Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Discuss the vertebral column and regional variations in its bony components and curvatures

- Describe each region of the vertebral column and the number of bones in each region

- Describe the distinguishing characteristics for vertebrae in each vertebral region and features of the sacrum and the coccyx

- Define the structure of an intervertebral disc

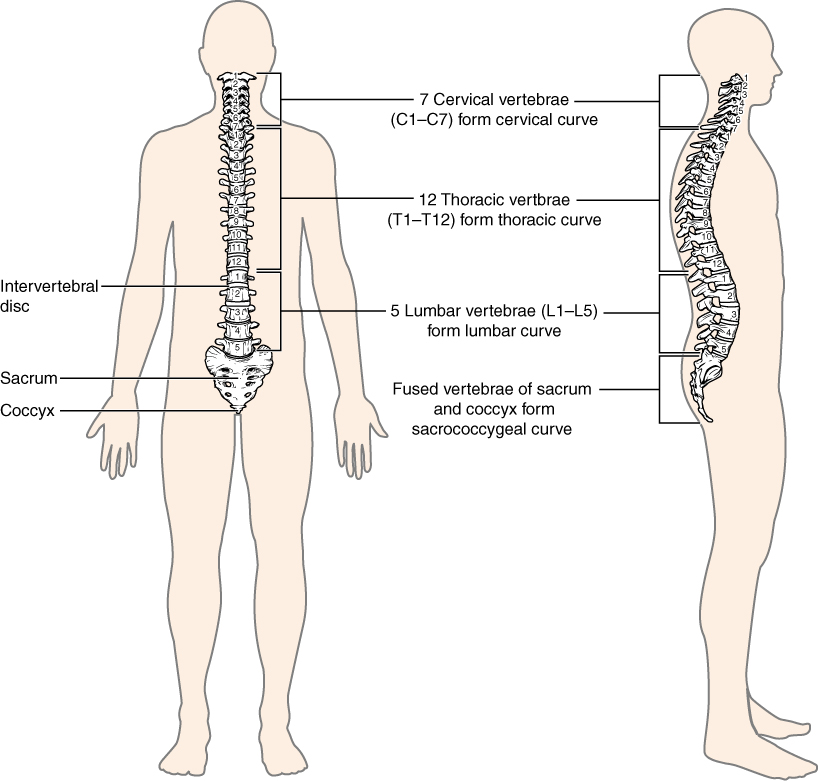

The vertebral column is also known as the spinal column (Figure 7.4.1). It consists of a sequence of vertebrae (singular = vertebra), each of which is separated and united by a cartilaginous intervertebral disc. Together, the vertebrae and intervertebral discs form the vertebral column. It is a flexible column that supports the head, neck, and body and allows for their movements. It also protects the spinal cord, which passes through openings in the vertebrae.

Regions of the Vertebral Column

The vertebral column originally develops as a series of 33 vertebrae, but this number is eventually reduced to 24 vertebrae, plus the fused vertebrae comprising the sacrum and coccyx. The vertebral column is subdivided into five regions, with the vertebrae in each area named for that region and numbered in descending order. In the neck, there are seven cervical vertebrae, each designated with the letter “C” followed by its number. Superiorly, the C1 vertebra articulates (forms a joint) with the occipital condyles of the skull. Inferiorly, C1 articulates with the C2 vertebra, and so on. Below these are the 12 thoracic vertebrae, designated T1–T12. The lower back contains the L1–L5 lumbar vertebrae. The sacrum, which is also part of the pelvis, is formed by the fusion of five sacral vertebrae, though in about 33% percent of the population T12 is fused to the sacrum or S1 remains unfused. This is called transitional anatomy. Similarly, the coccyx, or tailbone, results from the fusion of four small coccygeal vertebrae. However, the sacral and coccygeal fusions do not start until age 20 and are not completed until middle age.

An interesting anatomical fact is that almost all mammals have seven cervical vertebrae, regardless of body size. This means that there are large variations in the size of cervical vertebrae, ranging from the very small cervical vertebrae of a shrew to the greatly elongated vertebrae in the neck of a giraffe. In a full-grown giraffe, each cervical vertebra is 11 inches tall.

