15 Relational Risk Management and the Promotion of Safe Sport

Michael Van Bussel

Kirsty Spence

Themes

Relational risk management in the safe sport environment

Ethic of care for all in coaching and administration contexts

Putting safe sport policies into practice

Learning Objectives

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

LO1 Identify key topics in the area of safe sport within the Canadian sport industry;

LO2 Recognize the three stages of the Relational Risk Management Model;

LO3 Determine the degree to which athlete-centred care is present within sport organizations; and

LO4 Distinguish the degree to which organizational policy has been integrated into practice.

Overview

Key Dates

In recent years, courts have seen an increase in cases concerning athletic coaches’ and sport administrators’ negligence due to abusive conduct. Safe sport is very relevant in light of the messages communicated by both the #MeToo Movement and the tragic developments at the national sport program level (USA Gymnastics and Alpine Canada) regarding harassment and abuse of athletes. About these cases, Appenzeller (2004) explained “the suits are diverse and the awards have skyrocketed in the past few years. No one is certain how much awards will continue to escalate”.[1]

The concept of “Relational Risk” is defined as a destructive action or communication, by an administrator or coach to an athlete, which adversely affects the athlete’s self-perception and confidence. Examples of relational risk include demeaning verbal and non-verbal communication, acts of a physically violent nature toward athletes, inappropriate sexual comments or contact, or a lack of appropriate feedback.[2] Furthermore, “Relational Risk Management” is the procedure by which administrators, coaches, and athletes identify relational risks; such a procedure both helps all parties find appropriate modes of communication and enables positive communication among parties going forward.[3]

Research which has exposed negative behaviours classified as relational risk is prevalent for participants in athletic environments.[4] Literature regarding the destructive relational risk elements within a coach-athlete relationship has focused upon issues of sexual harassment or abuse.[5] This definition of risk management focuses not only on coaches or athletic administrators but also on athletes. Relational risk management incorporates athletes into the risk management process. Creating an athlete-centred concept of care in the coach-athlete communication process is an important step toward improving any sporting environment.

“While conceptualizations of care have differed, generally speaking, there are a number of unique elements which can be interpreted as constituting the core of an ethic of care. Arguably, they are also the most relevant for creating athlete-centred care and for transforming the current values and priorities of sport.”[7]

Therefore, Kirby, Greaves, and Hankivsky (2000) included three important elements in their conceptualization of care, including: Contextual Sensitivity, Responsiveness and Trust, and Consequences of Choice.[8] These three elements were foundational in the formation of a new care-driven communication model for modern competitive sporting environments. The adoption of a relational risk management plan may provide athletic administrators and coaches with a sound approach to communication that could improve relationships with their athletes. Moreover, this improved communication could positively influence the athletes’ sense of safety and improve their performance on the field.

Athlete-Centred Model

In high-performance sport, the athlete-coach relationship is dependent upon trust, reciprocal belief, and long hours of interaction. As Kirby et al. (2000) stated, “the relationship between coach and player is inherently unbalanced, and the potential for an abuse of power or authority is great”.[9] Problems occur when the coach manipulates this relationship for their own benefit. “Occasionally, coaches abuse their power and use sport to better themselves or to meet their own needs ahead of their athletes”.[10] Examples of coaches’ abuse of power range from verbal abuse to sexual harassment and physical abuse of athletes. A way to address the abuse of power exhibited by coaches is to create and enforce policy such as the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS). While valuable, we cannot rest with policies alone:

“While it is imperative to have rules, protocols and ethics of conduct to guide coach-athlete relations, there are limitations to what we can expect of such measures. By themselves, they may not be adequate for making the kinds of substantive changes to coach-athlete relationships or to the values of the sporting world that would ensure security of athletes.”[11]

