5

Section one: The fundamentals

A)

Exercise 1: Notebook Prompt

Many of you are likely familiar with the concept of “ability inequity,” which the authors of this article define as “an unjust or unfair (a) ‘distribution of access to and protection from abilities generated through human interventions’ or (b) ‘judgment of abilities intrinsic to biological structures such as the human body’.”

However, they go on to identify the following “ability concepts” that are less familiar:

1) ability security (one is able to live a decent life with whatever set of abilities one has)

2) ability identity security (to be able to be at ease with ones abilities)

How prevalent are these forms of security among disabled people you know? Or, if you identify as a disabled person, would you say your social surroundings and community foster and support these kinds of security? Furthermore, while the focus of the article is on Kinesiology programs, it is also important to reflect on how academia in general accommodates for disability. If you feel comfortable answering this question, what has been your experience of postsecondary education to date?

-OR-

The authors also observe that “Ableism not only intersects with other forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, ageism, and classism, but abilities are often used to justify such negative ‘isms’.”

What do you think this means? Provide an example.

| in the reading, authors Arora and Wolbring observe that ableism intersects with other forms of oppression like racism, sexism, ageism, and classism, but more importantly that abilities are often used to justify these negative “isms”. This means that perceived “abilities” or “lack there of” are typically weaponized to support and validate other forms of discrimination. They pair together to reinforce one another and acquire strength. Essentially, these oppressive systems use the idea that certain groups are less capable, whether it be physically, intellectually, or emotionally, to justify their marginalization and discrimination. For example, racism has historically been justified through ableism by portraying racialized groups as “less intelligent” or “weaker”. These ideas reinforce the false notion that they are inherently inferior to another group but also promote ableist thought by defining capabilities and highlighting abnormality and perceived failure as a personal and moral failure. During colonialism we see this as well, in our history and present, Idnigenous peoples are labeled as unfit and uncivilized, implying a lack of ability to govern themsleves. So, in every sense, colonialism inspired ableism to breed. This is a disgusting way that society rationalizes forced assimilation, ableism, and racism. Very similarly, sexism has been justified through ableist beliefs by portraying women as too emotional and too weak to take on leadership roles or decide big things for themsleves. This reinforces patriarchal, colonial control by framing the supposed lack of ability as a reason to exclude specific groups from holding power. In each case, ableism works alongside every other form of oppression by using perceived failures or deficits in ability as a way to legitimize and justify inequality. In doing so, this maintains systemic control and oppressive structures.

|

Exercise 2: Implicit Bias Test

Did anything surprise you about the results of the test? Please share if you’re comfortable OR comment on the usefulness of these kinds of tests more generally.

| To be very honest, I found this test to be super confusing and rather unaccessible for being a test to determine ableism. I do however think these types of tests, tests that inspire thought and discussion but that accurately measure, can be extremely beneficial for education, introspective deconstruction, and overall self growth when conducted correctly and preferably in an entirely different manner. When I first did the test, the results were inconclusive since I got so many “wrong”. I was so confused. The second go, it suggested I have a moderate automatic preference for Physically able people over physically disabled people. I think it was an overall confusing task that I feel does not accurately measure morals, beliefs, feelings, anything really besides the physical ability to press the screen fast and register when you are seeing which is again, somewhat ableist in it of itself. I most definitely know I am bias towards myself, but if I am being honest I do not believe I have any preference to physically abled people. I have several physically disabled friends and like to think of myself as an ally to the. I also have taken several disability studies courses throughout my time at Trent and am currently in one now titled Feminism and Disability, these classes have heightened my awareness of inherent biases and ableism, educating my on ways to combat it and promote equality for every body, no matter the ability. However, I feel it is extremely important to continue educating myself and to always be open to feedback on ways I can improve in being a better friend to disabled folk.

|

B) Keywords

Exercise 3:

Add the keyword you contributed to padlet and briefly (50 words max) explain its importance to you.

