14 Safe Sport and Hockey

Taylor McKee

Themes

Hockey Culture

Abuse and Violence

Safe Sport Policy

Learning Objectives

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

L01 Explore the conditions and context that have informed Canadian hockey culture and its historical relationship with Safe Sport initiatives;

L02 Identify the unique organizational and administrative challenges facing Safe Sport initiatives in hockey today;

L03 Define and interrogate hockey’s culture of silence as a barrier to implementing Safe Sport policies; and

L04 Investigate how hockey violence complicates or challenges commitments to Safe Sport.

Overview

This chapter explores the historical and contemporary relationship between Canadian Hockey Culture and Safe Sport policy. Throughout its history in Canada, hockey has held a privileged position as a beloved national pastime, a monocultural institution, a cherished symbol of Canadian identity, and a self-governing sporting body. Because Safe Sport requires constant scrutiny and openness, while hockey is predicated on traditionalism and insular governance, the two concepts have been historically incongruous. Resultantly, hockey’s bureaucratic structures, on-ice violence, and culture of silence have historically thwarted Safe Sport efforts. As long as Canadian Hockey Culture is empowered to internally adjudicate abuses, Safe Sport policies will continue to face resistance.

Key Dates

Hockey as Canadian Sporting Benchmark

There is little debate that hockey stands distinct and singular within the landscape of Canadian professional and semi-professional sport. Canada boasts seven National Hockey League (NHL) franchises, 51 Canadian Hockey League (CHL) franchises, six American Hockey League (AHL) franchises, two East Coast Hockey League (ECHL) franchises, and dozens of semi-professional teams scattered in leagues across the nation.

However, those that are paid to play represent merely the minute tip of a massive participatory pyramid in Canadian sport. Hockey Canada is “the national governing body for grassroots hockey in the country … [that] works in conjunction with the 13 member branches, the Canadian Hockey League and U Sports in growing the game at all levels.”[1] As of the 2023-24 season, they claim to have over 589,000 registered participants in Canada.[2] This means that approximately 1% of all Canadians are currently enrolled in formal hockey programs across the country.

While this suggests a staggering amount of interest in the game, the sheer enrollment numbers are not the sole measure of investment that Canadians have in youth hockey. In registration costs alone, based on data from 2011-12, Canadians may have spent $660,000,000 purely on registration fees for hockey in 2022-23,[3] though that number is likely much higher given the rate of registration inflation from 2011-12.[4] This is in no way a complete accounting of hockey’s vast cost including equipment, which pushes some estimates to an average cost of more than $5000 per family annually, or for an approximate total of $2,750,000,000 in annual spending, given Hockey Canada’s enrollment numbers.[5]

What draws so many to spend so much? Hockey’s place as a preeminent cultural signifier gives many the sense that participating in hockey is a form of cultural citizenship: “Developing as a hockey fan becomes akin to developing as a Canadian for many, and participation in the rituals and discourses of fandom plays a significant role in developing national identity, for individual and country alike.”[6]

Ensuring that those who register and play hockey receive a safe, edifying, and rewarding experience is the challenge levied at the thousands of sport volunteer administrators in hockey organizations across Canada, the overwhelming majority of which are under the jurisdiction of Hockey Canada.

The Current State of Play

In October 2022, following a summer wracked with scandal that forced several key resignations, interim board chair of Hockey Canada Andrea Skinner testified before a standing committee on Canadian Heritage. Staunchly defending her organization, Skinner insisted that “suggesting that toxic behaviour is somehow a specific hockey problem, or to scapegoat hockey as a centrepiece for toxic culture is, in my opinion, counterproductive to finding solutions…It risks overlooking the change that needs to be made more broadly to prevent and address toxic behaviour, particularly against women.”[7]

In response, Canadian MPs subjected Skinner and former Hockey Canada board chair Michael Brind’Amour to hours of terse questions, many of which expressed doubt regarding Hockey Canada’s leadership, decision-making. Skinner and Brind’Amour, continued to insist that Hockey Canada was the victim of “substantial misinformation and unduly cynical attacks” from the media.[8]

How did Hockey Canada find itself in this position of having its Safe Sport conduct firmly in the crosshairs of Canadian lawmakers, jeopardizing lucrative and long-standing corporate partnerships?

Moreover, how does a National Sport Organization (NSO), one that receives millions of dollars in funding from the Canadian government, feel emboldened enough in their own institutional authority that they adopt such a firm stance when questioned by Members of Parliament?

To answer these questions, a broader context of Canadian hockey and Safe Sport must be considered.

