12. Competition and Cooperation in Our Social Worlds

Chapter Learning Objectives

1. Conflict, Cooperation, Morality, and Fairness

- Review the situational variables that increase or decrease competition and conflict.

- Differentiate harm-based morality from social conventional morality, and explain how morality works to help people cooperate.

- Define distributive justice and procedural justice, and explain the influence of fairness norms on cooperation and competition.

2. How the Social Situation Creates Conflict: The Role of Social Dilemmas

- Explain the concepts of public goods and social dilemmas, and how these conflicts influence human interactions.

- Describe the principles of the prisoner’s dilemma game that make it an effective model for studying social dilemmas.

- Review the different laboratory games that have been used to study social dilemmas.

- Summarize the individual difference and cultural variables that relate to cooperation and competition.

3. Strategies for Producing Cooperation

- Outline the variables that increase and decrease competition.

- Summarize the principles of negotiation, mediation, and arbitration.

The Collapse of Atlantic Canada’s Cod Fishery

“Why are you abusing me, I didn’t take the fish out of the goddamned water.” These famous words were uttered by John Crosbie, the federal minister of fisheries and oceans in Canada on July 1, 1992, when he met with a group of fishers who were upset about the alarming decline in the cod population. A day later (under police protection), Crosbie announced that a moratorium would be imposed on fishing North Atlantic cod, an action that effectively put 40,000 people out of work overnight. More than 20 years later there is little sign of growth in the cod population and the moratorium is still in place.

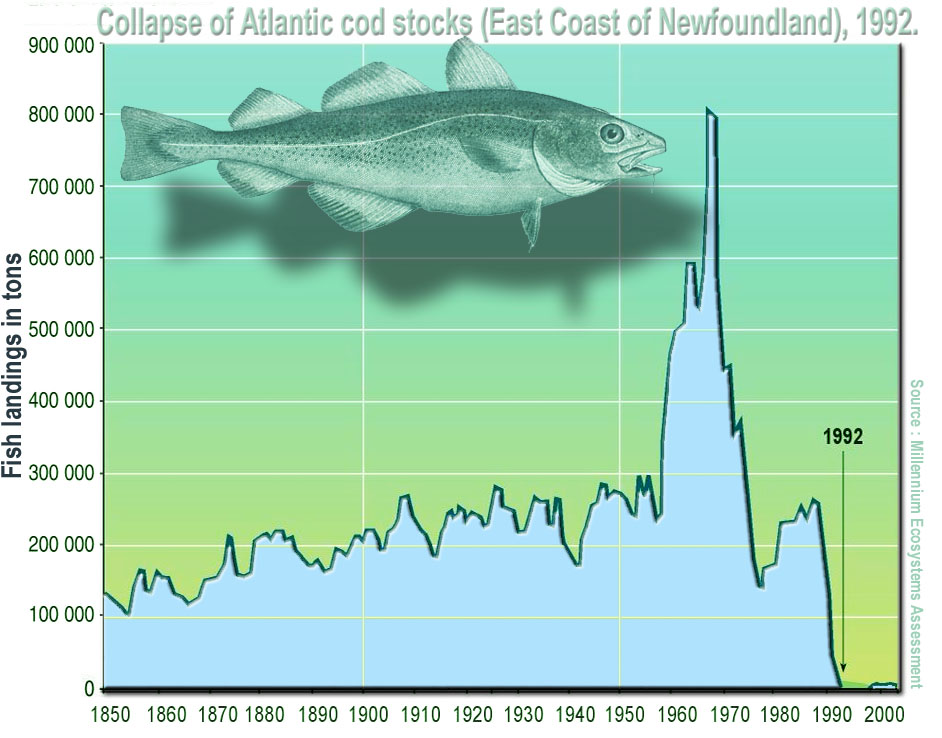

For generations of Atlantic fishers who had grown used to an ocean full of fish, this was an unfathomable outcome. Yet it was this very reputation of an ocean teeming with cod that had attracted giant fishing trawlers from distant countries to the waters off the coast of Newfoundland since the 1950s. As the fish stocks dwindled, the trawlers began to use sonar, satellite navigation, and new techniques to dredge the ocean floor to collect entire schools of cod. As you can see in Figure 12.1, the annual cod catch fell dramatically, from a high of 800,000 tons in 1968 to less than 200,000 tons a decade later.

Even as awareness of the problem grew in the 1980s, Canadian politicians were too afraid of the short-term impact of job losses in the fishing industry to reduce the quota of cod that fishers were permitted to catch. Eventually, however, this short-term thinking lead to long-term catastrophe, as Atlantic Canada’s once-thriving fishing industry collapsed, a victim of overfishing and a case study in poor fisheries management.

Sources: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/remembering-the-mighty-cod-fishery-20-years-after-moratorium-1.1214172

One of the most important themes of this book has been the extent to which the two human motives of self-concern and other-concern guide our everyday behavior. We have seen that although these two underlying goals are in many ways in direct opposition to each other, they nevertheless work together to create successful human outcomes. Particularly important is the fact that we cannot protect and enhance ourselves and those we care about without the help of the people around us. We cannot live alone—we must cooperate, work with, trust, and even provide help to other people in order to survive. The self-concern motive frequently leads us to desire to not do these things because they sometimes come at a cost to the self. And yet in the end, we must create an appropriate balance between self and other.

In this chapter, we revisit this basic topic one more time by considering the roles of self-concern and other-concern in social relationships between people and the social groups they belong to, and among social groups themselves. We will see, perhaps to a greater extent than ever before, how important our relationships with others are and how careful we must be to develop and use these connections. Most important, we will see again that helping others also helps us help ourselves.

Furthermore, in this chapter, we will investigate the broadest level of analysis that we have so far considered—focusing on the cultural and societal level of analysis. In so doing, we will consider how the goals of self-concern and other-concern apply even to large groups of individuals, such as nations, societies, and cultures, and influence how these large groups interact with each other.

Most generally, we can say that when individuals or groups interact they may take either cooperative or competitive positions (De Dreu, 2010; Komorita & Parks, 1994). When we cooperate, the parties involved act in ways that they perceive will benefit both themselves and others. Cooperation is behavior that occurs when we trust the people or groups with whom we are interacting and are willing to communicate and share with the others, expecting to profit ourselves through the increased benefits that can be provided through joint behavior. On the other hand, when we engage in competition we attempt to gain as many of the limited rewards as possible for ourselves, and at the same time we may work to reduce the likelihood of success for the other parties. Although competition is not always harmful, in some cases one or more of the parties may feel that their self-interest has not been adequately met and may attribute the cause of this outcome to another party (Miller, 2001). In these cases of perceived inequity or unfairness, competition may lead to conflict, in which the parties involved engage in violence and hostility (De Dreu, 2010).

Although competition is normal and will always be a part of human existence, cooperation and sharing are too. Although they may generally look out for their own interests, individuals do realize that there are both costs and benefits to always making selfish choices (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978). Although we might prefer to use as much gasoline as we want, or to buy a new music album rather than contribute to the local food bank, at the same time we realize that doing so may have negative consequences for the group as a whole. People have simultaneous goals of cooperating and competing, and the individual must coordinate these goals in making a choice (De Dreu, 2010; Schelling, 1960/1980).

We will also see that human beings, as members of cultures and societies, internalize social norms that promote other-concern, in the form of morality and social fairness norms, and that these norms guide the conduct that allows groups to effectively function and survive (Haidt & Kesebir, 2010). As human beings, we want to do the right thing, and this includes accepting, cooperating, and working with others. And we will do so when we can. However, as in so many other cases, we will also see that the social situation frequently creates a powerful force that makes it difficult to cooperate and easy to compete.

A social dilemma is a situation in which the goals of the individual conflict with the goals of the group (Penner, Dovidio, Piliavin, & Schroeder, 2005; Suleiman, Budescu, Fischer, & Messick, 2004; Van Lange, De Cremer, Van Dijk, & Van Vugt, 2007). Social dilemmas impact a variety of important social problems because the dilemma creates a type of trap: even though an individual or group may want to be cooperative, the situation leads to competitive behavior. For instance, the fishers we considered in the chapter opener found themselves in a social dilemma—they wanted to continue to catch as many cod as they could, and yet if they all did so, the supply would continue to fall, making the situation worse for everyone.

Although social dilemmas create the potential for conflict and even hostility, those outcomes are not inevitable. People usually think that situations of potential conflict are fixed-sum outcomes, meaning that a gain for one side necessarily means a loss for the other side or sides (Halevy, Chou, & Murnighan, 2011). But this is not always true. In some cases, the outcomes are instead integrative outcomes, meaning that a solution can be found that benefits all the parties. In the last section of this chapter, we will consider the ways that we can work to increase cooperation and to reduce competition, discussing some of the contributions that social psychologists have made to help solve some important social dilemmas (Oskamp, 2000a, 2000b).

References

De Dreu, C. K. W. (2010). Social conflict: The emergence and consequences of struggle and negotiation. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 983–1023). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Haidt, J., & Kesebir, S. (2010). Morality. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 797–832). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Halevy, N., Chou, E. Y., & Murnighan, J. K. (2011). Mind games: The mental representation of conflict. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2011-20586-001&site=ehost-live

Kelley, H. H., & Thibaut, J. W. (1978). Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Komorita, S. S., & Parks, C. D. (1994). Social dilemmas. Dubuque, IA: Brown & Benchmark

Miller, D. T. (2001). Disrespect and the experience of injustice. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 527–553.

Oskamp, S. (2000a). Psychological contributions to achieving an ecologically sustainable future for humanity. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 373–390.

Oskamp, S. (2000b). A sustainable future for humanity? How can psychology help? American Psychologist, 55(5), 496–508.

Penner, L. A., Dovidio, J. F., Piliavin, J. A., & Schroeder, D. A. (2005). Prosocial behavior: Multilevel perspectives. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 365–392.

Schelling, T. (1960/1980). The strategy of conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Suleiman, R., Budescu, D. V., Fischer, I., & Messick, D. M. (Eds.). (2004). Contemporary psychological research on social dilemmas. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Van Lange, P. A. M., De Cremer, D., Van Dijk, E., & Van Vugt, M. (Eds.). (2007). Self-interest and beyond: Basic principles of social interaction. New York, NY: Guilford Press.