29 5.4 Memory Techniques

Many students complain that they can’t remember necessary material. They say they understand the content when they read it, but can’t recall it later. There is a difference between understanding and remembering. You may understand all the systems of the human body (they make sense when you read about them), but that doesn’t mean you’ll be able to recall the necessary terms. Fortunately there are memory techniques and strategies for you to use. Some will be more useful for some subjects and content than others.

As you identify the content you are working to learn, you will often discover things that you will need to commit to memory. There are numerous strategies that will help you to remember important information effectively so that you can recall it on tests, apply it to subsequent courses, and use it throughout your life and career.

What is memory? Memory is the ability to remember past experiences, and a record of the learning process. The human brain has the ability, known as neuroplasticity, that allows it to form new neural pathways, alter existing connections, and adapt and react in ever-changing ways as we learn. Information must go into our long term memory and then, to retrieve it from our memory, we must have a way of getting it back.

Long-term memory stores all the significant events that mark our lives; it lets us retain the meanings of words and the physical skills that we have learned. There are three steps involved in establishing a long term memory: encoding, storage, and retrieval.

- To encode, you assign meaning to the information.

- To store information, you review it and its meanings (study), as repetition is essential to remembering.

- To retrieve it, you follow the path you created through encoding. This may include a number of memory triggers that you used when you were encoding.

An Information Processing Model

Once information has been encoded, we have to retain it. Our brains take the encoded information and place it in storage. Storage is the creation of a permanent record of information.

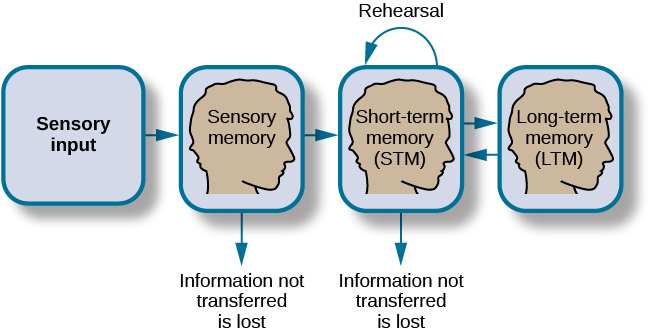

In order for a memory to go into storage (i.e. long-term memory), it has to pass through three distinct stages: Sensory Memory, Short-Term Memory, and finally Long-Term Memory. These stages were first proposed by Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968). Their model of human memory is based on the belief that we process memories in the same way that a computer processes information.

Learning, Remembering, and Retrieving Information

The first thing our brains do is to take in information from our senses (what we see, hear, taste, touch and smell). In many classroom and homework settings, we primarily use hearing for lectures and seeing for reading textbooks. Information we perceive from our senses is stored in what we call the short-term memory.

It is useful to then be able to do multiple things with information in the short-term memory. We want to: 1) decide if that information is important; 2) for the information that is important, be able to save the information in our brain on a longer-term basis—this storage is called the long-term memory; 3) retrieve that information when we need to. Exams often measure how effectively the student can retrieve “important information.”

In some classes and with some textbooks it is easy to determine information important to memorize. In other courses with other textbooks, that process may be more difficult. Your instructor can be a valuable resource to assist with determining the information that needs to be memorized. Once the important information is identified, it is helpful to organize it in a way that will help you best understand.

Moving Information from the Short-term Memory to the Long-term Memory

This is something that takes a lot of time: there is no shortcut for it. Students who skip putting in the time and work often end up cramming at the end.

Once information is memorized, regardless of when the exam is, the last step is to apply the information. Ask yourself: In what real world scenarios could you apply this information? And for mastery, try to teach the information to someone else.

How we save information to our long-term memory has a lot to do with our ability to retrieve it when we need it at a later date. Our mind “saves” information by creating a complex series of links to the data. The stronger the links, the easier it is to recall. You can strengthen these links by using the following strategies. You should note how closely they are tied to good listening and note-taking strategies.

- Make a deliberate decision to remember the specific data. “I need to remember Richard’s name” creates stronger links than just wishing you had a better memory for names.

- Link the information to your everyday life. Ask yourself, “Why is it important that I remember this material?”—and answer it.

- Link the information to other information you already have “stored”, especially the key themes of the course, and you will recall the data more easily. Ask yourself how this is related to other information you have. Look for ways to tie items together. Are they used in similar ways? Do they have similar meanings? Do they sound alike?