The definition of athlete-centred sport is “one in which the values, programs, politics, resource allocation and priorities of the organizations and agencies emphasize consideration of athletes’ needs in a holistic sense, with performance goals set within a context”.[12] This change in philosophy, from an authoritative coach-driven model, incorporates athlete participation in the risk management process. Moreover, according to Kirby et al. (2000) “in the vision of athlete-centred sport, the potential for the abuse of power is greatly reduced”.[13] For athletes then, they must be involved in “developing codes of conduct, formulating policies regarding discipline, harassment and health and safety … Most importantly, they are more in control of what happens to them in a sport environment, and they fully expect their sport experiences to be positive, [and] to reach their potential”.[14] From the coach’s responsibility perspective, they are:

“…now held responsible for the well-being of those athletes with whom they are entrusted. This includes understanding how to undertake the role of a coach in a sensitive and ethical manner. In sum, the kind of relationship that should emerge involves a two-way rather than a one-way form of communication.”[15]

This relationship style is much more aligned with the ethic of care outlined by both Carol Gilligan (1982)[16], Nell Noddings (1984)[17], and Joan Tronto (1993). In the athlete-centred model, coaches are given the responsibility to empower their athletes and to provide a positive sport experience. Carol Gilligan’s work in her book entitled “In a Different Voice” was essential in first establishing the concept ethic of care, upon which Nell Noddings (1984) and Joan Tronto (1993) have helped to build. Tronto (1993) defined ethic of care as “a species activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue to repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible”.[18] Kirby et al. (2000) suggested that sport managers and coaches could use an ethic of care to “help guide coach-athlete relations and, more importantly, inform the transformation of the general sporting culture in which such relations operate”.[19]

From a legal perspective, does the ethic of care move beyond what would be considered a legal standard of care of a coach to his athletes? Correspondence from the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES) “interprets the ethic of care to mean that those in the business of sport have obligations beyond those of an employer for the care of sports participants. An ethic of care can therefore be seen to transcend the legal standard of care”.[20] Utilization of ethic of care as a framework for providing a safe and productive environment for athletes, coaches, and administrators is a proactive step for all parties to promote safe sport. It provides understanding to all parties in the coach/athlete relationship through contextual sensitivity, a plan of action for communication through responsiveness and trust, and responsibility for the actions of those in power positions through consequence of choice. As Kirby et al. (2000) stated:

“What makes an ethic of care unique is that it begins with an assumption of human connectedness. It prioritizes the maintenance of relationships and responsibilities (whether these are relationships between equals or those who are not equal). Instead of being formal and abstract, an ethic of care emphasizes the need for a contextual approach to moral decision-making.”[21]

Athlete-centred care can be divided into three distinct characteristics, including contextual sensitivity, responsiveness and trust, and consequence of choice. These three elements can be easily connected to the coach-athlete relationship.

Contextual sensitivity. It is important to understand for coaches to understand their players and as such, it is important for coaches to take time to listen to their athletes. This active listening may provide insight into the unique needs of these individuals. Contextual sensitivity highlights the need for understanding athletes and their diverse backgrounds. Gathering this information is important to make the best decisions for individuals and the team. As Kirby et al. (2000) stated:

“Attention to context means taking into account and thoroughly analyzing the particular political, economic and social details of people’s lives; it requires focusing on the whole person in any decision-making process. These concrete and descriptive details are integral to understanding the unique relational and situational contexts of others’ lives.”[22]

Coaches may find that building contextual sensitivity can act as a starting point for coaches and athletes from which to build their relationship.

Responsiveness and trust. Active listening is an important component of developing responsiveness and trust; “responsiveness also requires individuals to recognize when they have special obligations and responsibilities to others.”[23] The ability to be empathetic to those who may be vulnerable is an essential part of this responsibility. As Kirby et al. (2000) highlighted:

“In practice, responsiveness can protect and promote the dignity of athletes. Athletes may feel empowered to effect change in sport. And because coaches and others in positions of power are required to recognize and respond to the self-identified needs and concerns of athletes, responsiveness may also lead to more trust and respect within the coach-athlete relationship.”[24]

In turn, through responsiveness and trust, coaches are encouraged to expend attentiveness toward athletes’ needs and feelings, which in turn promotes an athlete-centred environment.

