Chapter 4. Socialization

Learning Objectives

5.1. Theories of Self Development

- Describe the self as a social structure.

- Explain the four stages of role development in child socialization.

- Analyze the formation of a gender schema in the socialization of gender roles.

5.2. Why Socialization Matters

- Analyze the importance of socialization for individuals and society.

- Explain the nature versus nurture debate.

- Describe both the conformity of behaviour in society and the existence of individual uniqueness.

- Learn the roles of families and peer groups in socialization.

- Understand how we are socialized through formal institutions like schools, workplaces, and the government.

5.4. Socialization Across the Life Course

- Explain how people are socialized into new roles at age-related transition points.

- Describe when and how resocialization occurs.

Introduction to Socialization

In the summer of 2005, police detective Mark Holste followed an investigator from the Department of Children and Families to a home in Plant City, Florida. They were there to look into a statement from the neighbour concerning a shabby house on Old Sydney Road. A small girl was reported peering from one of its broken windows. This seemed odd because no one in the neighbourhood had seen a young child in or around the home, which had been inhabited for the past three years by a woman, her boyfriend, and two adult sons.

Who Was the Mysterious Girl in the Window?

Entering the house, Detective Holste and his team were shocked. It was the worst mess they had ever seen: infested with cockroaches, smeared with feces and urine from both people and pets, and filled with dilapidated furniture and ragged window coverings.

Detective Holste headed down a hallway and entered a small room. That is where he found a little girl with big, vacant eyes staring into the darkness. A newspaper report later described the detective’s first encounter with the child:

She lay on a torn, moldy mattress on the floor. She was curled on her side … her ribs and collarbone jutted out … her black hair was matted, crawling with lice. Insect bites, rashes and sores pocked her skin…. She was naked — except for a swollen diaper.… Her name, her mother said, was Danielle. She was almost seven years old. (DeGregory, 2008)

Detective Holste immediately carried Danielle out of the home. She was taken to a hospital for medical treatment and evaluation. Through extensive testing, doctors determined that, although she was severely malnourished, Danielle was able to see, hear, and vocalize normally. Still, she would not look anyone in the eyes, did not know how to chew or swallow solid food, did not cry, did not respond to stimuli that would typically cause pain, and did not know how to communicate either with words or simple gestures such as nodding “yes” or “no.” Likewise, although tests showed she had no chronic diseases or genetic abnormalities, the only way she could stand was with someone holding onto her hands, and she “walked sideways on her toes, like a crab” (DeGregory, 2008).

What had happened to Danielle? Put simply: beyond the basic requirements for survival, she had been neglected. Based on their investigation, social workers concluded that she had been left almost entirely alone in rooms like the one where she was found. Without regular interaction—the holding, hugging, talking, the explanations and demonstrations given to most young children—she had not learned to walk or to speak, to eat or to interact, to play or even to understand the world around her. From a sociological point of view, Danielle had not had been socialized.

Socialization is the process through which people are taught to be proficient members of a society. It describes the ways that people come to understand societal norms and expectations, to accept society’s beliefs, and to be aware of societal values. It also describes the way people come to be aware of themselves and to reflect on the suitability of their behaviour in their interactions with others. Socialization occurs as people engage and disengage in a series of roles throughout life. Each role, like the role of son or daughter, student, friend, employee, etc., is defined by the behaviour expected of a person who occupies a particular position.

Socialization is not the same as socializing (interacting with others, like family, friends, and coworkers); to be precise, it is a sociological process that occurs through socializing. As Danielle’s story illustrates, even the most basic of human activities are learned. You may be surprised to know that even physical tasks like sitting, standing, and walking had not automatically developed for Danielle as she grew. Without socialization, Danielle had not learned about the material culture of her society (the tangible objects a culture uses): For example, she could not hold a spoon, bounce a ball, or use a chair for sitting. She also had not learned its nonmaterial culture, such as its beliefs, values, and norms. She had no understanding of the concept of family, did not know cultural expectations for using a bathroom for elimination, and had no sense of modesty. Most importantly, she hadn’t learned to use the symbols that make up language—through which we learn about who we are, how we fit with other people, and the natural and social worlds in which we live.

In the following sections, we will examine the importance of the complex process of socialization and learn how it takes place through interaction with many individuals, groups, and social institutions. We will explore how socialization is not only critical to children as they develop, but how it is a lifelong process through which we become prepared for new social environments and expectations in every stage of our lives. But first, we will turn to scholarship about self development, the process of coming to recognize a sense of a “self” that is then able to be socialized.

5.1. Theories of Self Development

Danielle’s case underlines an important point that sociologists make about socialization, namely that the human self does not emerge “naturally” as a process driven by biological mechanisms. What is a self? What does it mean to have a self? The self refers to a person’s distinct sense of identity. It is who we are for ourselves and who we are for others. It has consistency and continuity through time and a coherence that distinguishes us as persons. However, there is something always precarious and incomplete about the self. Selves change through the different stages of life; sometimes they do not measure up to the ideals we hold for ourselves or others, and sometimes they can be wounded by our interactions with others or thrown into crisis. As Zygmunt Bauman put it, one’s distinct sense of identity is a “postulated self,” a “horizon towards which I strive and by which I assess, censure and correct my moves” (2004). It is clear, however, that the self does not develop in the absence of socialization. The self is a social product.

The American sociologist George Herbert Mead is often seen as the founder of the school of symbolic interactionism in sociology, although he referred to himself a social behaviourist. His conceptualization of the self has been very influential. Mead defines the emergence of the self as a thoroughly social process: “The self, as that which can be an object to itself, is essentially a social structure, and it arises in social experience” (Mead, 1934).

In this description, you should notice first that the key quality of the self that Mead is concerned with is the ability to be reflexive or self-aware (i.e., to be an “object” to oneself). One can think about oneself, or feel how one is feeling. Second, this key quality of the self can only arise in a social context through social interactions with others. In Charles Horton Cooley’s concept of the “looking glass self,” others, and their attitudes towards us, are like mirrors in which we are able to see ourselves and formulate an idea of who we are (Cooley, 1902). Without others, or without society, the self does not exist: “[I]t is impossible to conceive of a self arising outside of social experience” (Mead, 1934, p. 293).

Even when the self is alone for extended periods of time (hermits, prisoners in isolation, etc.), an internal conversation goes on that would not be possible if the individual had not been socialized already. The examples of feral children like Victor of Aveyron or children like Danielle who have been raised under conditions of extreme social deprivation attest to the difficulties these individuals confront when trying to develop this reflexive quality of humanity. They often cannot use language, form intimate relationships, or play games. So socialization is not simply the process through which people learn the norms and rules of a society, it also is the process by which people become aware of themselves as they interact with others. It is the process through which people are able to become people in the first place.

The necessity for early social contact was demonstrated by the research of Harry and Margaret Harlow. From 1957–1963, the Harlows conducted a series of experiments studying how rhesus monkeys, which behave a lot like people, are affected by isolation as babies. They studied monkeys raised under two types of “substitute” mothering circumstances: a mesh and wire sculpture, or a soft terry cloth “mother.” The monkeys systematically preferred the company of a soft, terry cloth substitute mother (closely resembling a rhesus monkey) that was unable to feed them, to a mesh and wire mother that provided sustenance via a feeding tube. This demonstrated that while food was important, social comfort was of greater value (Harlow & Harlow, 1962; Harlow, 1971). Later experiments testing more severe isolation revealed that such deprivation of social contact led to significant developmental and social challenges later in life.