- Mentally group similar individual items into “buckets.” By doing this, you are creating links, for example, among terms to be memorized. For example, if you have to memorize a vocabulary list for a Spanish class, group the nouns together with other nouns, verbs with verbs, and so forth. Or your groupings might be sentences using the vocabulary words.

- Use visual imagery. Picture the concept vividly in your mind. Make those images big, bold, and colourful—even silly! Pile concepts on top of each other or around each other; exaggerate their features like a caricature; let your imagination run wild. Humor and crazy imagery can help you recall key concepts.

- Use the information. Studies have generally shown that we retain only 5 percent of what we hear, 10 percent of what we read, 20 percent of what we learn from multimedia, and 30 percent of what is demonstrated to us, but we do retain 50 percent of what we discuss, 75 percent of what we practice by doing, and 90 percent of what we teach others or use immediately in a relevant activity. Review your notes, participate in class, and study with others.

- Break information down into manageable “chunks.” Memorizing the ten-digit number “3141592654” seems difficult, but breaking it down into two sets of three digits and one of four digits, like a phone number—(314) 159-2654—now makes it easier to remember. (Pat yourself on the back if you recognized that series of digits: with a decimal point after the three, that’s the value of pi to ten digits. Remember your last math class?)

- Work from general information to the specific. People usually learn best when they get the big picture first, and then look at the details.

- Eliminate distractions. Every time you have to “reboot” your short-term memory, you risk losing data points. Multi-tasking—listening to music or chatting on Facebook while you study—will play havoc with your ability to memorize because you will need to reboot your short-term memory each time you switch mental tasks.

- Repeat, repeat, repeat. Hear the information; read the information; say it (yes, out loud), and say it again. The more you use or repeat the information, the stronger the links to it. The more senses you use to process the information, the stronger the memorization. Write information on index cards to make flash cards and use downtime (when waiting for the subway or during a break between classes) to review key information.

- This is a test. Test your memory often. Try to write down everything you know about a specific subject, from memory. Then go back and check your notes and textbook to see how you did. Practicing retrieval in this way helps ensure long-term learning of facts and concepts.

- Location, location, location. There is often a strong connection between information and the place where you first received that information. Associate information to learning locations for stronger memory links. Picture where you were sitting in the lecture hall as you repeat the facts in your mind.

Exercise: Just for Fun

Exercise: Test Your Memory

Read the following list for about twenty seconds. After you have read it, cover it and write down all the items you remember.

- Arch

- Chowder

- Airplane

- Kirk

- Paper clip

- Column

- Oak

- Subway

- Leia

- Fries

- Pen

- Maple

- Window

- Scotty

- Thumb drive

- Brownies

- Door

- Skateboard

- Cedar

- Luke

How many were you able to recall? Most people can remember only a fraction of the items.

Now read the following list for about twenty seconds, cover it, and see how many you remember.

- Fries

- Chowder

- Brownies

- Paper clip

- Pen

- Thumb drive

- Oak

- Cedar

- Maple

- Airplane

- Skateboard

- Subway

- Luke

- Leia

- Kirk

- Scotty

- Column

- Window

- Door

- Arch

Did your recall improve? Why do you think you did better? Was it easier? Most people take much less time doing this version of the list and remember almost all the terms. The list is the same as the first list, but the words have now been grouped into categories. Use this grouping method to help you remember lists of mixed words or ideas.

Using Flashcards

Flash cards are a valuable tool for memorization because they allow students to be able to test themselves. They are convenient to bring with you anywhere, and can be used effectively whether a student has one minute or an hour. Create your own flash cards using index cards, writing the questions on one side and the answers on the other. Creating the flash cards help with memory because you need to decide what is important to put on the cards, summarize key principles, and the act of writing it down helps too. Then you can use them to review and/or test yourself repeatedly. You can use them almost anywhere. For example, you can pull out the flash cards on the bus and test yourself during your commute.

Using Mnemonics

What do the names of the Great Lakes, the makings of a Big Mac, and the number of days in a month have in common? They are easily remembered by using mnemonic devices. Mnemonics (pronounced neh-MA-nicks) are tricks for memorizing lists and data. They create artificial but strong links to the data, making recall easier. The most commonly used mnemonic devices are acronyms, acrostics, rhymes, and jingles.

