the number of times the police will pull you over?

Successful prediction will determine the adequacy of the hypothesis and thereby test the theoretical proposition. Typically positivist approaches operationalize variables as quantitative data; that is, by translating a social phenomenon like health into a quantifiable or numerically measurable variable like “number of visits to the hospital.” This permits sociologists to formulate their predictions using mathematical language like regression formulas to present research findings in graphs and tables, and to perform mathematical or statistical techniques to demonstrate the validity of relationships.

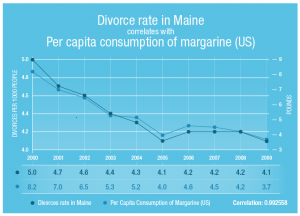

Variables are examined to see if there is a correlation between them. When a change in one variable coincides with a change in another variable there is a correlation. This does not necessarily indicate that changes in one variable causes a change in another variable, however; just that they are associated. A key distinction here is between independent and dependent variables. In research, independent variables are the cause of the change. The dependent variable is the effect, or thing that is changed. For example, in a basic study, the researcher would establish one form of human behaviour as the independent variable and observe the influence it has on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by level of education (the independent variable)?

For it to become possible to speak about causation, three criteria must be satisfied:

- There must be a relationship or correlation between the independent and dependent variables.

- The independent variable must be prior to the dependent variable.

- There must be no other intervening variable responsible for the causal relationship.

It is important to note that while there has to be a correlation between variables for there to be a causal relationship, correlation does not necessarily imply causation. The relationship between variables can be the product of a third intervening variable that is independently related to both. For example, there might be a positive relationship between wearing bikinis and eating ice cream, but wearing bikinis does not cause eating ice cream. It is more likely that the heat of summertime causes both an increase in bikini wearing and an increase in the consumption of ice cream.

The distinction between causation and correlation can have significant consequences. For example, Aboriginal Canadians are overrepresented in prisons and arrest statistics. As we noted in Chapter 1, in 2013 Aboriginal people accounted for about 4 percent of the Canadian population, but they made up 23.2 percent of the federal penitentiary population (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2013). There is a positive correlation between being an Aboriginal person in Canada and being in jail. Is this because Aboriginal people are racially or biologically predisposed to crime? No. In fact there are at least four intervening variables that explain the higher incarceration of Aboriginal people (Hartnagel, 2004): Aboriginal people are disproportionately poor and poverty is associated with higher arrest and incarceration rates; Aboriginal lawbreakers tend to commit more detectable “street” crimes than the less detectable “white collar” crimes of other segments of the population; the criminal justice system disproportionately profiles and discriminates against Aboriginal people; and the legacy of colonization has disrupted and weakened traditional sources of social control in Aboriginal communities.

| Hypothesis | Variable | Dependent Variable |

|---|---|---|

| The greater the availability of affordable housing, the lower the homeless rate. | Affordable Housing | Homeless Rate |

| The greater the availability of math tutoring, the higher the math grades. | Math Tutoring | Math Grades |

| The greater the police patrol presence, the safer the neighbourhood. | Police Patrol Presence | Safer Neighbourhood |

| The greater the factory lighting, the higher the productivity. | Factory Lighting | Productivity |

| The greater the amount of public auditing, the lower the amount of political dishonesty. | Auditing | Political Dishonesty |

At this point, a researcher’s operational definitions help measure the variables. In a study asking how tutoring improves grades, for instance, one researcher might define “good” grades as a C or better, while another uses a B+ as a starting point for good. Another operational definition might describe “tutoring” as “one-on-one assistance by an expert in the field, hired by an educational institution.” Those definitions set limits and establish cut-off points, ensuring consistency and replicability in a study. As the chart shows, an independent variable is the one that causes a dependent variable to change. For example, a researcher might hypothesize that teaching children proper hygiene (the independent variable) will boost their sense of self-esteem (the dependent variable). Or rephrased, a child’s sense of self-esteem depends, in part, on the quality and availability of hygienic resources.

Of course, this hypothesis can also work the other way around. Perhaps a sociologist believes that increasing a child’s sense of self-esteem (the independent variable) will automatically increase or improve habits of hygiene (now the dependent variable). Identifying the independent and dependent variables is very important. As the hygiene example shows, simply identifying two topics, or variables, is not enough: Their prospective relationship must be part of the hypothesis. Just because a sociologist forms an educated prediction of a study’s outcome doesn’t mean data contradicting the hypothesis are not welcome. Sociologists analyze general patterns in response to a study, but they are equally interested in exceptions to patterns.