The Strength of Canadian Hockey: Organization

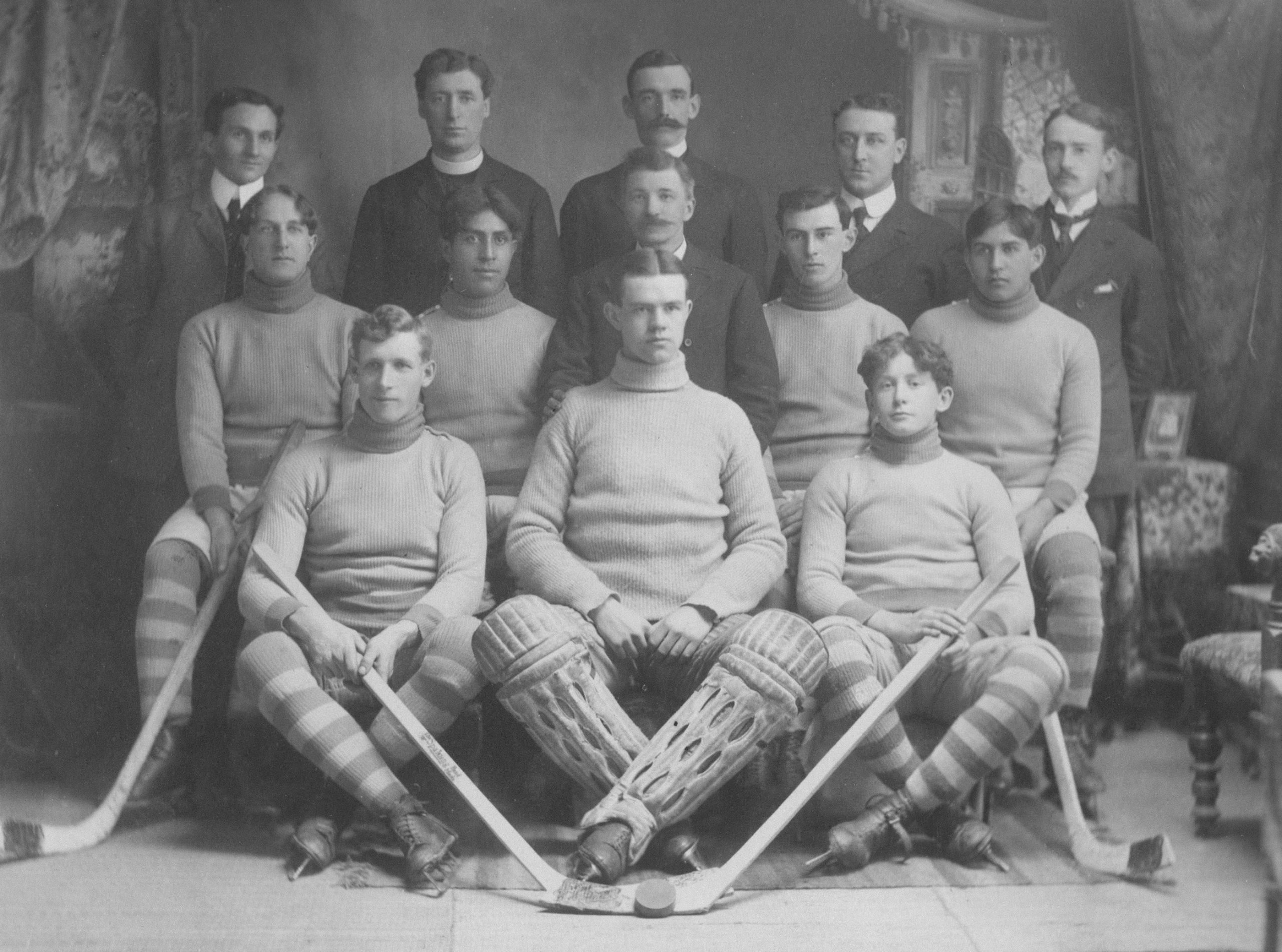

The structure of hockey, itself a product of middle-class society in North American urban environments, is in many ways defined by organized and standardized play.[9] Beginning with the first organized game played in 1875 in Monreal, the “cradle of organized sport” in Canada, hockey was organized and re-organized, standardized and re-standardized, depending on unique geographic and socioeconomic conditions.[10]

Richard Gruneau and David Whitson offer a valuable characterization of the debate surrounding hockey’s origin in Canada and its relationship to the game’s institutional and organizational origins: “There is little point in engaging in debate about which folk game, played where, or when, is the true precursor to the modern game of hockey. The real origins of the game as we know it are synonymous with the beginning of hockey’s institutional development.”[11]

Hockey’s strength as a Canadian institution is directly related to its ability to create strong, effective governance structures in the amateur, professional, and minor levels of the game throughout the early years of Canadian sport history. The endurance of these institutions can be further attributed to formal relationships forged with other groups and individuals, including all levels of government, private institutions, and individual benefactors.

While hockey in Canada is made possible through nonprofit and charitable efforts, the sport is explicitly marked by its elite origins and persisting exclusivity as the pastime of those who can afford to participate. Canadian hockey history and Canadian elite society remain inextricably linked: written into the game’s regulations, stitched onto banners, and etched into the game’s most sacred surfaces.

For example, the NHL’s Stanley Cup is named after Lord Stanley of Preston, who donated the cup to be awarded to Canada’s top amateur hockey team in 1893.[12] In 1886, one of the most prominent governing bodies in Canadian hockey was the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada, founded in part by Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Hugh Andrew Montagu Allan, who later donated a cup to be given to Canada’s top amateur hockey club following a decision to allow professional clubs to win the Stanley Cup. The Allan Cup is still awarded today to Canada’s top senior men’s team.

Prior to 2010, the NHL award for most valuable player (MVP), as voted by players, first awarded in 1971, was named after former Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson. Other contemporary NHL awards, such as the Norris Trophy, William Jennings Trophy, and Selke Trophy are named after prominent businessmen who helped shape the organizational structure of the modern NHL, cementing their importance as administrators onto the permanent landscape of modern hockey.

The modern Canadian hockey player discourse and debates over who is the best defensive forward, goalie, MVP, and even the NHL’s ultimate champion, are all imbued with the names of famed administrators, industrialists, and organizers. It seems apparent that a sport with such a long legacy of celebrated organization would develop an ethos, both in the professional and amateur ranks, of confidence regarding its ability to conduct its own affairs. Hockey was historically free from major regulatory influence, especially given that many of the game’s early administrators were directly connected to the corridors of Canadian power.

This is the backdrop against which the modern Safe Sport crisis in hockey is set. It is not out of an abundance of incompetent bureaucrats and newfangled rule changes, but instead hockey’s history in Canada as defined by its ability to govern and police itself.

Self-Reflection

One of the most important expressions of class division in Canadian sport during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is the question of amateurism versus professionalism. The history of amateurism and professionalism in Canadian sport highlights the struggle between those who believed that sport should be played for intangible, esoteric reasons, such as the love of competition or pride in one’s town, and those who believed that participation in organized sport was a form of labour and therefore subject to equitable compensation.

Gruneau and Whitson summarize sociological differences between the two perspectives, by characterizing the relationship between leisure time and amusement:

By the turn of the century a clear distinction between the rational use of leisure time and seemingly irrational amusement had become fully institutionalized in Canada. Rational recreation was promoted in amateur sports organizations, schools, municipal parks, and libraries. Irrational leisure – typically associated with drinking, gambling, and ‘rough’ sport – was patrolled by the police. Amateur hockey was championed as a form of rational recreation, and its emerging rules and organizational structures were largely in the grip of the moral entrepreneurs.[13]

The “moral entrepreneurs” referred to by Gruneau and Whitson are the businessmen and professionals who comprised the English-speaking, white, middle-class, elite athletes. These men, champions of “moral propriety and self-improvement,” represented the vanguard of amateur sport in Canada.[14]

However, McKinley puts it more directly in describing the ideological underpinning of Canadian amateur hockey’s forefathers: “Canada’s amateur athletic clubs were forged in the smithy of British Victorian idealism, in which gentlemen engaged in sport for the honour of competition.”[15]

McKinley maintains that the ideal of amateurism reflected “British” design: an antiquated notion of honourable conduct imported from overseas.

- How do you think hockey’s origin as an amateur game influencedthe structure it demonstrates today?

- Do you believe the lack of regulation in the early years of hockey development plays a role in the current Safe Sport issues the game faces? Why? Why not?

- To what extent do historical perceptions of masculinity in hockey affect efforts to addressthe current Safe Sport issues the game faces?

Hockey Culture and the Sanctity of Silence

Often, when discussing regulating practices inside of hockey spaces, specifically as it relates to Safe Sport policies, team officials and players will express trepidation. Many are uneasy when attempting to alter behaviours, practices, and traditions from inside hockey’s most sanctified area: the dressing room. No location is more stringently and carefully administered, often by a mixture of dogma, oral tradition, and pop psychology, than the dressing room. Former NHL captain Brad Marsh wrote:

If you ask any retired athlete what they miss most about the game, the answer quite often will be his teammates and the atmosphere of the dressing room. The two things go hand in hand. From my point of view, however, the interaction within the dressing room is the key. This is the common denominator that binds any team together. Having a strong, confident, yet still relaxed atmosphere in the room is the foundation to being successful as a team. Everyone needs to feel like he belongs, is valued and is welcomed. In turn, each player must feel responsible not only for himself but answerable to everyone else in the room … Over the years, the rooms themselves have changed. What has not changed is the notion that the dressing room is a sacred place is still the same today as it was all those years ago.[16]

This is a common refrain for players, coaches, and team officials when discussing the hockey dressing room. It is not simply an area to discuss tactics, prepare equipment, and rest between periods; The dressing room is a social bonding space, where players are free to be vulnerable and express brutal honesty.

Teams may have special rules regarding where you may step, where players sit, who may exit the room in a specific order, and even what age parents are to stop from entering to help players tie their skates.[17] Undoubtedly, some of these practices amount to simply superstition common in many sporting environments.