Acronyms are words or phrases made up by using the first letter of each word in a list or phrase. Need to remember the names of the Great Lakes? Try the acronym HOMES using the first letter of each lake:

- Huron

- Ontario

- Michigan

- Erie

- Superior

To create an acronym, first write down the first letters of each term you need to memorize. Then rearrange the letters to create a word or words. You can find acronym generators online (just search for “acronym generator”) that can help you by offering options. Organizing information in this way can be helpful because it is not as difficult to memorize the acronym, and with practice and repetition, the acronym can trigger the brain to recall the entire piece of information. Acronyms work best when your list of letters includes vowels as well as consonants and when the order of the terms is not important. If no vowels are available, or if the list should be learned in a particular order, try using an acrostic instead.

Acrostics are similar to acronyms in that they work off the first letter of each word in a list. But rather than using them to form a word, the letters are represented by entire words in a sentence or phrase. If you’ve studied music, you may be familiar with “Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge” to learn the names of the notes on the lines of the musical staff: E, G, B, D, F. The ridiculous and therefore memorable line “My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nine Pizzas” was used by many of us to remember the names of the planets (at least until Pluto was downgraded):

| My | Mercury |

| Very | Venus |

| Educated | Earth |

| Mother | Mars |

| Just | Jupiter |

| Served | Saturn |

| Us | Uranus |

| Nine | Neptune |

| Pizzas | Pluto |

To create an acrostic, list the first letters of the terms to be memorized in the order in which you want to learn them (like the planet names). Then create a sentence or phrase using words that start with those letters.

Rhymes are short verses used to remember data. A common example is “In fourteen hundred and ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” Need to remember how many days a given month has? “Thirty days hath September, April, June, and November…,” and so forth. Writing rhymes is a talent that can be developed with practice. To start, keep your rhymes short and simple. Define the key information you want to remember and break it down into a series of short phrases. Look at the last words of the phrases: can you rhyme any of them? If they don’t rhyme, can you substitute or add a word to create the rhyme? (For example, in the Columbus rhyme, “ninety-two” does not rhyme with “ocean,” but adding the word “blue” completes the rhyme and creates the mnemonic.)

Jingles are phrases set to music, so that the music helps trigger your memory. Jingles are commonly used by advertisers to get you to remember their product or product features. Remember “Two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions on a sesame seed bun”—the original Big Mac commercial. Anytime you add rhythm to the terms you want to memorize, you are activating your auditory sense, and the more senses you use for memorization, the stronger the links to the data you are creating in your mind. To create a jingle for your data, start with a familiar tune and try to create alternate lyrics using the terms you want to memorize. Another approach you may want to try is reading your data aloud in a hip-hop or rap music style. The late Velma McKay, a former math instructor at College of the Rockies, was well known for singing to her students. She replaced the lyrics to many familiar songs and sang them in class to help them remember important math formulas. Imagine singing the quadratic formula to the tune of “London Bridge is Falling Down”.

Exercise: Creative Memory Challenge

Create an acrostic to remember the noble gasses: helium (He), neon (Ne), argon (Ar), krypton (Kr), xenon (Xe), and the radioactive radon (Rn).

Create an acronym to remember the names of the G8 group of countries: France, the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia, Germany, Japan, Italy, and Canada. (Hint: Sometimes it helps to substitute terms with synonyms—“America” for the United States or “England” for the United Kingdom—to get additional options.)

Create a jingle to remember the names of the Seven Dwarfs: Bashful, Doc, Dopey, Grumpy, Happy, Sleepy, and Sneezy.

Mnemonics are good memory aids, but they aren’t perfect. They take a lot of effort to develop, and they also take terms out of context because they don’t focus on the meaning of the words. Since they lack meaning, they can also be easily forgotten later on, although you may remember them through the course.

Exercise: Memory Quiz

For each of the following statements, circle T for true or F for false

| Flash cards provide convenient tools to review and test memory. | T | F |

| Multi-tasking enhances your active memory. | T | F |

| If you listen carefully, you will remember most of what was said for three days. | T | F |

| “Use it or lose it” applies to information you want to remember. | T | F |

| Mnemonics should be applied whenever possible. | T | F |

| Type | Sample Method |

|---|---|

| Acronyms | Every discipline has its own language and acronyms are the abbreviations. Acronyms can be used to remember words in sequence or a group of words representing things or concepts. CAD can mean: Control Alt Delete, Canadian Dollar, Computer Aided Design, Coronary Artery Disease, Canadian Association of the Deaf, Crank Angle Degree, etc. |

| Acrostics | Acrostics are phrases where the first letter of each word represents another word. They are relatively easy to make and can be very useful for remembering groups of words. For example: King Philip Can Only Find His Green Slippers. This is the classification system of Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species. |

| Chunking | You can capitalize on your short term memory by “chunking” information. If you need to remember this number: 178206781. The task would exhaust your seven units of storage space unless you “chunk” the digits into groups. In this case, you could divide it into three chunks, like a social insurance number: 178 206 781. By chunking the information and repeating it you can stretch the capacity of your short term memory. |

| Flash cards | Flash cards provide a convenient tool to test yourself frequently. You can purchase flash cards for common memory tasks such as learning multiplication tables, or you can create your own for learning facts, systems, and processes. |

| Images | This helps us remember by linking words to meanings through associations based on how a word sounds and creating imagery for specific words. This sort of visualization was found to be more effective when one listened to someone reading a text than when they read the text themselves. |

| Jingle | Jingles or short songs are great tools for memory. Remember the famous song to teach children parts of the body, “Head and shoulders, knees and toes, knees and toes, knees and toes. Head and shoulders, knees and toes. Eyes, ears, mouth and nose.” |

| Locations and Journeys | Traditionally known as the Method of Loci, we associate each word from a list or grouping with a location. Imagine a place with which you are familiar, such as, the rooms in your house. These become the objects of information you need to memorize. Another example is to use the route to your work or school, with landmarks along the way becoming the information you need to memorize. When you do this in order of your journey through the imagined space, it makes it easier to retrieve all of the information in the future. |

| Maps & Diagrams | Graphic organizers help us remember by connecting new information to our existing knowledge and to let us see how concepts relate to each other and fit into a context. Mind and concept maps, Cause and Effect, Fishbone, Cycle, Flow Chart, Ladders, Story Board, Compare and Contrast, Venn Diagrams, and more. |

| Reciting | Saying something out loud activates more areas of our brain and helps to connect information to other activities. |

| Rhymes | Rhyme, rhythm, repetition, and melody make use of our brain’s ability to encode audio information and use patterns to aid memory. They help recall by limiting the possible options to those items that fit the pattern you have created. |

| Summarizing | This traditional element of note taking is a way to physically encode materials that make it easier for our brain to store and retrieve. It can be said that if we cannot summarize, then we have not learned…yet. |

Exercise: Try it

Select one course where memorizing key concepts is a part of your exam preparation. Choose at least one new strategy from the chart above this week. Monitor—is this strategy effective for what you are trying to learn? A good way to monitor is to see if you can recall the information accurately without looking at a text or notes.

Key Takeaways

- Moving information from sensory memory to short-term memory to long-term memory and being able to retrieve it requires repetition and strategies.

- To keep information in our memory, we must use it or build links with it to strengthen it in long-term memory.

- Key ways to remember information include linking it to other information already known; organizing facts in groups of information; eliminating distractions; and repeating the information by hearing, reading, and saying it aloud.

- To remember specific pieces of information, try creating a mnemonic that associates the information with an acronym or acrostic, a rhyme or a jingle.

- There are numerous memory strategies listed and it’s wise to try them and see which ones work best for you.

Image Long Description

Atkinson-Shiffrin model of memory: Sensory input leads to sensory memory. Information not transferred is lost. Sensory memory leads to short-term memory. Information not transferred is lost. Information that is rehearsed may remain in short-term memory. Short term memory leads to long-term memory. [Return to image]

Text Attributions

- The first five paragraphs, Table 5.4.1, and “Try it” were adapted from “Master Your Memory” in University 101: Study, Strategize and Succeed by Kwantlen Polytechnic University. Adapted by Mary Shier. CC BY-SA.

- Text under “An Information Processing Model” has been adapted from “Memory” in Blueprint for Success in College and Career by Phyllis Nissila and David Dillon. Adapted by Mary Shier. CC BY.

- Text under “Moving Information from the Short-term Memory To the Long-term Memory,” “Using Mnemonics,” Creative Memory Challenge, and Key Takeaways has been adapted from “Remembering Course Materials” in University Success by N. Mahoney, B. Klassen, and M. D’Eon. Adapted by Mary Shier. CC BY-NC-SA.