Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Discuss the process of bone formation and development.

- Explain the role of cartilage in bone formation

- List the steps of endochondral ossification

- Explain the growth activity at the epiphyseal plate

- Explain how bones remodel overtime

- Compare and contrast the processes of intramembranous and endochondral bone formation

- Compare and contrast the interstitial and appositional growth

In the early stages of embryonic development, the embryo’s skeleton consists of fibrous membranes and hyaline cartilage. By the sixth or seventh week of embryonic life, the actual process of bone development, ossification (osteogenesis), begins.

Intramembranous Ossification

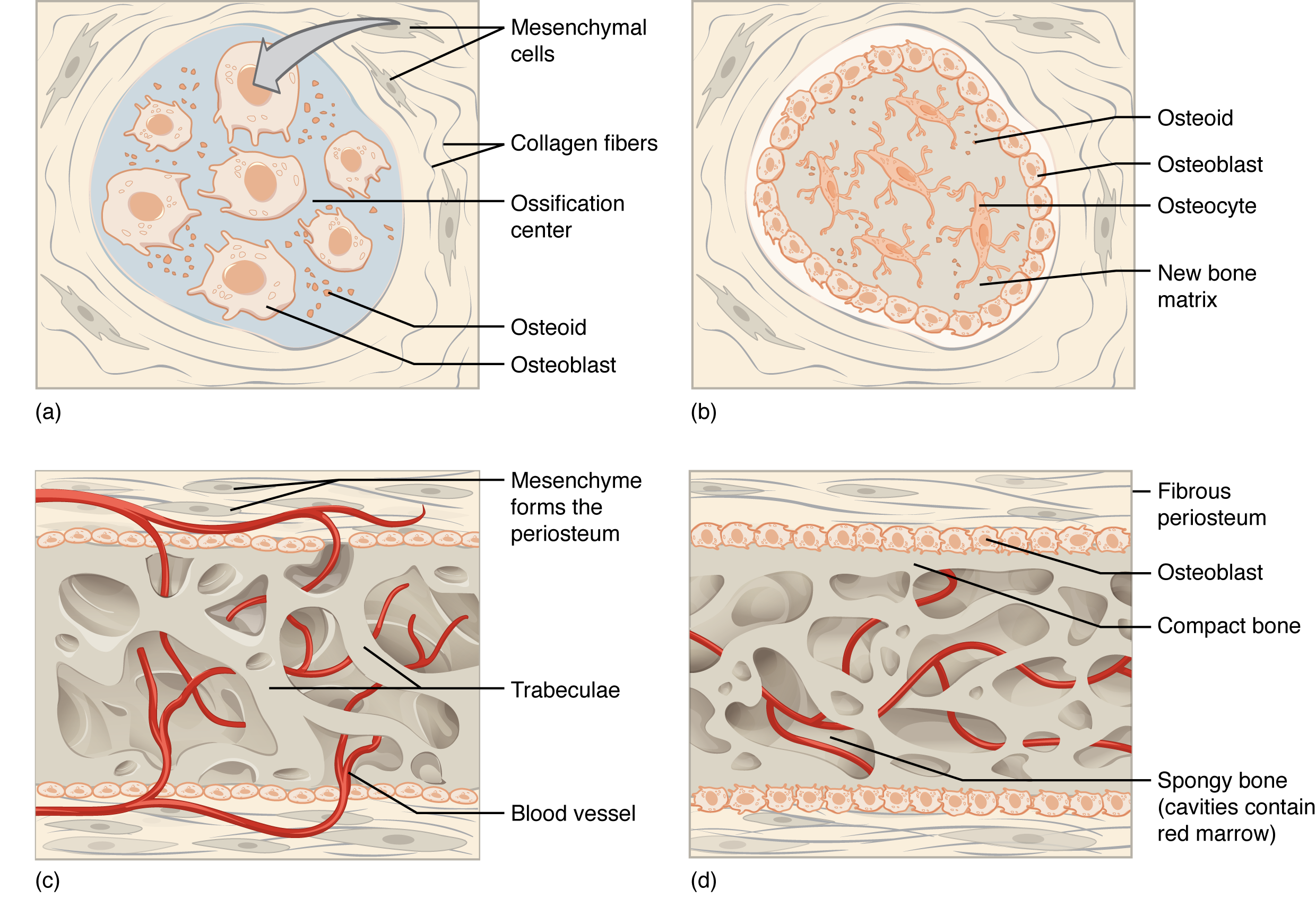

During intramembranous ossification, compact and spongy bone develops directly from sheets of connective tissue. The flat bones of the face, most of the cranial bones, and the clavicles (collarbones) are formed via intramembranous ossification.

Osteoblasts secrete osteoid, uncalcified matrix consisting of collagen precursors and other organic proteins, which calcifies (hardens) within a few days as mineral salts are deposited on it, thereby entrapping the osteoblasts within. Once entrapped, the osteoblasts become osteocytes (Figure 6.4.1b). As osteoblasts transform into osteocytes, osteogenic cells in the surrounding connective tissue differentiate into new osteoblasts at the edges of the growing bone.

Several clusters of osteoid unite around the capillaries to form a trabecular matrix, while osteoblasts on the surface of the newly formed spongy bone become the cellular layer of the periosteum (Figure 6.4.1c). The periosteum then secretes compact bone superficial to the spongy bone. The spongy bone crowds nearby blood vessels, which eventually condense into red bone marrow (Figure 6.4.1d). The new bone is constantly also remodeling under the action of osteoclasts (not shown).

Intramembranous ossification begins in utero during fetal development and continues on into adolescence. At birth, the skull and clavicles are not fully ossified nor are the junctions between the skull bone (sutures) closed. This allows the skull and shoulders to deform during passage through the birth canal. The last bones to ossify via intramembranous ossification are the flat bones of the face, which reach their adult size at the end of the adolescent growth spurt.

