13.2 Qualitative interview techniques

Learning Objectives

- Identify the primary aim of in-depth interviews

- Describe what makes qualitative interview techniques unique

- Define the term interview guide and describe how to construct an interview guide

- Outline the guidelines for constructing good qualitative interview questions

- Describe how writing field notes and journaling function in qualitative research

- Identify the strengths and weaknesses of interviews

Qualitative interviews are sometimes called intensive or in-depth interviews. These interviews are semi-structured; the researcher has a particular topic about which she would like to hear from the respondent, but questions are open-ended and may not be asked in exactly the same way or in exactly the same order to each and every respondent. For in-depth interviews, the primary aim is to hear from respondents about what they think is important about the topic at hand and to hear it in their own words. In this section, we’ll take a look at how to conduct qualitative interviews, analyze interview data, and identify some of the strengths and weaknesses of this method.

Constructing an interview guide

Qualitative interviews might feel more like a conversation than an interview to respondents, but the researcher is in fact usually guiding the conversation with the goal in mind of gathering information from a respondent. Qualitative interviews use open-ended questions, which are questions that a researcher poses but does not provide answer options for. Open-ended questions are more demanding of participants than closed-ended questions for they require participants to come up with their own words, phrases, or sentences to respond.

In a qualitative interview, the researcher usually develops a guide in advance that she then refers to during the interview (or memorizes in advance of the interview). An interview guide is a list of topics or questions that the interviewer hopes to cover during the course of an interview. It is called a guide because it is simply that—it is used to guide the interviewer, but it is not set in stone. Think of an interview guide like your agenda for the day or your to-do list—both probably contain all the items you hope to check off or accomplish, though it probably won’t be the end of the world if you don’t accomplish everything on the list or if you don’t accomplish it in the exact order that you have it written down. Perhaps new events will come up that cause you to rearrange your schedule just a bit, or perhaps you simply won’t get to everything on the list.

Interview guides should outline issues that a researcher feels are likely to be important. Because participants are asked to provide answers in their own words and to raise points they believe are important, each interview is likely to flow a little differently. While the opening question in an in-depth interview may be the same across all interviews, from that point on, what the participant says will shape how the interview proceeds. This, I believe, is what makes in-depth interviewing so exciting–and rather challenging. It takes a skilled interviewer to be able to ask questions; listen to respondents; and pick up on cues about when to follow up, when to move on, and when to simply let the participant speak without guidance or interruption.