|

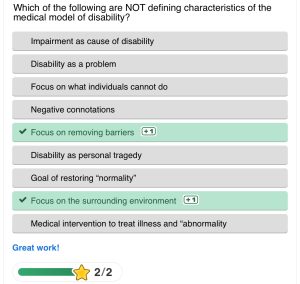

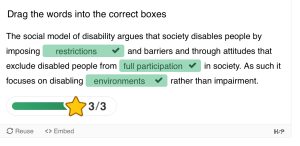

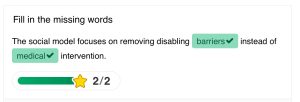

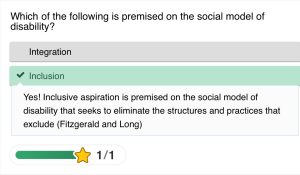

The social model of disability is opposite to the medical model of disability as it prioritizes a vastly different approach to understanding the implications of ableism and the production of it. The social model of disability view disability as a product of societal barriers, not as individual impairments or differences. People are disabled because of the way in which society is organized and laid out through physical obstacles, systemic barriers, and attitudinal biases that develop through the other two societal features, rather than by their medical conditions or physical limitations. This model shifts the focus form “fixing” the individual to restructuring and fixing society by removing these physical and emotional barriers and work toward developing an inclusive environment. This model empowers the individual and fights for systemic change in accessibility and attitude.This concept is very important to me as it reflects a lot of important concepts I have learned throughout my time in the sociology department at Trent University. I also am currently taking a Feminism and Disability class where I had to create an art piece as a form of activism and referenced De’VIA art (a form of Deaf artistry that emphasizes sign language). The social model aligns with my work in this class and the assignment because it emphasized systemic change and representation, and I highlighted in my piece the Trump administrations policies that affect marginalized communities. My art does not just demonstrate individual struggles, it critiques the societal structure that created those struggle

|

B) On Disability

Exercise 4: Complete the Activities

Exercise 5: Notebook Prompt

What do Fitzgerald and Long identify as barriers to inclusion and how might these apply to sport in particular?

Fitzgerald and Long identify several barriers to inclusion within their text and directly reference the inclusion for disabled folk several times, including institutional and structural challenges, marginalization in integrated settings, and the stigmatization that occurs through segregation. One key aspect of their text that stood out to me was the emphasis on how integration of disabled folk into the mainstream sport world can sometimes lead to marginalization rather than inclusion. For example, integration, where disabled people are included in a space typically dominated by non-disabled people, can result in the disabled person feeling alienation or overshadowed, even belittled in some cases by the dominant group. Fitzgerald and Long emphasize that simply placing disabled people into mainstream sport settings does not necessarily promote inclusion and it is not the bandaid fix that they assume, as the focus on performance or competition can lead to feelings of inadequacy or exclusion if the disabled participants are unable to compete on equal terms . Additionally though, the authors note that the lack of inclusive pedagogy prevents meaningful engagement. The authors advocate for a flexible and multi-modal approach that doesn’t slap a bandaid on a bullet hole, but rather combines integration, reverse integration, and separate provisions when needed to ensure equal opportunities for disabled people who participate in sport. I did enjoy their discussion on reverse intergration, however, I can see faults in this method as it can still lead to feelings of inadequacy and also take up space in spots where they actually feel comfortable.

C) Inclusion, Integration, Separation

Exercise 6: Complete the Activities

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

Choose ONE of the three questions Fitzgerald and Long argue disability sport needs to address and record your thoughts in your Notebook.

- Should sport be grouped by ability or disability?

- Is sport for participation or competition?

- Should sport competitions be integrated?

| 1. Should sport be grouped by ability or disability

This is a tricky question, I think whether sport should be grouped by ability or disability strongly depends on the individual and their specific needs, because everyone no matter the ability is so different and has specific requirements to fulfill their desires. As I work for BGC, where we cater to children with a variety of abilities, I have seen that sometimes an inclusive approach where multiple ability levels can succeed and have fun. For example, one time at a day camp, a boy in a wheelchair chair was playing soccer, we gave him a mini-stick and a leader ran around pushing him to help him move around the gym and play soccer. We explained to the rest of the group that the priority was equity in the situation and we described what equity meant; giving people the tools they need to succeed the same way another person would. The boy playing soccer not only absolutely loved it, but told us after that he did not think he could ever play soccer because of his limitations. I went home that day not only proud of what we had accomplished, but excited for more adaptations in the sports we play. However, I feel as though I can not speak for disabled folk, as I am not physically disabled myself. Therefore, I believe it all comes down to the approach and what works best for the person involved.

|

Part Two: Making Connections

A) Gender, Sport and Disability

Exercise 8: Complete the Activity

The paradox that sportswomen habitually face (as the authors observe, this isn’t confined to disabled sportswomen) involves the expectation they will be successful in a ‘masculine’ environment while complying with femininity norms in order to be recognized as a woman.