Endochondral Ossification

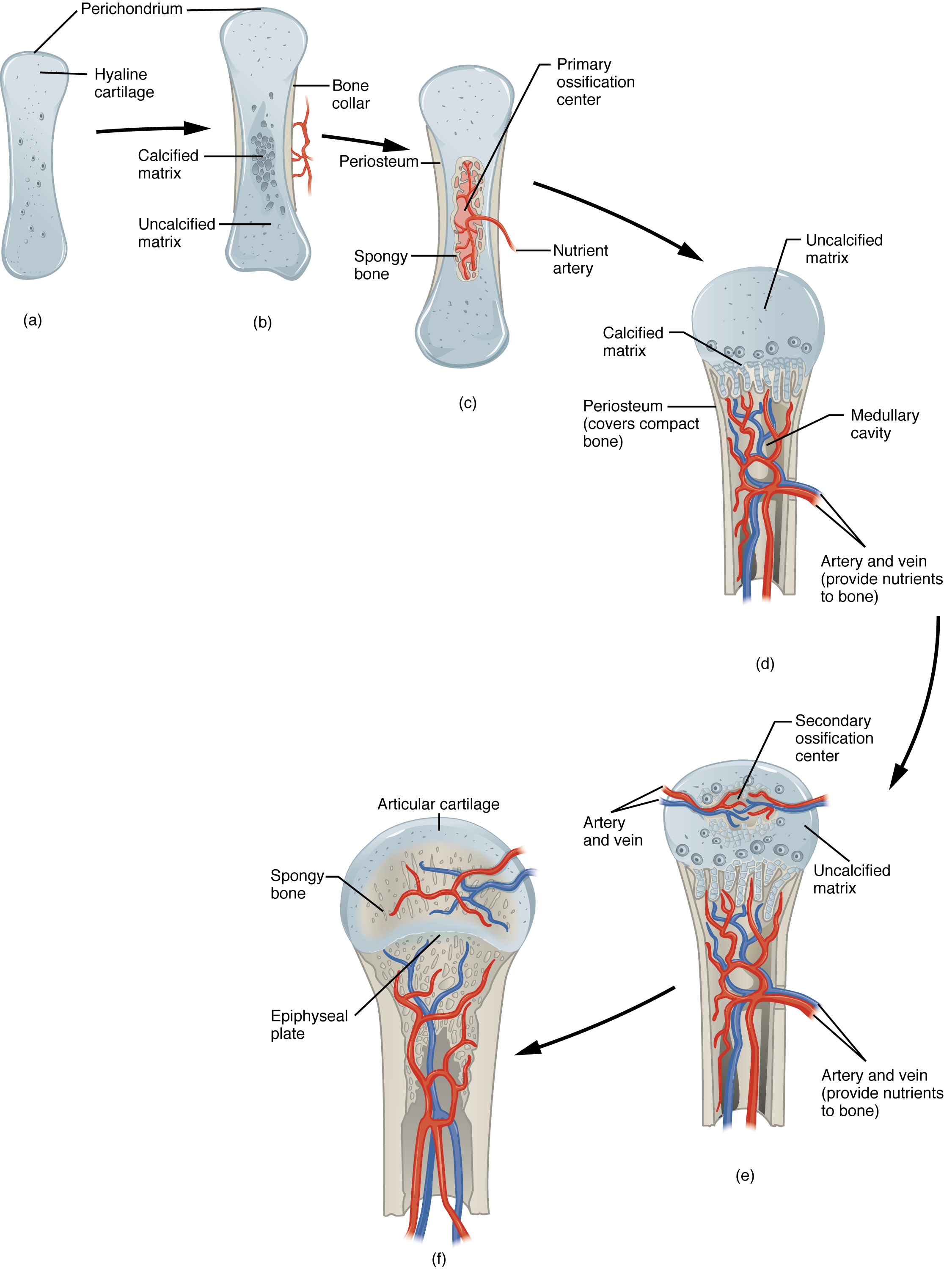

In endochondral ossification, bone develops by replacing hyaline cartilage. Cartilage does not become bone. Instead, cartilage serves as a template to be completely replaced by new bone. Endochondral ossification takes much longer than intramembranous ossification. Bones at the base of the skull and long bones form via endochondral ossification.

As more and more matrix is produced, the cartilaginous model grow in size. Blood vessels bring osteoblasts to the edges of the structure and these arriving osteoblasts deposit bone in a ring around the diaphysis – this is called a bone collar (Figure 6.4.2b). The bony edges of the developing structure prevent nutrients from diffusing into the center of the hyaline cartilage. This results in chondrocyte death and disintegration in the center of the structure. Without cartilage inhibiting blood vessel invasion, blood vessels penetrate the resulting spaces, not only enlarging the cavities but also carrying osteogenic cells with them, many of which will become osteoblasts. These enlarging spaces eventually combine to become the medullary cavity. Bone is now deposited within the structure creating the primary ossification center (Figure 6.4.2c).

While these deep changes are occurring, chondrocytes and cartilage continue to grow at the ends of the structure (the future epiphyses), which increases the structure’s length at the same time bone is replacing cartilage in the diaphyses. This continued growth is accompanied by remodeling inside the medullary cavity (osteoclasts were also brought with invading blood vessels) and overall lengthening of the structure (Figure 6.4.2d). By the time the fetal skeleton is fully formed, cartilage remains at the epiphyses and at the joint surface as articular cartilage.

After birth, this same sequence of events (matrix mineralization, death of chondrocytes, invasion of blood vessels from the periosteum, and seeding with osteogenic cells that become osteoblasts) occurs in the epiphyseal regions, and each of these centers of activity is referred to as a secondary ossification center (Figure 6.4.2e). Throughout childhood and adolescence, there remains a thin plate of hyaline cartilage between the diaphysis and epiphysis known as the growth or epiphyseal plate (Figure 6.4.2f). Eventually, this hyaline cartilage will be removed and replaced by bone to become the epiphyseal line.

