3.2 Evaluating sources

Learning Objectives

- Critically evaluate the sources of the information you have found

- Apply the information from each source to your research proposal

- Identify how to be a responsible consumer of research

In Chapter 2, you developed a “working question” to guide your inquiry and learned how to use online databases to find sources. By now, you’ve hopefully collected a number of academic journal articles relevant to your topic area. It’s now time to evaluate the information you found. Not only do you want to be sure of the source and the quality of the information, but you also want to determine whether each item is an appropriate fit for your literature review.

This is also the point at which you make sure you have searched for and obtained publications for all areas of your research question and that you go back into the literature for another search, if necessary. You may also want to consult with your professor or the syllabus for your class to see what is expected for your literature review. In my class, I have specific questions I will ask students to address in their literature reviews.

It is likely that most of the resources you locate for your review will be from the scholarly literature of your discipline or in your topic area. As we have already seen, peer-reviewed articles are written by and for experts in a field. They generally describe formal research studies or experiments with the purpose of providing insight on a topic. You may have located these articles through the four databases in Chapter 2 or through archival searching. You now may want to know how to evaluate the usefulness for your research.

In general, when we discuss evaluation of sources, we are talking about quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation, currency, and credibility factors in a specific work, whether it’s a book, ebook, article, website, or blog posting. Before you include a source in your literature review, you should clearly understand what it is and why you are including it. According to Bennard et al. (2014), “Using inaccurate, irrelevant, or poorly researched sources can affect the quality of your own work” (para. 4). When evaluating a work for inclusion in, or exclusion from, your literature review, ask yourself a series of questions about each source.

-

- Is the information outdated? Is the source more than 5-10 years old? If so, it will not provide what we currently know about the topic–just what we used to know. Older sources are helpful for historical information, but unless historical analysis is the focus of your literature review, try to limit your sources to those that are current.

- How old are the sources used by the author? If you are reading an article from 10 years ago, they are likely citing material from 15-20 years ago. Again, this does not reflect what we currently know about a topic.

- Does the author have the credentials to write on the topic? Search the author’s name in a general web search engine like Google. What are the researcher’s academic credentials? What else has this author written? Search by author in the databases and see how much they have published on any given subject.

- Who published the source? Books published under popular press imprints (such as Random House or Macmillan) will not present scholarly research in the same way as Sage, Oxford, Harvard, or the University of Washington Press. For grey literature and websites, check the About Us page to learn more about potential biases and funding of the organization who wrote the report.

- Is the source relevant to your topic? How does the article fit into the scope of the literature on this topic? Does the information support your thesis or help you answer your question, or is it a challenge to make some kind of connection? Does the information present an opposite point of view, so you can show that you have addressed all sides of the argument in your paper? Many times, literature searches will include articles that ultimately are not that relevant to your final topic. You don’t need to read everything!

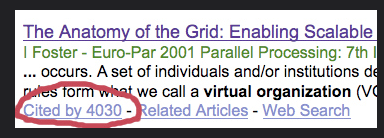

- How important is this source in the literature? If you search for the article on Google Scholar (see Figure 3.1 for an example of a search result from Google Scholar), you can see how many other sources cited this information. Generally, the higher the number of citations, the more important the article. This is a way to find seminal articles – “A classic work of research literature that is more than 5 years old and is marked by its uniqueness and contribution to professional knowledge” (Houser, 2018, p. 112).

Figure 3.1 Google Scholar - Is the source accurate? Check the facts in the article. Can statistics be verified through other sources? Does this information seem to fit with what you have read in other sources?

- Is the source reliable and objective? Is a particular point of view or bias immediately obvious, or does it seem objective at first glance? What point of view does the author represent? Are they clear about their point of view? Is the article an editorial that is trying to argue a position? Is the article in a publication with a particular editorial position?

- What is the scope of the article? Is it a general work that provides an overview of the topic or is it specifically focused on only one aspect of your topic?

- How strong is the evidence in the article? What are the research methods used in the article? Where does the method fall in the hierarchy of evidence?

- Meta-analysis and meta-synthesis: a systematic and scientific review that uses quantitative or qualitative methods (respectively) to summarize the results of many studies on a topic.

- Experiments and quasi-experiments: include a group of patients in an experimental group, as well as a control group. These groups are monitored for the variables/outcomes of interest. Randomized control trials are the gold standard.

- Longitudinal surveys: follow a group of people to identify how variables of interest change over time.

- Cross-sectional surveys: observe individuals at one point in time and discover relationships between variables.

- Qualitative studies: use in-depth interviews and analysis of texts to uncover the meaning of social phenomen

The last point above comes with some pretty strong caveats, as no study is really better than another. Foremost, your research question should guide which kinds of studies you collect for your literature review. If you are conducting a qualitative study, you should include some qualitative studies in your literature review so you can understand how others have studied the topic before you. Even if you are conducting a quantitative study, qualitative research is important for understanding processes and the lived experience of people. Any article that demonstrates rigor in thought and methods is appropriate to use in your inquiry.

At the beginning of a project, you may not know what kind of research project you will ultimately propose. It is at this point that consulting a meta-analysis, meta-synthesis, or systematic review might be especially helpful as these articles try to summarize an entire body of literature into one article. Every type of source listed here is reputable, but some have greater explanatory power than others.

Thinking about your project

Thinking about the overarching goals of your research project and finding and reviewing the existing literature on your topic are two of the initial steps you’ll take when designing a research project. Forming a working research question, as discussed in section 2.1, is another crucial step. Creating and refining your research question will help you identify the key concepts you will study. Once you have identified those concepts, you’ll need to decide how to define them, and how you’ll know that you’re observing them when it comes time to collect your data. Defining your concepts, and knowing them when you see them, relates to conceptualization and operationalization. Of course, you also need to know what approach you will take to collect your data. Thus, identifying your research method is another important part of research design.

You also need to think about who your research participants will be and what larger group(s) they may represent. Last, but certainly not least, you should consider any potential ethical concerns that could arise during the course of your research project. These concerns might come up during your data collection, but they might also arise when you get to the point of analyzing or sharing your research results.

Decisions about the various research components do not necessarily occur in sequential order. In fact, you may have to think about potential ethical concerns even before zeroing in on a specific research question. Similarly, the goal of being able to make generalizations about your population of interest could shape the decisions you make about your method of data collection. Putting it all together, the following list shows some of the major components you’ll need to consider as you design your research project. Make sure you have information that will help inform how you think about each component.

- Research question

- Literature review

- Research strategy (idiographic or nomothetic, inductive or deductive)

- Units of analysis and units of observation

- Key concepts (conceptualization and operationalization)

- Method of data collection

- Research participants (sample and population)

- Ethical concerns

Being a responsible consumer of research

Being a responsible consumer of research requires you to take seriously your identity as a social scientist. Now that you are familiar with how to conduct research and how to read the results of others’ research, you have some responsibility to put your knowledge and skills to use. Doing so is in part a matter of being able to distinguish what you do know based on the information provided by research findings from what you do not know. It is also a matter of having some awareness about what you can and cannot reasonably know as you encounter research findings.

When assessing social scientific findings, think about what information has been provided to you. In a scholarly journal article, you will presumably be given a great deal of information about the researcher’s method of data collection, her sample, and information about how the researcher identified and recruited research participants. All of these details provide important contextual information that can help you assess the researcher’s claims. If, on the other hand, you come across some discussion of social scientific research in a popular magazine or newspaper, chances are that you will not find the same level of detailed information that you would find in a scholarly journal article. In this case, what you do and do not know is more limited than in the case of a scholarly journal article. If the research appears in popular media, search for the author or study title in an academic database.

Also, take into account whatever information is provided about a study’s funding source. Most funders want, and in fact require, that recipients acknowledge them in publications. But more popular press may leave out a funding source. In this Internet age, it can be relatively easy to obtain information about how a study was funded. If this information is not provided in the source from which you learned about a study, it might behoove you to do a quick search on the web to see if you can learn more about a researcher’s funding. Findings that seem to support a particular political agenda, for example, might have more or less weight once you know whether and by whom a study was funded.

There is some information that even the most responsible consumer of research cannot know. Because researchers are ethically bound to protect the identities of their subjects, for example, we will never know exactly who participated in a given study. Researchers may also choose not to reveal any personal stakes they hold in the research they conduct. While researchers may “start where they are,” we cannot know for certain whether or how researchers are personally connected to their work unless they choose to share such details. Neither of these “unknowables” is necessarily problematic, but having some awareness of what you may never know about a study does provide important contextual information from which to assess what one can “take away” from a given report of findings.

Key Takeaways

- Not all published articles are the same. Evaluating sources requires a careful investigation of each source.

- Being a responsible consumer of research means giving serious thought to and understanding what you do know, what you don’t know, what you can know, and what you can’t know.

Image attributions

130329-A-XX000-001 by Master Sgt. Michael Chann public domain

- Figure 3.1 “The anatomy of the grid” was created by Palreeparit, I. (2008). Shared under a CC BY-NC 2.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/). Retrieved from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/isriya/2189574180/in/photolist-a9Aag6-dkHnih-a9AaeP-8Zp6Uj-aPaf9T-dnWd4t-akvThj-aGy9Un-bkTacm-3GRVMW-nQvuoX-6tZCiK-s6vUhN-fmnN9M-6S5See-tokn5N-nETnGy-nEUyTv-4ku97Y ↵