In a study of education, a researcher might predict that high school dropouts have a hard time finding a rewarding career. While it has become at least a cultural assumption that the higher the education, the higher the salary and degree of career happiness, there are certainly exceptions. People with little education have had stunning careers, and people with advanced degrees have had trouble finding work. A sociologist prepares a hypothesis knowing that results will vary.

Hypothesis Formation in Qualitative Research

While many sociologists rely on the positivist hypothetico-deductive method in their research, others operate from an interpretive approach. While still systematic, this approach typically does not follow the hypothesis-testing model that seeks to make generalizable predictions from quantitative variables. Instead, an interpretive framework seeks to understand social worlds from the point of view of participants, leading to in-depth knowledge. It focuses on qualitative data, or the meanings that guide people’s behaviour. Rather than relying on quantitative instruments, like fixed questionnaires or experiments, which can be artificial, the interpretive approach attempts to find ways to get closer to the informants’ lived experience and perceptions.

Interpretive research is generally more descriptive or narrative in its findings than positivist research. It can begin from a deductive approach by deriving a hypothesis from theory and then seeking to confirm it through methodologies like in-depth interviews. However, it is ideally suited to an inductive approach in which the hypothesis emerges only after a substantial period of direct observation or interaction with subjects. This type of approach is exploratory in that the researcher also learns as he or she proceeds, sometimes adjusting the research methods or processes midway to respond to new insights and findings as they evolve.

For example, Glaser and Strauss’ (1967) classic elaboration of grounded theory proposed that qualitative researchers working with rich sources of qualitative data from interviews or ethnographic observations need to go through several stages of coding the data before a strong theory of the social phenomenon under investigation can emerge. In the initial stage, the researcher is simply trying to categorize and sort the data. The researchers do not predetermine what the relevant categories of the social experience are but analyze carefully what their subjects actually say. For example, what are the working definitions of health and illness that hospital patients use to describe their situation? In the first stage, the researcher tries to label the common themes emerging from the data: different ways of describing health and illness. In the second stage, the researcher takes a more analytical approach by organizing the data into a few key themes: perhaps the key assumptions that lay people make about the physiological mechanisms of the body, or the metaphors they use to describe their relationship to illness (e.g., a battle, a punishment, a message, etc.). In the third stage, the researcher would return to the interview subjects with a new set of questions that would seek to either affirm, modify, or discard the analytical themes derived from the initial coding of the interviews. This process can then be repeated until a thoroughly grounded theory is ready to be proposed. At every stage of the research, the researchers are obliged to follow the emerging data by revising their conceptions as new material is gathered, contradictions accounted for, commonalities categorized, and themes re-examined with further interviews.

Once the preliminary work is done and the hypothesis defined, it is time for the next research steps: choosing a research methodology, conducting a study, and drawing conclusions. These research steps are discussed below.

Making Connections: Classic Sociologists

Harriet Martineau: The First Woman Sociologist?

As was noted in Chapter 1, Harriet Martineau (1802–1876) was one of the first women sociologists in the 19th century. Particularly innovative was her early work on sociological methodology, How to Observe Manners and Morals (1838). In this volume she developed the ground work for a systematic social-scientific approach to studying human behaviour. She recognized that the issues of the researcher — subject relationship would have to be addressed differently in a social science as opposed to a natural science. The observer, or “traveller,” as she put it, needed to respect three criteria to obtain valid research: impartiality, critique, and sympathy. The impartial observer could not allow herself to be “perplexed or disgusted” by foreign practices that she could not personally reconcile herself with. Yet at the same time she saw the goal of sociology to be the fair but critical assessment of the moral status of a culture. In particular, the goal of sociology was to challenge forms of racial, sexual, or class domination in the name of autonomy: the right of every person to be a “self-directing moral being.” Finally, what distinguished the science of social observation from the natural sciences was that the researcher had to have unqualified sympathy for the subjects being studied (Lengermann & Niebrugge, 2007). This later became a central principle of Max Weber’s interpretive sociology, although it is not clear that Weber read Martineau’s work.

A large part of her research in the United States analyzed the situations of contradiction between stated public morality and actual moral practices. For example, she was fascinated with the way that the formal democratic right to free speech enabled slavery abolitionists to hold public meetings, but when the meetings were violently attacked by mobs, the abolitionists and not the mobs were accused of inciting the violence (Zeitlin, 1997). This emphasis on studying contradictions followed from the distinction she drew between morals — society’s collective ideas of permitted and forbidden behaviour — and manners — the actual patterns of social action and association in society. As she realized the difficulty in getting an accurate representation of an entire society based on a limited number of interviews, she developed the idea that one could identify key “Things” experienced by all people — age, gender, illness, death, etc. — and examine how they were experienced differently by a sample of people from different walks of life (Lengermann & Niebrugge, 2007). Martineau’s sociology, therefore, focused on surveying different attitudes toward “Things” and studying the anomalies that emerged when manners toward them contradicted a society’s formal morals.