How Bones Grow in Length

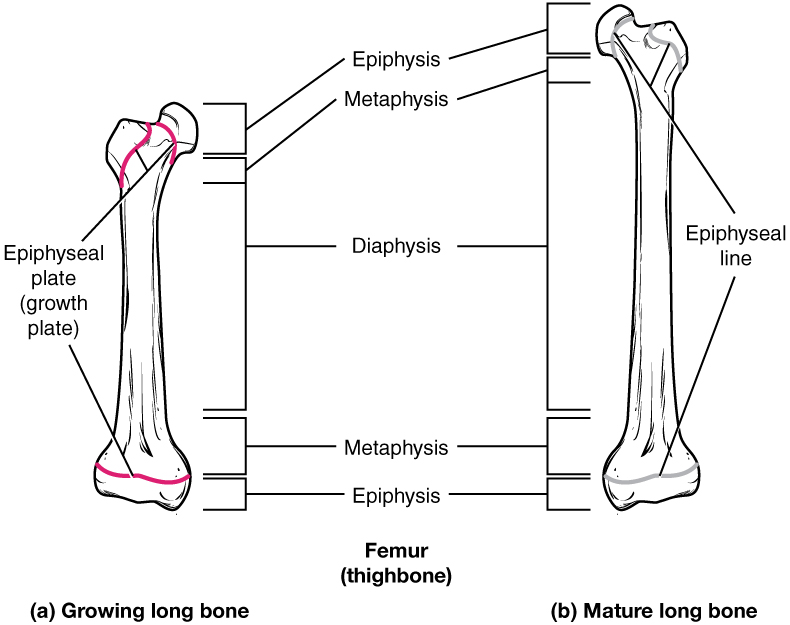

The epiphyseal plate is the area of elongation in a long bone. It includes a layer of hyaline cartilage where ossification can continue to occur in immature bones. As cartilage grows, the entire structure grows in length and then is turned into bone. Once cartilage cannot grow further, the structure cannot elongate more.

Bones continue to grow in length until early adulthood. The rate of growth is controlled by hormones, which will be discussed later. When the chondrocytes in the epiphyseal plate cease their proliferation and bone replaces all the cartilage, longitudinal growth stops. All that remains of the epiphyseal plate is the ossified epiphyseal line (Figure 6.4.4).

How Bones Grow in Diameter

While bones are increasing in length, they are also increasing in diameter; growth in diameter can continue even after longitudinal growth ceases. This growth can occur at the endosteum or peristeum where osteoclasts resorb old bone that lines the medullary cavity, while osteoblasts produce new bone tissue. The erosion of old bone along the medullary cavity and the deposition of new bone beneath the periosteum not only increase the diameter of the diaphysis but also increase the diameter of the medullary cavity. This remodeling of bone primarily takes place during a bone’s growth. However, in adult life, bone undergoes constant remodeling, in which resorption of old or damaged bone takes place on the same surface where osteoblasts lay new bone to replace that which is resorbed. Injury, exercise, and other activities lead to remodeling. Those influences are discussed later in the chapter, but even without injury or exercise, about 5 to 10 percent of the skeleton is remodeled annually just by destroying old bone and renewing it with fresh bone.

Diseases of the…Skeletal System Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a genetic disease in which bones do not form properly and therefore are fragile and break easily. It is also called brittle bone disease. The disease is present from birth and affects a person throughout life.

The genetic mutation that causes OI affects the body’s production of collagen, one of the critical components of bone matrix. The severity of the disease can range from mild to severe. Those with the most severe forms of the disease sustain many more fractures than those with a mild form. Frequent and multiple fractures typically lead to bone deformities and short stature. Bowing of the long bones and curvature of the spine are also common in people afflicted with OI. Curvature of the spine makes breathing difficult because the lungs are compressed.

Because collagen is such an important structural protein in many parts of the body, people with OI may also experience fragile skin, weak muscles, loose joints, easy bruising, frequent nosebleeds, brittle teeth, blue sclera, and hearing loss. There is no known cure for OI. Treatment focuses on helping the person retain as much independence as possible while minimizing fractures and maximizing mobility. Toward that end, safe exercises, like swimming, in which the body is less likely to experience collisions or compressive forces, are recommended. Braces to support legs, ankles, knees, and wrists are used as needed. Canes, walkers, or wheelchairs can also help compensate for weaknesses.

