2.3 Finding literature

Learning Objectives

- Describe useful strategies to employ when searching for literature

- Identify how to narrow down search results to the most relevant sources

One of the drawbacks (or joys, depending on your perspective) of being a researcher in the 21st century is that we can do much of our work without ever leaving the comfort of our recliners. This is certainly true of familiarizing yourself with the literature. Most libraries offer incredible online search options and access to important databases of academic journal articles.

A literature search usually follows these steps:

- Building search queries

- Finding the right database

- Skimming the abstracts of articles

- Looking at authors and journal names

- Examining references

- Searching for meta-analyses and systematic reviews

Step 1: Building a search query with keywords

What do you type when you are searching for something on Google? Are you a question-asker? Do you type in full sentences or just a few keywords? What you type into a database or search engine like Google is called a query. Well-constructed queries get you to the information you need faster, while unclear queries will force you to sift through dozens of irrelevant articles before you find the ones you want.

The words you use in your search query will determine the results you get. Unfortunately, different studies often use different words to mean the same thing. A study may describe its topic as substance abuse, rather than addiction. Think of different keywords that are relevant to your topic area and write them down. Often in social work research, there is a bit of jargon to learn in crafting your search queries. If you wanted to learn more about people of low-income who do not have access to a bank account, you may need to learn the jargon term “unbanked,” which refers to people without bank accounts, and include “unbanked” in your search query. If you wanted to learn about children who take on parental roles in families, you may need to include “parentification” as part of your search query. As undergraduate researchers, you are not expected to know these terms ahead of time. Instead, start with the keywords you already know. Once you read more about your topic, start including new keywords that will return the most relevant search results for you.

Google is a “natural language” search engine, which means it tries to use its knowledge of how people to talk to better understand your query. Google’s academic database, Google Scholar, incorporates that same approach. However, other databases that are important for social work research—such as Academic Search Complete, PSYCinfo, and PubMed—will not return useful results if you ask a question or type a sentence or phrase as your search query. Instead, these databases are best used by typing in keywords. Instead of typing “the effects of cocaine addiction on the quality of parenting,” you might type in “cocaine AND parenting” or “addiction AND child development.” Note: you would not actually use the quotation marks in your search query for these examples.

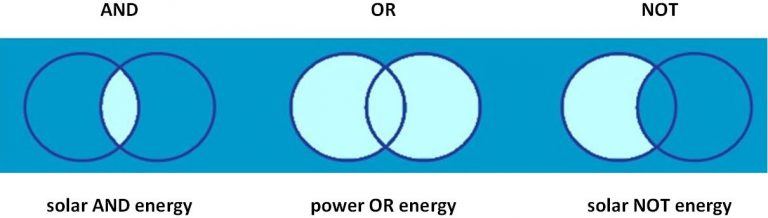

These operators (AND, OR, NOT) are part of what is called Boolean searching. Boolean searching works like a simple computer program. Your search query is made up of words connected by operators. Searching for “cocaine AND parenting” returns articles that mention both cocaine and parenting. There are lots of articles on cocaine and lots of articles on parenting, but fewer articles on both of those topics. In this way, the AND operator reduces the number of results you will get from your search query because both terms must be present. The NOT operator also reduces the number of results you get from your query. For example, perhaps you wanted to exclude issues related to pregnancy. Searching for “cocaine AND parenting NOT pregnancy” would exclude articles that mentioned pregnancy from your results. Conversely, the OR operator would increase the number of results you get from your query. For example, searching for “cocaine OR parenting” would return not only articles that mentioned both words but also those that mentioned only one of your two search terms. This relationship is visualized in Figure 2.1 below.

As my students have said in the past, probably the most frustrating part about literature searching is looking at the number of search results for your query. How could anyone be expected to look at hundreds of thousands of articles on a topic? Don’t worry. You don’t have to read all those articles to know enough about your topic area to produce a good research study. A good search query should bring you to at least a few relevant articles to your topic, which is more than enough to get you started. However, an excellent search query can narrow down your results to a much smaller number of articles, all of which are specifically focused on your topic area. Here are some tips for reducing the number of articles in your topic area:

- Use quotation marks to indicate exact phrases, like “mental health” or “substance abuse.”

- Search for your keywords in the ABSTRACT. A lot of your results may be from articles about irrelevant topics simply that mention your search term once. If your topic isn’t in the abstract, chances are the article isn’t relevant. You can be even more restrictive and search for your keywords in the TITLE. Academic databases provide these options in their advanced search tools.

- Use multiple keywords in the same query. Simply adding “addiction” onto a search for “substance abuse” will narrow down your results considerably.

