5 Chapter Five: Accessing Sport

Section one: The fundamentals

A)

Exercise 1: Notebook Prompt

Many of you are likely familiar with the concept of “ability inequity,” which the authors of this article define as “an unjust or unfair (a) ‘distribution of access to and protection from abilities generated through human interventions’ or (b) ‘judgment of abilities intrinsic to biological structures such as the human body’.”

However, they go on to identify the following “ability concepts” that are less familiar:

1) ability security (one is able to live a decent life with whatever set of abilities one has)

2) ability identity security (to be able to be at ease with ones abilities)

How prevalent are these forms of security among disabled people you know? Or, if you identify as a disabled person, would you say your social surroundings and community foster and support these kinds of security? Furthermore, while the focus of the article is on Kinesiology programs, it is also important to reflect on how academia in general accommodates for disability. If you feel comfortable answering this question, what has been your experience of postsecondary education to date?

-OR-

The authors also observe that “Ableism not only intersects with other forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, ageism, and classism, but abilities are often used to justify such negative ‘isms’.”

What do you think this means? Provide an example.

|

Ability security ensures individuals can lead a dignified life regardless of their abilities, while ability identity security refers to feeling at ease with one’s abilities. In my experience, these forms of security are not consistently present for disabled individuals. Many struggle with environments that are not designed for accessibility, requiring them to advocate for accommodations that should be fundamental rights. While universities provide accommodations, the process is often bureaucratic and places undue burden on students. Stigma surrounding disability further discourages individuals from seeking support, affecting both their academic experience and self-perception. The idea that ableism intersects with other forms of oppression suggests that perceived (in)abilities are used to justify discrimination across race, gender, class, and age. In professional settings, disabled individuals often face hiring biases based on assumptions of reduced productivity. This intersects with classism, as employment barriers contribute to financial instability. Women with disabilities, especially women of color, experience compounded difficulties in accessing healthcare, education, and career advancement. A historical example is the eugenics movement, where individuals with disabilities, particularly from marginalized backgrounds, were institutionalized or sterilized under the guise of societal “fitness.” Similarly, racist and sexist ideologies have restricted access to education and employment based on perceived intellectual or physical inferiority. Addressing these inequities requires systemic change. Institutions must go beyond basic accommodations and cultivate environments where ability security and identity security are embedded within educational and professional frameworks, fostering true inclusivity. |

Exercise 2: Implicit Bias Test

Did anything surprise you about the results of the test? Please share if you’re comfortable OR comment on the usefulness of these kinds of tests more generally.

| Implicit bias tests are useful tools for raising self-awareness about unconscious associations we may hold. They can help individuals reflect on how these biases might influence decisions and interactions, especially in professional settings like education, healthcare, or sport. While not definitive measures of one’s character, they are valuable starting points for personal growth and broader conversations about equity. When combined with ongoing education and action, they can contribute meaningfully to more inclusive environments.

|

B) Keywords

Exercise 3:

Add the keyword you contributed to padlet and briefly (50 words max) explain its importance to you.

|

Keyword: Crip Theory I consider Crip Theory important in the sense that it upends traditional modes of thinking around disability by emphasizing the social and cultural landscapes within which disability is interpreted and lived. It provides a critical lens through which to analyze the ways sports simultaneously reinforce and subvert ableist norms, with the complexity of disability identity and representation at stake. |

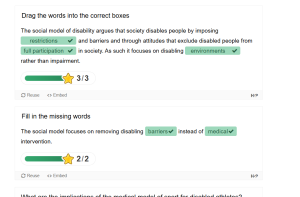

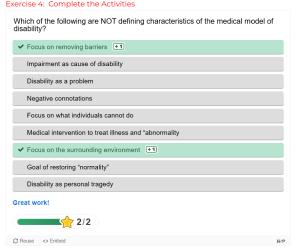

B) On Disability

Exercise 4: Complete the Activities

Exercise 5: Notebook Prompt

What do Fitzgerald and Long identify as barriers to inclusion and how might these apply to sport in particular?