2.2. Research Methods

Sociologists examine the world, see a problem or interesting pattern, and set out to study it. They use research methods to design a study — perhaps a positivist, quantitative method for conducting research and obtaining data, or perhaps an ethnographic study utilizing an interpretive framework. Planning the research design is a key step in any sociological study. When entering a particular social environment, a researcher must be careful. There are times to remain anonymous and times to be overt. There are times to conduct interviews and times to simply observe. Some participants need to be thoroughly informed; others should not know that they are being observed. A researcher would not stroll into a crime-ridden neighbourhood at midnight, calling out, “Any gang members around?” And if a researcher walked into a coffee shop and told the employees they would be observed as part of a study on work efficiency, the self-conscious, intimidated baristas might not behave naturally. The unique nature of human research subjects is that they can react to the researcher and change their behaviour under observation.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

The Hawthorne Effect

In the 1920s, leaders of a Chicago factory called Hawthorne Works commissioned a study to determine whether or not changing certain aspects of working conditions could increase or decrease worker productivity. Sociologists were surprised when the productivity of a test group increased when the lighting of their workspace was improved. They were even more surprised when productivity improved when the lighting of the workspace was dimmed. In fact almost every change of independent variable — lighting, breaks, work hours — resulted in an improvement of productivity. But when the study was over, productivity dropped again.

Why did this happen? In 1953, Henry A. Landsberger analyzed the study results to answer this question. He realized that employees’ productivity increased because sociologists were paying attention to them. The sociologists’ presence influenced the study results. Worker behaviours were altered not by the lighting but by the study itself. From this, sociologists learned the importance of carefully planning their roles as part of their research design (Franke & Kaul, 1978). Landsberger called the workers’ response the Hawthorne effect — people changing their behaviour because they know they are being watched as part of a study.

The Hawthorne effect is unavoidable in some research. In many cases, sociologists have to make the purpose of the study known for ethical reasons. Subjects must be aware that they are being observed, and a certain amount of artificiality may result (Sonnenfeld, 1985). Making sociologists’ presence invisible is not always realistic for other reasons. That option is not available to a researcher studying prison behaviours, early education, or the Ku Klux Klan. Researchers cannot just stroll into prisons, kindergarten classrooms, or Ku Klux Klan meetings and unobtrusively observe behaviours. In situations like these, other methods are needed. All studies shape the research design, while research design simultaneously shapes the study. Researchers choose methods that best suit their study topic and that fit with their overall goal for the research.

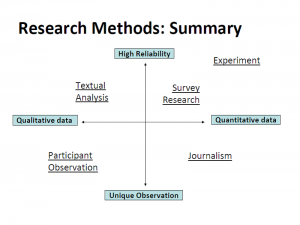

In planning a study’s design, sociologists generally choose from four widely used methods of social investigation: survey, experiment, field research, and textual or secondary data analysis (or use of existing sources). Every research method comes with pluses and minuses, and the topic of study strongly influences which method or methods are put to use.

1. Surveys

As a research method, a survey collects data from subjects who respond to a series of questions about behaviours and opinions, often in the form of a written questionnaire. The survey is one of the most widely used sociological research methods. The standard survey format allows individuals a level of anonymity in which they can express personal ideas.

At some point or another, everyone responds to some type of survey. The Statistics Canada census is an excellent example of a large-scale survey intended to gather sociological data. Customers also fill out questionnaires at stores or promotional events, responding to questions such as “How did you hear about the event?” and “Were the staff helpful?” You have probably picked up the phone and heard a caller ask you to participate in a political poll or similar type of survey: “Do you eat hot dogs? If yes, how many per month?” Not all surveys would be considered sociological research. Marketing polls help companies refine marketing goals and strategies; they are generally not conducted as part of a scientific study, meaning they are not designed to test a hypothesis or to contribute knowledge to the field of sociology. The results are not published in a refereed scholarly journal where design, methodology, results, and analyses are vetted.

Often, polls on TV do not reflect a general population, but are merely answers from a specific show’s audience. Polls conducted by programs such as American Idol or Canadian Idol represent the opinions of fans but are not particularly scientific. A good contrast to these are the Bureau of Broadcast Measurement (BBM) (now called Numeris) ratings, which determine the popularity of radio and television programming in Canada through scientific market research. Their researchers ask a large random sample of Canadians, age 12 and over, to fill out a television or radio diary for one week, noting the times and the broadcasters they listened to or viewed. Based on this methodology they are able to generate an accurate account of media consumers preferences, which are used to provide broadcast ratings for radio and television stations and define the characteristics of their core audiences.