Curvatures of the Vertebral Column

The adult vertebral column does not form a straight line, but instead has four curvatures along its length (see Figure 7.4.1). These curves increase the vertebral column’s strength, flexibility, and ability to absorb shock. When the load on the spine is increased, by carrying a heavy backpack for example, the curvatures increase in depth (become more curved) to accommodate the extra weight. They then spring back when the weight is removed. The four adult curvatures are classified as either primary or secondary curvatures. Primary curvatures are retained from the original fetal curvature, while secondary curvatures develop after birth.

During fetal development, the body is flexed anteriorly into the fetal position, giving the entire vertebral column a single curvature that is concave anteriorly. In the adult, this primary curvature is retained in two regions of the vertebral column as the thoracic curve, which involves the thoracic vertebrae, and the sacrococcygeal curve, formed by the sacrum and coccyx.

A secondary curve develops gradually after birth as the child learns to sit upright, stand, and walk. Secondary curves are concave posteriorly, opposite in direction to the original fetal curvature. The cervical curve of the neck region develops as the infant begins to hold their head upright when sitting. Later, as the child begins to stand and then to walk, the lumbar curve of the lower back develops. In adults, the lumbar curve is generally deeper in females.

General Structure of a Vertebra

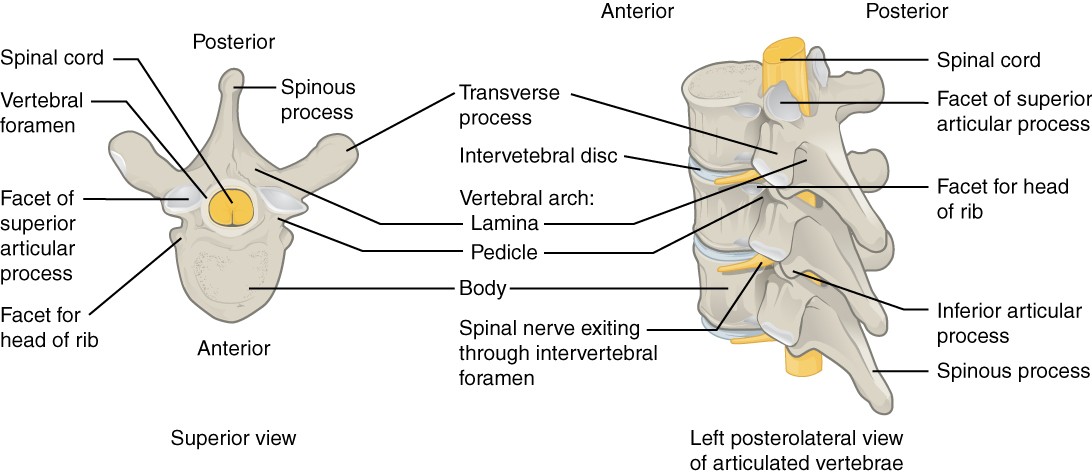

Within the different regions of the vertebral column, vertebrae vary in size and shape, but they all follow a similar structural pattern. A typical vertebra will consist of a body, a vertebral arch, and seven processes (Figure 7.4.4).

The body is the anterior portion of each vertebra and is the part that supports the body weight. Because of this, the vertebral bodies progressively increase in size and thickness going down the vertebral column. The bodies of adjacent vertebrae are separated and strongly united by an intervertebral disc.

When the vertebrae are aligned together in the vertebral column, notches in the margins of the pedicles of adjacent vertebrae together form an intervertebral foramen, the opening through which a spinal nerve exits from the vertebral column (Figure 7.4.5).

Regional Modifications of Vertebrae

In addition to the general characteristics of a typical vertebra described above, vertebrae also display characteristic size and structural features that vary between the different vertebral column regions. Thus, cervical vertebrae are smaller than lumbar vertebrae due to differences in the proportion of body weight that each supports. Thoracic vertebrae have sites for rib attachment, and the vertebrae that give rise to the sacrum and coccyx are fused together into single bones.