Video 14.1 Don’t Step On The Logo – NHL Dressing Room Protocol

GeoSports. (2014, February 17). Don’t Step On The Logo– NHL Dressing Room Protocol [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aBTqigT35xc. [Transcript]

However, it is important to highlight the ways in which hockey presents unique challenges for Safe Sport advocates and dressing room culture is a consistently complicating factor. Throughout the past decades, hockey dressing room conduct has been the subject of urban legends, disturbing rumours, and serious criminal offences. Practices such as “cage raging,” where young players engage in hand-to-hand combat with their helmets and gloves on have straddled the line between harmful hazing ritual and playful gameplay and have been outlawed in many hockey jurisdictions.[18]

It is assumed by many participants, perhaps erroneously, that the rituals inside of the actual dressing room are protected by a notion of secrecy shared by teammates. However, it seems as though actions performed by members outside of the dressing room feel the protections of the dressing room extend outside the physical hockey space and into their personal lives.

In Practice:

Navigating Risk

Hockey presents an especially challenging Safe Sport context because some violence and rough play are sanctioned as part of the game itself. But while many sports involve physicality that can result in injury, it is important for us to observe and respect the agreed-upon levels of risk associated with participation in that sport.

For example, while body checking may be acceptable on the ice, the same action outside the context of a hockey game is no longer permissible. As sport participants, we need to ensure that our behaviors or actions are appropriate to the situation, safe, and consented to by everyone involved.

This means understanding the important role that context plays, since in-game actions, such as fighting, are inappropriate off the ice. This can lead to confusion and unclear distinctions between acceptable and unacceptable conduct.

The culture of silence that has inculcated Canadian hockey players presents substantial challenges for Safe Sport policy makers and sport administrators seeking to eradicate abuse, bullying, and harassment in sport at the youth sport level.[19] But even at the highest levels of organized hockey, the dressing room is a space where safety is not guaranteed. In October 2021, former Chicago Blackhawk Kyle Beach came forward as one of the accusers in a lawsuit against former video coach Brad Aldrich. The accusers alleged that Aldrich “groomed, harassed, threatened and assaulted” them during the 2010 NHL postseason, a season in which the Blackhawks won the Stanley Cup. Shortly after the incident took place, Beach contacted the leadership of the Blackhawks to notify them of the incident.[20]

For three weeks, the Blackhawks failed to act. An independent investigation into the incident produced a disturbing timeline of events in which the Blackhawks willingly allowed Aldrich to remain around the team after learning of the alleged assault, including having close contact with Beach, known in the report as John Doe:

From May 23, 2010, until June 14, 2010, Aldrich continued to serve as the Blackhawks’ video coach, traveled with the team to Philadelphia for games in the Stanley Cup Finals, and otherwise participated in team activities. The Black Aces, including John Doe, continued to practice and watch playoff games, and traveled to Philadelphia for Game 6, the last game of the Stanley Cup Finals. We found no evidence that steps were taken to learn more about the incident involving Aldrich or to discuss the issue with John Doe or with Aldrich. We found no evidence that there were discussions about whether it was appropriate, based on the information known at the time, to limit Aldrich’s contacts with Black Aces, Blackhawks players, or Blackhawks personnel. We found no evidence that the Blackhawks’ Human Resources Department was contacted about the incident, that an investigation was initiated, or that any other steps were taken to pursue the information known at the time.[21]

Aldrich signed the separation agreement, accepted positions at Notre Dame University, Miami University – where he resigned after being accused of sexual assault – and then as a High School coach in Michigan, where he was convicted of sexual contact with a minor and served nine months in prison.[22]

There is little doubt that Aldrich’s association with the Blackhawks enabled him to receive further hockey opportunities, including ones that gave him access to coaching minors. The Blackhawks, unquestionably one of the NHL’s most successful franchises from 2009-15, won three Stanley Cups. The 2010 Stanley Cup, which had Aldrich’s name etched onto its surface, now features a gnarled set of XXXXXs, a permanent attempt to erase this incident from hockey’s collective memory.[23]

Inattention and inaction on the part of the Blackhawks permanently scarred the most valued item in professional hockey, but the cosmetic damage to the trophy is far from the most destructive legacy. The Blackhawks settled the 2021 lawsuit out of court. In February 2022, Blackhawks owner Rocky Wirtz provided a fitting bookend to a story marked by secrecy and a lack of transparency. When questioned for the first time after the story was broken, Wirtz, who was visibly enraged, stated:

What we’re going to do today is our business, I don’t think it’s any of your business…You don’t work for the company…If someone in the company asks that question, we’ll answer it,’ Wirtz continued. ‘And I think you should get on to the next subject. We’re not going to talk about Kyle Beach, we’re not going to talk about anything that happened. Now we’re moving on, what more do I have to say? Do you want to keep asking the same question, and hear the same answer?’[24]

From a Safe Sport perspective, it most certainly is the business of anyone in a position of authority to provide transparency, leadership, and strength of conviction when faced with a matter as serious as the one with which the Blackhawks were presented in spring 2010. Allowing a pervasive culture of silence to permeate the dressing room and the boardroom has seriously deleterious consequences for professional, amateur, and youth sports organizations.

Perhaps the most pressing lesson that can be learned from the Blackhawks example is the ubiquity of abuse in the sport of hockey. If it can occur in the most tightly controlled, well-regulated, and, as Marsh described it, “sacred,” hockey environments in the world, it can certainly be found at community rinks, campuses, and wherever hockey is played.[25]

Hockey Culture and Safe Sport

A critical, central tenet of the Safe Sport process is a commitment to transparency and a commitment to constant evaluation and re-evaluation. Moreover, as Catherine Ordway argues, ethical leadership in sport requires transparency as well: “Authentic leaders and their relationships with their stakeholders are characterised by ‘transparency, openness and trust; guidance toward worthy objectives; and an emphasis on follower development.’”[26]

The challenges faced over the historical development of Safe Sport are numerous and protean.[27] Therefore, the purveyors of modern Safe Sport must hold sport organizations accountable to Safe Sport obligations, including their obligations to revise and evaluate their policies and practices. Hockey’s, pervasive culture of secrecy, ritual, and coercion, is fundamentally incongruous with the principles of transparency required for Safe Sport delivery.[28]

Counterpoint:

Boundaries of Rough Play

In recent years, many examples of violence, abuse, and injury in Canadian hockey have come to light through high-profile cases. But while many of these instances took place off ice, including the 2018 IIHF World Junior Championship Abuse Scandal, countless others have taken place in plain view during games. These innumerable injuries have affected participants at every age and level of play, often resulting from fighting and other forms of rough play.

- Given our commitment to Safe Sport, and the desire to preserve the physical and emotional wellbeing of hockey participants, should efforts be made to eliminate violence within the game, including fighting and hitting?

- How far should interventions go to ensure the health and safety of participants, and what constitutes an acceptable level of risk?

Video 14.2 Hockey Culture Solutions & Strategies

Video provided by Dr. Taylor McKee, Host and Moderator, Centre for Sport Capacity, Brock University. Used with permission. [Transcript]

North American hockey institutions have long been inundated by accusations and prosecutions relating to maltreatment, abuse, bullying, hazing, and a host of other Safe Sport violations. Scholar Laura Robinson, the author of 1998’s Crossing the Line: Violence and Sexual Assault in Canada’s National Sport, wrote in 2015 of “hockey’s rape culture,” which included a cursory review of a half dozen assault cases before the courts or under investigation at the time of her publishing.[29]

CBC noted that there have been 47 publicly reported cases where “young hockey players were charged with sexual assault.”[30] However, there is no comprehensive record of each individual assault, harassment, hazing, or bullying case, investigation, or accusation, ongoing or historical, that involves hockey players and hockey teams in Canada.

Video 14.3 Why the sexual assault conviction rates appears lower for hockey players

CBC News: The National. (2024, February 4). Why the sexual assault conviction rates appears lower for hockey players [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DvyuEwbwgr4. [Transcript]

Though the 2018 World Junior Team sexual assault scandal may not be strictly a Safe Sport issue in the eyes of many hockey observers, the questions raised by the incident have many important implications for hockey culture as a whole. Hockey, atop the pedestal of Canadian sporting infrastructure thanks in large part to the vast organizational resources committed to its maintenance, sets the agenda for much of Canadian sport.

As such, the 2018 scandal revealed uncomfortable truths regarding Canadian sport and sexual assault. As Fogel and Quinlan argue, “Within the Canadian sport system, sexual assault is tolerated and even in some cases promoted as part of a competitive, hierarchical culture of masculine violence.”[31] Whether it is representative of Canadian sport as a whole or not, Canadian hockey institutions must acknowledge the erosion of public trust stemming from the multitude of scandals facing the sport as a whole and work to ensure the sport is made safer for players of all abilities and ages.

Safe Sport initiatives comprised a substantial part of hockey league responses to the 2018 World Junior team scandal, despite staunch denials from influential hockey figures that hockey’s culture needs fixing. NHL commissioner Gary Bettman insisted that:

This is not representative, these allegations, of what takes place in our game and we’re committed to setting the right example and cooperating with hockey organizations at all levels, particularly the youth level, to make sure the message of what is appropriate conduct is delivered…We want people to know that our games is inclusive, welcoming and safe.[32]

However, these claims that instances of abuse are not representative of “what takes place in our game,” the public revelation of these allegations prompted some hockey organizations to implement or improve their Safe Sport policies.