Theories of Self Development

When we are born, we have a genetic makeup and biological traits. However, who we are as human beings develops through social interaction. Many scholars, both in the fields of psychology and sociology, have described the process of self development as a precursor to understanding how that “self” becomes socialized.

Sigmund Freud

Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) was one of the most influential modern scientists to put forth a theory about how people develop a sense of self. He believed that personality and sexual development were closely linked, and he divided the maturation process into universal psychosexual stages: oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital. Each stage involves the child’s discovery and passage through the bodily pleasures linked to breastfeeding, toilet training, and sexual awareness (Freud, 1905).

Key to Freud’s approach to child development was his emphasis on tracing the formations of desire and pleasure in a child’s life. The child is seen to be at the centre of a tricky negotiation between internal, instinctual drives for gratification (the pleasure principle) and external, social demands that the child repress those drives in order to conform to the rules and regulations of civilization (the reality principle). Failure to resolve the traumatic tensions and impasses of childhood psychosexual development results in emotional and psychological consequences throughout adulthood. For example, according to Freud the failure of a child to properly engage in or disengage from a specific stage of development results in predictable outcomes later in life. An adult with an oral fixation may indulge in overeating or binge drinking. An anal fixation may produce a neat freak (hence the term “anal retentive”), while a person stuck in the phallic stage may be promiscuous or emotionally immature.

Psychologist Erik Erikson (1902–1994) created a theory of personality development based on the work of Freud. However, Erikson was also interested in the social and cultural dimensions of Freud’s child development schema (1963). Following Freud, he noted that each stage of psychosexual child development was associated with the formation of basic emotional structures in adulthood. The outcome of the oral stage will determine whether someone is trustful or distrustful as an adult; the outcome of the anal stage, whether they will be confident and generous or ashamed and doubtful; the outcome of the genital stage, whether they will be full of initiative or guilt.

Erikson retained Freud’s idea that the stages of child development were universal, but he believed that different cultures handled them differently. Child-raising techniques varied in line with the dominant social formation of their societies. So, for example, the tradition in the communally-based Sioux First Nation was not to wean infants but to breastfeed until the infant lost interest. This tradition created trust between the infant and his or her mother, and eventually trust between the child and the tribal group as a whole. On the other hand, modern industrial societies practice early weaning of children, which leads to a more distrustful character structure. Children develop a possessive disposition toward objects that carries with them through to adulthood. The result of early weaning is that the child is eager to get things and grab hold of things in lieu of the experience of generosity and comfort in being held.

Societies like the Sioux, in which individuals rely heavily on each other and on the group to survive in a hostile environment, will handle child training in a different manner and with different outcomes than societies based on individualism, competition, self-reliance, and self-control (Erikson, 1963).

Making Connections: Sociological Concepts

Sociology or Psychology: What’s the Difference?

You might be wondering: If sociologists and psychologists are both interested in people and their behaviour, how are these two disciplines different? What do they agree on, and where do their ideas diverge? The answers are complicated, but the distinction is important to scholars in both fields.As a general difference, we might say that while both disciplines are interested in human behaviour, psychologists are focused on how the mind influences that behaviour, while sociologists study the role of society in shaping both behaviour and the mind. Psychologists are interested in people’s mental development and how their minds process their world. Sociologists are more likely to focus on how different aspects of society contribute to an individual’s relationship with the world. Another way to think of the difference is that psychologists tend to look inward to qualities of individuals (mental health, emotional processes, cognitive processing), while sociologists tend to look outward to qualities of social context (social institutions, cultural norms, interactions with others) to understand human behaviour.Émile Durkheim (1958–1917) was the first to make this distinction in research, when he attributed differences in suicide rates among people to social causes (religious differences) rather than to psychological causes (like their mental well-being) (Durkheim, 1897). Today, we see this same distinction. For example, a sociologist studying how a couple gets to the point of their first kiss on a date might focus her research on cultural norms for dating, social patterns of romantic activity in history, or the influence of social background on romantic partner selection. How is this process different for seniors than for teens, for example? A psychologist would more likely be interested in the person’s romantic history, psychological type, or the mental processing of sexual desire.

The point that sociologists like Durkheim would make is that an analysis of individuals at the psychological level cannot adequately account for social variability of behaviours, for example, the difference in suicide rates of Catholics and Protestants, or the difference in dating scripts across cultures or historical periods. Sometimes sociology and psychology can combine in interesting ways, however. Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism (1979) argued that the neurotic personality was a product of an earlier Protestant ethic style of competitive capitalism; whereas, late postindustrial consumer capitalism is conducive to narcissistic personality structures (the “me” society).

Charles Horton Cooley

One of the pioneering contributors to sociological perspectives on self-development was the American Charles Horton Cooley (1864–1929). Cooley asserted that people’s self understanding is constructed, in part, by their perception of how others view them — a process termed “the looking glass self” (Cooley, 1902). According to Cooley, we base our image on what we think other people see (1902). We imagine how we must appear to others, then react to this speculation. We don certain clothes, prepare our hair in a particular manner, wear makeup, use cologne, and the like — all with the notion that our presentation of ourselves is going to affect how others perceive us. We expect a certain reaction, and, if lucky, we get the one we desire and feel good about it.Cooley believed that our sense of self is not based on some internal source of individuality. Rather, we imagine how we look to others, draw conclusions based on their reactions to us, and then develop our personal sense of self. In other words, people’s reactions to us are like a mirror in which we are reflected. We live a mirror image of ourselves. “The imaginations people have of one another are the solid facts of society” (Cooley, 1902).The self or “self idea” is thoroughly social. It is not an expression of the internal essence of the individual, or of the individual’s unique psychology which emerges as the individual matures. It is based on how we imagine we appear to others. It is not how we actually appear to others but our projection of what others think or feel towards us. This projection defines how we feel about ourselves and who we feel ourselves to be. The development of a self, therefore, involves three elements in Cooley’s analysis: “the imagination of our appearance to the other person; the imagination of his judgement of that appearance, and some sort of self-feeling, such as pride or mortification” (Cooley, 1902).

George Herbert Mead

Later, George Herbert Mead (1863–1931) advanced a more detailed sociological approach to the self. He agreed that the self, as a person’s distinct identity, is only developed through social interaction. As we noted above, he argued that the crucial component of the self is its capacity for self reflection, its capacity to be “an object to itself” (Mead, 1934). On this basis, he broke the self down into two components or “phases,” the “I” and the “me.” The “me” represents the part of the self in which one recognizes the “organized sets of attitudes” of others toward the self. It is who we are in other’s eyes: our roles, our “personalities,” our public personas. The “I,” on the other hand, represents the part of the self that acts on its own initiative or responds to the organized attitudes of others. It is the novel, spontaneous, unpredictable part of the self: the part of the self that embodies the possibility of change or undetermined action. The self is always caught up in a social process in which one flips back and forth between two distinguishable phases, the I and the me, as one mediates between one’s own individual actions and individual responses to various social situations and the attitudes of the community.

This flipping back and forth is the condition of our being able to be social. It is not an ability that we are born with (Mead, 1934). The case of Danielle, for example, illustrates what happens when social interaction is absent from early experience: She had no ability to see herself as others would see her. From Mead’s point of view, she had no “self.” Without others, or without society, the self cannot exist: “[I]t is impossible to conceive of a self arising outside of social experience” (Mead, 1934).