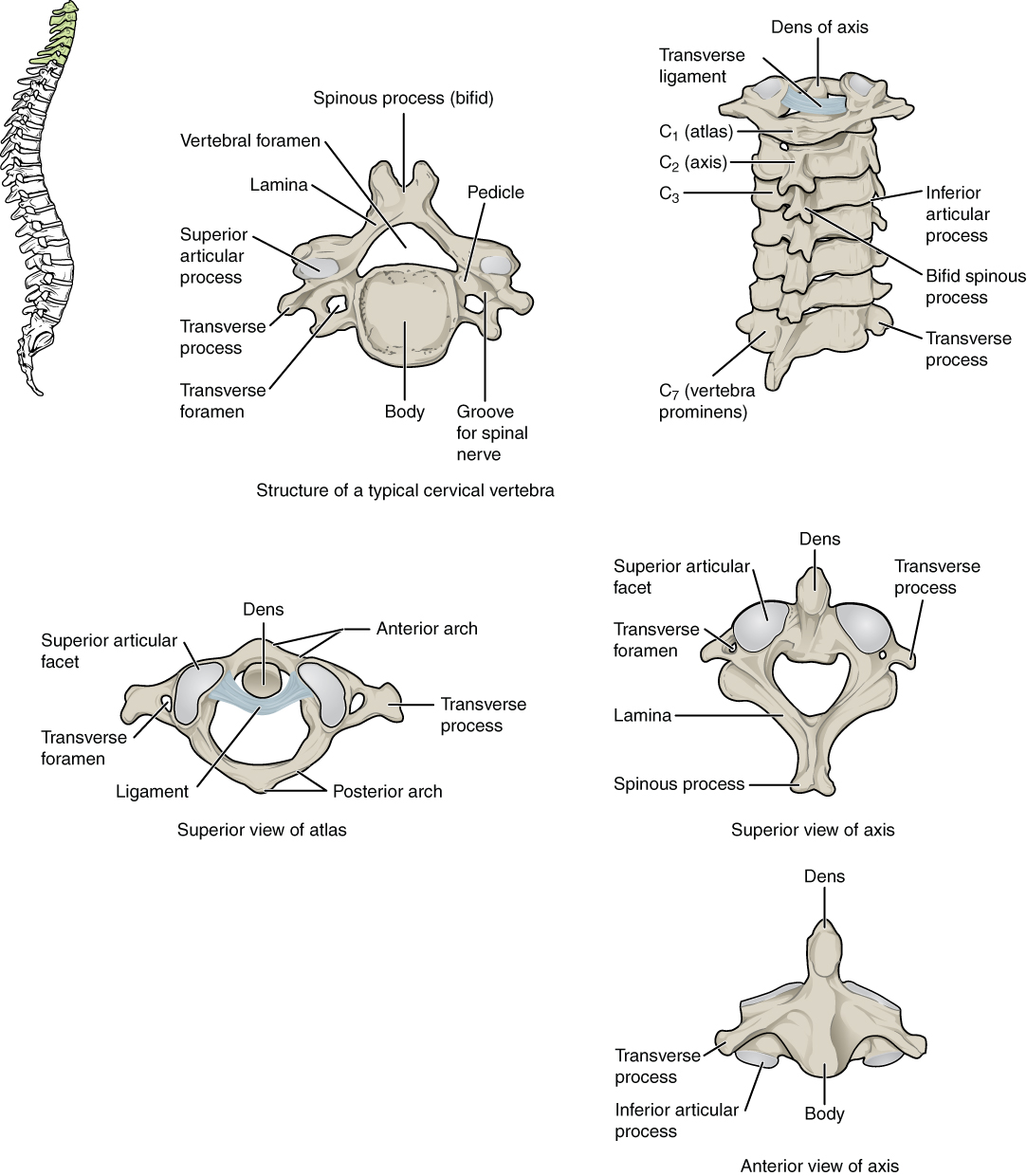

Cervical Vertebrae

Typical cervical vertebrae, such as C4 or C5, have several characteristic features that differentiate them from thoracic or lumbar vertebrae (Figure 7.4.6). Cervical vertebrae have a small body, reflecting the fact that they carry the least amount of body weight. You can find these vertebrae by running your finger down the midline of the posterior neck until you encounter the prominent C7 spine located at the base of the neck. The transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae are sharply curved (U-shaped) to allow for passage of the cervical spinal nerves. Each transverse process also has an opening called the transverse foramen. The vertebral arteries that supply the brain ascends up the neck by passing through these openings.