Major Canadian hockey institutions have undertaken numerous new measures in an attempt to incorporate Safe Sport principles in the governance and practices of their organizations. For example, Hockey Canada’s website features a suite of policies addressing maltreatment, gender expression, dressing room policies, and a link to an independent third party reporting mechanism for complaints related to maltreatment.[33]

Furthermore, the AHL, CHL, ECHL, Professional Women’s Hockey League (PWHL), and United States Hockey League (USHL) have created an initiative called “the Respect Hockey Culture Center – a centralized platform that provides access for players, coaches, and employees to confidentially receive mental health support services and to report on incidents of bullying, abuse, harassment, and discrimination.”[34]

These initiatives, programs, and policies are evidence that Safe Sport is a substantial and serious issue for those in corridors of hockey’s most powerful spaces.

Further Research

The relationship between hockey and Safe Sport policies is necessarily contingent and evolving, requiring further research. For example, although this chapter introduces the question of how on-ice violence challenges the ideals of Safe Sport, this topic requires further interrogation regarding the adjudication of violent gameplay and the possible links between on- and off-ice infractions.

Additionally, although Canadian hockey culture is often a monolithic institution defined by its uniformity and homogeneity, additional research into specific geographic contexts, teams, leagues, levels of play, and across gender can reveal important distinctions that will inform how Safe Sport policies should be developed and enacted moving forward.

Key Terms

Suggested Assignments

- Policy Analysis:

-

Look up and review a specific Safe Sport policy currently employed by a Canadian hockey organization (for example, Hockey Canada’s “Dressing Room Policy” or “Maltreatment Complaint Management Policy”).

- Create a brief summary of the policy, highlighting any key takeaways or background provided.

- Provide your own critical assessment of any potential strengths or weaknesses you perceive in this Safe Sport policy.

2. Policy in Practice:

-

Research into a specific Safe Sport issue or infraction from Canadian hockey.

- What occurred and what was the response to this incident?

- Who was affected?

- Who was responsible for determining how the issue was handled and what was the adjudication process?

- What were the resulting consequences?

- From the perspective of Safe Sport, what is your view of how this situation was handled?

Further Reading

Allingham, J. (2019). Major misconduct: The human cost of fighting in hockey. Arsenal Pulp Press.

Cormack, P., & Cosgrave, J. F. (2013). Desiring Canada: CBC contests, hockey violence, and other stately pleasures. University of Toronto Press.

Donnelly, P., & Harvey, J. (2007). Social class and gender: Intersections in sport and physical activity. In K. Young & P. White (Eds.), Sport and gender in Canada (pp. 49-68). Oxford University Press.

Hardy, S., & Holman, A. C. (2018). Hockey: A global history. University of Illinois Press.

Kidd, B. (1996). The struggle for Canadian sport. University of Toronto Press.

Lorenz, S., & Osborne, G. (2009). Brutal butchery, strenuous spectacle: Hockey, violence, and manhood and the 1907 season. In J. C.-K. Wong (Ed.), Coast to coast: Hockey in Canada to the Second World War (pp. 105-124). University of Toronto Press.

Poulter, G. (2013). Embodying nation: Indigenous sports in Montreal 1860-1885. In Contesting bodies and nation in Canadian history (pp. 53-76). University of Toronto Press.

Ross, J. A. (2015). Joining the clubs: The business of the National Hockey League to 1945. Syracuse University Press.

Smith, A. M., et al. (2000). A psychosocial perspective of aggression in ice hockey. In A. B. Ashare (Ed.), Safety in ice hockey: Third volume (pp. 125-140). ASTM Press.

Wong, J. C.-K. (2005). Lords of the rinks: The emergence of the National Hockey League, 1875-1936. University of Toronto Press.

Sources

Alsarve, D. (2022). Historicizing Machoism in Swedish Ice Hockey. International Journal of the History of Sport, 38(16), 1688–1709. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2021.2022649.

Beneteau, J. (2022, February 3). Blackhawks’ Rocky Wirtz angrily criticizes reporters for asking about Beach scandal, later apologizes. Sportsnet. https://www.sportsnet.ca/nhl/article/blackhawks-rocky-wirtz-angrily-criticizes-reporters-asking-beach-scandal/.

Brehm, M. (2024, February 2). Gary Bettman calls Canada 2018 junior hockey team sexual assault allegations ‘abhorrent’. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/hockey/2024/02/02/hockey-canada-scandal-sexual-assault-allegation-nhl-gary-bettman/72428931007/.

Brock University. (September 20, 2022). Hockey Culture Solutions & Strategies [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kOVyC8f9UD8.

The Canadian Press. (2017, October 4). A Room with a clue: Setting up an NHL dressing room sometimes takes a lot of thought. The Canadian Press. https://nationalpost.com/sports/hockey/nhl/feng-shui-nhl-style-coaches-and-players-on-the-makeup-of-a-locker-room.

Cauguiran, C., et al. (2023, November 5). Chicago Blackhawks lawsuit: Ex-‘Black Aces’ player alleges 2010 sexual assault by former video coach. ABC7 Chicago. https://abc7chicago.com/chicago-blackhawks-lawsuit-romanucci-and-blandin-sexual-assault/14014725/.

CBC News. (2016, September 15). Graham James, convicted in junior hockey sex assaults, granted full parole. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/graham-james-sex-assault-parole-theo-fleury-sheldon-kennedy-1.3762624.

CBC News: The National. (2024, February 4). Why the sexual assault conviction rates appears lower for hockey players[Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DvyuEwbwgr4.

CBC Sports Associated Press. (2021, October 28). Chicago sexual assault scandal raises culture question for NHL. CBC Sports. https://www.cbc.ca/sports/hockey/nhl/chicago-sexual-assault-kyle-beach-1.6228126.

Côté, I. (2018). A Culture of Entitlement, Silence and Protection: The Case of the University of Ottawa’s Men’s Hockey Team. Canadian Woman Studies, Special Issue: Sexual and Gender Violence in Education: Transnational, Global and Local Perspectives, 32(1), 99-110.

Cruickshank, C. (2019, January 17). Dressing room real estate: From the worst stall to the penthouse, where you sit matters. The Athletic. https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/757321/2019/01/17/dressing-room-real-estate-from-the-worst-stall-to-the-penthouse-where-you-sit-matters/.

Fogel, C., & Quinlan, A. (2023). Sexual Assault in Canadian Sport. UBC Press,

Fowler, T. A., Moore, S. D. M., & Skuce, T. (2023). The Penalty That’s Never Called: Sexism in Men’s Hockey Culture. Sociology of Sport Journal, 40(4), 452–462. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2023-0005.

GeoSports. (2014, February 17). DON’T STEP ON THE LOGO – NHL Dressing Room Protocol [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aBTqigT35xc.

Gruneau, R. and Whitson D. (1993). Hockey Night in Canada: Sport Identities and Cultural Politics. Garamond Press.

Hockey Canada. (2024). Hockey Canada Annual Report, 2023-24. https://cdn.hockeycanada.ca/hockey-canada/Corporate/About/Downloads/2023-24-hockey-canada-annual-report-e.pdf.

Hockey Canada. (n.d.a). Mandate & Mission – Who is Hockey Canada? https://www.hockeycanada.ca/en-ca/corporate/about/mandate-mission.

Hockey Canada. (n.d.b). Answers to questions by hockey parents. https://www.hockeycanada.ca/en-ca/hockey-programs/parents/faq.

Hockey Canada. (n.d.c). Safety. https://www.hockeycanada.ca/en-ca/hockey-programs/safety.

Hockey Hall of Fame. (n.d.). HHOF: Honoured members. https://www.hhof.com/HonouredMembers/MemberDetails.html?type=Builder&mem=b194502&list=ByName

Howell, C. D. (2010). Blood, Sweat, and Cheers: Sport and the Making of Canada. University of Toronto Press.

Kidd, B. (2022). The Long Struggle for Safe Sport in Canada. In J. Stevens (Ed.), Safe Sport: Critical issues and practices. Ecampus Ontario. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/safesport/chapter/the-long-struggle-for-sport-in-canada/.

Kurtzberg, B. (2012, December 20). The 25 Best Traditions in Hockey. Bleacher Report. https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1448849-the-25-best-traditions-in-hockey#:~:text=The%20Starting%20Goalie%20Leads%20the%20Team%20onto%20the%20Ice&text=That’s%20because%20he%20is%20the,as%20it%20heads%20into%20battle.

Leblanc, R. G. (2021). Uncovering the Conspiracy of Silence of Gay Hockey Players in the NHL. In Overcoming the Neutral Zone Trap (pp. 179–210). University of Alberta Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781772125894-011.

Lunney, D. (2012, February 2). Lunney: ‘Cage raging’ harmless fun? The Winnipeg Sun. https://winnipegsun.com/2012/02/02/lunney-cage-raging-harmless-fun.

MacDonald, C. A. (2014). Masculinity and Sport Revisted: A Review of Literature on Hegemonic Masculinity and Men’s Ice Hockey in Canada. Canadian Graduate Journal of Sociology and Criminology, 3(1), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.15353/cgjsc.v3i1.3764.

MacDonald, C., & Lafrance, M. E. (2018). “Girls Love Me, Guys Wanna Be Me”: Representations of Men, Masculinity, and Junior Ice Hockey in Gongshow Magazine. The International Journal of Sport and Society, 10(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.18848/2152-7857/CGP/v10i01/1-19.

McKinley, M. (2000). Putting a Roof on Winter: Hockey’s Rise from Sport to Spectacle. Greystone.

Messing, J. (2023, October 3). How Much Does It Cost To Play Ice Hockey? FloHockey. https://www.flohockey.tv/articles/11281150-how-much-does-it-cost-to-play-ice-hockey.

North American hockey leagues launch unprecedented initiative to foster safe, healthy environment. (2023, October 11). The Guelf Storm, Canadian Hockey League. https://chl.ca/ohl-storm/article/north-american-hockey-leagues-launch-unprecedented-initiative-to-foster-safe-healthy-environment/.