Sociologists conduct surveys under controlled conditions for specific purposes. Surveys gather different types of information from people. While surveys are not great at capturing the ways people really behave in social situations, they are a great method for discovering how people feel and think — or at least how they say they feel and think. Surveys can track attitudes and opinions, political preferences, individual behaviours such as sleeping, driving, dietary, or texting habits, or factual information such as employment status, income, and education levels. A survey targets a specific population, people who are the focus of a study, such as university athletes, international students, or teenagers living with type 1 (juvenile-onset) diabetes.

Most researchers choose to survey a small sector of the population, or a sample: That is, a manageable number of subjects who represent a larger population. The success of a study depends on how well a population is represented by the sample. In a random sample, every person in a population has the same chance of being chosen for the study. According to the laws of probability, random samples represent the population as a whole. The larger the sample size, the more accurate the results will be in characterizing the population being studied. For practical purposes, however, a sample size of 1,500 people will give acceptably accurate results even if the population being researched was the entire adult population of Canada. For instance, an Ipsos Reid poll, if conducted as a nationwide random sampling, should be able to provide an accurate estimate of public opinion whether it contacts 1,500 or 10,000 people.

Typically surveys will include a figure that gives the margin of error of the survey results. Based on probabilities, this will give a range of values within which the true value of the population characteristic will be. This figure also depends on the size of a sample. For example, a political poll based on a sample of 1,500 respondents might state that if an election were called tomorrow the Conservative Party would get 30% of the vote plus or minus 2.5% based on a confidence interval of 95%. That is, there is a 5% chance that the true vote would fall outside of the range of 27.5% to 32.5%, or 1 time out of 20 if you were to conduct the poll 20 times. If the poll was based on a sample of 1,000 respondents, the margin of error would be higher, plus or minus 3.1%. This is significant, of course, because if the Conservatives are polling at 30% and the Liberals are polling at 28% the poll would be inconclusive about which party is actually ahead with regard to actual voter preferences.

Problems with accuracy or validity can result if sample sizes are too small because there is a stronger chance the sample size will not capture the actual distribution of characteristics of the whole population. In small samples the characteristics of specific individuals have a greater chance of influencing the results. The validity of surveys can also be threatened when part of the population is inadvertently excluded from the sample (e.g., telephone surveys that rely on land lines exclude people that use only cell phones) or when there is a low response rate. There is also a question of what exactly is being measured by the survey. In the BC election of 2013, polls found that the NDP had the largest popular support but on election day many people who said they would vote NDP did not actually vote, which resulted in a Liberal majority government.

After selecting subjects, the researcher develops a specific plan to ask a list of standardized questions and record responses. It is important to inform subjects of the nature and purpose of the study upfront. If they agree to participate, researchers thank the subjects and offer them a chance to see the results of the study if they are interested. The researchers present the subjects with an instrument or means of gathering the information. A common instrument is a structured written questionnaire in which subjects answer a series of set questions. For some topics, the researcher might ask yes-or-no or multiple-choice questions, allowing subjects to choose possible responses to each question.

This kind of quantitative data — research collected in numerical form that can be counted — is easy to tabulate. Just count up the number of “yes” and “no” answers or tabulate the scales of “strongly agree,” “agree,” “disagree,” etc. responses and chart them into percentages. This is also the chief drawback of questionnaires, however: their artificiality. In real life, there are rarely any unambiguously yes or no answers. Questionnaires can also ask more complex questions with more complex answers beyond yes, no, agree, strongly agree, or another option next to a check box. In those cases, the answers are subjective, varying from person to person. How do you plan to use your university education? Why do you follow Justin Bieber on Twitter? Those types of questions require short essay responses, and participants willing to take the time to write those answers will convey personal information about their beliefs, views, and attitudes.

Some topics that reflect internal subjective perspectives are impossible to observe directly. Sometimes they can be sensitive and difficult to discuss honestly in a public forum or with a stranger. People are more likely to share honest answers if they can respond to questions anonymously. This type of information is qualitative data — results that are subjective and often based on what is experienced in a natural setting. Qualitative information is harder to organize and tabulate. The researcher will end up with a wide range of responses, and some of which may be surprising. The benefit of written opinions, though, is the wealth of material that they provide.