True or false? : TRUE !

Take a moment to reflect on this paradox below (optional).

| This nuanced dynamic that women in sports face, having to succeed in “masculine” sports while still conforming to feminine norms, highlights a conflicting and unfair expectation placed upon women. They must be strong, competitive, and physically dominant, yet also graceful, attractive, and non-threatening. This double standard is so frustrating as it not only reinforces the idea that femininity is at odds with athletic achievement, but moreover, it dismisses femininity as weak while promoting toxic hegemonic masculinity as the standard for competitiveness and strength. When thinking on this paradox, Ilona Maher, an American rugby player is a prime example of an athlete who challenges this paradox. Maher actively embraces and showcases her femininity, particularly through social media, while not fitting the conventional definition of “beautiful”. For example, on TikTok recently, Maher posted a video of her in a gorgeous dress with the caption, “ the feminine urge to pick outfits that show my muscles” (Posted on 3/20). Maher is muscular and tall, both of which are not within the normal boundary of femininity. However, Maher just compete in the past season of Dancing With The Stars and demonstrated her beauty, strength, and grace all in one. She wore sparkly dresses, heels, and makeup while lifting her male partner and completing intense tricks flawlessly. In doing so, she demonstrated that femininity and strength go hand and hand. Additionally, in doing this she pushes back against the toxic masculinity that dominates traditionally male sports. The expectation that athletes must embody toughness , aggression, and emotional restraint leads to the devaluation of traits associated with femininity, such as empathy, collaboration, and self expression. These expectations pose that the art AND sport of dance is not an actual athletic activity. This creates a culture where women in sports must over preform in both areas to be taken seriously while men in sports feel pressured to reject anything perceived as “soft” in order to maintain dominance. Women like Maher and her success in both rugby and danced fight against these outdated and misogynistic standards by proving athleticism is not confined to one rigid definition. If anything, her ability to move between two vastly different physical disciplines underscores the reality that strength takes many forms. |

B) Masculinity, Disability, and Murderball

Exercise 9: Notebook/Padlet Prompt

Watch the film, Murderball and respond to the question in the padlet below (you will have an opportunity to return to the film at the end of this module).

The authors of “Cripping Sport and Physical Activity: An Intersectional Approach to Gender and Disability” observe that the “gendered performance of the wheelchair rugby players can…be interpreted as a form of resistance to marginalized masculinity” (332) but also point out that it may reinforce “ableist norms of masculinity.” After viewing the film, which argument do you agree with?

a) Murderball celebrates a kind of resistance to marginalized masculinity

| I chose answer D) because Murderball both challenges and reinforces traditional ideals of masculinity and creates a complex portrayal of both gender and disability. The film resists marginalized masculinity by showing quadriplegic athletes who dismiss the stereotype that disability equates to weakness. Through their aggression, competitiveness, and skill in wheelchair rugby, these athletes within the documentary assert their dominance and strength as well as highlight their autonomy by proving disability does not diminish their manhood. Their ability to engage in a high-contact, physically demanding sport challenges the notion that athleticism and masculinity is exclusive to able-bodied individuals, redefining what strength and ability can look like. However, two things can be true at the same time and while the film does celebrate a resistance to marginalized masculinity, it also reinforces ableist and hegemonic norms of masculinity in emphasizing aggression and physical dominance as central to male identity. The athletes often embody hyper-masculine traits and distance themselves from softer narratives of disability. The athletes rejection of being seen as weak symbols of perserverance does align with main stream ideals of masculinity that prioritizes strength over vulnerability and emotional health. This duality, challenging stereotypes while reinforcing gender expactions, is why I believe the film does both. |

Section Three: Taking a Shot

A) Resistance

B) Calling out Supercrip

Exercise 10: Mini Assignment (worth 5% in addition to the module grade)

1) Do you agree with the critique of the “supercrip” narrative in this video? Why or why not? Find an example of the “supercrip” Paralympian in the 2024 Paris Paralympics or Special Olympics coverage and explain how it works.

| The “supercrip” narrative portrayals athletes with disabilities as extraordinary for merely participating or “overcoming” their impairments while dismissing and/or overshadowing their athletic achievements. I agree with the critique of the “supercrip” narrative in the video for this exact reason. This narrative reduces the complexity of the disabled experience to a simple story of triumph used for inspiration porn and therefore it not only overlooks the real challenges that disabled folk face in day-to-day life but also positions them as exceptional or extraordinary not for their actual skills or talents, but for their ability to “overcome” disability. This framing is patronizing, belittling, and limiting. Additionally, perpetuates a harmful divide between paralympians and non-disabled athletes by focusing more on their disability rather than their athleticism. This reminds me of the film Murderball where one athlete compared their sport to the special olympics and ( although poorly worded) stated they weren’t “retards” and found it frustrating when people think they are just there for a participation medal. The critique of “supercrip” within the video from the article Grappling with Ableism in the Para-Sport Movement points out that such narratives fail to represent the true, diverse, and very nuanced experiences of disabled athletes. This failure to accurately represent disabled athletes goes beyond just the Paralympics and influences how society perceives disability in general. When the media, like the video from this module, continuously frame disabled individuals as inspirational simply for existing or participating, it reinforces the idea that disability is something to be pitied and overcome rather than it being a different way of moving through the world. This not only devalues the efforts of paralympians but also puts unrealistic expectations on disabled folk who may not aspire to elite athleticism in the same way that I do not either as an abled bodied person. To me, an example of the “supercrip” narrative in action can be seen in the way social media and the public discuss Hunter Woodhall, a Paralympic sprinter, in comparison to his wife, Tara Davis-Woodhall, an Olympic long jumper. Despite Hunter being a decorated athlete with multiple Paralympic medals, Woodhall is often framed in media and social commentary as “inspiring” simply for competing with prosthetic legs rather than being recognized for his speed and athletic ability. Meanwhile, his relationship with Tara is used to reinforce ableist stereotypes in the media, with comments implying that he is “lucky” to have her. These remarks reduce Hunter to an object of inspiration and pity rather than a world-class athlete just like his wife. Ultimately, the “supercrip” narrative does a disservice to disabled athletes who are incredibly skillful and far more athletic than there “supercrip” commenters. “Supercrip” ideology creates an artificial separation between disabled and non-disabled athletes, focusing on disability as the defining characteristic rather than their training, dedication, and skill. |

2) Does the film Murderball play into the supercrip narrative in your opinion? How does gender inform supercrip (read this blog for some ideas)?

(300 words for each response)

| This is a tricky and nuanced question for me. While I think the film does engage with some aspects of the “supercrip” narrative, I find it more so resists and complicated it in key ways. As discussed, the “supercrip” trope typically frames disabled individuals as extraordinary and inspirational for “overcoming” their impairments, highlighting their perseverance in ways that reinforce ableist ideas. In doing so, it devalues the real experiences and tribulations disabled people face admist their “resiliency” and diminishes their being to that of “inspiration porn”. Murderball does highlight the athletes toughness and resilience, however, the film resists the traditional inspirational framing of disability by rejectin pity and refusing to position the athletes as exceptional to the rule. Instead of focusing on overcoming disability, the documentary presents wheelchair rugby as a legitimate and intense sport, rather than a spectacle of inspiration. I find that the athletes themselves do an excellent job as dismantling this “supercrip” narrative. I also think that gender plays a crucial component in shaping the narratve in the film. Traditional masculine ideals value strength, dominance, and intensity, qualities that align with the trope when applied to disabled athletes. The men in Murderball actively reject any association with fragility and weakness which aligns with the hyper-masculine aspects of the “supercrip” narrative. Rather than being seen as victims who need to be admired for simply existing, they assert their masculinity through physical dominance. However, this framing still engages with the “supercrip” narrative, as it suggests that to be valued and respected, disabled men must embody the same ideals of toughness that define able-bodied masculinity. In this way, I think the film both resists and reinforces the “supercrip” stereotype by on one hand rejecting the pity and passive inspiration association with disability and on the other promoting a version of disability that can only be celebrated when it aligns with traditional masculinity and physical dominance. This identifies a deeper issue within the trop: it forces disabled individuals into narrow categories, where they must either be objects of inspiration or proof they can compete on able-bodied terms. |