Thoracic Vertebrae

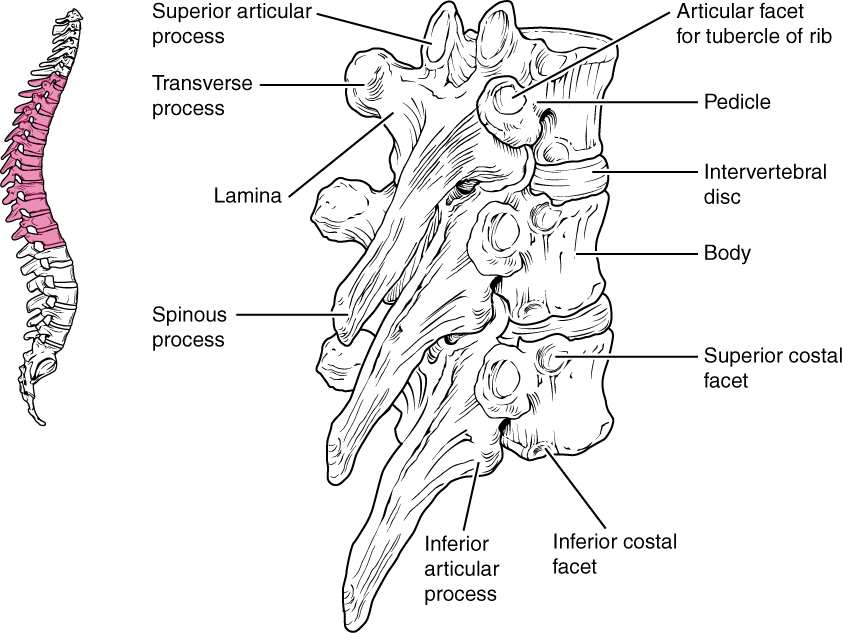

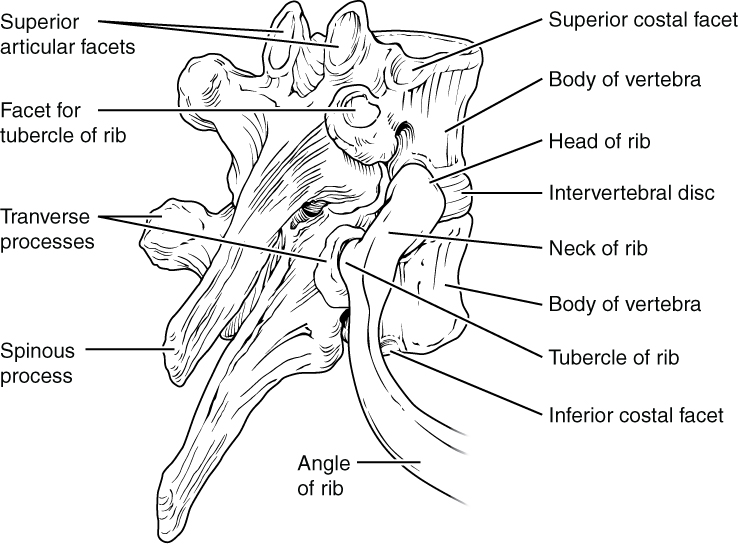

The bodies of the thoracic vertebrae are larger than those of cervical vertebrae (Figure 7.4.7).

Thoracic vertebrae have several additional articulation sites, each of which is called a facet, where a rib is attached. All thoracic vertebrae have facets located on the lateral sides of the body, each of which is called a costal facet (costal = “rib”). These are for articulation with the head (end) of a rib and are referred to as the superiorcostal facets and inferior costal facets. An additional facet is located on the transverse process for articulation with the tubercle of a rib.