Consequences of choice. The ethic of care provides the coach with a roadmap of positive choices regarding the athlete relationship. As Kirby et al. (2000) related:

“Perhaps the most important aspect of this third principle is the attention it places on promoting well-being and preventing harm and suffering of others. Indifference and lack of concern are replaced by caring responsibility. For example, it raises awareness of how self-esteem, self-confidence and self-respect can be nurtured or alternatively destroyed in relationships of trust such as those between coaches and athletes.”[25]

In the end, the ability to reflect on the consequences of choice may result in much better decision making, as the weighing of the costs vs. benefits of positive and negative choices is analysed in light of the impact on individuals and the entire sporting community. Therefore, it can be argued that “rules and regulations which are framed within the context of an ethic of care can be truly transformative, creating a safe environment for athletes.”[26]

Case Study:

Case Study:

Centre for Sport Capacity

The long-term negative ramifications of physical, psychological and sexual abuse of athletes in sport at all levels is a significant issue that mitigates need for discussion, discourse, and action. The Centre for Sport Capacity (CSC) at Brock University has done a wonderful job promoting this discussion through a forum series.

The Centre for Sport Capacity’s 2021 Forum, called Athletes First: The Promotion of Safe Sport in Canada, was held from June 16-18, 2021 and adopted an athlete-centred focus, where topics such as governance and policy development, coaching education, athlete advocacy, and legal ramifications of harassment and abuse in sport were discussed. The audience for the Forum included athletes, coaches, sports administrators, and academics.

The CSC’s engagement in the topic of safe sport did not stop with the forum, given an additional knowledge mobilization outcome was the development of a Safe Sport Portal. The Safe Sport Portal hosts resources including videos from the forum, additional videos on the topic of Safe Sport, reference guides, important safe sport policy exemplars, materials for community sport groups and analyses of important legal cases. The objective of the Safe Sport Portal is to provide multiple stakeholders with open access to a variety of resources all may use to promote Safe Sport in their organizations.

Relational Risk Management Communication Model (RRMCM)

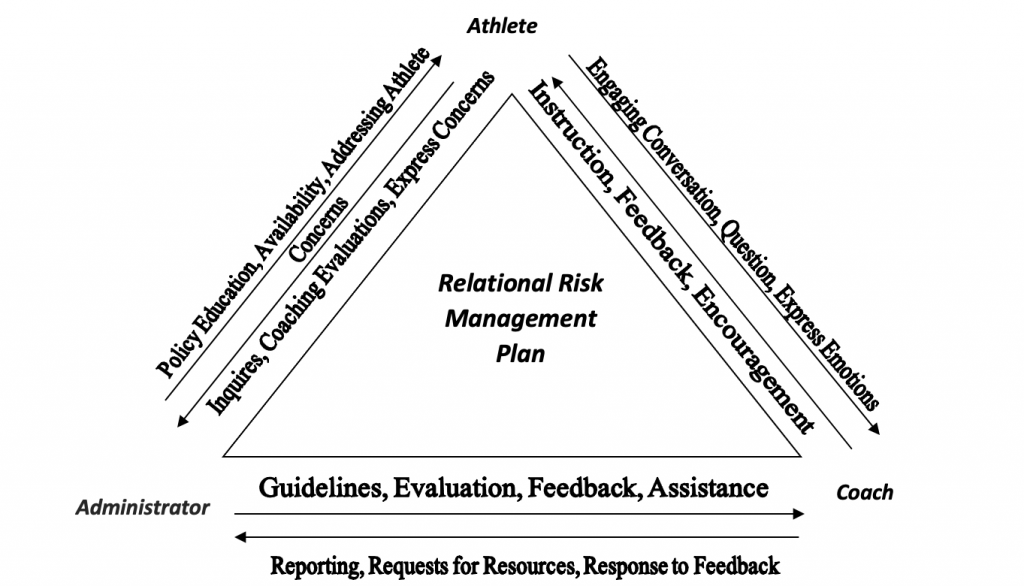

At the heart of the Relational Risk Management Model is the Relational Risk Management Policy, whether it be the UCCMS or another internal policy (see Figure 15.1).[27] Here, three parties are involved, including the athlete, the coach, and the administrator.[28] Connecting these three parties are vectors of communication responsibility, where each individual has a responsibility to communicate to the other two parties. The goal of this model is to enhance the degree of safety, enjoyment, and ultimately the performance of the athlete. This is not a hierarchical relationship; rather, the association between the athlete, the coach, and the administrator is triangular in nature.

