Ernest Hemmingway, Nobel-winning author, was once asked what the scariest thing he had ever encountered was: he replied simply “a blank piece of paper” (as cited by MIT Global Studies and Languages).

The first step in getting started on a writing project often seems daunting. Staring at a blank computer screen waiting for inspiration to come and write the paper for you though is rarely the right approach.

Don’t stare at the screen! Instead, try prewriting!

Many students — and some teachers — skip the pre-writing stage of the writing process because they see it as unnecessarily time-consuming. However, the truth is that Pre-Writing can actually save you time, especially when you take the time to do it well.

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to

– how 5 minutes of pre-writing can save you hours later on

Why is Prewriting Beneficial?

Prewriting is an essential part of the entire writing process because this is when you start to get your ideas on paper.

The term “pre-writing” is used to describe any activity used at the beginning of the writing process to generate ideas and think about how those ideas connect to the larger writing project.

Basically, Prewriting is thinking on paper.

For example, written notes and outlines, including graphic organizers, can serve as a record of one’s ideas and the sources of those ideas. A preliminary thesis or hypothesis could inform the process and the product.

Prewriting has many benefits including

- Reduces Anxiety and Stress by breaking the writing process into smaller parts

- Increases Quality by giving writers a chance to recognize weaker ideas

- Allows writers to organize their ideas

- Helps you to recognize how much you already know about the topic

- Allows you to generate many ideas quickly without judgement

Many people do brainstorm without recording those ideas and sources in permanent form prior to the next steps in the writing process. Most developing writers, however, need to record their pre-writing ideas in permanent form so that those ideas can clearly inform and guide the thinking and writing process, resulting in a coherent, well-organized product or text.

Remember, the goal of Prewriting is to capture your ideas early so that you have an anchor to refer back to later. Taking as little as five minutes at the start of the writing process helps you establish a starting point that will keep your on track throughout the project.

Prewriting in NOT a burdensome extra step; it’s an essential first step.

Prewriting Strategies

The term “pre-writing” conjures up a lot of strange activities and practices. You’ve probably tried many different prewriting strategies in the past, and may have a good idea of what works for you and what doesn’t.

Keep in mind that the KIND of writing project you’re working on can impact how effective a particular technique is to use in a given situation. Something that you’ve relied on before may not be as effective as you move into new subjects. Experiment often.

Make it fun! Here are some to try:

Strategy 1: Freewriting

Free writing is a popular prewriting strategy, but not everyone recognizes it as prewriting.

When Freewriting, you write as much as you can for a short period of time about everything you currently know about the topic. Even ideas that may seem to be off topic or unrelated get written down.

How does Freewriting Work?

1. Write the topic/question at the top of the page

2. Set a timer for a short amount of time (5 minutes or 10 minutes are good options).

2. Write anything and everything that comes to mind related to your topic/question. If you think it, you need to write it. If it’s hard for you to “turn off” the worry about writing well, challenge yourself to write a few awful, terrible sentences as the beginning. It’s also a good trick to write as if you were writing a letter to a friend and trying to decide what you know about a topic.

-

-

-

- Don’t worry about spelling or grammar

- Don’t stop to think about only the good ideas

- Don’t erase anything

- Don’t force yourself to write in your second language

- Don’t take your pen/pencil off the page

-

-

3. Review and highlight key ideas in what you wrote. Look for any phrases or words that look interesting to you. Circle them (or if you are typing, highlight, italicize, bold, or underline them).

4. Set the timer again, but this time focus on the most interesting word or phrase from your first freewrite. Sometimes even a third round can help you narrow the topic further.

Remember, Freewriting is all about idea generation and exploration.

Strategy 2: List-Making

If you’re a list-maker by nature, there’s no reason not to harness that for academic writing purposes.

Listing is just what it sounds like: making a list of ideas related to the topic that you are exploring or the question that you need to answer.

How does List-Making Work?

-

- Write the Topic/Question at the top of the page

- List all the ideas you can think of related to your topic.

- Do write each idea on a separate line

- Do write down any idea no matter how outrageous or off topic

- Don’t censor your ideas or worry about whether it’s a good idea or not

- Don’t stop to organize or group ideas

- Do add doodles, images or icons to help you get your ideas on paper

- Do use whatever language that makes you comfortable (including texting)

- Do think of synonyms for the question words if you get stuck for ideas

- Review and Highlight key ideas/phrases that you find in your list. You may even want to build a second list based on one of your ideas or a list of what you don’t know about a topic to help guide your research.

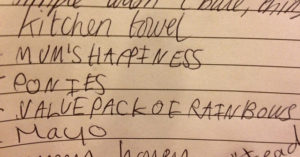

Here’s an example of a list that includes images, phrases, keywords and questions

Strategy 3: Clustering

Unlike Freewriting and List-Making, Clustering is a method of prewriting that asks you to consider how ideas connect together as you generate ideas draw rather than waiting till afterwards. This technique has many names: a tree diagram, a map, a spider diagram, and brainstorm are among the most common.

Clustering can be a great approach for anyone who likes to think spatially and focus on how ideas can be connected to one another. In fact, one way to define clustering is to to see it as “an open minded, non-linear visual structuring of ideas, in which a student free-associates strings of ideas around a central word or idea” (Rico, 1983; as cited by Owen, 2019).

How Does Clustering Work?

-

- Write the topic/question in the centre of a blank page.

- Write any ideas related to the centre topic/question around the perimeter of your question.

- Draw connecting lines (branches) to link each idea back to the centre.

- Add related branches connected to each of your ideas. To help you expand the branches, ask yourself questions like

- For example?

- So what?

- Why is this idea important?

- How is this idea/example/quote relevant to the centre topic/question?

Mapping is a great visual means of gathering your ideas. Here are a few different methods to get started:

-

- Use concept-mapping software such as Inspiration or SmartDraw.

- Use concept-mapping websites such as MindMeister (http://www.mindmeister.com/).

- Create your own circles and lines within a word processing program.

- Draw your map by hand.

Example: Clustering

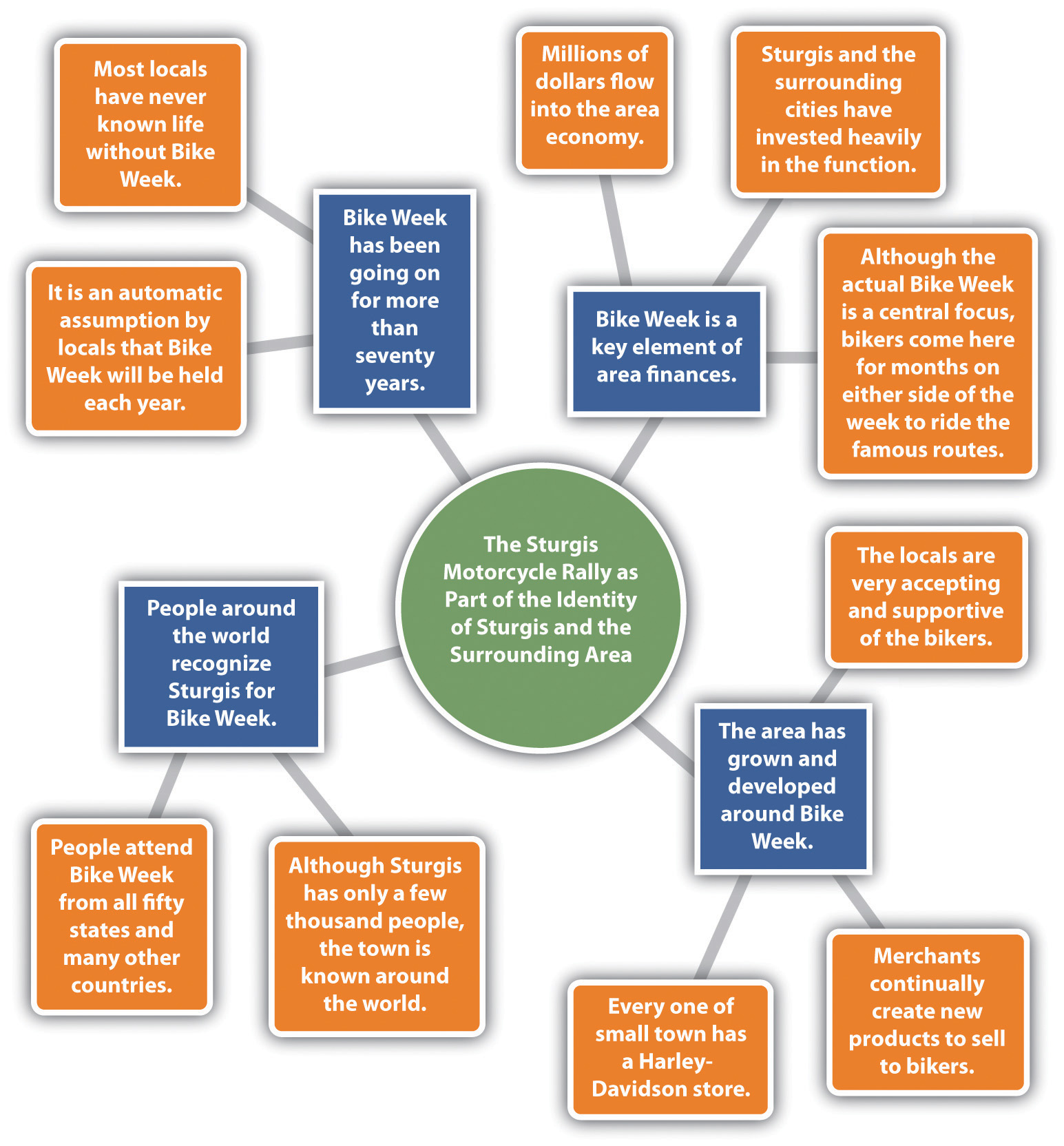

The example below, “Concept Map of Sturgis Motorcycle Rally” , is an example of how clustering can work using an online word processor.