How do we get from being newborns to being humans with “selves”? In Mead’s theory of childhood development, the child develops through stages in which the child’s increasing ability to play roles attests to his or her increasing solidification of a social sense of self. A role is the behaviour expected of a person who occupies particular social status or position in society. In learning to play roles one also learns how to put oneself in the place of another, to see through another’s eyes. At one point in their life, a child simply cannot play a game like baseball; they do not “get it” because they cannot insert themselves into the complex role of the player. They cannot see themselves from the point of view of all the other players on the field or figure out their place within a rule bound sequence of activities. At another point in their life, a child becomes able to learn how to play. Mead developed a specifically sociological theory of the path of development that all people go through by focusing on the developing capacity to put oneself in the place of another, or role play: the four stages of child socialization.

Four Stages of Child Socialization

During the preparatory stage, children are only capable of imitation: They have no ability to imagine how others see things. They copy the actions of people with whom they regularly interact, such as their mothers and fathers. A child’s baby talk is a reflection of its inability to make an object of him- or herself. The separation of I and me does not yet exist in an organized manner to enable the child to relate to him- or herself.

This is followed by the play stage, during which children begin to imitate and take on roles that another person might have. Thus, children might try on a parent’s point of view by acting out “grownup” behaviour, like playing dress up and acting out the mom role, or talking on a toy cell phone the way they see their father do.

He plays that he is, for instance, offering himself something, and he buys it; he gives a letter to himself and takes it away; he addresses himself as a parent, as a teacher; he arrests himself as a policeman…. The child says something in one character and responds in another character, and then his responding in another character is a stimulus to himself in the first character, and so the conversation goes on. (Mead, 1934)

However, children are still not able to take on roles in a consistent and coherent manner. Role play is very fluid and transitory, and children flip in and out of roles easily. They “pass[..] from one role to another just as a whim takes [them]” (Mead, 1934).

During the game stage, children learn to consider several specific roles at the same time and how those roles interact with each other. They learn to understand interactions involving different people with a variety of purposes. They understand that role play in each situation involves following a consistent set of rules and expectations. For example, a child at this stage is likely to be aware of the different responsibilities of people in a restaurant who together make for a smooth dining experience: someone seats you, another takes your order, someone else cooks the food, while yet another person clears away dirty dishes, etc.

Mead uses the example of a baseball game. “If we contrast play with the situation in an organized game, we note the essential difference that the child who plays in a game must be ready to take the attitude of everyone else involved in that game, and that these different roles must have a definite relationship to each other” (Mead, 1934). At one point in learning to play baseball, children do not get it that when they hit the ball they need to run, or that after their turn someone else gets a turn to bat. In order for baseball to work, the players not only have to know what the rules of the game are, and what their specific role in the game is (batter, catcher, first base, etc.), but know simultaneously the role of every other player on the field. They have to see the game from the perspective of others. “What he does is controlled by his being everyone else on that team, at least in so far as those attitudes affect his own particular response” (Mead, 1934). The players have to be able to anticipate the actions of others and adjust or orient their behaviour accordingly. Role play in games like baseball involves the understanding that ones own role is tied to the roles of several people simultaneously and that these roles are governed by fixed, or at least mutually recognized, rules and expectations. Finally, children develop, understand, and learn the idea of the generalized other, the common behavioural expectations of general society. By this stage of development, an individual is able to internalize how he or she is viewed, not simply from the perspective of several specific others, but from the perspective of the generalized other or “organized community.” Being able to guide one’s actions according to the attitudes of the generalized other provides the basis of having a “self” in the sociological sense. “[O]nly in so far as he takes the attitudes of the organized social group to which he belongs toward the organized, cooperative social activity or set of such activities in which that group as such is engaged, does he develop a complete self” (Mead, 1934). This capacity defines the conditions of thinking, of language, and of society itself as the organization of complex co-operative processes and activities.

It is in the form of the generalized other that the social process influences the behavior of the individuals involved in it and carrying it on, that is, that the community exercises control over the conduct of its individual members; for it is in this form that the social process or community enters as a determining factor into the individual’s thinking. In abstract thought the individual takes the attitude of the generalized other toward himself, without reference to its expression in any particular other individuals; and in concrete thought he takes that attitude in so far as it is expressed in the attitudes toward his behavior of those other individuals with whom he is involved in the given social situation or act. But only by taking the attitude of the generalized other toward himself, in one or another of these ways, can he think at all; for only thus can thinking — or the internalized conversation of gestures which constitutes thinking-occur. And only through the taking by individuals of the attitude or attitudes of the generalized other toward themselves is the existence of a universe of discourse, as that system of common or social meanings which thinking presupposes at its context, rendered possible. (Mead, 1934)

Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development and Gilligan’s Theory of Gender Differences

Moral development is an important part of the socialization process. The term refers to the way people learn what society considered to be “good” and “bad,” which is important for a smoothly functioning society. Moral development prevents people from acting on unchecked urges, instead considering what is right for society and good for others. Lawrence Kohlberg (1927–1987) was interested in how people learn to decide what is right and what is wrong. To understand this topic, he developed a theory of moral development that includes three levels: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional.

In the preconventional stage, young children, who lack a higher level of cognitive ability, experience the world around them only through their senses. It is not until the teen years that the conventional theory develops, when youngsters become increasingly aware of others’ feelings and take those into consideration when determining what’s good and bad. The final stage, called postconventional, is when people begin to think of morality in abstract terms, such as North Americans believing that everyone has equal rights and freedoms. At this stage, people also recognize that legality and morality do not always match up evenly (Kohlberg, 1981). When hundreds of thousands of Egyptians turned out in 2011 to protest government autocracy, they were using postconventional morality. They understood that although their government was legal, it was not morally correct.

Carol Gilligan (b. 1936), recognized that Kohlberg’s theory might show gender bias since his research was conducted only on male subjects. Would female study subjects have responded differently? Would a female social scientist notice different patterns when analyzing the research? To answer the first question, she set out to study differences between how boys and girls developed morality. Gilligan’s research demonstrated that boys and girls do, in fact, have different understandings of morality. Boys tend to have a justice perspective, placing emphasis on rules, laws, and individual rights. They learn to morally view the world in terms of categorization and separation. Girls, on the other hand, have a care and responsibility perspective; they are concerned with responsibilities to others and consider people’s reasons behind behaviour that seems morally wrong. They learn to morally view the world in terms of connectedness.

Gilligan also recognized that Kohlberg’s theory rested on the assumption that the justice perspective was the right, or better, perspective. Gilligan, in contrast, theorized that neither perspective was “better”: The two norms of justice served different purposes. Ultimately, she explained that boys are socialized for a work environment where rules make operations run smoothly, while girls are socialized for a home environment where flexibility allows for harmony in caretaking and nurturing (Gilligan, 1982, 1990).

The Socialization of Gender

How do girls and boys learn different gender roles? Gender differences in the ways boys and girls play and interact develop from a very early age, sometimes despite the efforts of parents to raise them in a gender neutral way. Little boys seem inevitably to enjoy running around playing with guns and projectiles, while little girls like to study the effects of different costumes on toy dolls. Peggy Orenstein (2012) describes how her two-year-old daughter happily wore her engineer outfit and took her Thomas the Tank Engine lunchbox to the first day of preschool. It only took one little boy to say to her that “girls don’t like trains!” for her to ditch Thomas and move on to more gender “appropriate” concerns like princesses. If gender preferences are not inborn or biologically hard-wired, how do sociologists explain them?

As the Thomas the Tank Engine example suggests, doing gender — performing tasks based upon the gender assigned by society — is learned through interaction with others in much the same way that Mead and Cooley described for socialization in general. Children learn gender through direct feedback from others, particularly when they are censured for violating gender norms. Gender is in this sense an accomplishment rather than an innate trait. It takes place through the child’s developing awareness of self. Whereas in the Freudian model of gender development children become aware of their own genitals and spontaneously generate erotic fantasies and speculations whose resolution lead them to identify with their mother or father, in the sociological model, it is adults’ awareness of a child’s genitals that leads to gender labelling, differential reinforcement and the assumption of gender roles.

From a very early age children develop a gender schema, a rudimentary image of gender differences, that enables them to make decisions about appropriate styles of play and behaviour (Fagot & Leinbach, 1989). As they integrate their sense of self into this developing schema, they gradually adopt consistent and stable gender roles. Consistency and stability do not mean that the gender roles that are learned are permanent, however, as would be suggested by a biological or hard-wired model of gender. Physical expressions of gender such as “throwing like a girl” can be transformed into a new stable gender schema when the little girl joins a softball league.

Fagot and Leinbach’s (1986, 1989) research into the development of gender schemas showed that very young children, averaging about two years old, could not correctly classify photographs of adults and children by their gender; whereas, slightly older children, averaging 2.5 years old, could. They concluded that the younger children had not yet developed a gender schema. They also observed that the older children who could correctly classify the photos by gender demonstrated gender specific play; they tended to choose same-gender play groups and girls were less aggressive in their play. The older children were integrating their sense of self into their gender schemas and behaving accordingly.

Similarly, when they studied children at home, they found that children at age 1.5 could not assign gender to photographs correctly and did not engage in gender-typed play. However, by age 2.25 years about half of the children could classify the photos and were engaging in gender specific play. These “early labellers” were distinguished from those who could not classify photos by the way their parents interacted with them. Parents of early adopters were more likely to use differential reinforcement in the form of positive and negative responses to gender-typed toy play.

It is interesting, with respect to the difference between the Freudian and sociological models of gender socialization, that the gender schemas of young children develop with respect to external cultural signs of gender rather than biological markers of genital differences. Sandra Bem (1989) showed young children photos of either a naked child or a child dressed in boys or girls clothing. The younger children had difficulty classifying the naked photos but could classify the clothed photos. They did not have an understanding of biological sex constancy — i.e. the ability to determine sex based on anatomy regardless of gender signs — but used cultural signs of gender like clothing or hair style to determine gender. Moreover, it was the gender schema and not the recognition of anatomical differences that first determined their choice of gender-typed toys and gender-typed play groups. Bem suggested that “children who can label the sexes but do not understand anatomical stability are not yet confident that they will always remain in one gender group” (1989).

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

What a Pretty Little Lady!

“What a cute dress!” “I like the ribbons in your hair.” “Wow, you look so pretty today.” According to Lisa Bloom, author of Think: Straight Talk for Women to Stay Smart in a Dumbed Down World, most of us use pleasantries like these when we first meet little girls. “So what?” you might ask. Bloom asserts that we are too focused on the appearance of young girls, and as a result our society is socializing them to believe that how they look is of vital importance. Bloom may be on to something. How often do you tell a little boy how attractive his outfit is, how nice looking his shoes are, or how handsome he looks today? To support her assertions, Bloom cites, as one example, that about 50 percent of girls ages three to six worry about being fat (Bloom, 2011). We’re talking about kindergarteners who are concerned about their body image. Sociologists are acutely interested in of this type of gender socialization, where societal expectations of how boys and girls should be — how they should behave, what toys and colours they should like, and how important their attire is — are reinforced. One solution to this type of gender socialization is being experimented with at the Egalia preschool in Sweden, where children develop in a genderless environment. All of the children at Egalia are referred to with neutral terms like “friend” instead of he or she. Play areas and toys are consciously set up to eliminate any reinforcement of gender expectations (Haney, 2011). Egalia strives to eliminate all societal gender norms from these children’s preschool world. Extreme? Perhaps. So what is the middle ground? Bloom suggests that we start with simple steps: When introduced to a young girl, ask about her favourite book or what she likes. In short, engage her mind not her outward appearance (Bloom, 2011).

5.2. Why Socialization Matters

Socialization is critical both to individuals and to the societies in which they live. It illustrates how completely intertwined human beings and their social worlds are. First, it is through teaching culture to new members that a society perpetuates itself. If new generations of a society do not learn its way of life, it ceases to exist. Whatever is distinctive about a culture must be transmitted to those who join it in order for a society to survive. For Canadian culture to continue, for example, children in Canada must learn about cultural values related to democracy: They have to learn the norms of voting, as well as how to use material objects such as a ballot. Of course, some would argue that it is just as important in Canadian culture for the younger generation to learn the etiquette of eating in a restaurant or the rituals of tailgate parties before baseball games. In fact, there are many ideas and objects that Canadians teach children in hopes of keeping the society’s way of life going through another generation.

Socialization is just as essential to us as individuals. Social interaction provides the means via which we gradually become able to see ourselves through the eyes of others, learning who we are and how we fit into the world around us. In addition, to function successfully in society, we have to learn the basics of both material and nonmaterial culture, everything from how to dress ourselves to what is suitable attire for a specific occasion; from when we sleep to what we sleep on; and from what is considered appropriate to eat for dinner to how to use the stove to prepare it. Most importantly, we have to learn language — whether it is the dominant language or one common in a subculture, whether it is verbal or through signs — in order to communicate and to think. As we saw with Danielle, without socialization we literally have no self. We are unable to function socially.

Nature versus Nurture

Some experts assert that who we are is a result of nurture — the relationships and caring that surround us. Others argue that who we are is based entirely in genetics. According to this belief, our temperaments, interests, and talents are set before birth. From this perspective, then, who we are depends on nature.

One way that researchers attempt to prove the impact of nature is by studying twins. Some studies followed identical twins who were raised separately. The pairs shared the same genetics, but, in some cases, were socialized in different ways. Instances of this type of situation are rare, but studying the degree to which identical twins raised apart are the same or different can give researchers insight into how our temperaments, preferences, and abilities are shaped by our genetic makeup versus our social environment.

For example, in 1968, twin girls born to a mentally ill mother were put up for adoption. However, they were also separated from each other and raised in different households. The parents, and certainly the babies, did not realize they were one of five pairs of twins who were made subjects of a scientific study (Flam, 2007).

In 2003, the two women, by then age 35, were reunited. Elyse Schein and Paula Bernstein sat together in awe, feeling like they were looking into a mirror. Not only did they look alike, but they behaved alike, using the same hand gestures and facial expressions (Spratling, 2007). Studies like this point to the genetic roots of our temperament and behaviour.

On the other hand, studies of identical twins have difficulty accounting for divergences in the development of inherited diseases. In the case of schizophrenia, epidemiological studies show that there is a strong biological component to the disease. The closer our familial connection to someone with the condition, the more likely we will develop it. However, even if our identical twin develops schizophrenia we are less than 50 percent likely to develop it ourselves. Why is it not 100 percent likely? What occurs to produce the divergence between genetically identical twins (Carey, 2012)?

Though genetics and hormones play an important role in human behaviour, biological explanations of human behaviour have serious deficiencies from a sociological point of view, especially when they are used to try to explain complex aspects of human social life like homosexuality, male aggressiveness, female spatial skills, and the like. As we noted in Chapter 3, the logic of biological explanation usually involves three components: the identification of a supposedly universal quality or trait of human behaviour, an attribution of a genetic source of the behavioural trait, and an argument why this behaviour makes it more likely that the genes that code for it will be passed successfully to descendents. The conclusion of this reasoning is that this behaviour or quality is hard-wired or difficult to change (Lewontin, 1991).

However, an argument, for example that males are naturally aggressive because of their hormonal structure or other biological mechanisms, does not take into account the huge variations in the meaning or practice of aggression between cultures, nor the huge variations in what counts as aggressive in different situations, let alone the fact that many men are not aggressive by any definition, and that men and women both have “male” hormones like testosterone. More interesting for the sociologist in this example is that men who are not aggressive often get called sissies. This indicates that male aggression has to do more with a normative structure within male culture than with a genetic or hormonal structure that explains aggressive behaviour.

Sociology’s larger concern is the effect that society has on human behaviour, the nurture side of the nature versus nurture debate. To what degree are processes of identification and “self-fulfilling prophecy” at work in the lives of the twins Elyse Schein and Paula Bernstein? Despite growing up apart, do they share common racial, class, or religious characteristics? Aside from the environmental or epigenetic factors that lead to the divergence of twins with regard to schizophrenia, what happens to the social standing and social relationships of a person when the condition develops? What happens to schizophrenics in different societies? How does the social role of the schizophrenic integrate him or her into a society (or not)? Whatever the role of genes or biology in our lives, genes are never expressed in a vacuum. Environmental influence always matters.

Making Connections: Case Study

The Life of Chris Langan, the Smartest Man You’ve Never Heard Of

Bouncer. Firefighter. Factory worker. Cowboy. Chris Langan (b. 1952) has spent the majority of his adult life just getting by with jobs like these. He has no college degree, few resources, and a past filled with much disappointment. Chris Langan also has an IQ of over 195, nearly 100 points higher than the average person (Brabham, 2001). So why didn’t Chris become a neurosurgeon, professor, or aeronautical engineer? According to Macolm Gladwell in his book Outliers: The Story of Success (2008), Chris didn’t possess the set of social skills necessary to succeed on such a high level — skills that aren’t innate, but learned.

Gladwell looked to a recent study conducted by sociologist Annette Lareau in which she closely shadowed 12 families from various economic backgrounds and examined their parenting techniques. Parents from lower-income families followed a strategy of “accomplishment of natural growth,” which is to say they let their children develop on their own with a large amount of independence; parents from higher-income families, however, “actively fostered and accessed a child’s talents, opinions, and skills” (Gladwell, 2008). These parents were more likely to engage in analytical conversation, encourage active questioning of the establishment, and foster development of negotiation skills. The parents were also able to introduce their children to a wide range of activities, from sports to music to accelerated academic programs. When one middle class child was denied entry to a gifted and talented program, the mother petitioned the school and arranged additional testing until her daughter was admitted. Lower-income parents, however, were more likely to unquestioningly obey authorities such as school boards. Their children were not being socialized to comfortably confront the system and speak up (Gladwell, 2008).

What does this have to do with Chris Langan, deemed by some as the smartest man in the world (Brabham, 2001)? Chris was born in severe poverty, and he was moved across the country with an abusive and alcoholic stepfather. Chris’s genius went greatly unnoticed. After accepting a full scholarship to Reed College, his funding was revoked after his mother failed to fill out necessary paperwork. Unable to successfully make his case to the administration, Chris, who had received straight A’s the previous semester, was given F’s on his transcript and forced to drop out. After enrolling in Montana State University, an administrator’s refusal to rearrange his class schedule left him unable to find the means necessary to travel the 16 miles to attend classes. What Chris has in brilliance, he lacks in practical intelligence, or what psychologist Robert Sternberg defines as “knowing what to say to whom, knowing when to say it, and knowing how to say it for maximum effect” (Sternberg et al., 2000). Such knowledge was never part of his socialization.

Chris gave up on school and began working an array of blue-collar jobs, pursuing his intellectual interests on the side. Though he’s recently garnered attention from work on his “Cognitive Theoretic Model of the Universe,” he remains weary and resistant of the educational system.

As Gladwell concluded, “He’d had to make his way alone, and no one—not rock stars, not professional athletes, not software billionaires, and not even geniuses—ever makes it alone” (2008).

Individual and Society

How do sociologists explain both the conformity of behaviour in society and the existence of individual uniqueness? The concept of socialization raises a classic problem of sociological analysis: the problem of agency. How is it possible for there to be individual differences, individual choice, or individuality at all if human development is about assuming socially defined roles? How can an individual have agency, the ability to choose and act independently of external constraints? Since Western society places such value on individuality, in being oneself or in resisting peer pressure and other pressures to conform, the question of where society ends and where the individual begins often is foremost in the minds of students of sociology. Numerous debates in the discipline focus on this question.

However, from the point of view emphasized in this chapter, it is a false question. As noted previously, for Mead the individual “agent” already is a “social structure.” No separation exists between the individual and society; the individual is thoroughly social from the inside out and vice versa.

Mead addressed the question of agency at the level of the relationship between the “I” and the “me” as two “phases” that flip back and forth in the life of the self. The “me” is the part of the self in which one recognizes and assumes the expectations or “organized sets of attitudes” of others: our social roles, our designations, our personalities (as they appear to others), and so on. On the basis of the “me” the individual knows what is expected of him or her in a social situation and what the consequences of an action will be. The “I” represents the part of the self which acts or responds to the organized attitudes of others. It is, however, the unpredictable part of the self which embodies the principles of novelty, spontaneity, freedom, initiative (and the possibility of change) in social action because we can never be sure in advance how we will act, nor be certain of the outcome of our actions. “Exactly how we will act never gets into experience until after the action takes place” (Mead, 1934). Both phases are thoroughly social — the individual only ever experiences him- or herself “indirectly” from the standpoint of others — but without the two phases “there could be no conscious responsibility, and there would be nothing novel in experience” (Mead, 1934).

In a similar manner, sociologists argue that individuals vary because the social environments to which they adapt vary. The socialization process occurs in different social environments — i.e., environments made up of the responses of others — each of which impose distinctive and unique requirements. In one family, children are permitted unlimited access to TV and video games; in another, there are no TV or video games, for example. When they are growing up, children adapt and develop different strategies of play and recreation. Their parents and others respond to the child’s choices, either by reinforcing them or encouraging different choices. Along a whole range of social environmental differences and responses, support and resistance, children gradually develop stable and consistent orientations to world, each to some degree unique because each is formed from the vantage point unique to the place in society the child occupies. Individual variation and individual agency are possible because society itself varies in each social situation. Indeed, the configuration of society itself differs according to each individual’s contribution to each social situation.

Sociologists all recognize the importance of socialization for healthy individual and societal development. But how do scholars working in the three major theoretical paradigms approach this topic? Structural functionalists would say that socialization is essential to society, both because it trains members to operate successfully within it and because it perpetuates culture by transmitting it to new generations. Individuals learn and assume different social roles as they age. The roles come with relatively fixed norms and social expectations attached, which allow for predictable interactions between people, but how the individual lives and balances their roles is subject to variation. A critical sociologist might argue that socialization reproduces inequality from generation to generation by conveying different expectations and norms to those with different social characteristics. For example, individuals are socialized with different expectations about their place in society according to their gender, social class, and race. As in the life of Chris Langan, this creates different and unequal opportunities and, therefore, differences between unique individuals. A symbolic interactionist studying socialization is concerned with face-to-face exchanges and symbolic communication. For example, dressing baby boys in blue and baby girls in pink is one small way that messages are conveyed about differences in gender roles. For the symbolic interactionist, though, how these messages are formulated and how they are interpreted are always situational, always renewed, and defined by the specific situations in which the communication occurs.

5.3. Agents of Socialization

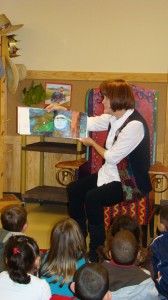

Socialization helps people learn to function successfully in their social worlds. How does the process of socialization occur? How do we learn to use the objects of our society’s material culture? How do we come to adopt the beliefs, values, and norms that represent its nonmaterial culture? This learning takes place through interaction with various agents of socialization, like peer groups and families, plus both formal and informal social institutions.

Social Group Agents

Social groups often provide the first experiences of socialization. Families, and later peer groups, communicate expectations and reinforce norms. People first learn to use the tangible objects of material culture in these settings, as well as being introduced to the beliefs and values of society.

Family

Family is the first agent of socialization. Mothers and fathers, siblings and grandparents, plus members of an extended family all teach a child what he or she needs to know. For example, they show the child how to use objects (such as clothes, computers, eating utensils, books, bikes); how to relate to others (some as “family,” others as “friends,” still others as “strangers” or “teachers” or “neighbours”); and how the world works (what is “real” and what is “imagined”). As you are aware, either from your own experience as a child or your role in helping to raise one, socialization involves teaching and learning about an unending array of objects and ideas.

It is important to keep in mind, however, that families do not socialize children in a vacuum. Many social factors impact how a family raises its children. For example, we can use sociological imagination to recognize that individual behaviours are affected by the historical period in which they take place. Sixty years ago, it would not have been considered especially strict for a father to hit his son with a wooden spoon or a belt if the child misbehaved, but today that same action might be considered child abuse.

Sociologists recognize that race, social class, religion, and other societal factors play an important role in socialization. For example, poor families usually emphasize obedience and conformity when raising their children, while wealthy families emphasize judgment and creativity (National Opinion Research Center, 2008). This may be because working-class parents have less education and more repetitive-task jobs for which the ability to follow rules and to conform helps. Wealthy parents tend to have better education and often work in managerial positions or in careers that require creative problem solving, so they teach their children behaviours that would be beneficial in these positions. This means that children are effectively socialized and raised to take the types of jobs that their parents already have, thus reproducing the class system (Kohn, 1977). Likewise, children are socialized to abide by gender norms, perceptions of race, and class-related behaviours.

In Sweden, for instance, stay-at-home fathers are an accepted part of the social landscape. A government policy provides subsidized time off work — 68 weeks for families with newborns at 80 percent of regular earnings — with the option of 52 of those weeks of paid leave being shared between both mothers and fathers, and eight weeks each in addition allocated for the father and the mother. This encourages fathers to spend at least eight weeks at home with their newborns (Marshall, 2008). As one stay-at-home dad said, being home to take care of his baby son “is a real fatherly thing to do. I think that’s very masculine” (Associated Press, 2011). Overall, 90 percent of Swedish men participate in the paid leave program.

In Canada on the other hand, outside of Quebec, parents can share 35 weeks of paid parental leave at 55 percent of their regular earnings. Only 10 percent of men participate. In Quebec, however, where in addition to 32 weeks of shared parental leave, men also receive five weeks of paid leave, the participation rate of men is 48 percent. In Canada overall, the participation of men in paid parental leave increased from 3 percent in 2000 to 20 percent in 2006 because of the change in law in 2001 that extended the number of combined paid weeks parents could take. Researchers note that a father’s involvement in child raising has a positive effect on the parents’ relationship, the father’s personal growth, and the social, emotional, physical, and cognitive development of children (Marshall, 2008). How will this effect differ in Sweden and Canada as a result of the different nature of their paternal leave policies?

Peer Groups

A peer group is made up of people who are not necessarily friends but who are similar in age and social status and who share interests. Peer group socialization begins in the earliest years, such as when kids on a playground teach younger children the norms about taking turns or the rules of a game or how to shoot a basket. As children grow into teenagers, this process continues. Peer groups are important to adolescents in a new way, as they begin to develop an identity separate from their parents and exert independence. This is often a period of parental-child conflict and rebellion as parental values come into conflict with those of youth peer groups. Peer groups provide their own opportunities for socialization since kids usually engage in different types of activities with their peers than they do with their families. Peer groups provide adolescents’ first major socialization experience outside the realm of their families. They are especially influential, therefore, with respect to preferences in music, style, clothing, etc., sharing common social activities, and learning to engage in romantic relationships. With peers, adolescents experiment with new experiences outside the control of parents: sexual relationships, drug and alcohol use, political stances, hair and clothing choices, and so forth. Interestingly, studies have shown that although friendships rank high in adolescents’ priorities, this is balanced by parental influence. Conflict between parents and teenagers is usually temporary and in the end families exert more influence than peers over educational choices and political, social, and religious attitudes.

Peer groups might be the source of rebellious youth culture, but they can also be understood as agents of social integration. The seemingly spontaneous way that youth in and out of school divide themselves into cliques with varying degrees of status or popularity prepares them for the way the adult world is divided into status groups. The racial characteristics, gender characteristics, intelligence characteristics, and wealth characteristics that lead to being accepted in more or less popular cliques in school are the same characteristics that divide people into status groups in adulthood.

Institutional Agents

The social institutions of our culture also inform our socialization. Formal institutions — like schools, workplaces, and the government — teach people how to behave in and navigate these systems. Other institutions, like the media, contribute to socialization by inundating us with messages about norms and expectations.

School

Most Canadian children spend about seven hours a day and 180 days a year in school, which makes it hard to deny the importance school has on their socialization. In elementary and junior high, compulsory education amounts to over 8,000 hours in the classroom (OECD, 2013). Students are not only in school to study math, reading, science, and other subjects — the manifest function of this system. Schools also serve a latent function in society by socializing children into behaviours like teamwork, following a schedule, and using textbooks.

School and classroom rituals, led by teachers serving as role models and leaders, regularly reinforce what society expects from children. Sociologists describe this aspect of schools as the hidden curriculum, the informal teaching done by schools.

For example, in North America, schools have built a sense of competition into the way grades are awarded and the way teachers evaluate students. Students learn to evaluate themselves within a hierarchical system of A, B, C, etc. students (Bowles & Gintis, 1976). However, different lessons can be taught by different instructional techniques. When children participate in a relay race or a math contest, they learn that there are winners and losers in society. When children are required to work together on a project, they practice teamwork with other people in cooperative situations. Bowles and Gintis argue that the hidden curriculum prepares children for a life of conformity in the adult world. Children learn how to deal with bureaucracy, rules, expectations, to wait their turn, and to sit still for hours during the day. The latent functions of competition, teamwork, classroom discipline, time awareness, and dealing with bureaucracy are features of the hidden curriculum.

Schools also socialize children by teaching them overtly about citizenship and nationalism. In the United States, children are taught to say the Pledge of Allegiance. Most school districts require classes about U.S. history and geography. In Canada, on the other hand, critics complain that students do not learn enough about national history, which undermines the development of a sense of shared national identity (Granatstein, 1998). Textbooks in Canada are also continually scrutinized and revised to update attitudes toward the different cultures in Canada as well as perspectives on historical events; thus, children are socialized to a different national or world history than earlier textbooks may have done. For example, recent textbook editions include information about the mistreatment of First Nations which more accurately reflects those events than in textbooks of the past. In this regard, schools educate students explicitly about aspects of citizenship important for being able to participate in a modern, heterogeneous culture.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

Controversial Textbooks

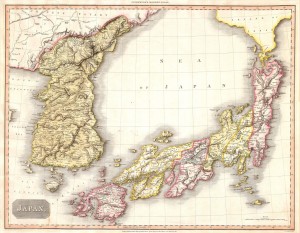

On August 13, 2001, 20 South Korean men gathered in Seoul. Each chopped off one of his own fingers because of textbooks. These men took drastic measures to protest eight middle school textbooks approved by Tokyo for use in Japanese middle schools. According to the Korean government (and other East Asian nations), the textbooks glossed over negative events in Japan’s history at the expense of other Asian countries (The Telegraph, 2001).

In the early 1900s, Japan was one of Asia’s more aggressive nations. Korea was held as a colony by the Japanese between 1910 and 1945. Today, Koreans argue that the Japanese are whitewashing that colonial history through these textbooks. One major criticism is that they do not mention that, during World War II, the Japanese forced Korean women into sexual slavery. The textbooks describe the women as having been “drafted” to work, a euphemism that downplays the brutality of what actually occurred. Some Japanese textbooks dismiss an important Korean independence demonstration in 1919 as a “riot.” In reality, Japanese soldiers attacked peaceful demonstrators, leaving roughly 6,000 dead and 15,000 wounded (Crampton, 2002).

Although it may seem extreme that these people were so enraged about how events are described in a textbook that they would resort to dismemberment, the protest affirms that textbooks are a significant tool of socialization in state-run education systems.

The Workplace

Just as children spend much of their day at school, most Canadian adults at some point invest a significant amount of time at a place of employment. Although socialized into their culture since birth, workers require new socialization into a workplace both in terms of material culture (such as how to operate the copy machine) and nonmaterial culture (such as whether it is okay to speak directly to the boss or how the refrigerator is shared).

Different jobs require different types of socialization. In the past, many people worked a single job until retirement. Today, the trend is to switch jobs at least once a decade. Between the ages of 18 and 44, the average baby boomer of the younger set held 11 different jobs (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010). This means that people must become socialized to, and socialized by, a variety of work environments.

Religion

While some religions may tend toward being an informal institution, this section focuses on practices related to formal institutions. Religion is an important avenue of socialization for many people. Canada is full of synagogues, temples, churches, mosques, and similar religious communities where people gather to worship and learn. Like other institutions, these places teach participants how to interact with the religion’s material culture (like a mezuzah, a prayer rug, or a communion wafer). For some people, important ceremonies related to family structure — like marriage and birth — are connected to religious celebrations. Many of these institutions uphold gender norms and contribute to their enforcement through socialization. From ceremonial rites of passage that reinforce the family unit, to power dynamics which reinforce gender roles, religion fosters a shared set of socialized values that are passed on through society.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

Girls and Movies

Pixar is one of the largest producers of children’s movies in the world and has released large box office draws, such as Toy Story, Cars, The Incredibles, and Up. What Pixar has never before produced is a movie with a female lead role. This changed with Pixar’s movie Brave in 2012. Before Brave, women in Pixar served as supporting characters and love interests. In Up, for example, the only human female character dies within the first ten minutes of the film. For the millions of girls watching Pixar films, there are few strong characters or roles for them to relate to. If they do not see possible versions of themselves, they may come to view women as secondary to the lives of men.

The animated films of Pixar’s parent company, Disney, have many female lead roles. Disney is well known for films with female leads, such as Snow White, Cinderella, The Little Mermaid, and Mulan. Many of Disney’s movies star a female, and she is nearly always a princess figure. If she is not a princess to begin with, she typically ends the movie by marrying a prince or, in the case of Mulan, a military general. Although not all “princesses” in Disney movies play a passive role relative to male characters, they typically find themselves needing to be rescued by a man, and the happy ending they all search for includes marriage.

Alongside this prevalence of princesses, many parents express concern about the culture of princesses that Disney has created. Peggy Orenstein addresses this problem in her popular book, Cinderella Ate My Daughter. Orenstein wonders why every little girl is expected to be a “princess” and why pink has become an all-consuming obsession for many young girls. Another mother wondered what she did wrong when her three-year-old daughter refused to do “non-princessy” things, including running and jumping. The effects of this princess culture can have negative consequences for girls throughout life. An early emphasis on beauty and sexiness can lead to eating disorders, low self-esteem, and risky sexual behaviour among older girls.

What should we expect from Pixar’s Brave, the company’s first film to star a female character? Although Brave features a female lead, she is still a princess. Will this film offer any new type of role model for young girls? (Barnes, 2010; O’Connor, 2011; Rose, 2011).

Government

Although we do not think about it, many of the rites of passage people go through today are based on age norms established by the government. To be defined as an “adult” usually means being 18 years old, the age at which a person becomes legally responsible for themselves. And 65 is the start of “old age” since most people become eligible for senior benefits at that point.

Each time we embark on one of these new categories — adult, taxpayer, senior — we must be socialized into this new role. Seniors, for example, must learn the ropes of obtaining pension benefits. This government program marks the points at which we require socialization into a new category.

Mass Media

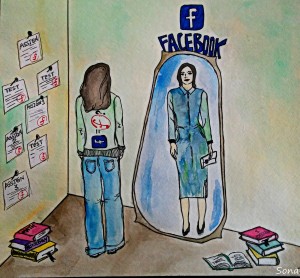

Mass media refers to the distribution of impersonal information to a wide audience via television, newspapers, radio, and the internet. With the average person spending over four hours a day in front of the TV (and children averaging even more screen time), media greatly influences social norms (Roberts, Foehr, & Rideout, 2005; Oliveira, 2013). Statistics Canada reports that for the sample of people they surveyed about their time use in 2010, 73 percent said they watched 2 hours 52 minutes of television on a given day (see the Participants column in Table 5.1 below). Television continues to be the mass medium that occupies the most free time of the average Canadian, but the internet has become the fastest growing mass medium. In the Statistics Canada survey, television use on a given day declined from 77 percent to 73 percent between 1998 and 2010, but computer use increased amongst all age groups from 5 percent to 24 percent and averaged 1 hour 23 minutes on any given day. People who played video games doubled from 3 percent to 6 percent between 1998 and 2010, and the average daily use increased from 1 hour 48 minutes to 2 hours 20 minutes (Statistics Canada, 2013). People learn about objects of material culture (like new technology, transportation, and consumer options), as well as nonmaterial culture—what is true (beliefs), what is important (values), and what is expected (norms).

| Activity group | Population | Participants | Participation rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | |

| hours and minutes | hours and minutes | percentage | |||||||

| 1. Television, reading, and other passive leisure | 02:29 | 02:39 | 02:20 | 03:08 | 03:19 | 02:58 | 79 | 80 | 79 |

| Watching television | 02:06 | 02:17 | 01:55 | 02:52 | 03:03 | 02:41 | 73 | 75 | 71 |

| Reading books, magazines, newspapers | 00:20 | 00:18 | 00:23 | 01:26 | 01:29 | 01:25 | 24 | 20 | 27 |

| Other passive leisure | 00:03 | 00:03 | 00:02 | 01:04 | 01:16 | 00:52 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2. Active leisure | 01:13 | 01:27 | 00:59 | 02:22 | 02:42 | 02:01 | 51 | 54 | 49 |

| Active sports | 00:30 | 00:37 | 00:23 | 01:54 | 02:12 | 01:34 | 26 | 28 | 25 |

| Computer use | 00:20 | 00:23 | 00:17 | 01:23 | 01:32 | 01:14 | 24 | 25 | 23 |

| Video games | 00:09 | 00:14 | 00:04 | 02:20 | 02:40 | 01:38 | 6 | 9 | 4 |

| Other active leisure | 00:14 | 00:13 | 00:15 | 02:05 | 02:06 | 02:04 | 11 | 10 | 12 |

| Note: Average time spent is the average over a 7-day week. Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2010 (Statistics Canada, 2011). Note: this survey asked approximately 15,400 Canadians aged 15 and over to report in a daily journal details of the time they spent on various activities on a given day. Because they were reporting about a given day, the figures sited about the average use of television and other media differ from reports provided by BBM and other groups on the average weekly usage, like the figure of 4 hours per day of TV cited in Roberts, Foehr, and Rideout (2005) above. |

|||||||||

5.4. Socialization Across the Life Course

Socialization isn’t a one-time or even a short-term event. We are not stamped by some socialization machine as we move along a conveyor belt and thereby socialized once and for all. In fact, socialization is a lifelong process. Human development is not simply a product of the biological changes of physical maturation or the cognitive changes of psychological development, but follows a pattern of engaging and disengaging from a succession of roles that does not end with childhood but continues through the course of our lives.

In Canada, socialization throughout the life course is determined greatly by age norms and “time-related rules and regulations” (Setterson, 2002). As we grow older, we encounter age-related transition points that require socialization into a new role, such as becoming school age, entering the workforce, or retiring. At each point in life, as an individual sheds previous roles and assumes new ones, institutions or situations are involved, which requires both learning and revising one’s self-definition: You are no longer living at home; you have a job! You are no longer a child; you in the army! You are no longer single; you are going to have a child! You are no longer free; you are going to jail! You are no longer in mid-life; it is time to retire!

Many of life’s social expectations are made clear and enforced on a cultural level. Through interacting with others and watching others interact, the expectation to fulfill roles becomes clear. While in elementary or middle school, the prospect of having a boyfriend or girlfriend may have been considered undesirable. The socialization that takes place in high school changes the expectation. By observing the excitement and importance attached to dating and relationships within the high school social scene, it quickly becomes apparent that one is now expected not only to be a child and a student, but a significant other as well.

Adolescence in general is a period stretching from puberty to about 18 years old, characterized by the role adjustment from childhood to adulthood. It is a stage of development in which the self is redefined through a more or less arduous process of “socialized anxiety” (Davis, 1944), re-examination and reorientation. As Jean Piaget described it, adolescence is a “decisive turning point … at which the individual rejects, or at least revises his estimate of everything that has been inculcated in him, and acquires a personal point of view and a personal place in life” (1947). It involves a fundamental “growth process” according to Edgar Friedenberg “to define the self through the clarification of experience and to establish self esteem” (1959).

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

Gap Year: How Different Societies Socialize Young Adults

Have you ever heard of a gap year? It’s a common custom in British society. When teens finish their secondary schooling (i.e., high school), they often take a year “off” before entering college. Frequently, they might take a job, travel, or find other ways to experience another culture. Prince William, the Duke of Cambridge, spent his gap year practising survival skills in Belize, teaching English in Chile, and working on a dairy farm in the United Kingdom (Prince of Wales, 2012a). His brother, Prince Harry, advocated for AIDS orphans in Africa and worked as a jackeroo (a novice ranch hand) in Australia (Prince of Wales, 2012b).

In Canada, this life transition point is socialized quite differently, and taking a year off is generally frowned upon. Instead, Canadian youth are encouraged to pick career paths by their mid-teens, to select a university or college and a major by their late teens, and to have completed all university schooling or technical training for their career by their early 20s.

In other nations, this phase of the life course is tied into conscription, a term that describes compulsory military service. Egypt, Austria, Switzerland, Turkey, and Singapore all have this system in place. Youth in these nations (often only males) are expected to undergo a number of months or years of military training and service.

How might your life be different if you lived in one of these countries? Can you think of similar social norms — related to life age-transition points — that vary from country to country?

In some cultures, adolescence is marked and ritualized through a clear rite of passage, a ritual that marks a life cycle transition from a previous status to a new status. Wade Davis described the rite of passage of Algonquin boys of northeastern North America when they hit puberty: Traditionally, the boys were isolated from the rest of the tribe in longhouses for two or three weeks and consumed nothing but a hallucinogenic plant from the datura family (1985). During the long disorienting period of intoxication brought on by the plant the boys would forget what it meant to be a child and learn what it was to be a man.

In modern North American society, the rites of passage are not so clear cut or socially recognized. Already in 1959, Friedenberg argued that the process was hindered because of the pervasiveness of mass media that interfered with the expression of individuality crucial to this stage of life. Nevertheless, North American adolescence provided a similar trial by fire entry into adulthood: “The juvenile era provides the solid earth of life; the security of having stood up for yourself in a tough and tricky situation; the comparative immunity of knowing for yourself just exactly how the actions that must not be mentioned feel…the calm gained from having survived among comrades, that makes one ready to have friends” (Friedenberg, 1959).

Graduation from formal education — high school, vocational school, or college — involves a formal, ceremonial rite of passage yet again and socialization into a new set of expectations. Educational expectations vary not only from culture to culture, but from social class to social class. While middle- or upper-class families may expect their daughter or son to attend a four-year university after graduating from high school, other families may expect their child to immediately begin working full-time, as others within their family may have done before them.

In the process of socialization, adulthood brings a new set of challenges and expectations, as well as new roles to fill. As the aging process moves forward, social roles continue to evolve. Pleasures of youth, such as wild nights out and serial dating, become less acceptable in the eyes of society. Responsibility and commitment are emphasized as pillars of adulthood, and men and women are expected to “settle down.” During this period, many people enter into marriage or a civil union, bring children into their families, and focus on a career path. They become partners or parents instead of students or significant others. Just as young children pretend to be doctors or lawyers, play house, and dress up, adults also engage anticipatory socialization, the preparation for future life roles. Examples would include a couple who cohabitate before marriage, or soon-to-be parents who read infant care books and prepare their home for the new arrival. University students volunteer, take internships, or enter co-op programs to get a taste for work in their chosen careers. As part of anticipatory socialization, adults who are financially able begin planning for their retirement, saving money, and looking into future health care options. The transition into any new life role, despite the social structure that supports it, can be difficult.