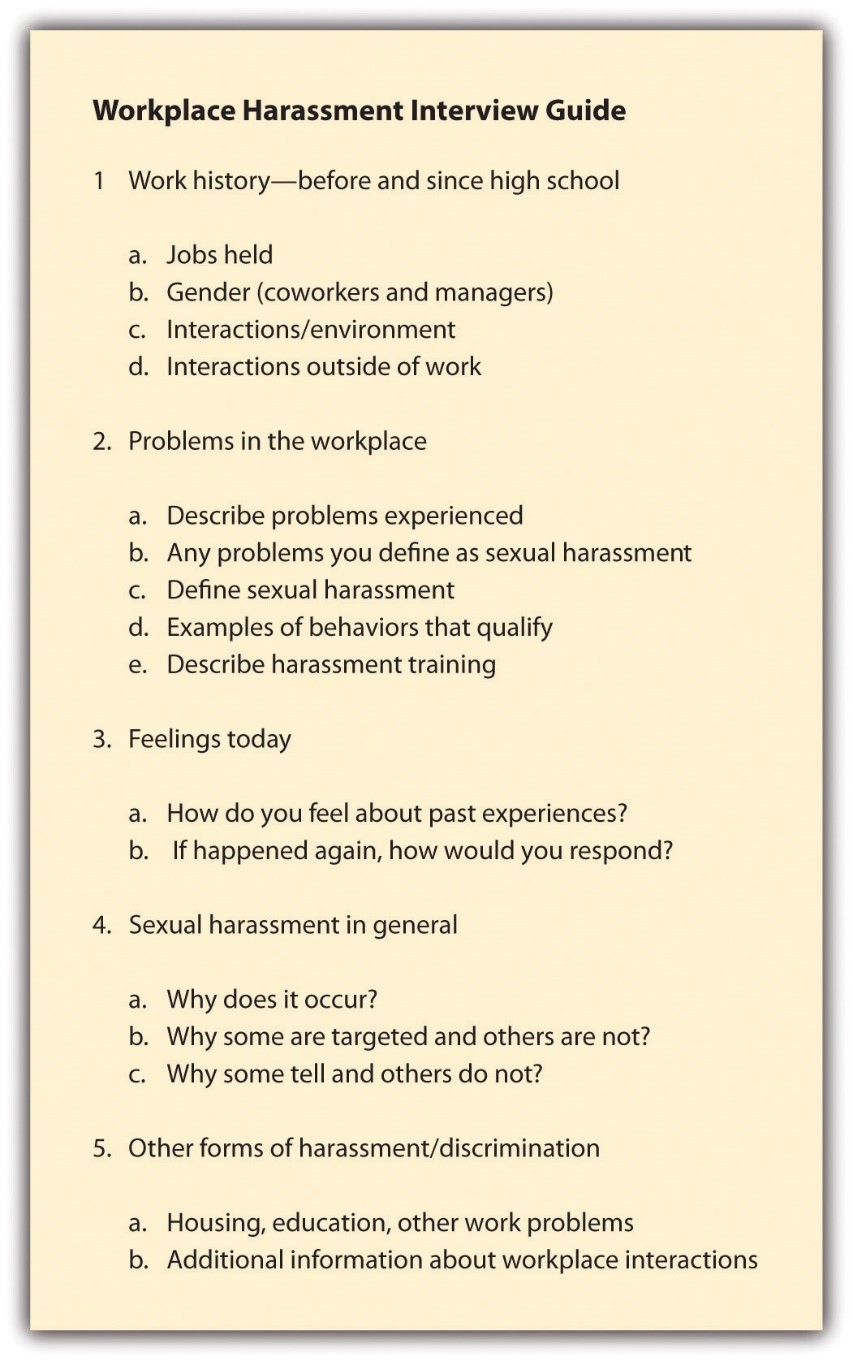

I’ve said that interview guides can list topics or questions. The specific format of an interview guide might depend on your style, experience, and comfort level as an interviewer or with your topic. Figure 13.1 provides an example of an interview guide for a study of how young people experience workplace sexual harassment. The guide is topic-based, rather than a list of specific questions. The ordering of the topics is important, though how each comes up during the interview may vary.

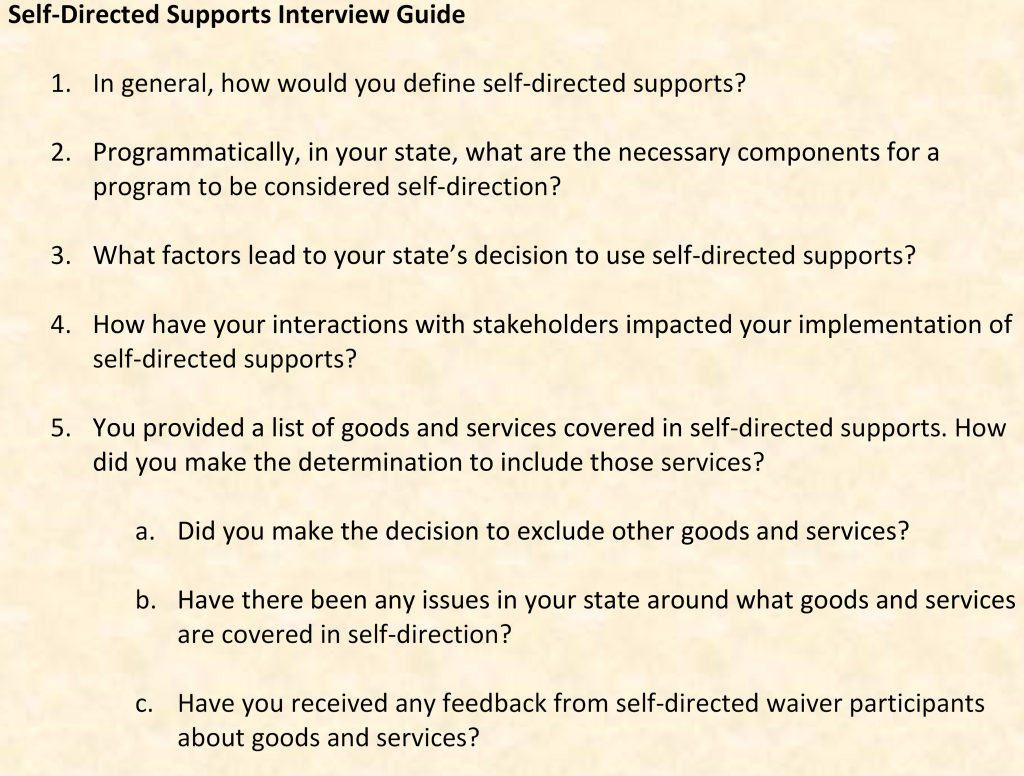

In my interviews with state administrators of developmental disabilities departments, the interview guide contained 15 questions all of which were asked to each participant. Sometimes, participants would cover the answer to one question before it was read. When I came to that question later on in the interview, I would acknowledge that they already addressed part of this question and ask them if they had anything to add to their response. Underneath some of the questions were more specific words or phrases for follow-up in case the participant did not mention those topics in their responses. These probes, as well as the questions, were based on our review of their department’s documentation about their programs. Our study was a challenging one in that administrators may have thought that since we were studying a particular kind of program, we may have an agenda to try and convince administrators to expand or better fund that program. We had to be very objective in how we worded questions to avoid the appearance of bias. Some of these questions are depicted in Figure 13.2.

As you might have guessed, interview guides do not appear out of thin air. They are the result of thoughtful and careful work on the part of a researcher. As you can see in both of the preceding guides, the topics and questions have been organized thematically and in the order in which they are likely to proceed (though keep in mind that the flow of a qualitative interview is in part determined by what a respondent has to say). Sometimes qualitative interviewers may create two versions of the interview guide: one version contains a very brief outline of the interview, perhaps with just topic headings, and another version contains detailed questions underneath each topic heading. In this case, the researcher might use the very detailed guide to prepare and practice in advance of actually conducting interviews and then just bring the brief outline to the interview. Bringing an outline, as opposed to a very long list of detailed questions, to an interview encourages the researcher to actually listen to what a participant is telling her. An overly detailed interview guide will be difficult to navigate during an interview and could give respondents the misimpression the interviewer is more interested in her questions than in the participant’s answers.

When beginning to construct an interview guide, brainstorming is usually the first step. There are no rules at the brainstorming stage—simply list all the topics and questions that come to mind when you think about your research question. Once you’ve got a pretty good list, you can begin to pare it down by cutting questions and topics that seem redundant and group like questions and topics together. If you haven’t done so yet, you may also want to come up with question and topic headings for your grouped categories. You should also consult the scholarly literature to find out what kinds of questions other interviewers have asked in studies of similar topics and what theory indicates might be important. As with quantitative survey research, it is best not to place very sensitive or potentially controversial questions at the very beginning of your qualitative interview guide. You need to give participants the opportunity to warm up to the interview and to feel comfortable talking with you. Finally, get some feedback on your interview guide. Ask your friends, other researchers, and your professors for some guidance and suggestions once you’ve come up with what you think is a strong guide. Chances are they’ll catch a few things you hadn’t noticed. Your participants may also suggest revisions or improvements, once you begin your interviews.

In terms of the specific questions you include in your guide, there are a few guidelines worth noting. First, avoid questions that can be answered with a simple yes or no. Try to rephrase your questions in a way that invites longer responses from your interviewees. If you choose to include yes or no questions, be sure to include follow-up questions. Remember, one of the benefits of qualitative interviews is that you can ask participants for more information—be sure to do so. While it is a good idea to ask follow-up questions, try to avoid asking “why” as your follow-up question, as this particular question can come off as confrontational, even if that is not your intent. Often people won’t know how to respond to “why,” perhaps because they don’t even know why themselves. Instead of “why,” I recommend that you say something like, “Could you tell me a little more about that?” This allows participants to explain themselves further without feeling that they’re being doubted or questioned in a hostile way.

Also, try to avoid phrasing your questions in a leading way. For example, rather than asking, “Don’t you think most people who don’t want kids are selfish?” you could ask, “What comes to mind for you when you hear someone doesn’t want kids?” Or rather than asking, “What do you think about juvenile offenders who drink and drive?” you could ask, “How do you feel about underage drinking?” or “What do you think about drinking and driving?” Finally, remember to keep most, if not all, of your questions open-ended. The key to a successful qualitative interview is giving participants the opportunity to share information in their own words and in their own way. Documenting decisions that you make along the way regarding which questions are used, thrown out, or revised can help a researcher remember during analysis the thought process behind the interview guide. Additionally, it promotes the rigor of the qualitative project as a whole, ensuring the researcher is proceeding in a reflective and deliberate manner that can be checked by others reviewing her study.

Recording qualitative data

Even after the interview guide is constructed, the interviewer is not yet ready to begin conducting interviews. The researcher next has to decide how to collect and maintain the information that is provided by participants. Researchers keep field notes or written recordings produced by the researcher during the data collection process, including before, during, and after interviews. Field notes help researchers document what they observe, and in so doing, they form the first draft of data analysis. Field notes may contain many things—observations of body language or environment, reflections on whether interview questions are working well, and connections between ideas that participants share.

Unfortunately, even the most diligent researcher cannot write down everything that is seen or heard during an interview. In particular, it is difficult for a researcher to be truly present and observant if she is also writing down everything the participant is saying. For this reason, it is quite common for interviewers to create audio recordings of the interviews they conduct. Recording interviews allows the researcher to focus on her interaction with the interview participant rather than being distracted by trying to write down every word that is said.

Of course, not all participants will feel comfortable being recorded and sometimes even the interviewer may feel that the subject is so sensitive that recording would be inappropriate. If this is the case, it is up to the researcher to balance excellent note-taking with exceptional question-asking and even better listening. I don’t think I can understate the difficulty of managing all these feats simultaneously. Whether you will be recording your interviews or not (and especially if not), practicing the interview in advance is crucial. Ideally, you’ll find a friend or two willing to participate in a couple of trial runs with you. Even better, you’ll find a friend or two who are similar in at least some ways to your sample. They can give you the best feedback on your questions and your interview demeanor.

Another issue interviewers face is documenting the decisions made during the data collection process. Qualitative research is open to new ideas that emerge through the data collection process. For example, a participant might suggest a new concept you hadn’t thought of before or define a concept in a new way. This may lead you to create new questions or ask questions in a different way to future participants. These processes should be documented in a process called journaling or memoing. Journal entries are notes to yourself about reflections or methodological decisions that emerge during the data collection process. Documenting these decisions is important, as you’d be surprised how quickly you can forget what happened. Journaling makes sure that when it comes time to analyze your data, you remember how, when, and why certain changes were made. The discipline of journaling in qualitative research helps to ensure the rigor of the research process—that is its trustworthiness and authenticity. We covered these standards of qualitative rigor in Chapter 9.

Strengths and weaknesses of qualitative interviews

As we’ve mentioned in this section, qualitative interviews are an excellent way to gather detailed information. Any topic can be explored in much more depth with interviews than with almost any other method. Not only are participants given the opportunity to elaborate in a way that is not possible with other methods such as survey research, but they also are able share information with researchers in their own words and from their own perspectives. Whereas, quantitative research asks participants to fit their perspectives into the limited response options provided by the researcher. And because qualitative interviews are designed to elicit detailed information, they are especially useful when a researcher’s aim is to study social processes or the “how” of various phenomena. Yet another, and sometimes overlooked, benefit of qualitative interviews that occurs in person is that researchers can make observations beyond those that a respondent is orally reporting. A respondent’s body language, and even their choice of time and location for the interview, might provide a researcher with useful data.

Of course, all these benefits come with some drawbacks. As with quantitative survey research, qualitative interviews rely on respondents’ ability to accurately and honestly recall specific details about their lives, circumstances, thoughts, opinions, or behaviors. As Esterberg (2002) puts it, “If you want to know about what people actually do, rather than what they say they do, you should probably use observation [instead of interviews].” [2] Further, as you may have already guessed, qualitative interviewing is time-intensive and can be quite expensive. Creating an interview guide, identifying a sample, and conducting interviews are just the beginning. Writing out what was said in interviews and analyzing the qualitative are time consuming processes. Keep in mind you are also asking for more of participants’ time than if you’d simply mailed them a questionnaire containing closed-ended questions. Conducting qualitative interviews is not only labor-intensive but can also be emotionally taxing. Seeing and hearing the impact that social problems have on respondents is difficult. Researchers embarking on a qualitative interview project should keep in mind their own abilities to receive stories that may be difficult to hear.

Key Takeaways

- In-depth interviews are semi-structured interviews where the researcher has topics and questions in mind to ask, but questions are open-ended and flow according to how the participant responds to each.

- Interview guides can vary in format but should contain some outline of the topics you hope to cover during the course of an interview.

- Qualitative interviews allow respondents to share information in their own words and are useful for gathering detailed information and understanding social processes.

- Field notes and journaling document decisions and thoughts the researcher has that influence the research process.

- Drawbacks of qualitative interviews include reliance on respondents’ accuracy and their intensity in terms of time, expense, and possible emotional strain.

Glossary

- Field notes- written notes produced by the researcher during the data collection process

- In-depth interviews- interviews in which researchers hear from respondents about what they think is important about the topic at hand in the respondent’s own words

- Interview guide- a list of topics or questions that the interviewer hopes to cover during the course of an interview

- Journaling- making notes of emerging issues and changes during the research process

- Semi-structured interviews- questions are open ended and may not be asked in exactly the same way or in exactly the same order to each and every respondent

- Figure 13.1 is copied from Blackstone, A. (2012) Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods. Saylor Foundation. Retrieved from: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_principles-of-sociological-inquiry-qualitative-and-quantitative-methods/ Shared under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/) ↵

- Esterberg, K. G. (2002). Qualitative methods in social research. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. ↵