This map was made in Microsoft Word by creating circles, squares, and lines and placing them by hand into position. You can use all circles or all squares or whatever shape(s) you would like. This map uses a combination of squares and circles to make the subtopics stand out clearly from the details. This map also uses color to differentiate between levels.

Strategy 4: Questioning

When you’re faced with a writing project on a topic that you have limited knowledge of, asking questions is often the most straight forward and efficient way to get started.

When you have a topic in mind, asking and answering questions about it is a good way to figure out directions your writing might take.

How does Questioning Work?

- Write the question/topic at the top of the page.

- Write a list of question that you need/want to learn about regarding your topic. If you need some inspiration, focus on the typical journalist questions (sometimes called the five W’s) which is an effective way to write about the basic information about your topic.

- Who: Who is involved? Who is affected?

- What: What is happening? What will happen? What should happen?

- Where: Where is it happening?

- When: When is it happening?

- Why/how: Why is this happening? How is it happening?

- Write a second list of questions that directly reflect the assignment that you are working on

- Problem/Solution: What is the problem that your writing is trying to solve? Who or what is part of the problem? What solutions can you think of? How would each solution be accomplished?

- Cause/Effect: What is the reason behind your topic? Why is it an issue? Conversely, what is the effect of your topic? Who will be affected by it?

Bringing it all together: The Working Thesis Statement

The final piece of the prewriting puzzle is developing the working thesis.

Students often see a thesis statement as an object of mystery.

But it’s really not that mysterious. In fact, it helps to realize that thesis statements are friend, not foe. They are often quite useful tools, both in helping you write and in making sure the final product is powerful.

What is a Working Thesis?

Simply put, a working thesis is a one sentence statement that tells the reader

(1) your topic

(2) your position/opinion on that topic

(3) your 3+ key arguments/ideas to support your opinion

Your working thesis also directly answers the assigned question for an essay assignment.

When you’ve decided on a topic and explored it with prewriting activities, drafting a working thesis is a very helpful next step. Using the information in your prewriting, you can create the first version of your thesis statement.

As you complete the next stages of the writing process, you may find that your working thesis needs to change to reflect new ideas or research. That’s okay. In fact, that’s exactly why writing is considered a process.

References

This chapter includes information taken from:

Burnell, C., Wood, J., Babin, M., Pesznecker, S., & Rosevear, N. (2017). The word on college reading and writing. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/wordcollegerw/. CC BY-NC 4.0.

Lumen Learning. (n.d.). Prewriting. In Basic reading and writing. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-basicreadingwriting/chapter/outcome-prewriting/. CC BY.

Owen, J. (2019). The importance of prewriting in EFL academic writing classes. In EFL Magazine. https://eflmagazine.com/the-importance-of-prewriting-in-efl-academic-writing-classes/

Saylor Academy. (2012). Freewriting and mapping. In Handbook for writers. https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_handbook-for-writers/s09-02-freewriting-and-mapping.html. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Media Attributions

Blue anchor image is used under the ClipartKey licence

Concept map of Sturgis Motorcycle Rally from Handbook for writers by Saylor Academy is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Friend or foe? by Janet 59 is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Image of a black coloured pencil by William Warby is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Image of a question mark by Deans_Icon is under the Pixaby licence

Image of a handwritten list by Lucy Downey is licensed under CC BY

Image of a mind map by Jason Morrison is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

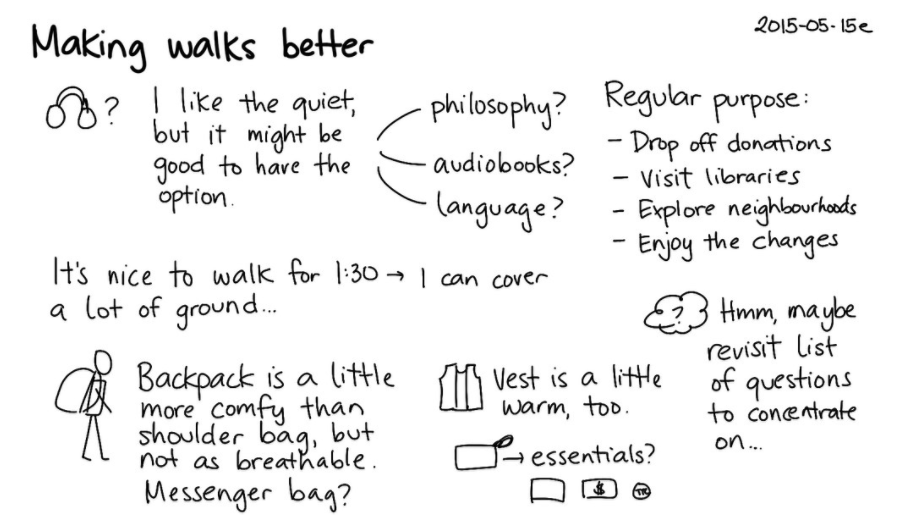

“Making Walks Better” by Sacha Chua is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Public domain image of Albert Einstein with his quote “Imagination is more important than knowledge” is available through The Nobel Prize’s Twitter account

Public domain image of Ernest Hemingway in Kenya is available through Wikimedia