Lumbar Vertebrae

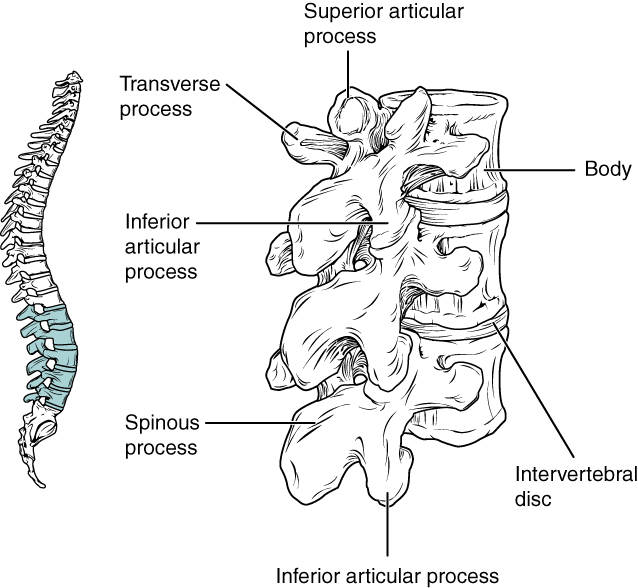

Lumbar vertebrae carry the greatest amount of body weight and are thus characterized by the large size and thickness of the vertebral body (Figure 7.4.9).

Sacrum and Coccyx

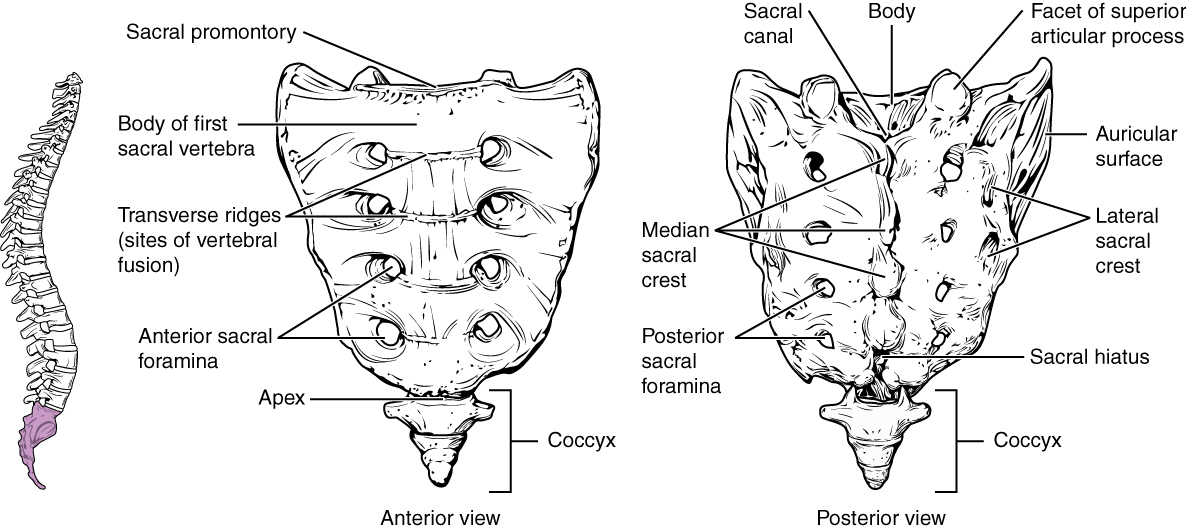

The sacrum is a triangular-shaped bone that is thick and wide across its superior base where it is weight bearing and then tapers down to an inferior, non-weight bearing apex (Figure 7.4.10). It is typically formed by the fusion of five sacral vertebrae, a process that does not begin until after the age of 20.

The coccyx, or tailbone, is derived from the fusion of four (or occassionally three or five) very small coccygeal vertebrae (see Figure 7.4.10). It is not weight bearing in the standing position, but may receive some body weight when sitting.