- Use a SUBJECT heading like “substance abuse” to get results from authors who have tagged their articles as addressing the topic of substance abuse. Subject headings are likely to not have all the articles on a topic but are a good place to start.

- Narrow down the years of your search. Unless you are gathering historical information about a topic, you are unlikely to find articles older than 10-15 years to be useful. They no longer tell you the current knowledge on a topic. All databases have options to narrow your results down by year.

- Talk to a librarian. They are professional knowledge-gatherers, and there is often a librarian assigned to your department. Their job is to help you find what you need to know.

Step 2: Finding the right database

The big four databases you will probably use for finding academic journal articles relevant to social work are: Google Scholar, Academic Search Complete, PSYCinfo, and PubMed. Each has distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Because Google Scholar is a natural language search engine, you are more likely to get what you want without having to fuss with wording. It can be linked via Library Links to your university login, allowing you to access journal articles with one click on the Google Scholar page. Google Scholar also allows you to save articles in folders and provides a (somewhat correct) APA citation for each article. However, Google Scholar also will automatically display not only journal articles, but books, government and foundation reports, and gray literature. You need to make sure that the source you are using is reputable. Look for the advanced search feature to narrow down your results further.

Academic Search Complete is available through your school’s library, usually under page titled databases. It is similar to Google Scholar in its breadth, as it contains a number of smaller databases from a variety of social science disciplines (including Social Work Abstracts). You have to use Boolean searching techniques, and there are a number of advanced search features to further narrow down your results.

PSYCinfo and PubMed focus on specific disciplines. PSYCinfo indexes articles on psychology, and PubMed indexes articles related to medical science. Because these databases are more narrowly targeted, you are more likely to get the specific psychological or medical knowledge you desire. If you were to use a more general search engine like Google Scholar, you may get more irrelevant results. Finally, it is worth mentioning that many university libraries have a meta-search engine which searches all the databases to which they have access.

Step 3: Skimming abstracts and downloading articles

Once you’ve settled on your search query and database, you should start to see articles that might be relevant to your topic. Rather than read every article, skim through the abstract and see if that article is really one you need to read. If you like the article, make sure to download the full text PDF to your computer so you can read it later. Part of the tuition and fees your university charges you goes to paying major publishers of academic journals for the privilege of accessing their articles. Because access fees are incredibly costly, your school likely does not pay for access to all the journals in the world. While you are in school, you should never have to pay for access to an academic journal article. Instead, if your school does not subscribe to a journal you need to read, try using inter-library loan to get the article. On your university library’s homepage, there is likely a link to inter-library loan. Just enter the information for your article (e.g. author, publication year, title), and a librarian will work with librarians at other schools to get you the PDF of the article that you need. After you leave school, getting a PDF of an article becomes more challenging. However, you can always ask an author for a copy of their article. They will usually be happy to hear someone is interested in reading and using their work.

What do you do with all of those PDFs? I usually keep mine in folders on my cloud storage drive, arranged by topic. For those who are more ambitious, you may want to use a reference manager like Mendeley or RefWorks, which can help keep your sources and notes organized. At the very least, take notes on each article and think about how it might be of use in your study.

Step 4: Searching for author and journal names

As you scroll through the list of articles in your search results, you should begin to notice that certain authors keep appearing. If you find an author that has written multiple articles on your topic, consider searching the AUTHOR field for that particular author. You can also search the web for that author’s Curriculum Vitae or CV (an academic resume) that will list their publications. Many authors maintain personal websites or host their CV on their university department’s webpage. Just type in their name and “CV” into a search engine. For example, you may find Michael Sherraden’s name often if your search terms are about assets and poverty. You can find his CV on the Washington University of St. Louis website.

Another way to narrow down your results is by journal name. As you are scrolling, you should also notice that many of the articles you’ve skimmed come from the same journals. Searching with that journal name in the JOURNAL field will allow you to narrow down your results to just that journal. For example, if you are searching for articles related to values and ethics in social work, you might want to search within the Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics. You can also navigate to the journal’s webpage and browse the abstracts of the latest issues.

Step 5: Examining references

As you begin to read your articles, you’ll notice that the authors cite additional articles that are likely relevant to your topic area. This is called archival searching. Unfortunately, this process will only allow you to see relevant articles from before the publication date. That is, the reference section of an article from 2014 will only have references from pre-2014. You can use Google Scholar’s “cited by” feature to do a future-looking archival search. Look up an article on Google Scholar and click the “cited by” link. This is a list of all the articles that cite the article you just read. Google Scholar even allows you to search within the “cited by” articles to narrow down ones that are most relevant to your topic area. For a brief discussion about archival searching check out this article by Hammond & Brown (2008): http://www.infotoday.com/cilmag/may08/Hammond_Brown.shtml. [2]

Step 6: Searching for systematic reviews and other sources

Another way to save time in literature searching is to look for articles that synthesize the results of other articles. Systematic reviews provide a summary of the existing literature on a topic. If you find one on your topic, you will be able to read one person’s summary of the literature and go deeper by reading their references. Similarly, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses have long reference lists that are useful for finding additional sources on a topic. They use data from each article to run their own quantitative or qualitative data analysis. In this way, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses provide a more comprehensive overview of a topic. To find these kinds of articles, include the term “meta-analysis,” “meta-synthesis,” or “systematic review” to your search terms. Another way to find systematic reviews is through the Cochrane Collaboration or Campbell Collaboration. These institutions are dedicated to producing systematic reviews for the purposes of evidence-based practice.

Putting it all together

Familiarizing yourself with research that has already been conducted on your topic is one of the first stages of conducting a research project and is crucial for coming up with a good research design. But where to start? How to start? Earlier in this chapter you learned about some of the most common databases that house information about published social work research. As you search for literature, you may have to be fairly broad in your search for articles. Let’s walk through an example. Dr. Blackstone, one of the original authors of this textbook, relates an example from her research methods class: On a college campus nearby, much to the chagrin of a group of student smokers, smoking was recently banned. These students were so upset by the idea that they would no longer be allowed to smoke on university grounds that they staged several smoke-outs during which they gathered in populated areas around campus and enjoyed a puff or two together.

A student in her research methods class wanted to understand what motivated this group of students to engage in activism centered on what she perceived to be, in this age of smoke-free facilities, a relatively deviant act. Were the protesters otherwise politically active? How much effort and coordination had it taken to organize the smoke-outs? The student researcher began her research by attempting to familiarize herself with the literature on her topic. Yet her search in Academic Search Complete for “college student activist smoke-outs,” yielded no results. Concluding there was no prior research on her topic, she informed her professor that she would not be able to write the required literature review since there was no literature for her to review. How do you suppose her professor responded to this news? What went wrong with this student’s search for literature?

In her first attempt, the student had been too narrow in her search for articles. But did that mean she was off the hook for completing a literature review? Absolutely not. Instead, she went back to Academic Search Complete and searched again using different combinations of search terms. Rather than searching for “college student activist smoke-outs” she tried, among other sets of terms, “college student activism.” This time her search yielded a great many articles. Of course, they were not focused on pro-smoking activist efforts, but they were focused on her population of interest, college students, and on her broad topic of interest, activism. Her professor suggested that reading articles on college student activism might give her some idea about what other researchers have found in terms of what motivates college students to become involved in activist efforts. Her professor also suggested she could play around with her search terms and look for research on activism centered on other sorts of activities that are perceived by some as deviant, such as marijuana use or veganism. In other words, she needed to be broader in her search for articles.

While this student found success by broadening her search for articles, her reading of those articles needed to be narrower than her search. Once she identified a set of articles to review by searching broadly, it was time to remind herself of her specific research focus: college student activist smoke-outs. Keeping in mind her particular research interest while reviewing the literature gave her the chance to think about how the theories and findings covered in prior studies might or might not apply to her particular point of focus. For example, theories on what motivates activists to get involved might tell her something about the likely reasons the students she planned to study got involved. At the same time, those theories might not cover all the particulars of student participation in smoke-outs. Thinking about the different theories then gave the student the opportunity to focus her research plans and even to develop a few hypotheses about what she thought she was likely to find.

Key Takeaways

- When identifying and reading relevant literature, be broad in your search for articles, but be narrower in your reading of articles.

- Conducting a literature search involves the skillful use of keywords to find relevant articles.

- It is important to narrow down the number of articles in your search results to only those articles that are most relevant to your inquiry.

Glossary

- Query- search terms used in a database to find sources

Image Attributions

Magnifying glass google by Simon CC-0

Librarian at the Card Files at Senior High School in New Ulm Minnesota by David Rees CC-0

No smoking by OpenIcons CC-0

- Figure 2.1 copied from image “Search operators” by TU Delft Libraries (2017). Shared using a CC-BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Retrieved from: https://tulib.tudelft.nl/searching-resources/search-operators/ ↵

- Hammond, C. C. & Brown, S. W. (2008, May 14). Citation searching: Searching smarter & find more. Computers in libraries. Retrieved from: http://www.infotoday.com/cilmag/may08/Hammond_Brown.shtml ↵