Fitzgerald and Long (2017) identify several barriers to inclusion in sports and leisure, including physical and environmental barriers. These include poor or inaccessible sports facilities, venues, and equipment, which directly limit the participation of disabled and other marginalized groups. Until such fundamental infrastructure barriers are removed, equal participation is impossible.

Apart from infrastructure, social and cultural barriers also significantly affect inclusive participation. Negative stereotypes, stigma, and prejudiced views continue to exclude groups of individuals based on disability, ethnicity, gender, or sexuality. Such cultural biases are firmly entrenched in societal attitudes and form extremely large hurdles apart from physical accessibility.

Aside from social factors, institutional and structural barriers play a crucial role in perpetuating inequalities. Sports organizations tend to embody exclusionary governance policies and practices, which lead to unequal funding, discriminatory talent identification, and disproportionate representation in leadership positions. Such structural asymmetries assist in institutionalizing and legitimizing existing power asymmetries, and disadvantaged groups become even more disadvantaged.

Economic constraints pose an additional complexity for inclusion, with the expenses of involvement, such as membership fees, specialized equipment, and transportation, disproportionately affecting economically disadvantaged groups. The financial barriers, which are not always accounted for in policy discussions, actively work against equal access and participation in sports.

Finally, informational and educational barriers compound these problems. Inaccessibility to information, ineffective awareness campaigns, and a lack of targeted education programs further hinder marginalized groups from accessing full involvement in sports and leisure contexts. Addressing these interconnected barriers necessitates comprehensive, structural, and cultural reform at the sports institution, policy, and societal attitude level to achieve effective inclusion (Fitzgerald & Long, 2017).

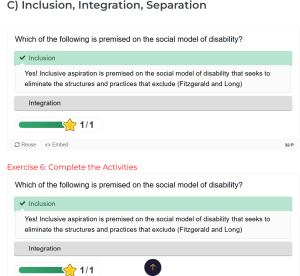

C) Inclusion, Integration, Separation

Exercise 6: Complete the Activities

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

Choose ONE of the three questions Fitzgerald and Long argue disability sport needs to address and record your thoughts in your Notebook.

- Should sport be grouped by ability or disability?

- Is sport for participation or competition?

- Should sport competitions be integrated?

| Should sports be graded on ability or disability?

Considering Fitzgerald and Long’s (2017) insightful question, according to my perception, sports should be graded according to ability and not necessarily by disability. Classifying athletes in terms of ability fosters equality and inclusiveness, allowing athletes to compete considerably at their own ability and performance levels. This approach focuses on what one can do rather than on what one cannot do. Nonetheless, practical realities should not be neglected: ability grouping requires skillful evaluation and the proper classification frameworks to avoid uneven competition. But while ability grouping is inclusive in theory, it also poses difficulties of ensuring that competitions are both fair and meaningful as well as correctly being able to judge abilities. There is the risk that overly general ability grouping may systematically penalize some athletes by failing to recognise specific impairments and needs accurately enough. Thus, while ability-based grouping aligns with inclusive values and advances positive representation, its proper use requires robust systems of classification and sensitivity together with frequent readjustment. The sports ought to pursue an ambidextrous balance, utilizing ability as its fundamental order principle while paying attention to and being attuned to disability-related contexts and necessities. Such a mixed model can be the most compelling avenue for real inclusion, forging equitable, fun, and significant experiences for players of any ability and profile.

|

Part Two: Making Connections

A) Gender, Sport and Disability

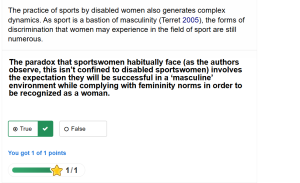

Exercise 8: Complete the Activity

The paradox that sportswomen habitually face (as the authors observe, this isn’t confined to disabled sportswomen) involves the expectation they will be successful in a ‘masculine’ environment while complying with femininity norms in order to be recognized as a woman.

True or false?

Take a moment to reflect on this paradox below (optional).

| I selected “True” because I recognize the paradox described by Fitzgerald and Long, where women athletes, especially disabled women, face conflicting expectations. Society pressures these athletes to succeed within sports that are traditionally seen as masculine, while also expecting them to maintain conventional standards of femininity to validate their identity as women. This dynamic creates a complex and challenging balance, as female athletes must constantly navigate between showcasing strength and conforming to stereotypical femininity norms. This paradox is evident in cases like Becky, the Paralympic Barbie, who challenges stereotypes about disability while also conforming to traditional feminine standards. |

B) Masculinity, Disability, and Murderball

Exercise 9: Notebook/Padlet Prompt

Watch the film, Murderball and respond to the question in the padlet below (you will have an opportunity to return to the film at the end of this module).

The authors of “Cripping Sport and Physical Activity: An Intersectional Approach to Gender and Disability” observe that the “gendered performance of the wheelchair rugby players can…be interpreted as a form of resistance to marginalized masculinity” (332) but also point out that it may reinforce “ableist norms of masculinity.” After viewing the film, which argument do you agree with?

a) Murderball celebrates a kind of resistance to marginalized masculinity

| d)

After viewing Murderball, I argue that the film both challenges and reinforces traditional norms of masculinity within disability sports. This dual perspective emerges from the complex portrayal of masculinity by the athletes, who navigate both societal expectations and their identity as men with disabilities. On the one hand, Murderball celebrates resistance to marginalized masculinity by portraying athletes as strong, assertive, and capable, both on and off the court. The film challenges stereotypes that label disabled men as weak, dependent, or asexual. Instead, athletes openly discuss their sexuality, relationships, and desire for independence, demonstrating agency and rejecting perceptions of passivity. For instance, players train rigorously, display physical prowess, and exhibit competitiveness, thus redefining masculinity in a way that includes men with disabilities. This is evident in scenes where Mark Zupan and his teammates emphasize their resilience and passion for the sport, breaking away from the conventional narrative of disabled men as fragile or helpless. However, the film also reinforces ableist norms of masculinity by focusing on traits traditionally associated with hegemonic masculinity, such as aggression, dominance, and physical strength. The portrayal of wheelchair rugby as a violent, full-contact sport suggests that masculinity is inherently linked to physical power. Furthermore, the athletes often engage in trash-talking and emphasize their sexual conquests, reinforcing the idea that masculinity is affirmed through toughness and dominance. This perspective risks alienating men who express masculinity differently or cannot conform to such physical standards. Therefore, Murderball simultaneously resists and reinforces dominant masculinity norms, highlighting the tension between empowerment and the persistence of hegemonic ideals within disability sports.

|

Section Three: Taking a Shot

A) Resistance

Richard, Jonceray, and Duquesne (2024) employ Crip Theory to analyze resistance to ableism and heteronormativity in sport. They discuss two broad forms of resistance in the context of disability sports.

The first form of resistance is located within the (para)sport itself and the normative frameworks that govern it. This type of resistance is resistance to dominant ableist discourses from within mainstream sporting frameworks. For instance, athletes who participate in Paralympic sports resist society’s belief that physical disability equates with inability. Through their performance in competitive arenas traditionally exclusive to able-bodied athletes, they resist exclusionary tradition and redefine what an athlete is. Internal resistance works here by employing the same structures to counter expectations and affirm the legitimacy of disabled athletes within mainstream sports arenas.

The second form of resistance is the creation of alternative, more marginal spaces, which are counterhegemonic. Within these spaces, nonconforming expressions of ability and identity in sports can occur. A few examples include grassroots disability sports or community-based initiatives that focus on inclusivity and reformulate sporting success outside of the conventional competition model. These spaces encourage a more fluid understanding of athleticism and resist the rigid categorization of ability and disability.

Lynch and Hill’s (2021) study of elite female wheelchair tennis players illustrates that disabled sports environments are less normative than able-bodied environments. The ensuing flexibility and diversity within these environments allow for more fluid and dynamic constructions of gender and ability than the rigid structures of mainstream sports. Through the facilitation of internal and alternative resistance, disability sports challenge current norms and advocate for more inclusive and equitable practices.

B) Calling out Supercrip

Exercise 10: Mini Assignment (worth 5% in addition to the module grade)

1) Do you agree with the critique of the “supercrip” narrative in this video? Why or why not? Find an example of the “supercrip” Paralympian in the 2024 Paris Paralympics or Special Olympics coverage and explain how it works.

|

I agree with the critique of the “supercrip” narrative as presented in the video “We’re the Superhumans” from the Rio Paralympics 2016. The “supercrip” narrative often portrays disabled athletes as inspirational solely because they have overcome their impairments to achieve athletic success. This framing, while seemingly positive, inadvertently perpetuates ableist norms by suggesting that disability needs to be transcended or defeated to gain societal acceptance. It positions disabled athletes as exceptional and heroic solely for their ability to compete, rather than recognizing their athletic achievements on equal terms with able-bodied athletes. An example from the 2024 Paris Paralympics is the portrayal of swimmer Ellie Challis, celebrated for her athletic prowess and “overcoming” her disability. The media emphasis on her resilience and triumph over adversity, rather than her skill and dedication as an athlete, exemplifies the supercrip narrative. Such representation shifts focus from athleticism to the perceived challenge of disability, reinforcing the idea that disabled individuals are valuable only when they exceed normative expectations. This narrative fails to challenge systemic ableism and instead valorizes individual perseverance while ignoring broader structural barriers. The focus should shift from portraying disability as a limitation to recognizing athletic talent without emphasizing overcoming adversity. |

2) Does the film Murderball play into the supercrip narrative in your opinion? How does gender inform supercrip (read this blog for some ideas)?

(300 words for each response)

|

Murderball partially plays into the supercrip narrative by portraying wheelchair rugby athletes as heroic for not allowing their disabilities to define them. The film emphasizes their toughness, competitiveness, and refusal to be pitied, which aligns with the supercrip trope. The athletes’ stories are framed around how they defy societal expectations, demonstrating resilience and determination to excel in a physically demanding sport despite their impairments. However, the film also complicates this narrative by emphasizing the athletes’ humanity beyond their disabilities. Unlike typical supercrip portrayals, Murderball does not reduce the athletes to mere symbols of inspiration. Instead, it presents them as complex individuals who are unapologetically competitive and aggressive. This nuanced portrayal challenges the idea that disabled individuals must be either pitiable or heroic. Gender also informs the supercrip narrative, as male athletes in Murderball are portrayed as hypermasculine to counter assumptions of weakness. This reinforces ableist masculinity by suggesting that to be accepted, disabled men must exhibit heightened toughness and aggression. Thus, while Murderball resists simplistic supercrip portrayals by depicting disabled athletes as multidimensional, it still upholds certain elements by framing athletic success as a triumph over disability, particularly through a masculine lens.

|

The film Murderball offers a model of resistance to gender and disability norms in its representation of athletes who reject traditional scripts of dependence, fragility, and submissiveness associated with disability. The athletes in the film do not fit into the passive or pitiful roles that disabled individuals are so frequently placed in. Instead, they present an aggressive, brazen, and physically tough image that challenges assumptions about what individuals with disabilities are or can be. This aligns with the idea of internal resistance discussed earlier in this notebook as in resisting ableist expectations from within mainstream sports structures by reconstituting what sporting excellence looks like.

The film also disrupts gender norms in demonstrating that masculinity in disability contexts does not have to conform to hegemonic ideals in conventional ways. While the film brings strength and dominance to the fore, it simultaneously creates space for less overt expressions of masculinity. The sportspeople speak openly about their weaknesses, relationships, and emotional lives, suggesting that strength and emotional complexity are not incompatible. This is particularly relevant in light of Fitzgerald and Long’s exploration of the paradox faced by women in sports, and the hypermasculine requirement placed on male athletes in able-bodied and disabled sports.

Murderball also falls into the supercrip trope, yet rather than simply perpetuating it, the film complicates it by including the athletes’ daily lives and struggles beyond their physical accomplishments. This complication challenges the binary of being seen as inspirational heroes or social burdens, reflecting the broader call for ability identity security outlined above. Just as Richard, Jonceray, and Duquesne emphasize the need for alternative and inclusive sporting spaces, Murderball offers a space where disability and masculinity are not constructed as binary opposites but as complicated, fluid identities. By resisting normative expectations in this way, identity and athleticism can be remade in disability sports.