Figure 15.1 Relational Risk Management Plan

In the RRMCM, the athlete’s responsibility to the coach is to engage in conversation, to ask questions, inquire about their role and performance, and express emotions. The athlete’s responsibility to the administrator is to ask questions, complete evaluations, and express concerns. The coach’s responsibility to the athlete is to promote instruction and error correction through honest and direct statements, give feedback on their performance, and promote an encouraging environment through use of positive feedback. The coach’s responsibility to athletic administration is to report upon athletes’ progress and performance, request needed resources, and respond to feedback from administration (i.e., respond to coaching evaluation feedback).

The administrator’s responsibility to the athlete is policy education, being available for athletes (whether via open-door policy or attendance at practices and games, or both), and addressing athlete concerns in a timely and sensitive fashion. The administrator vector of responsibility to the coach is to inform him/her of guidelines for the operation of the team and interaction with the players, complete an evaluation of the coach, provide feedback on his/her performance, and aid the coach from a resource perspective and a communication strategy perspective.

In Practice:

In Practice:

Relational Risk Management Model

An examination of administrator, coach, and athlete responses revealed that positive and negative coaching characteristics, the impact of coaching feedback, and the consideration of athletes’ emotions all had a substantial impact on athletes’ experience in their sport. Ultimately, participants’ recommendations were used in the formation of a Relational Risk Management Model.

Relational Risk Management is the process by which administrators, coaches, and female athletes identify relational risks, determine appropriate modes of communication, and ensure productive action. The adoption of a Relational Risk Management Model may provide athletic administrators and coaches with a sound approach to communication that could improve relationships with athletes. Moreover, such improved communication could positively influence athletes’ sense of safety and enjoyment and ultimately improve performance on the field.

It may be thought that the Relational Risk Management Communication Model deviates from other athlete-centred models, as it divides responsibility for communication among the athlete, coach, and administrator. It might be better to understand the RRMCM differently however, in that it incorporates the athlete into a process that, in the past, has been exclusively for the coach and the administrator. In this way, the RRMCM highlights the vectors of communication and base line expectations for each individual in the relationship. The purpose of this model is threefold: first, it is to protect the athletes involved in high-performance competition, second, it is to provide a good athletic experience, and third, it is to protect administrators and coaches from liability.[29]

The flow of communication can be both direct and indirect. For example, an athlete could express direct communication to a coach. As an example of indirect communication, if there are concerns, the flow of communication could be from the athlete to the athletic administrator and then to the coach. The feedback from coaching evaluations may work in exactly the same way. The interconnectedness of the three parties, however, provides a feedback loop to achieve the outcomes of safety, enjoyment, and positive performance within the group and on the field.

To summarize, this chapter incorporates three distinct elements to promote safe sport in Canada. First, athlete-centred care provides a clear philosophy for coaches and administrators to build an approach. Second, contextual sensitivity, responsiveness and trust, and consequences of choice provides a way to promote athlete-centred care. And finally, the Relational Risk Management Communication Model levels the playing field when involving athletes in the risk management process.

Self-Reflection

- In your preparation for a new season, how do you as a coach try to establish contextual sensitivity of the athletes you will be coaching? What information can you gather to establish such context sensitivity?

- Trust is an important part of sport. What are some things you can do to establish trust within your team and with individual athletes?

- Reflective practice is a powerful tool for coaches to use to improve both their coaching effectiveness and team performance. List three (3) tools you could adopt to promote your reflective practice as a coach and describe how you would use these tools.

Further Research

The Relational Risk Management Model and the recommendations for a Relational Risk Management Plan will provide scholars and practitioners with a starting point for developing strong and successful working relationships. Eventually, the adoption of these plans will provide a safe and enjoyable environment for both athletes and coaches, while promoting a proactive environment for sport organizational administrators.

Key Terms

Suggested Assignments

- Organizational Analysis: Examine a sport organization of your choosing. Does it utilize the UCCMS? Does it address a Safe Sport element within its organizational policy and/or organizational values? Provide an analysis of the three elements of the Relational Risk Management Model in relationship to policy examples you have found.

- Compare and Contrast: Select a Canadian national sport organization (NSO). Look for a Safe Sport policy and organizational support for Safe Sport in this organization. Provide a summary of what you have found. Next, choose a locally based same-sport organization (i.e., the same sport as the NSO). Look for Safe Sport policy and organizational support for Safe Sport in this organization. Has the message about Safe Sport filtered down from the NSO and been supported by the local sport organization? How do you know? Provide an organizational comparison.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 15.1 This figure demonstrates the relational risk management plan, shaped in a triangle with athlete, coach and administrator at its three points. From the athlete to the coach are engaging conversation, question, and express emotions, and from the coach back to the athlete are instruction, feedback, and encouragement. From the coach to the administrator are reporting, requests for resources, and response to feedback. From the administrator back to the coach are guidelines, evaluation, feedback and assistance. From the administrator to the athlete policy education, availability, and addressing athlete concerns. From the athlete back to the administrator are inquires, coaching evaluations, and express concerns. [return to text]

Sources

Appenzeller, H. (Ed.). (2004). Risk management in sport: Issues and strategies (2nd ed.). Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Clarke, H. (1995). Athlete centred sport—An athlete’s point of view. Coaches Report, 2(2), 26.

Fasting, K., & Brackenridge, C. (2009). Coaches, sexual harassment and education. Sport, Education and Society, 14(1), 21–35.

Fasting, K., Brackenridge, C., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2003). Experiences of sexual harassment and abuse among Norwegian elite female athletes and non-athletes. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 74(1), 84–97.

Frey, M., Czech, D. R., Kent, R. G., & Johnson, M. (2006). An exploration of female athletes’ experiences and perceptions of male and female coaches. The Sport Journal, 9(4), 1–5.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kirby, S., Greaves, L., & Hankivsky, O. (2000). The dome of silence: Sexual harassment and abuse in sport. Halifax: Fernwood.

Lyle, J. (2019). What is ethical coaching? International Journal of Coaching Science, 13(1), 3–17.

McNamee, M. J. (1998). Celebrating trust: Virtues and rules in the ethical conduct of sports coaches. In M. J. McNamee & J. Parry, (Eds.), Ethics and sport (pp. 148– 168). London: E & FN Spon.

Oglesby, C. A., & Sabo, D. (1996). Sexual harassment. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 67,(3), 4–6.

Ogilvie, B. C. (1993). Transference phenomena in coaching & teaching. In S. Sarpa, J. Alves, V. Ferreria, & A. Paula-Brito (Eds.), Proceedings: VIII World Congress of Sport Psychology (pp.262–266). Lisbon, June 22–27.

Pfister, G. (2010). Women in sport: Gender relations and future perspectives. Sport in Society, 13, 234–248.

Ryan, J. (1995). Little girls in pretty boxes.New York: Doubleday.

Tannen, D. (1994). Gender and Discourse. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tronto, J. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. New York: Routledge Press.

- Appenzeller, 2004, p.6 ↵

- Van Bussel, 2022 ↵

- Van Bussel, 2022 ↵

- Ogilvie, 1993; Ryan 1995 ↵

- e.g., Fasting & Brackenridge, 2009; Fasting et al., 2003; Kirby et al., 2000; Oglesby & Sabo, 1996 ↵

- McNamee, 1998, p. 167 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 143 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 125 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 124 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 124 ↵

- Clarke, 1995, p. 26 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 127 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 136 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 137 ↵

- Gilligan, 1982 ↵

- Noddings, 1984 ↵

- Tronto, 1993, p. 103 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 125 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 141 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 143 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 143 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 144 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 145 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 146 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 147 ↵

- Van Bussel, 2022 ↵

- Van Bussel, 2022 ↵

- Van Bussel, 2022 ↵