Intervertebral Discs and Ligaments of the Vertebral Column

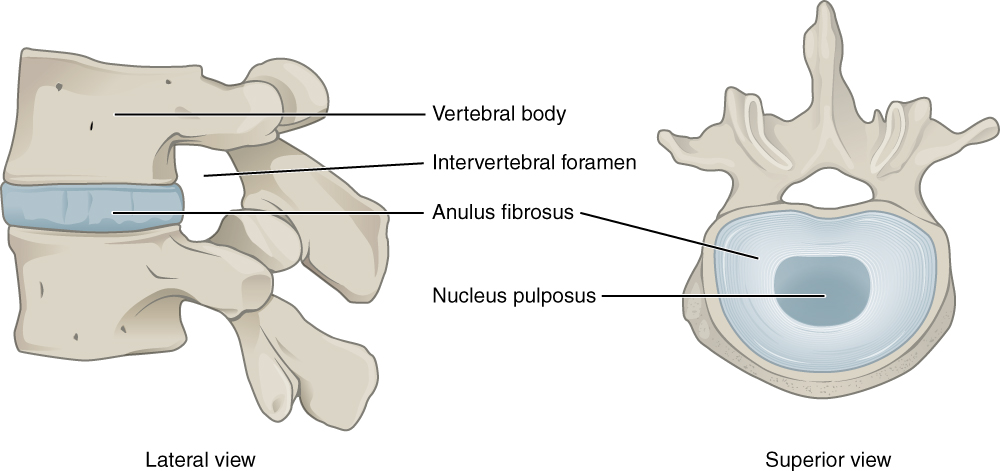

The bodies of adjacent vertebrae are strongly anchored to each other by an intervertebral disc. This structure provides padding between the bones during weight bearing, and because it can change shape, also allows for movement between the vertebrae. Although the total amount of movement available between any two adjacent vertebrae is small, when these movements are summed together along the entire length of the vertebral column, large body movements can be produced. Ligaments that extend along the length of the vertebral column also contribute to its overall support and stability.

Intervertebral Disc

An intervertebral disc is a fibrocartilaginous pad that fills the gap between vertebral bodies (see Figure 7.4.5). Each disc is anchored to the bodies of its adjacent vertebrae, thus strongly uniting them. The discs also provide padding between vertebrae during weight bearing. Because of this, intervertebral discs are thin in the cervical region and thickest in the lumbar region, which carries the most body weight. In total, the intervertebral discs account for approximately 25 percent of your length from the top of the pelvis and the base of the skull. Intervertebral discs are also flexible and can change shape to allow for movements of the vertebral column.

Each intervertebral disc consists of two parts, the tough, fibrous outer layer of the disc. and the inside comprises of softer, more gel-like material. It has a high water content that serves to resist compression and thus is important for weight bearing. With increasing age, the water content of the inside component gradually declines. This causes the disc to become thinner, decreasing total body height somewhat, and reduces the flexibility and range of motion of the disc, making bending more difficult.

Ligaments of the Vertebral Column

Adjacent vertebrae are united by ligaments that run the length of the vertebral column along both its posterior and anterior aspects (Figure 7.4.12). These serve to resist excess forward or backward bending movements of the vertebral column, respectively.

External Website

Use this tool to identify the bones, intervertebral discs, and ligaments of the vertebral column. The thickest portions of the anterior longitudinal ligament and the supraspinous ligament are found in which regions of the vertebral column?

Career Connections – Chiropractor

Chiropractors are health professionals who use nonsurgical techniques to help patients with musculoskeletal system problems that involve the bones, muscles, ligaments, tendons, or nervous system. They treat problems such as neck pain, back pain, joint pain, or headaches. Chiropractors focus on the patient’s overall health and can also provide counseling related to lifestyle issues, such as diet, exercise, or sleep problems. If needed, they will refer the patient to other medical specialists.

Chiropractors use a drug-free, hands-on approach for patient diagnosis and treatment. They will perform a physical exam, assess the patient’s posture and spine, and may perform additional diagnostic tests, including taking X-ray images. They primarily use manual techniques, such as spinal manipulation, to adjust the patient’s spine or other joints. They can recommend therapeutic or rehabilitative exercises, and some also include acupuncture, massage therapy, or ultrasound as part of the treatment program. In addition to those in general practice, some chiropractors specialize in sport injuries, neurology, orthopaedics, pediatrics, nutrition, internal disorders, or diagnostic imaging.