An interview is a one-on-one conversation between the researcher and the subject, and is another way of conducting surveys on a topic. Interviews are similar to the short answer questions on surveys in that the researcher asks subjects a series of questions. They can be quantitative if the questions are standardized and have numerically quantifiable answers: Are you employed? (Yes=0, No=1); On a scale of 1 to 5 how would you describe your level of optimism? They can also be qualitative if participants are free to respond as they wish, without being limited by predetermined choices. In the back-and-forth conversation of an interview, a researcher can ask for clarification, spend more time on a subtopic, or ask additional questions. In an interview, a subject will ideally feel free to open up and answer questions that are often complex. There are no right or wrong answers. The subject might not even know how to answer the questions honestly. Questions such as “How did society’s view of alcohol consumption influence your decision whether or not to take your first sip of alcohol?” or “Did you feel that the divorce of your parents would put a social stigma on your family?” involve so many factors that the answers are difficult to categorize. A researcher needs to avoid steering or prompting the subject to respond in a specific way; otherwise, the results will prove to be unreliable. Obviously, a sociological interview is also not supposed to be an interrogation. The researcher will benefit from gaining a subject’s trust by empathizing or commiserating with a subject, and by listening without judgement.

2. Experiments

You have probably tested personal social theories. “If I study at night and review in the morning, I’ll improve my retention skills.” Or, “If I stop drinking soda, I’ll feel better.” Cause and effect. If this, then that. When you test a theory, your results either prove or disprove your hypothesis. One way researchers test social theories is by conducting an experiment, meaning they investigate relationships to test a hypothesis — a scientific approach. There are two main types of experiments: lab-based experiments, and natural or field experiments.

In a lab setting the research can be controlled so that, perhaps, more data can be recorded in a certain amount of time. In a natural or field-based experiment, the generation of data cannot be controlled, but the information might be considered more accurate since it was collected without interference or intervention by the researcher. As a research method, either type of sociological experiment is useful for testing if-then statements: if a particular thing happens, then another particular thing will result.

To set up a lab-based experiment, sociologists create artificial situations that allow them to manipulate variables. Classically, the sociologist selects a set of people with similar characteristics, such as age, class, race, or education. Those people are divided into two groups. One is the experimental group and the other is the control group. The experimental group is exposed to the independent variable(s) and the control group is not. This is similar to pharmaceutical drug trials in which the experimental group is given the test drug and the control group is given a placebo or sugar pill.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

An Experiment in Action: Mincome

A real-life example will help illustrate the experimental process in sociology. Between 1974 and 1979 an experiment was conducted in the small town of Dauphin, Manitoba (the “garden capital of Manitoba”). Each family received a modest monthly guaranteed income — a “mincome” — equivalent to a maximum of 60 percent of the “low-income cut-off figure” (a Statistics Canada measure of poverty, which varies with family size). The income was 50 cents per dollar less for families who had incomes from other sources. Families earning over a certain income level did not receive mincome. Families that were already collecting welfare or unemployment insurance were also excluded. The test families in Dauphin were compared with control groups in other rural Manitoba communities on a range of indicators such as number of hours worked per week, school performance, high school drop out rates, and hospital visits (Forget, 2011). A guaranteed annual income was seen at the time as a less costly, less bureaucratic public alternative for addressing poverty than the existing employment insurance and welfare programs. Today it is an active proposal being considered in Switzerland (Lowrey, 2013).

Intuitively, it seems logical that lack of income is the cause of poverty and poverty-related issues. One of the main concerns, however, was whether a guaranteed income would create a disincentive to work. The concept appears to challenge the principles of the Protestant work ethic (see the discussion of Max Weber in Chapter 1). The study did find very small decreases in hours worked per week: about 1 percent for men, 3 percent for married women, and 5 percent for unmarried women. Forget (2011) argues this was because the income provided an opportunity for people to spend more time with family and school, especially for young mothers and teenage girls. There were also significant social benefits from the experiment, including better test scores in school, lower high school drop out rates, fewer visits to hospital, fewer accidents and injuries, and fewer mental health issues.

Ironically, due to lack of guaranteed funding (and lack of political interest by the late 1970s), the data and results of the study were not analyzed or published until 2011. The data were archived and sat gathering dust in boxes. The mincome experiment demonstrated the benefits that even a modest guaranteed annual income supplement could have on health and social outcomes in communities. People seem to live healthier lives and get a better education when they do not need to worry about poverty. In her summary of the research, Forget notes that the impact of the income supplement was surprisingly large given that at any one time only about a third of the families were receiving the income and, for some families, the income amount would have been very small. The income benefit was largest for low-income working families, but the research showed that the entire community profited. The improvement in overall health outcomes for the community suggest that a guaranteed income would also result in savings for the public health system.

To test the benefits of tutoring, for example, the sociologist might expose the experimental group of students to tutoring while the control group does not receive tutoring. Then both groups would be tested for differences in performance to see if tutoring had an effect on the experimental group of students. As you can imagine, in a case like this, the researcher would not want to jeopardize the accomplishments of either group of students, so the setting would be somewhat artificial. The test would not be for a grade reflected on their permanent record, for example.

The Stanford Prison Experiment is perhaps one of the most famous sociological experiments ever conducted. In 1971, 24 healthy, middle-class male university students were selected to take part in a simulated jail environment to examine the effects of social setting and social roles on individual psychology and behaviour. They were randomly divided into 12 guards and 12 prisoners. The prisoner subjects were arrested at home and transported blindfolded to the simulated prison in the basement of the psychology building on the campus of Stanford University. Within a day of arriving the prisoners and the guards began to display signs of trauma and sadism respectively. After some prisoners revolted by blockading themselves in their cells, the guards resorted to using increasingly humiliating and degrading tactics to control the prisoners through psychological manipulation. The experiment had to be abandoned after only six days because the abuse had grown out of hand (Haney, Banks, & Zimbardo, 1973). While the insights into the social dynamics of authoritarianism it generated were fascinating, the Stanford Prison Experiment also serves as an example of the ethical issues that emerge when experimenting on human subjects.

3. Field Research

The work of sociology rarely happens in limited, confined spaces. Sociologists seldom study subjects in their own offices or laboratories. Rather, sociologists go out into the world. They meet subjects where they live, work, and play. Field research refers to gathering primary data from a natural environment without doing a lab experiment or a survey. It is a research method suited to an interpretive approach rather than to positivist approaches. To conduct field research, the sociologist must be willing to step into new environments and observe, participate, or experience those worlds. In fieldwork, the sociologists, rather than the subjects, are the ones out of their element. The researcher interacts with or observes a person or people, gathering data along the way. The key point in field research is that it takes place in the subject’s natural environment, whether it’s a coffee shop or tribal village, a homeless shelter or a care home, a hospital, airport, mall, or beach resort.

While field research often begins in a specific setting, the study’s purpose is to observe specific behaviours in that setting. Fieldwork is optimal for observing how people behave. It is less useful, however, for developing causal explanations of why they behave that way. From the small size of the groups studied in fieldwork, it is difficult to make predictions or generalizations to a larger population. Similarly, there are difficulties in gaining an objective distance from research subjects. It is difficult to know whether another researcher would see the same things or record the same data. We will look at three types of field research: participant observation, ethnography, and the case study.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

When Is Sharing Not Such a Good Idea?

Choosing a research methodology depends on a number of factors, including the purpose of the research and the audience for whom the research is intended. If we consider the type of research that might go into producing a government policy document on the effectiveness of safe injection sites for reducing the public health risks of intravenous drug use, we would expect public administrators to want “hard” (i.e., quantitative) evidence of high reliability to help them make a policy decision. The most reliable data would come from an experimental or quasi-experimental research model in which a control group can be compared with an experimental group using quantitative measures.

This approach has been used by researchers studying InSite in Vancouver (Marshall et al., 2011; Wood et al., 2006). InSite is a supervised safe-injection site where heroin addicts and other intravenous drug users can go to inject drugs in a safe, clean environment. Clean needles are provided and health care professionals are on hand to intervene in the case of overdoses or other medical emergency. It is a controversial program both because heroin use is against the law (the facility operates through a federal ministerial exemption) and because the heroin users are not obliged to quit using or seek therapy. To assess the effectiveness of the program, researchers compared the risky usage of drugs in populations before and after the opening of the facility and geographically near and distant to the facility. The results from the studies have shown that InSite has reduced both deaths from overdose and risky behaviours, such as the sharing of needles, without increasing the levels of crime associated with drug use and addiction.

On the other hand, if the research question is more exploratory (for example, trying to discern the reasons why individuals in the crack smoking subculture engage in the risky activity of sharing pipes), the more nuanced approach of fieldwork is more appropriate. The research would need to focus on the subcultural context, rituals, and meaning of sharing pipes, and why these phenomena override known health concerns. Graduate student Andrew Ivsins at the University of Victoria studied the practice of sharing pipes among 13 habitual users of crack cocaine in Victoria, B.C. (Ivsins, 2010). He met crack smokers in their typical setting downtown and used an unstructured interview method to try to draw out the informal norms that lead to sharing pipes. One factor he discovered was the bond that formed between friends or intimate partners when they shared a pipe. He also discovered that there was an elaborate subcultural etiquette of pipe use that revolved around the benefit of getting the crack resin smokers left behind. Both of these motives tended to outweigh the recognized health risks of sharing pipes (such as hepatitis) in the decision making of the users. This type of research was valuable in illuminating the unknown subcultural norms of crack use that could still come into play in a harm reduction strategy such as distributing safe crack kits to addicts.

Participant Observation

In 2000, a comic writer named Rodney Rothman wanted an insider’s view of white-collar work. He slipped into the sterile, high-rise offices of a New York “dot com” agency. Every day for two weeks, he pretended to work there. His main purpose was simply to see if anyone would notice him or challenge his presence. No one did. The receptionist greeted him. The employees smiled and said good morning. Rothman was accepted as part of the team. He even went so far as to claim a desk, inform the receptionist of his whereabouts, and attend a meeting. He published an article about his experience in The New Yorker called “My Fake Job” (2000). Later, he was discredited for allegedly fabricating some details of the story and The New Yorker issued an apology. However, Rothman’s entertaining article still offered fascinating descriptions of the inside workings of a dot com company and exemplified the lengths to which a sociologist will go to uncover material.

Rothman had conducted a form of study called participant observation, in which researchers join people and participate in a group’s routine activities for the purpose of observing them within that context. This method lets researchers study a naturally occurring social activity without imposing artificial or intrusive research devices, like fixed questionnaire questions, onto the situation. A researcher might go to great lengths to get a firsthand look into a trend, institution, or behaviour. Researchers temporarily put themselves into “native” roles and record their observations. A researcher might work as a waitress in a diner, or live as a homeless person for several weeks, or ride along with police officers as they patrol their regular beat. Often, these researchers try to blend in seamlessly with the population they study, and they may not disclose their true identity or purpose if they feel it would compromise the results of their research.

At the beginning of a field study, researchers might have a question: “What really goes on in the kitchen of the most popular diner on campus?” or “What is it like to be homeless?” Participant observation is a useful method if the researcher wants to explore a certain environment from the inside. Field researchers simply want to observe and learn. In such a setting, the researcher will be alert and open minded to whatever happens, recording all observations accurately. Soon, as patterns emerge, questions will become more specific, observations will lead to hypotheses, and hypotheses will guide the researcher in shaping data into results.

In a study of small town America conducted by sociological researchers John S. Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd, the team altered their purpose as they gathered data. They initially planned to focus their study on the role of religion in American towns. As they gathered observations, they realized that the effect of industrialization and urbanization was the more relevant topic of this social group. The Lynds did not change their methods, but they revised their purpose. This shaped the structure of Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture, their published results (Lynd & Lynd, 1959).

The Lynds were upfront about their mission. The townspeople of Muncie, Indiana knew why the researchers were in their midst. But some sociologists prefer not to alert people to their presence. The main advantage of covert participant observation is that it allows the researcher access to authentic, natural behaviours of a group’s members. The challenge, however, is gaining access to a setting without disrupting the pattern of others’ behaviour. Becoming an inside member of a group, organization, or subculture takes time and effort. Researchers must pretend to be something they are not. The process could involve role playing, making contacts, networking, or applying for a job. Once inside a group, some researchers spend months or even years pretending to be one of the people they are observing. However, as observers, they cannot get too involved. They must keep their purpose in mind and apply the sociological perspective. That way, they illuminate social patterns that are often unrecognized. Because information gathered during participant observation is mostly qualitative, rather than quantitative, the end results are often descriptive or interpretive. The researcher might present findings in an article or book, describing what he or she witnessed and experienced.

This type of research is what journalist Barbara Ehrenreich conducted for her book Nickel and Dimed. One day over lunch with her editor, as the story goes, Ehrenreich mentioned an idea. “How can people exist on minimum-wage work? How do low-income workers get by?” she wondered. “Someone should do a study.” To her surprise, her editor responded, “Why don’t you do it?” That is how Ehrenreich found herself joining the ranks of the low-wage service sector. For several months, she left her comfortable home and lived and worked among people who lacked, for the most part, higher education and marketable job skills. Undercover, she applied for and worked minimum wage jobs as a waitress, a cleaning woman, a nursing home aide, and a retail chain employee. During her participant observation, she used only her income from those jobs to pay for food, clothing, transportation, and shelter. She discovered the obvious: that it’s almost impossible to get by on minimum wage work. She also experienced and observed attitudes many middle- and upper-class people never think about. She witnessed firsthand the treatment of service work employees. She saw the extreme measures people take to make ends meet and to survive. She described fellow employees who held two or three jobs, worked seven days a week, lived in cars, could not pay to treat chronic health conditions, got randomly fired, submitted to drug tests, and moved in and out of homeless shelters. She brought aspects of that life to light, describing difficult working conditions and the poor treatment that low-wage workers suffer.

Ethnography

Ethnography is the extended observation of the social perspective and cultural values of an entire social setting. Researchers seek to immerse themselves in the life of a bounded group by living and working among them. Often ethnography involves participant observation, but the focus is the systematic observation of an entire community. The heart of an ethnographic study focuses on how subjects view their own social standing and how they understand themselves in relation to a community. It aims at developing a “thick description” of people’s behaviour that describes not only the behaviour itself but the layers of meaning that form the context of the behaviour (Geertz, 1973). An ethnographic study might observe, for example, a small Newfoundland fishing town, an Inuit community, a scientific research laboratory, a backpacker’s hostel, a private boarding school, or Disney World. These places all have borders. People live, work, study, or vacation within those borders. People are there for a certain reason and therefore behave in certain ways and respect certain cultural norms. An ethnographer would commit to spending a determined amount of time studying every aspect of the chosen place, taking in as much as possible, and keeping careful notes on his or her observations. A sociologist studying a ayahuasca ceremonies in the Amazon might learn the language, watch the way shamans go about their daily lives, ask individuals about the meaning of different aspects of the activity, study the group’s cosmology, and then write a paper about it. To observe a Buddhist retreat centre, an ethnographer might sign up for a retreat and attend as a guest for an extended stay, observe and record how people experience spirituality in this setting, and collate the material into results.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

The Feminist Perspective: Institutional Ethnography

The Case Study

Sometimes a researcher wants to study one specific person or event. A case study is an in-depth analysis of a single event, situation, or individual. To conduct a case study, a researcher examines existing sources like documents and archival records, conducts interviews, engages in direct observation, and even participant observation, if possible. Researchers might use this method to study a single case of, for example, a foster child, drug lord, cancer patient, criminal, or rape victim. However, a major criticism of the case study as a method is that a developed study of a single case, while offering depth on a topic, does not provide enough evidence to form a generalized conclusion. In other words, it is difficult to make universal claims based on just one person, since one person does not verify a pattern. This is why most sociologists do not use case studies as a primary research method.

However, case studies are useful when the single case is unique. In these instances, a single case study can add tremendous knowledge to a certain discipline. For example, a feral child, also called “wild child,” is one who grows up isolated from human beings. Feral children grow up without social contact and language, which are elements crucial to a “civilized” child’s development. These children mimic the behaviours and movements of animals, and often invent their own language. There are only about 100 cases of feral children in the world. As you may imagine, a feral child is a subject of great interest to researchers. Feral children provide unique information about child development because they have grown up outside of the parameters of normal child development. And since there are very few feral children, the case study is the most appropriate method for researchers to use in studying the subject. At age three, a Ukrainian girl named Oxana Malaya suffered severe parental neglect. She lived in a shed with dogs, eating raw meat and scraps. Five years later, a neighbour called authorities and reported seeing a girl who ran on all fours, barking. Officials brought Oxana into society, where she was cared for and taught some human behaviours, but she never became fully socialized. She has been designated as unable to support herself and now lives in a mental institution (Grice, 2006). Case studies like this offer a way for sociologists to collect data that may not be collectable by any other method.

4. Secondary Data or Textual Analysis

While sociologists often engage in original research studies, they also contribute knowledge to the discipline through secondary data or textual analysis. Secondary data do not result from firsthand research collected from primary sources, but are drawn from the already-completed work of other researchers. Sociologists might study texts written by historians, economists, teachers, or early sociologists. They might search through periodicals, newspapers, or magazines from any period in history. Using available information not only saves time and money, but it can add depth to a study. Sociologists often interpret findings in a new way, a way that was not part of an author’s original purpose or intention. To study how women were encouraged to act and behave in the 1960s, for example, a researcher might watch movies, televisions shows, and situation comedies from that period. Or to research changes in behaviour and attitudes due to the emergence of television in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a sociologist would rely on new interpretations of secondary data. Decades from now, researchers will most likely conduct similar studies on the advent of mobile phones, the internet, or Facebook.

One methodology that sociologists employ with secondary data is content analysis. Content analysis is a quantitative approach to textual research that selects an item of textual content (i.e., a variable) that can be reliably and consistently observed and coded, and surveys the prevalence of that item in a sample of textual output. For example, Gilens (1996) wanted to find out why survey research shows that the American public substantially exaggerates the percentage of African Americans among the poor. He examined whether media representations influence public perceptions and did a content analysis of photographs of poor people in American news magazines. He coded and then systematically recorded incidences of three variables: (1) race: white, black, indeterminate; (2) employed: working, not working; and (3) age. Gilens discovered that not only were African Americans markedly overrepresented in news magazine photographs of poverty, but that the photos also tended to under represent “sympathetic” subgroups of the poor—the elderly and working poor—while over representing less sympathetic groups—unemployed, working age adults. Gilens concluded that by providing a distorted representation of poverty, U.S. news magazines “reinforce negative stereotypes of blacks as mired in poverty and contribute to the belief that poverty is primarily a ‘black problem’” (1996).