Staff, T. A. (2021, November 3). Hockey Hall of Fame crosses out Brad Aldrich’s name from Stanley Cup. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/4075660/2021/11/03/hockey-hall-of-fame-crosses-out-brad-aldrichs-name-from-stanley-cup/

Ordway, C. (Ed.). (2021). Restoring trust in sport: corruption cases and solutions. Routledge.

Robinson, L. (2015, June 3). Hockey’s Rape Culture. CanadaLand. https://www.canadaland.com/hockeys-rape-culture/.

Schar, RJ. (2021). Report to the Chicago Blackhawks Hockey Team regarding the organization’s response to allegations of sexual misconduct by a former coach. Jenner & Block LLP.

Sportsnet Associated Press. (2022, February 3). Brad Aldrich’s hometown still reeling from sexual assault scandal. Sportsnet. https://www.sportsnet.ca/nhl/article/brad-aldrichs-hometown-still-reeling-sexual-assault-scandal/.

Takagi, A. (2024, May 14). Hockey Canada scandal and allegations against the 2018 world junior men’s hockey team: Here’s what’s happened so far. The Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/sports/hockey/hockey-canada-scandal-and-allegations-against-the-2018-world-junior-men-s-hockey-team-here/article_61a55141-699f-5d87-8396-da1672f6165e.html#:~:text=Hockey%20Canada%20also%20revealed%20in,light%20by%20TSN’s%20Rick%20Westhead.

Touchpoint Media. (2016, January 26). The Unwritten Rules of Hockey: Part II. Sports Engine. https://www.minnesotahockey.org/news_article/show/603670-the-unwritten-rules-of-hockey-part-ii.

TSN. (2021, October 26). Chicago Blackhawks allegations – Follow the Timeline. TSN. https://www.tsn.ca/chicago-blackhawks-brad-aldrich-timeline-1.1711913.

Urbani, I. (2023, March 3). Toxic hockey culture starts young: How a player’s skill is used as a “get out of jail” card. The Peak: SFU’s Independent Student Newspaper since 1965. https://the-peak.ca/2023/03/toxic-hockey-culture-starts-young/.

Westhead, R. (2022, May 26). Hockey Canada, CHL settle lawsuit over alleged sexual assault involving World Junior players. TSN. https://www.tsn.ca/hockey-canada-chl-settle-lawsuit-over-alleged-sexual-assault-involving-world-junior-players-1.1804861.

Westhead, R. (2022, October 4). Interim board chair defends Hockey Canada’s leadership. TSN. https://www.tsn.ca/hockey-canada-andrea-skinner-scott-smith-1.1857728.

Wong, J. (2022, July 9). Inflation, rising fees are pricing families, kids out of organized sports. CBC News.https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/inflation-fees-families-sports-1.6515524.

Zuurbier, P. (2016). Cultivating distinction through hockey as commodity. In D. Taras & C. Waddell (Eds.), How Canadians communicate V: Sports (pp. 247–266). Edmonton, AB: Athabasca Press.

- Hockey Canada, n.d.a ↵

- Hockey Canada, 2024 ↵

- Hockey Canada, n.d.b ↵

- Wong, 2022 ↵

- Messing, 2023 ↵

- Zuurbier, 2016, 252 ↵

- Westhead, 2022 ↵

- Westhead, 2022 ↵

- see Gruneau and Whitson, 1993; Howell, 2010 ↵

- Wise and Fisher, 1974, 21 ↵

- Gruneau and Whitson, 1993, 37 ↵

- Hockey Hall of Fame, “Honored Members" ↵

- Gruneau and Whitson, 1993, 56 ↵

- Gruneau and Whitson, 1993, 56 ↵

- McKinley, 2000, 57 ↵

- Marsh, 2013 ↵

- Canadian Press, 2017; GeoSports, 2014; Cruickshank, 2019; Kurtzberg, 2012; Touchpointmedia, 2016 ↵

- Lunney, 2012 ↵

- Fogel & Quinlan, 2023, 50; Côté, 2018; Messner, 2002 ↵

- CBC Sports Associated Press, 2021; Cauguiran, et al., 2023 ↵

- Schar, 2021 ↵

- Sportsnet Associated Press, 2022 ↵

- The Athletic, 2021 ↵

- Beneteau, 2022 ↵

- Marsh, 2013 ↵

- Ordway, 2021 ↵

- Kidd, 2022 ↵

- see Côté, 2018; Fowler, Moore, & Skuce, 2023; Alsarve, 2022; Leblanc, 2021; Urbani, 2023; Fogel & Quinlan, 2023; MacDonald & Lafrance, 2018; MacDonald, 2014 ↵

- Robinson, 2015 ↵

- CBC News: The National, 2024 ↵

- Fogel and Quinlan, 2023, 143 ↵

- Brehm, 2024 ↵

- Hockey Canada, n.d.c ↵

- “North American hockey leagues,” 2023 ↵