To become a chiropractor, students must have 3–4 years of undergraduate education, attend an accredited, four-year Doctor of Chiropractic (D.C.) degree program, and pass a licensure examination to be licensed for practice. With the aging of the baby-boom generation, employment for chiropractors is expected to increase.

Chapter Review

The vertebral column forms the neck and back. The vertebral column originally develops as 33 vertebrae, but is eventually reduced to 24 vertebrae, plus the sacrum and coccyx. The vertebrae are divided into the cervical region (C1–C7 vertebrae), the thoracic region (T1–T12 vertebrae), and the lumbar region (L1–L5 vertebrae). The sacrum arises from the fusion of five sacral vertebrae and the coccyx from the fusion of four small coccygeal vertebrae. The vertebral column has four curvatures, the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacrococcygeal curves. The thoracic and sacrococcygeal curves are primary curves retained from the original fetal curvature. The cervical and lumbar curves develop after birth and thus are secondary curves. The cervical curve develops as the infant begins to hold up the head, and the lumbar curve appears with standing and walking.

A typical vertebra consists of an enlarged anterior portion called the body, which provides weight-bearing support. Attached posteriorly to the body is a vertebral arch, which surrounds and defines the vertebral foramen for passage of the spinal cord.

The intervertebral discs fill in the gaps between the bodies of adjacent vertebrae. They provide strong attachments and padding between the vertebrae.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

1. Describe the vertebral column and define each region.

2. Describe the sacrum.

3. Describe the structure and function of an intervertebral disc.

Glossary

- anterior arch

- anterior portion of the ring-like C1 (atlas) vertebra

- anterior longitudinal ligament

- ligament that runs the length of the vertebral column, uniting the anterior aspects of the vertebral bodies

- anterior (ventral) sacral foramen

- one of the series of paired openings located on the anterior (ventral) side of the sacrum

- anulus fibrosus

- tough, fibrous outer portion of an intervertebral disc, which is strongly anchored to the bodies of the adjacent vertebrae

- atlas

- first cervical (C1) vertebra

- axis

- second cervical (C2) vertebra

- cervical curve

- posteriorly concave curvature of the cervical vertebral column region; a secondary curve of the vertebral column

- cervical vertebrae

- seven vertebrae numbered as C1–C7 that are located in the neck region of the vertebral column

- costal facet

- site on the lateral sides of a thoracic vertebra for articulation with the head of a rib

- dens

- bony projection (odontoid process) that extends upward from the body of the C2 (axis) vertebra

- facet

- small, flattened area on a bone for an articulation (joint) with another bone, or for muscle attachment

- inferior articular process

- bony process that extends downward from the vertebral arch of a vertebra that articulates with the superior articular process of the next lower vertebra

- intervertebral disc

- structure located between the bodies of adjacent vertebrae that strongly joins the vertebrae; provides padding, weight bearing ability, and enables vertebral column movements

- intervertebral foramen

- opening located between adjacent vertebrae for exit of a spinal nerve

- kyphosis

- (also, humpback or hunchback) excessive posterior curvature of the thoracic vertebral column region

- lamina

- portion of the vertebral arch on each vertebra that extends between the transverse and spinous process

- lateral sacral crest

- paired irregular ridges running down the lateral sides of the posterior sacrum that was formed by the fusion of the transverse processes from the five sacral vertebrae

- ligamentum flavum

- series of short ligaments that unite the lamina of adjacent vertebrae

- lordosis

- (also, swayback) excessive anterior curvature of the lumbar vertebral column region

- lumbar curve

- posteriorly concave curvature of the lumbar vertebral column region; a secondary curve of the vertebral column

- lumbar vertebrae

- five vertebrae numbered as L1–L5 that are located in lumbar region (lower back) of the vertebral column

- median sacral crest

- irregular ridge running down the midline of the posterior sacrum that was formed from the fusion of the spinous processes of the five sacral vertebrae

- nuchal ligament

- expanded portion of the supraspinous ligament within the posterior neck; interconnects the spinous processes of the cervical vertebrae and attaches to the base of the skull