When bones do break, casts, splints, or wraps are used. In some cases, metal rods may be surgically implanted into the long bones of the arms and legs. Research is currently being conducted on using bisphosphonates to treat OI. Smoking and being overweight are especially risky in people with OI, since smoking is known to weaken bones, and extra body weight puts additional stress on the bones.

Section Review

All bone formation is a replacement process. During development, tissues are replaced by bone during the ossification process. In intramembranous ossification, bone develops directly from sheets of connective tissue. In endochondral ossification, bone develops by replacing hyaline cartilage. Activity in the epiphyseal plate enables bones to grow in length (this is interstitial growth). Appositional growth allows bones to grow in diameter. Remodeling occurs as bone is resorbed and replaced by new bone.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

In what ways do intramembranous and endochondral ossification differ?

Glossary

- appositional growth

- growth by adding to the free surface of bone, can occur at endosteum or periosteum

- endochondral ossification

- process in which bone forms by replacing hyaline cartilage

- epiphyseal line

- completely ossified remnant of the epiphyseal plate

- epiphyseal plate

- junction between epiphysis and diaphysis of growing long bone, contains hyaline cartilage being replaced by bone, site of long bone elongation

- interstitial growth

- growth by adding within the interior of a structure, occurs by hyaline cartilage at epiphyseal plate

- intramembranous ossification

- process by which bone forms directly from mesenchymal tissue

- ossification

- (also, osteogenesis) bone formation

- ossification center

- cluster of osteoblasts found in the early stages of intramembranous ossification

- osteoid

- uncalcified bone matrix secreted by osteoblasts, contains collagen and collagen pre-cursors

- perichondrium

- membrane that covers cartilage

- primary ossification center

- region, deep in the diaphysis, where bone development starts during endochondral ossification

- proliferative zone

- region of the epiphyseal plate that makes new chondrocytes to replace those that die at the diaphyseal end of the plate and contributes to longitudinal growth of the epiphyseal plate

- remodeling

- process by which osteoclasts resorb old or damaged bone at the same time as and on the same surface where osteoblasts form new bone to replace that which is resorbed

- reserve zone

- region of the epiphyseal plate that anchors the plate to the osseous tissue of the epiphysis

- secondary ossification center

- region of endochondral bone development in the epiphyses

- zone of calcified matrix

- region of the epiphyseal plate closest to the diaphyseal end; functions to connect the epiphyseal plate to the diaphysis

- zone of maturation and hypertrophy

- region of the epiphyseal plate where chondrocytes from the proliferative zone grow and mature and contribute to the longitudinal growth of the epiphyseal plate

Solutions

Answers for Critical Thinking Questions

- In intramembranous ossification, bone develops directly from sheets of mesenchymal connective tissue, but in endochondral ossification, bone develops by replacing hyaline cartilage. Intramembranous ossification is complete by the end of the adolescent growth spurt, while endochondral ossification lasts into young adulthood. The flat bones of the face, most of the cranial bones, and a good deal of the clavicles (collarbones) are formed via intramembranous ossification, while bones at the base of the skull and the long bones form via endochondral ossification.

- A single primary ossification center is present, during endochondral ossification, deep in diaphysis. Like the primary ossification center, secondary ossification centers are present during endochondral ossification, but they form later, and there are at least two of them, one in each epiphysis.

- Interstitial growth occurs in hyaline cartilage of epiphyseal plate, increases length of growing bone. Appositional growth occurs at endosteal and periosteal surfaces, increases width of growing bones. Interstitial growth only occurs as long as hyaline is present, cannot occur after epiphyseal plate closes. Appositional growth can continue throughout life.

This work, Anatomy & Physiology, is adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, licensed under CC BY. This edition, with revised content and artwork, is licensed under CC BY-SA except where otherwise noted.

Images, from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, are licensed under CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Access the original for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction.