Understanding 2SLGBTQ+ Data

Understanding 2SLGBTQ+ Data Standards from Statistics Canada

It is important to accurately and fully understand 2SLGBTQ+ data before analyzing and interpreting it. To assist with this, Statistics Canada has in recent years standardized the way it collects and reports data on gender and sexual orientation. These developments in standardization matter for social work educators, because they shape the evidence we rely on to teach about areas such as 2SLGBTQ+ health, well-being, and social inclusion in Canada.

First, it is important to understand what is a statistical standard. Most simply, a statistical standard is a set of rules about how data is collected on a particular topic and how statistics are produced and published. In other words, standards specify how questions in nationally representative surveys are asked as well as the way statistics are disseminated. These standards help those using the data accurately interpret and understand it. By ensuring questions are asked the same way with each subsequent wave or survey year, statistical standards also help ensure data comparability over time which facilitates tracking changes in socio-demographic and economic conditions.

As an example, if social workers wish to determine the proportion of transgender people living in the Canadian population, they would read about sex at birth and gender standards as established by Statistics Canada. Now, let’s look at three standards which are essential for capturing and disseminating data about 2SLGBTQ+ people in Canada.

Gender of Person

Since 2021, Statistics Canada has applied a new gender variable across its surveys. Respondents are asked about their current gender, not simply their sex at birth. This change recognizes that sex assigned at birth and gender identity are not the same. The standard allows people to identify as male, female, or another gender (with write-in options), and it can be combined with the sex-at-birth question to identify transgender and non-binary populations. Social work educators can therefore point students to national data that accurately reflects gender diversity and provide examples of how the social work profession can move beyond binary frameworks in their own practice.

Gender of Person Definition and Usage (Statistics Canada)

Gender of Person Reference Guide (Statistics Canada)

Watch CTV news report for the 2021 Canada Census adding gender identity, here.

Sex at Birth

The sex-at-birth variable refers to the sex assigned at birth, typically recorded on a person’s birth certificate and based on physical characteristics such as reproductive system, chromosomes, and genitals. It is distinct from gender, though the two are interrelated. For many people, their sex at birth and their gender are the same. For others, including many transgender and non-binary people, their gender does not align with their sex at birth.

Statistics Canada introduced this standard in 2021 to align with federal policy which updated sex and gender information. When paired with the gender variable, sex at birth allows researchers to identify and estimate transgender and gender-diverse populations in national surveys. This combined approach is especially important for health, demographic, and social indicators where disparities between cisgender and transgender Canadians are important to understand.

The standard recognizes three classification categories: male, female, and intersex. Information can be self-reported or reported by proxy, depending on the survey. Because the populations are small, caution is required when reporting results to avoid disclosure risks and to respect privacy.

For social work education, understanding this variable helps students appreciate both the ethical safeguards in national data collection and the methodological importance of measuring sex at birth alongside gender to produce more inclusive and accurate evidence.

Sexual Orientation

Statistics Canada also uses a standardized variable for sexual orientation. Respondents are asked how they identify, with options such as heterosexual, gay or lesbian, bisexual, and “another sexual orientation” with space to self-identify. While this measure is limited to identity (and does not consistently capture attraction or behaviour), it represents a critical step in creating comparable estimates across surveys. For social work education, this allows us to highlight both the progress and the gaps. In other words, now have nationally representative statistics for 2SLGBTQ+ populations, but we must also acknowledge that lived experiences may not always align neatly with identity labels.

These standards mean that when we use Statistics Canada survey data we have clearer, more inclusive set of measures. This provides a foundation for teaching students about how national data can both illuminate and obscure 2SLGBTQ+ lived experiences. On the one hand, we can chart disparities in health, housing, or social inclusion. On the other hand, we need to remind students that data categories are inherently imperfect and shaped by institutional choices about what—and who—gets measured.

See Gender, sex at birth, sexual orientation, and related standards by variable for related definitions.

Community-Based Surveys and Nuanced Measures

While national statistical standards provide consistency and comparability, they often cannot capture the full range of identities and experiences within 2SLGBTQ+ communities. Community-driven projects such as Trans PULSE Canada demonstrate how survey design can become more inclusive when informed directly by the populations being studied.

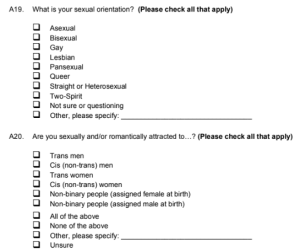

For example, Trans PULSE Canada asks multiple overlapping questions about sexual orientation (e.g., asexual, pansexual, queer, Two-Spirit, questioning) and includes a separate measure of sexual and romantic attration (e.g., attraction to cisgender men, transgender women, non-binary people). These distinctions recognize that identity and attraction do not always align and allow for a richer understanding of lived experiences.

Figure 1. Sample Sexual Orientation and Attraction Questions from Trans PULSE Canada (2020)

In contrast, Statistics Canada’s standardized questions on sexual orientation focus mainly on identity labels such as heterosexual, gay or lesbian, and bisexual. These measures create comparability at a national level but miss identities outside these categories or the complexities of attraction and behavior.

For social work education, the contrast highlights an important methodological lesson: how questions are asked directly affects who is counted, which inequities are visible, and what interventions can be justified in policy and programming. In other words, national surveys help in understanding larger patterns and policy-relevant statistics, while community-based surveys reveal the nuance needed to understand lived realities and guide responsive, inclusive practice.

Levels of Data

Microdata

In line with the scope of this OER, this section focuses on quantitative, numeric data. Data exists on a continuum from the most detailed (“raw” responses) to summarized forms. When data is first collected, it exists at the unit of observation (e.g., each person, household, or organization surveyed). In practical terms, this means that each row in a dataset represents one unit of observation and their answers to survey questions. For example, in a health survey, each row might represent a person, while each column represents a variable (a specific question asked, such as age, gender, or self-rated health).

This disaggregated level of data is called microdata. Microdata is well suited for statistical analysis and often consists of thousands of rows (cases) and hundreds of columns (variables). There are two main types of microdata products available in Canada. First, Public Use Microdata Files (PUMFs) are freely available to the public through Statistics Canada’s Rich Data Services (RDS) platform. In Ontario universities, students can also access PUMFs through their academic libraries via the ODESI system, which additionally provides access to some aggregate data products such as Canadian public opinion polls. Because PUMFs are anonymized to prevent disclosure risks, they usually contain fewer variables and less geographic detail than the original files. However, PUMFs remain very useful for teaching, training, course assignments, and in many cases for thesis or faculty research.

Second, for access to more detailed information, students, faculty, and (at cost) community researchers can apply for secure access to Masterfile microdata through the Statistics Canada Research Data Centres (RDC) program. Masterfiles retain the full range of variables and geographic detail, making them far richer for advanced research, but access requires a formal application (including security clearance) and adherence to strict confidentiality protocols. Applications for access to secure Masterfile microdata can be submitted through Statistics Canada’s Microdata Access Portal. To explore surveys and variables in surveys, see the Canadian Research Data Centre Network site.

Aggregate Data

Post data collection, these individual-level responses can be grouped together into larger categories—such as age groups, provinces, or rural/urban location—producing what is known as aggregate data. Aggregate data presents information in summarized form, making it easier to interpret while also protecting individual participants’ confidentiality. Instead of displaying each individual’s response, aggregate data tables present group-level information such as the number of 2SLGBTQ+ people living in census metropolitan areas, or the household composition of same-sex couples. Aggregate data is the form most often published openly on websites such as the Statistics Canada website, federal or provincial open data portals, and by community organizations.

Statistical Information

From aggregate data, statistical information is derived. Statistical information refers to the measures calculated to describe or compare populations, such as percentages, averages, medians, or rates. For example, aggregate data might be used to calculate the percentage of Canadians aged 15–24 who identify as 2SLGBTQ+, the average household income of same-sex couples, or the rate of suicide attempts among 2SLGBTQ+ youth compared to their non-2SLGBTQ+ peers. These statistical summaries are easier to interpret and communicate, and they can be incorporated into infographics, reports, and other clear formats that support effective knowledge sharing.

For social workers, both aggregate data and the statistical information that is derived from it are often the most accessible forms of evidence. They are used to understand the socio-demographic composition of communities, identify social and health service gaps, and track patterns of inequality. For example, aggregate statistics on mental health outcomes for 2SLGBTQ+ youth can help social workers design targeted programs in key geographic areas, while census data on household composition can support funding proposals for housing or family services. For policy advocacy, statistical information provides credible evidence to argue for resource allocation or legislative change. For example, when Statistics Canada’s 2021 Census reported that 1 in 300 Canadians aged 15 and older identified as transgender or non-binary, advocacy groups used this information to highlight the need for inclusive health care, gender-affirming services, and stronger anti-discrimination protections across Canada.

Much aggregate data and statistical information are publicly available through open data licenses on the Statistics Canada website. However, no statistical agency can anticipate every combination of variables that social workers might need. If the exact information is not available in published tables, this does not necessarily mean the data do not exist; rather, the data may need to be compiled differently. In such cases, Statistics Canada offers custom tabulations (for a fee), which can generate tailored summaries to meet specific research or practice needs. For example, while published tables may show the percentage of 2SLGBTQ+ people by age group or by urban/rural location, a social worker might need a cross-tabulation that links 2SLGBTQ+ identity with both rural residence and household income to better understand service gaps in rural low-income communities.

While it is necessary to limit the scope of this OER to quantitative data at this time, social workers should remain mindful of the limitations of aggregate data and statistical information, recognizing that behind every statistic are lived experiences that may not be fully captured in summarized numbers.

Metadata Standards

In addition to statistical standards used in surveys, social workers should also be aware of metadata standards. Metadata refers to the structured information that describes, organizes, and makes resources discoverable in library catalogues, archives, and databases. Just as survey standards shape how populations are counted, metadata standards shape how knowledge can be searched and found.

One example is the Homosaurus, an international linked data vocabulary of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and Two-Spirit (2SLGBTQ2+) terms. Because Homosaurus is community-driven, it can better reflect lived experiences. Homosaurus provides standardized subject headings that libraries, archives, and digital repositories use to describe 2SLGBTQ+-related materials. For instance, terms such as gender-affirming care, nonbinary people, or Two-Spirit identity are included to ensure more inclusive and consistent cataloguing than traditional library systems alone (e.g., Library of Congress Subject Headings).