- nucleus pulposus

- gel-like central region of an intervertebral disc; provides for padding, weight-bearing, and movement between adjacent vertebrae

- pedicle

- portion of the vertebral arch that extends from the vertebral body to the transverse process

- posterior arch

- posterior portion of the ring-like C1 (atlas) vertebra

- posterior longitudinal ligament

- ligament that runs the length of the vertebral column, uniting the posterior sides of the vertebral bodies

- posterior (dorsal) sacral foramen

- one of the series of paired openings located on the posterior (dorsal) side of the sacrum

- primary curve

- anteriorly concave curvatures of the thoracic and sacrococcygeal regions that are retained from the original fetal curvature of the vertebral column

- sacral canal

- bony tunnel that runs through the sacrum

- sacral foramina

- series of paired openings for nerve exit located on both the anterior (ventral) and posterior (dorsal) aspects of the sacrum

- sacral hiatus

- inferior opening and termination of the sacral canal

- sacral promontory

- anterior lip of the base (superior end) of the sacrum

- sacrococcygeal curve

- anteriorly concave curvature formed by the sacrum and coccyx; a primary curve of the vertebral column

- scoliosis

- abnormal lateral curvature of the vertebral column

- secondary curve

- posteriorly concave curvatures of the cervical and lumbar regions of the vertebral column that develop after the time of birth

- spinous process

- unpaired bony process that extends posteriorly from the vertebral arch of a vertebra

- superior articular process

- bony process that extends upward from the vertebral arch of a vertebra that articulates with the inferior articular process of the next higher vertebra

- superior articular process of the sacrum

- paired processes that extend upward from the sacrum to articulate (join) with the inferior articular processes from the L5 vertebra

- supraspinous ligament

- ligament that interconnects the spinous processes of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae

- thoracic curve

- anteriorly concave curvature of the thoracic vertebral column region; a primary curve of the vertebral column

- thoracic vertebrae

- twelve vertebrae numbered as T1–T12 that are located in the thoracic region (upper back) of the vertebral column

- transverse foramen

- opening found only in the transverse processes of cervical vertebrae

- transverse process

- paired bony processes that extends laterally from the vertebral arch of a vertebra

- vertebral arch

- bony arch formed by the posterior portion of each vertebra that surrounds and protects the spinal cord

- vertebral (spinal) canal

- bony passageway within the vertebral column for the spinal cord that is formed by the series of individual vertebral foramina

- vertebral foramen

- opening associated with each vertebra defined by the vertebral arch that provides passage for the spinal cord

Solutions

Answers for Critical Thinking Questions

- Answer: The adult vertebral column consists of 24 vertebrae, plus the sacrum and coccyx. The vertebrae are subdivided into cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions. There are seven cervical vertebrae (C1–C7), 12 thoracic vertebrae (T1–T12), and five lumbar vertebrae (L1–L5). The sacrum is derived from the fusion of five sacral vertebrae and the coccyx is formed by the fusion of four small coccygeal vertebrae.

- The sacrum is a single, triangular-shaped bone formed by the fusion of five sacral vertebrae. On the posterior sacrum, the median sacral crest is derived from the fused spinous processes, and the lateral sacral crest results from the fused transverse processes. The sacral canal contains the sacral spinal nerves, which exit via the anterior (ventral) and posterior (dorsal) sacral foramina. The sacral promontory is the anterior lip. The sacrum also forms the posterior portion of the pelvis.

- An intervertebral disc fills in the space between adjacent vertebrae, where it provides padding and weight-bearing ability, and allows for movements between the vertebrae. It consists of an outer anulus fibrosus and an inner nucleus pulposus. The anulus fibrosus strongly anchors the adjacent vertebrae to each other, and the high water content of the nucleus pulposus resists compression for weight bearing and can change shape to allow for vertebral column movements.

This work, Anatomy & Physiology, is adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, licensed under CC BY. This edition, with revised content and artwork, is licensed under CC BY-SA except where otherwise noted.

Images, from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, are licensed under CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Access the original for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction.