10 Dispute Resolution: Procedural and Substantive Issues

Hilary Findlay

Marcus Mazzucco

Themes

Sports law

Dispute resolution in sport

Sport arbitration

Learning Objectives

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

L01 Identify the typical parties to an arbitration hearing in the sport maltreatment context;

L02 Identify the scope of review options for an arbitrator;

L03 Describe a burden of proof and provide two examples of standards of proof;

L04 Explain the connection between the confidentiality of an arbitration process and the right to a fair hearing;

L05 Identify two different approaches that can be used by an arbitrator to interpret a code of conduct; and

L06 Explain the principle of proportionality in relation to disciplinary sanctions.

Overview

This chapter will examine the use of arbitration to resolve disputes arising from investigations into alleged violations of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport. Key issues related to the procedural and substantive aspects of arbitration will be considered, including the rights of parties to request arbitration, the scope of an arbitrator’s authority, the confidentiality of arbitration proceedings, and the principles of law used by arbitrators to interpret codes of conduct and determine appropriate sanctions for violations. Existing sport arbitration institutions, including the Court of Arbitration for Sport and the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada, will be used as examples to discuss these issues.

Key Dates

As discussed in Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution-Institutional Issues) once an investigation has concluded and a decision has been made about a violation of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS), a dispute about that post-investigation decision may arise and will be resolved by arbitration.

Arbitration is commonly used to resolve disputes in sport as is evident by the creation of sport-specific arbitration institutions at the international and national levels, such as the international Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) and the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC). Please refer to Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution-Institutional Issues) for a short backgrounder on CAS and SDRCC. In the maltreatment in sport context, arbitration is used to resolve disputes arising from investigations, as seen in the United States (U.S.) with the Judicial Arbitration Management Service (JAMS),[1] in the United Kingdom (U.K.) with the Sport Resolutions’ National Safeguarding Panel (NSP),[2] and in Canada with the SDRCC’s Safeguarding Tribunal.[3]

Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution-Institutional Issues) examined the key institutional issues associated with arbitration. This chapter explores the following six issues related to the procedural and substantive aspects of arbitration in the sport maltreatment context:

- The rights of persons to request arbitration;

- The scope of review options for an arbitration proceeding and their procedural implications;

- Establishing burdens and standards of proof to ensure a fair and just arbitration process;

- The confidentiality of the arbitration process based on the right to a fair hearing and privacy considerations;

- The principles of law that could be used by arbitrators to interpret the UCCMS; and

- The principle of proportionality and sanctions under the UCCMS.

1. Rights to Request Arbitration

As mentioned in Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution-Institutional Issues) the nature of a dispute involving a post-investigation decision and the parties involved will depend on various factors, including who conducted the investigation, who made the decision, and the substance of the decision itself. Consider the examples in Figure 10.1 below.

Figure 10.1 Dispute Scenarios for Post-Investigation Decisions

A key issue is determining who will have rights to challenge a post-investigation decision by arbitration. Some insight into this issue can be obtained from international comparators and the SDRCC’s Safeguarding Tribunal. In the U.S., for example, investigations conducted by the U.S. Center for SafeSport may result in a formal decision issued by the Center,[4] and only the respondent may request an arbitration hearing to challenge the decision.[5] In contrast, in the U.K., a national governing body[6] or any person who is subject to the rules and regulations of a national governing body and is affected by a decision made by the national governing body (or a decision-maker authorized by the body) may challenge a post-investigation decision relating to maltreatment.[7] This latter type of person could include the respondent or the complainant.

Finally, the SDRCC Safeguarding Tribunal allows the following persons to request an arbitration hearing to challenge a post-investigation decision: the respondent, the complainant,[8] the relevant sport organization, or a person who is pursuing the violation, if not the sport organization itself (e.g. an independent third party).[9] However, unlike the other parties, a complainant is only permitted to challenge a finding on a code of conduct violation, and is not permitted to challenge a proposed sanction issued under the code of conduct.[10]

In all three of the above examples, a respondent has a right to request an arbitration hearing if they want to challenge a finding that a code of conduct violation has occurred or challenge the severity of a sanction. This is not controversial as the respondent should have such rights as it is their reputation and participation in sport that is at risk. However, with respect to the rights of a complainant or sport organization to request an arbitration hearing, the U.S. SafeSport model is arguably inadequate.

A complainant whose complaint or report is investigated should have an opportunity to request a hearing if they believe that a finding on a violation of a code of conduct is wrong, or a sanction issued under that code of conduct is not severe enough. This is especially important where the complainant believes that the investigation into the code of conduct violation was flawed on procedural fairness grounds (see Chapter 8 (Investigations) for a discussion on procedural fairness protections for an investigation). Similarly, the relevant sport organization ought to have similar appeal rights as they may be familiar with the alleged maltreatment and will be impacted by a sanction that prevents a respondent from participating in the organization’s operations or activities.

Interestingly, the rules for the SDRCC’s Safeguarding Tribunal permit a sport organization to challenge a proposed sanction under a code of conduct but do not grant the same right to a complainant. Instead, the rules permit the complainant to attend the hearing as an observer and require an arbitrator to allow the complainant to submit a written impact statement and read it aloud at the hearing.[11] As discussed later on in this chapter, the sanctions issued under the UCCMS are intended to be proportionate and reasonable relative to the maltreatment that has occurred.

As a result, it is arguable that a complainant who is the subject of maltreatment should have the right to request an arbitration hearing to challenge a sanction imposed under the UCCMS. Otherwise, there may be circumstances where the rights of the complainant to participate in a hearing as an observer or presenter of a written impact statement cannot be exercised where no other party (respondent, sport organization, NIM) requests a hearing. The U.K. model seems to strike the right balance by providing a right to request a hearing to any person who is subject to the rules and regulations of a sport organization and is affected by a post-investigation decision made by or on behalf of the organization.[12]

A final consideration involves the ability of the NIM to request an arbitration hearing where an investigation is conducted by an independent third party and a post-investigation decision is made by the relevant sport organization. The NIM may wish to challenge the decision as the independent body responsible for the implementation of the UCCMS. The NIM’s right to challenge the decision would be similar to the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)’s authority to challenge anti-doping decisions made by national or international anti-doping organizations. Alternatively, the NIM could have a more passive role as an “observer” in the proceeding, which is also a right of WADA and international sport federations in the case of doping disputes heard by the SDRCC.[13]

This supervisory role of the NIM was noted by the McLaren Global Solutions Group (2020), which envisioned a similar role where a complaint falls outside the mandatory investigative jurisdiction of the NIM, and leads to an investigation by an independent third party that is overseen by a NIM investigator. A supervisory role would also address concerns raised by the sport sector about relying on the sport organization to review an independent third party’s investigative findings and determine an appropriate sanction.[14]

2. Scope of Review and its Procedural Implications

Scope of Review Options

The term “scope of review” relates to the breadth of an arbitrator’s authority to resolve a dispute involving a decision made by another decision-maker (the “original decision”). For the purposes of this chapter, the original decision would be a decision made by the NIM, the relevant sport organization or an adjudicator retained by the relevant sport organization, following an investigation into a violation of the UCCMS.

A narrow scope of review involves the arbitrator reviewing the original decision on specific grounds or for specific errors, such as an error made in interpreting or applying the applicable code of conduct or the use of an unfair procedure (see Chapter 8 Investigations) for procedural fairness considerations for an investigation and post-investigation decision).

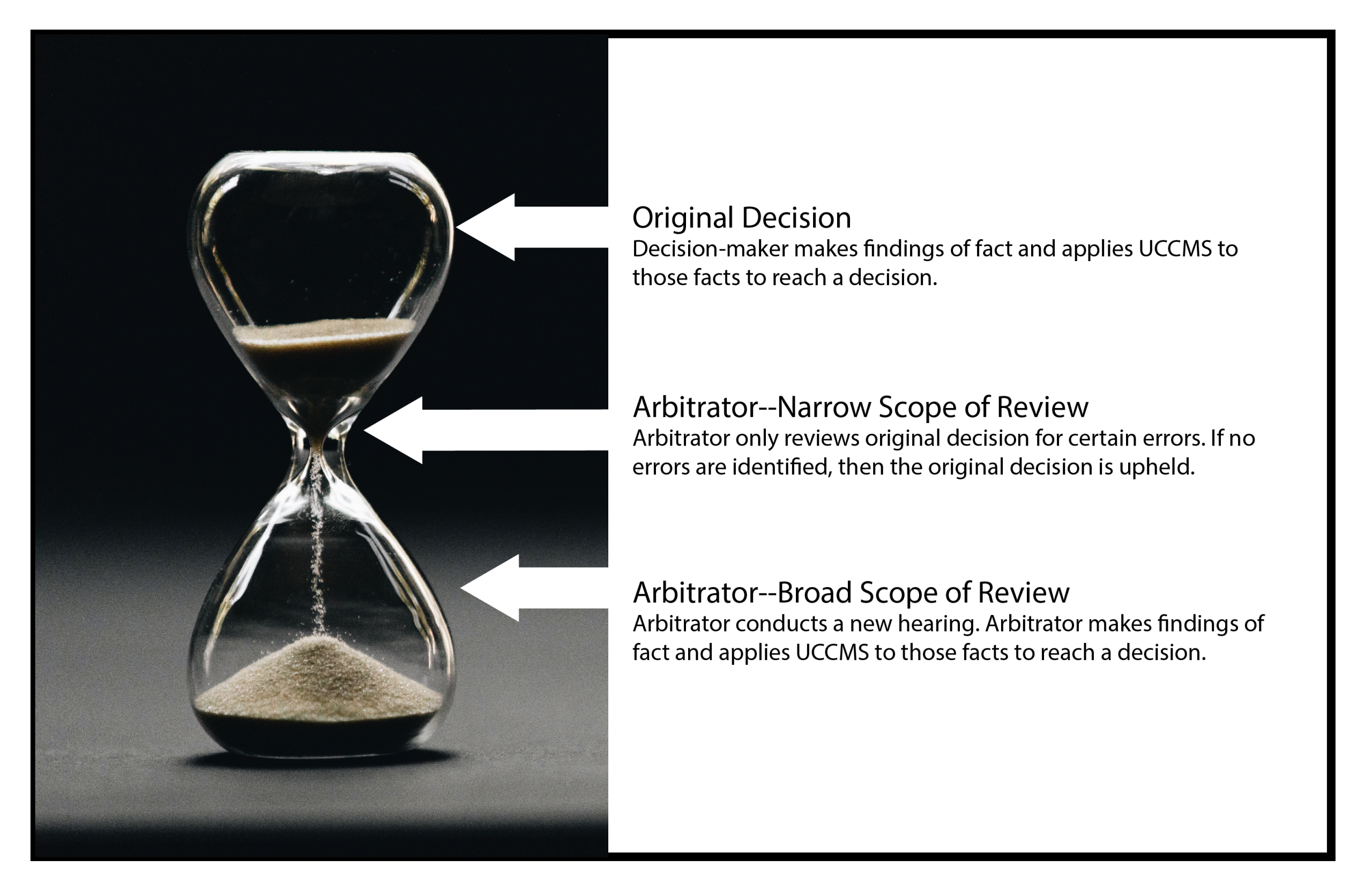

A broad scope of review involves the arbitrator conducting a whole new hearing of a matter without considering the original decision (known as a de novo hearing – which is Latin for “from the new”). In a de novo hearing, the arbitrator makes their own findings of fact based on admissible evidence (e.g. witness testimony or documentary evidence) and applies the relevant code of conduct to those facts to resolve the dispute as if the arbitrator was the original decision-maker. Figure 10.2 below depicts the scope of review options for an arbitrator in relation to the original decision as an hourglass.

Figure 10.2 Scope of Review Options

In Practice:

In Practice:

Step into the Shoes of an Arbitrator

The above section has discussed the role of arbitrators in making findings of fact in a de novo hearing. In making a finding of fact, an arbitrator answers a question of whether an alleged fact occurred (a question of fact). In contrast, arbitrators can also make conclusions of law that answer questions about the interpretation of a law or a legal principle (a question of law). Finally, arbitrators can make findings that answer questions that have factual and legal aspects (questions of mixed fact and law). Examples of a question of mixed fact and law could include interpreting a law and applying it to a set of facts or interpreting a contract.

Interpreting a contract is considered a question of mixed fact and law because the adjudicator is determining what the parties agreed upon (a factual question) based on the wording of the contract (a legal question).

To better understand an arbitrator’s role, complete the following activity by categorizing the following questions relating to the UCCMS as questions of fact, questions of law, or questions of mixed fact and law.

- What is the age of majority under Ontario laws?

- What does “psychological maltreatment” mean in the UCCMS?

- Did the respondent yell at the complainant?

- Did the respondent’s conduct constitute physical maltreatment under the UCCMS?

- What are the sport organization’s internal procedures for reporting inappropriate conduct?

- Did the organization report their concerns about the coach to the organization’s board of directors?

- Is there a duty to report under child protection legislation?

- Did the respondent fail to report the coach’s inappropriate conduct in accordance with the organization’s internal procedures in violation of the UCCMS?

- Did the respondent violate the UCCMS by directly or indirectly interfering with a UCCMS process?

- How is consent defined in Canada’s Criminal Code?

- Did the respondent tell the complainant not to report the incident?

- What does “attempting to discourage an individual’s proper participation in or use of the UCCMS’s processes” mean?

The scope of an arbitrator’s authority is agreed to by the parties. The parties’ agreement is documented in an arbitration agreement, the procedural rules of the arbitration institution (with which the parties agree to comply when they submit their dispute to the institution for resolution), or the applicable rules of the relevant sport organization (with which the parties agree to comply as a condition of participating in the sport), or a combination of these documents. For example, for appeals of selection, funding and eligibility decisions made by sport organizations, the SDRCC Ordinary Tribunal has the authority to conduct a de novo hearing, and must do so in certain circumstances, including where the process used by the previous decision-maker was procedurally unfair.[15]

However, where the SDRCC Ordinary Tribunal’s authority to conduct a de novo hearing is discretionary under the SDRCC’s procedural rules, its authority may be narrowed by the rules of the relevant sport organization that only permits an appeal to SDRCC on certain grounds.[16] In addition, where the option for a de novo hearing is discretionary and not restricted by the relevant sport organization’s rules, SDRCC Ordinary Tribunal arbitrators typically choose a narrower scope of review that is similar to the scope of review used by Canadian courts to review the decisions of statutory decision-makers, such as government officials or administrative tribunals (known as “judicial review”) (see the Case Study below for more information).[17]

In a scope of review that is similar to judicial review, the arbitrator will review the procedural and substantive aspects of the original decision.

The procedural aspects relate to the procedural fairness considerations discussed in Chapter 8 (Investigations) including a decision-making process that provides advanced notice to the respondent of an impending decision, an opportunity for the respondent to make representations to the decision-maker, and an unbiased decision-maker.

The substantive aspects relate to whether the original decision-maker had the power to make the decision and whether the decision was reasonable.

In the context of a sport organization, the authority of a decision-maker will be set out in the organization’s constitution, bylaws, or policies. The reasonableness of a decision focuses on the outcome of the decision and the decision-maker’s reasoning process, which must be transparent, understandable, and justified.[18] A decision will be unreasonable if it is arbitrary, illogical, based on improper considerations, or if it ignores relevant considerations.

Case Study:

Scope of Review in Canadian Sports Arbitration: An Accident of History or Justified?

For many years, it was believed that the decisions of private sport organizations could be challenged by way of judicial review in courts. However, the Supreme Court of Canada recently clarified that the decisions of private associations, such as sport organizations, are not subject to judicial review in courts (Highwood Congregation of Jehovah’s Witnesses (Judicial Committee) v. Wall, 2018).

Instead, courts will only review the decisions of a sport organization where a plaintiff has a cause of action and the subject matter of the dispute is justiciable – that is, appropriate for the court to decide. In the case of sport disputes, the most common type of cause of action is breach of contract .

For example, if a sport organization agrees to select athletes to a national team based on selection criteria set out in a policy or contract, and the organization does not follow the selection criteria, then an athlete could bring a lawsuit to challenge the decision on the basis of breach of contract.

However, if that selection policy or contract specifies that disputes about the team selection must be resolved by arbitration, then a court will decline to hear the matter on the basis that it is not justiciable. It is not justiciable because the parties have previously agreed to resolve their dispute by arbitration, and not in court.

The previous availability of judicial review to challenge the decisions of sport organizations may have been a factor in the selection of that scope of review by SDRCC arbitrators. The rationale may have been that, if the sport organization’s decision was subject to judicial review in the absence of an agreement to arbitrate, then arbitrators should treat the arbitration hearing as though it is a judicial review.

However, SDRCC arbitrators may also believe that a scope of review similar to judicial review is appropriate because sport organizations are similar to many administrative tribunals and government decision-makers whose decisions are subject to judicial review, and that the institutional role of SDRCC arbitrators to oversee the sport system is similar to a court.

Fact Finding

Several procedural considerations apply when selecting the appropriate scope of review. For example, one consideration for a de novo hearing is that it fixes any procedural unfairness associated with the original decision. This is because the arbitrator holds a new hearing and allows both parties to present their case on which facts exist and how the law applies to those facts, as opposed to making submissions on whether the original decision was right or wrong. This advantage has been noted by CAS arbitrators in the context of anti-doping appeals, which are heard by CAS on a de novo basis.[19] However, because a de novo hearing is a new hearing, it requires an arbitrator to make findings of fact as those made by the original decision-maker are not considered. An arbitrator can make findings of fact based on witness testimony, documentary evidence, and evidentiary presumptions.[20]

Having an arbitrator conduct a fact-finding process is helpful if the process used by the original decision-maker was flawed, but it can result in inefficiencies if the fact-finding process used by the original decision-maker was comprehensive and fair to both parties. In the context of the UCCMS, this risk of inefficiency may be high if an original decision is based on a lengthy investigation conducted by the NIM or an independent third party, and that investigative process needs to be repeated or supplemented in the arbitration hearing.

In contrast, in a scope of review that is similar to judicial review, there is no fact-finding process as the factual record before the original decision-maker is used by the arbitrator to review procedural and substantive aspects of the original decision, without considering any new facts that might have arisen after the original decision was made. Instead of a fact-finding inquiry, the arbitrator will review the procedural and substantive aspects of the original decision to identify errors, which raises a separate procedural issue – specifically, the applicable standard for determining whether the original decision-maker made an error (known as the “standard of review”).

Standards of Review

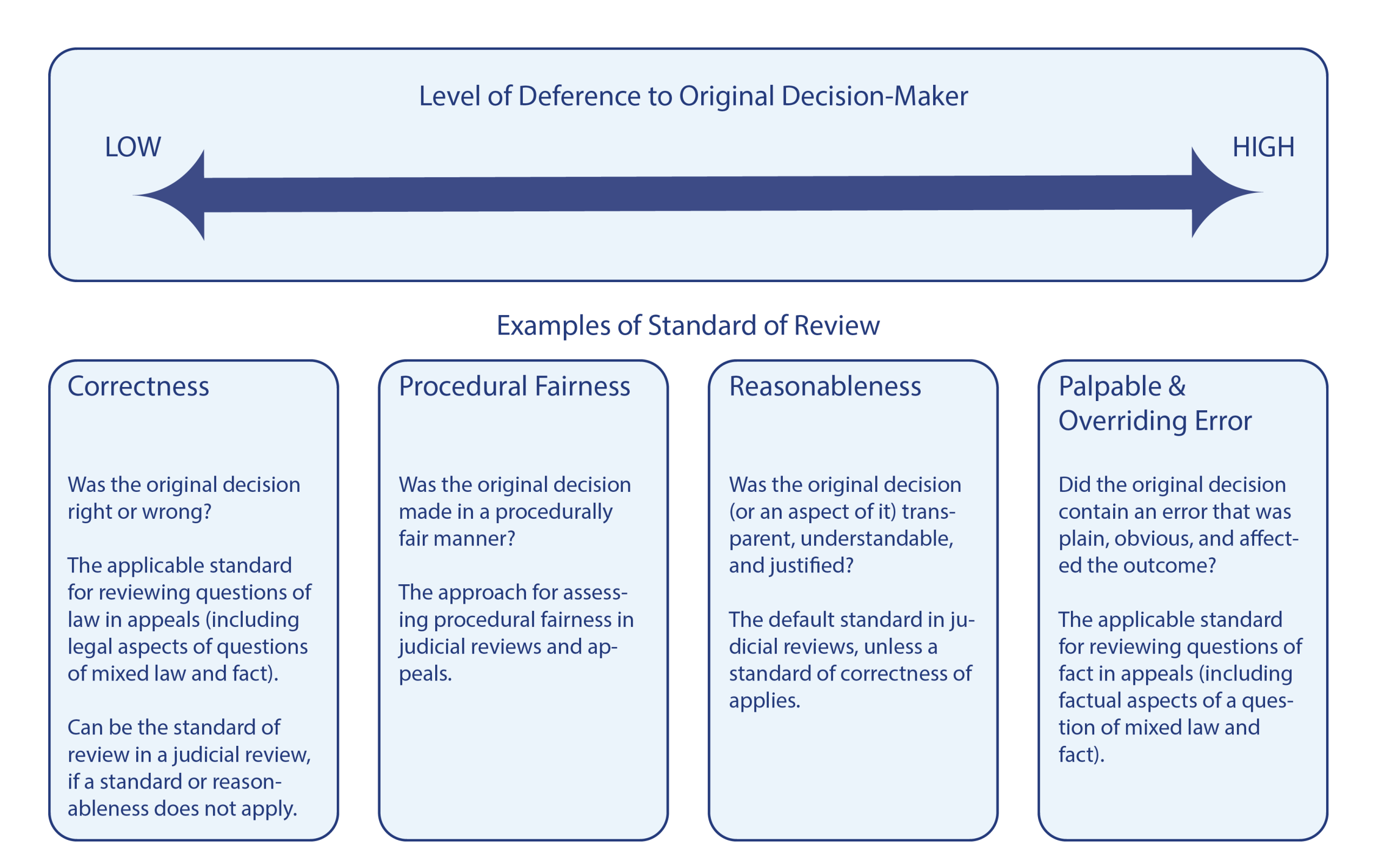

Examples of standards of review for reviewing an original decision (or an aspect thereof, such as a question of law, question of fact, or question of mixed law and fact) are correctness, reasonableness, and palpable and overriding error.

In court, the appropriate standard of review depends on whether the court is reviewing the original decision as an appeal or a judicial review. As noted above, in a judicial review context, a court will consider whether the original decision was reasonable, which involves an assessment of the outcome of the decision and the decision-maker’s reasoning process. In an appeal or judicial review context, a court’s assessment of whether an original decision was procedurally fair does not involve any of the above standards of review. Instead, the court will review what level of procedural fairness is necessary in the circumstances and whether that level has been met. Figure 10.3 below provides more information about the different standard of review used by courts in appeals and judicial reviews, including assessments of procedural fairness.

Figure 10.3 Standards of Review and Deference to Original Decision-Makers

Note 1: The following figure depicts various standards of review on a sliding scale based on the amount of deference given by the court to the original decision-maker. On the left side, the level of deference given to the original decision-maker is low, and therefore the court will scrutinize the original decision (or an aspect of it) to see whether an error was made. In contrast, on the right side of the scale, the level of deference given to the original decision-maker is high, and therefore the court will conduct a more superficial review of the decision (or an aspect of it) and only intervene if the court finds that the original decision contains a clear and obvious error.

Note 2: For each point on the sliding scale of deference (low, medium, high) is an example of the standard of review applied by courts in various settings. Procedural fairness is included near the middle because a court can defer to the choice of procedure adopted by an original decision-maker.

Shifting to the sport arbitration context, the most common standard of review used by the SDRCC Ordinary Tribunal is reasonableness due to the fact that the original decision-maker (i.e. the sport organization) has a certain level of expertise in the subject matter of the original decision and ought to be afforded deference by the arbitrator.[21] However, it is up to the party whose decision is being challenged to explain why such deference should be granted by the arbitrator when reviewing the original decision.[22] A sport organization can usually persuade an arbitrator that the appropriate standard is reasonableness in disputes involving team selection, funding and eligibility, as the sport organization has specialized knowledge in those areas.

In contrast, the procedural rules for the SDRCC Safeguarding Tribunal specify that, in the context of a challenge to a finding regarding a violation of a code of conduct, the standard of reasonableness applies to assessing whether the original decision-maker made certain errors (such as misinterpreting or misapplying the code of conduct), whether there was a breach of procedural fairness, or whether there is new evidence to consider.[23] This standard of reasonableness is arguably inappropriate for several reasons:

- First, it is unclear how this standard would apply to an assessment of whether new evidence should be considered by the arbitrator, as this assessment does not involve a review of the original decision for any error.

- Second, the standard is inconsistent with the assessment used by courts for determining the procedural fairness of an original decision. As noted above, a court will consider what level of procedural fairness is necessary in the circumstances and whether that level was met when the original decision was made.

- Third, a standard of reasonableness may provide too much deference to the original decision-maker in certain cases.

Where the original decision is made by the NIM following an investigation conducted by the NIM, a standard of reasonableness may be appropriate since NIM will presumably have expertise in interpreting and applying the UCCMS. In contrast, where the original decision is made by a sport organization or a third party adjudicator retained by the sport organization, a less deferential standard, such as correctness, may be more appropriate as the sport organization or other decision-maker may have less expertise in interpreting and applying the UCCMS, at least in the infancy of implementing the UCCMS.

Scope of Remedies

A final procedural consideration that applies when selecting the appropriate scope of review is the scope of remedies that may be granted by the arbitrator. In a de novo hearing, an arbitrator is not considering the original decision and will therefore issue a new decision that replaces the original decision. In contrast, in a narrower scope of review, an arbitrator may refer the matter back to the original decision-maker with instructions to correct any error identified by the arbitrator, if a resolution of the dispute is not urgent and the original decision-maker (i.e. the sport organization) has a particular expertise over the subject-matter underlying the dispute, such as a team selection decision involving the exercise of discretion.[24]

The procedural rules of a sport arbitration institution typically give an arbitrator a broad scope of authority to grant remedies – likely to reflect that the scope of the arbitrator’s review may vary depending on the circumstances. For example, for SDRCC’s procedural rules authorize the SDRCC Ordinary Tribunal to substitute its decision for the original decision or to grant such remedies that the Tribunal deems just and equitable in the circumstances,[25] which may include referring the matter back to the original decision-maker to re-make the decision after correcting any procedural or substantive errors identified by the arbitrator. Similarly, the SDRCC procedural rules authorize the Safeguarding Tribunal, in certain circumstances, to impose such consequences and/or risk management measures as seem fair and just, after considering the relevant sport organization’s rules.[26] (See Section 6 of this chapter “The Principle of Proportionality and Sanctions under the UCCMS” for further discussion on sanctions).

Recommended Scope of Review

What is the appropriate scope of review for disputes involving post-investigation decisions related to maltreatment in sport based on the procedural implications discussed above? To answer this question, it is helpful to look at the context in which the dispute will arise. As noted earlier, the dispute involves a decision made by the NIM or the relevant sport organization following an investigation into a violation of the UCCMS.

Chapter 8 (Investigations) discusses the elements required for a procedurally fair investigation and original decision. Assuming those elements are incorporated into the investigation and decision-making processes, it may be unnecessary to have a de novo arbitration hearing that makes new or fresh findings of fact. Repeating or supplementing a fact-finding process at the arbitration stage could re-traumatize complainants and witnesses, as well as substantially increase the time and resources required for the arbitration hearing. As a result, it may be appropriate to limit the availability of a de novo hearing to instances where the original decision was made in a procedurally unfair manner that can only be remedied by a new decision-making process conducted by the arbitrator.

Where a de novo hearing is not warranted, the arbitrator’s role could be limited to reviewing the original decision on specified grounds (e.g. an error in interpreting or applying the UCCMS or procedural unfairness). In other words, the arbitrator begins with a narrower scope of review and only expands to a de novo hearing to remedy procedural unfairness in the making of the original decision. In a narrower scope of review, consideration must be given to the appropriate standard of review .

To learn more about the different types of arbitration hearings available in the United States Safe Sport model, watch the video Hearing Process: Response and Relation.

This narrow-to-broad scope of review approach is taken by the SDRCC’s Safeguarding Tribunal and may provide insight into how the SDRCC would determine the scope of review of arbitrators that review decisions made by the NIM. However, this narrow-to-broad approach would be somewhat inconsistent with the safe sport arbitration models in the U.S. and the U.K. The U.S. model permits a de novo hearing where a respondent challenges the merits of the Center’s finding of a code violation, and a strict narrower scope of review where a respondent challenges a sanction or a finding of a code violation based on a criminal charge or disposition, such as a conviction.[27] In contrast, in the U.K. model, the NSP Safeguarding Panel’s arbitration rules are silent on the applicable scope of review, likely to allow the parties and arbitration panel to decide on the appropriate scope and related procedural matters prior to the hearing[28]

Table 10.1 below compares the scope of review and related procedures of arbitrators in the U.S. SafeSport, U.K National Safeguarding Panel, and SDRCC’s Safeguarding Tribunal models.

Table 10.1 International Comparison of Scope of Review and Procedural Rules

| Jurisdiction | Scope of Review | Related Procedures (Standard of Review, Evidence & Remedies) |

|---|---|---|

|

U.S. SafeSport Arbitration.[29] |

In the case of a merit-based hearing – de novo hearing |

No standard of review. Flexible and comprehensive rules of evidence to enable fact-finding on alleged violations of SafeSport Code. Arbitrator may grant such remedy or relief as they deem just and equitable within scope of the Code and sanctioning guidelines. |

|

In the case of a hearing concerning sanctions or violation of SafeSport Code due to criminal charges or dispositions – appeal/review on narrow ground (whether abuse of discretion occurred). |

No standard of review as arbitrator is assessing whether the Center abused its discretion, not whether the Center’s decision or an aspect of the decision involved an error. No fact-finding as violation of code and underlying facts are established and irrefutable. Arbitrator’s review is based on Center’s decision, parties written submissions, and oral submissions (if permitted by arbitrator). Arbitrator may modify sanction issued by Center if abuse of discretion is found. |

|

|

U.K. National Safeguarding Panel Arbitration.[30] |

Scope of review determined by arbitrator and parties prior to hearing |

Procedural rules silent on standard of review. (If not a de novo hearing, then, presumably, arbitrator would select standard of review based on parties’ submissions). Flexible and comprehensive rules of evidence to align with scope of review, including appointing independent experts and requiring production of documents. Arbitrator can issue sanctions or risk management measures as seem fair and just (which would replace original decision). |

|

SDRCC – Safeguarding Tribunal.[31] |

In the case of a challenge to a finding on a code violation – appeal on narrow grounds (specific errors, procedural unfairness, new evidence). |

Standard of review is reasonableness. Review based on documentation (not testimony), unless panel orders otherwise. Silent on scope of remedies. |

|

In the case of a challenge to a proposed sanction – similar to judicial review. |

SDRCC Code silent on standard of review. (presumably, arbitrator to select standard of review based on parties’ submissions). Presumably, no fact-finding if review focused on appropriateness of sanction. Arbitrator can issue sanctions or risk management measures as seem fair and just (which would replace original decision). |

|

|

If a challenge to finding on a code violation reveals bias, then arbitrator conducts a de novo hearing. |

No standard of review. Flexible and comprehensive rules of evidence to align with scope of review, including appointing independent experts and requiring production of documents. Silent on scope of remedies.

|

3. Establishing Burdens and Standards of Proof to Ensure a Fair and Just Arbitration Process

A burden of proof refers to a party’s responsibility to prove a particular fact or matter in a legal proceeding. Burdens of proof impact how a party behaves in a proceeding in terms of what arguments they make and what evidence they introduce. A party with a burden to prove a certain fact must take proactive steps to meet that burden.

In contrast, a party without a burden may decide to do nothing (as they don’t have to assist the other party in meeting the burden) or may decide to take reactive steps to rebut the arguments made or evidence introduced by the other party to prevent that other party from meeting their burden.

To use a sport analogy, a party with a burden of proof is on the offensive, while the other party is on the defensive. See Figure 10.4 below for further explanation.

Figure 10.4 Burdens of Proof as a Sporting Analogy

To determine whether a party has met their burden to prove a particular fact or matter, a threshold or standard must be applied (known as the standard of proof). To return to our sport analogy, the standard of proof would be the end zone that the offensive party must enter to score. The higher the standard, the further away the end zone is from the offensive party. There is a sliding scale of standards of proof in law. Figure 10.5 depicts the various standards of proof as different end zones on a sports field.

Figure 10.5 Standards of Proof Illustrated

Allocating Burdens of Proof

Burdens of proof can be assigned to both parties in a legal proceeding. In the sport maltreatment context, the allocation of a burden of proof will depend on an arbitrator’s scope of review (see Section 2 “Scope of Review and its Procedural Implications” above). For example, in a de novo hearing where the arbitrator is making factual findings to determine whether a violation of the UCMMS occurred, it is fair to assign the burden of proving a violation to the party pursuing the violation, which will be the NIM or the relevant sport organization whose original decision was challenged.

If a violation of the UCCMS is established, then each party would have the burden to prove why their proposed sanction should be accepted by the arbitrator by proving the existence or application of certain factors. However, if a presumptive sanction applies based on the UCCMS violation, such as a permanent ineligibility, then the respondent will have the burden to explain why that sanction is not fair and appropriate based on certain factors (see Section 6 “The Principle of Proportionality and Sanctions under the UCCMS” below for a discussion on the proportionality of sanctions).

In a narrower scope of review, there is no burden of proof to be assigned because the arbitrator is reviewing the original decision for specific errors, and not engaging in fact finding process that requires a party to prove a fact based on a certain standard. For example, if a party is challenging an original decision on specific grounds (such as an error made in interpreting or applying the UCCMS or procedural unfairness), then the focus is on the relevant standard of review (see Section 2 “Scope of Review and its Procedural Implications” above).

However, where an arbitrator concludes that an original decision is procedurally unfair or contains a substantive error, the arbitrator may assume a fact-finding role requiring the allocation of burdens of proof. For example, if an arbitrator concludes that an original decision should be overturned and replaced because the sanction imposed is unreasonable, then the arbitrator may require the parties to make submissions on appropriate sanctions that requires them to prove certain factors.

Similarly, if the arbitrator concludes that the original decision was procedurally unfair and that this should be remedied by a de novo hearing conducted by the arbitrator, then the above discussion about allocating burdens of proof in a de novo hearing applies.

To summarize, an arbitration institution’s procedural rules for allocating burden of proof will depend on an arbitrator’s scope of review and the type of hearing that flows from that scope. In the U.S., for example, because a de novo hearing is offered for merit-based challenges to an original decision made by the Center, the procedural rules for that type of hearing specify that the Center has the burden of proof. In contrast, for the SDRCC Safeguarding Tribunal, because there are different types of hearings contemplated (a de novo hearing or a narrower scope of review), the procedural rules include one general rule that the party asserting a particular fact or matter has the burden to prove it.

This latter type of procedural rule is appropriate where there is flexibility in the breadth of an arbitrator’s scope of review and type of hearing. However, it will be the responsibility of the arbitrator to clarify for the parties how the rule will be applied in the context of a de novo hearing compared to a narrow review of an original decision on specific grounds. This clarification should be provided during any preliminary meetings amongst the parties and arbitrator prior to the start of the hearing so that the parties know what to expect during the hearing.

Determining an Appropriate Standard of Proof

Once burdens of proof have been allocated between or amongst parties to an arbitration proceeding, the relevant standard(s) of proof must be determined. Figure 10.5 above provides examples of the different standards of proof that exist in law. What is the appropriate standard of proof in the sport maltreatment context?

In the U.S. and U.K. safe sport models, and in the SDRCC Safeguarding Tribunal, the relevant standard of proof is a “balance of probabilities.” As noted above, this standard is met when an arbitrator is satisfied that it is more likely that something is true than false (i.e. being 51% sure of something). This requires evidence that is clear, convincing, and persuasive.[32] A balance of probabilities is the only standard of proof used in civil lawsuits, including those involving sexual assault and battery.[33] It is also the standard used by child protection authorities in Ontario when conducting an investigation.[34]

In contrast, in the anti-doping and disciplinary contexts of sport, CAS has held that the applicable standard of proof is a “comfortable satisfaction”.[35] This standard is greater than a balance of probabilities but less that proof beyond a reasonable doubt, and it is met when an arbitrator is comfortably satisfied that it is far more likely that something is true than false. CAS has justified the standard due to the seriousness of allegations involved in doping and disciplinary disputes and their consequences.[36] Following CAS decisions, the standard of a comfortable satisfaction was incorporated into the World Anti-Doping Code. However, the standard only applies to an anti-doping organization’s burden to prove an anti-doping rule violation and, for all other burdens that might arise in a doping hearing, the applicable standard of proof is a balance of probabilities.[37]

The comfortable satisfaction standard is very similar to the standard of “clear and convincing evidence”. The clear and convincing standard is used in the discipline hearings of certain regulated professions in Canada, but only if the standard is set out in legislation (see, for example, Ontario’s Police Services Act ). In the U.S., the standard is also used in some civil proceedings involving morally blameworthy conduct, such as fraud or conduct giving rise to punitive damages.[38] It is also used in U.S. administrative proceedings where personal liberties are at stake, such as withdrawing life support[39] or child custody determinations.[40]

In the News:

Russian Doping Scandal

“The Russian Doping Scandal,” Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, Feb. 22, 2018.

“Russian Doping Scandal: Athletes Face Potential Ban from Global Sport,” BBC, Dec. 9, 2019.

“How Russian Doping Scandal Unfolded,” France24, Dec. 17, 2020.

Following investigative journalism into state-sponsored doping in Russia and a 2016 WADA investigation into the same issue, the IOC established a disciplinary commission to conduct hearings involving Russian athletes who were implicated in the WADA investigation. The IOC disciplinary commission concluded that the athletes had committed anti-doping rule violations through their participation in a state-sponsored doping scheme at the 2014 Olympic Games in Sochi and, as a consequence of those violations, disqualified the athletes’ results at the 2014 Olympic Games and banned them from competing at any future Olympic Games.

The athletes appealed the IOC disciplinary commission’s decision to CAS. CAS upheld the majority of the athletes’ appeals and overturned the IOC’s sanctions on the basis that the indirect evidence obtained from the 2016 WADA investigation did not meet the standard of proof for proving the alleged anti-doping rule violations (see, for example, Smolentseva v. IOC, 2017). This outcome was somewhat surprising as CAS had relied on indirect evidence to be comfortably satisfied of an anti-doping rule violation in previous decisions.[41]

Should the standard of proof of comfortable satisfaction or a balance of probabilities be applied to establishing a violation of the UCCMS?

The answer involves a balancing of rights and interests. From the perspective of a respondent, an alleged violation of the UCCMS is serious due to its moral blameworthiness and its potential consequences to the respondent’s reputation, livelihood, and ability to participate in sport. The seriousness of the allegations and their related consequences is comparable to that seen in doping disputes before CAS, which suggests that a standard of comfortable satisfaction may be more appropriate than a balance of probabilities.

However, it is important to keep in mind that the disputes heard by CAS involve international-level athletes and officials, and therefore the consequences of an alleged violation may be more serious than the consequences at lower levels of sport where a respondent may only be a volunteer.

Further, and perhaps more importantly, CAS may not be the most appropriate comparator for the sport maltreatment context, despite being an institution in the sport system. Domestic legal systems may be a better comparator due to their overlap with the subject matter of the sport maltreatment context. For example, a violation of the UCCMS may lead to a civil lawsuit for assault or battery where the standard of a balance of probabilities would apply.

Similarly, a violation of the UCCMS may also trigger an investigation or proceedings under provincial or territorial child protection legislation, where the balance of probabilities standard would be used. Finally, even in domestic legal proceedings outside of Canada that use a standard of clear and convincing evidence due to the liberty interests at stake (e.g. ending life support, suspending parental rights), the interests of a respondent under the UCCMS arguably do not reach the same level of importance.

From the perspective of the complainant, the NIM or other person pursuing the violation of the UCCMS, it is important to recognize the evidentiary burden associated with a standard of proof that is higher than a balance of probabilities, such as a comfortable satisfaction. The evidence available in a maltreatment case may be very different than the evidence available in a doping case, so imposing a standard higher than a balance of probabilities may be unfair to complainants and those pursuing violations. Evidence in maltreatment cases will typically involve the allegations of complainants and witnesses expressed through interviews with an investigator or testimony at an arbitration hearing.

In some cases, physical and documentary evidence may also exist to corroborate the allegations of complainants and witnesses. In the absence of such corroborating evidence, an arbitrator in a de novo hearing will assess the allegations of complainants and witnesses based on their credibility.

In contrast, the evidence in doping hearings to prove an anti-doping rule violation is usually an adverse analytical finding from an athlete’s urine sample, which will meet the comfortable satisfaction standard, provided that the specimen collection and laboratory analysis complied with applicable requirements. However, where other evidence is used in doping hearings to prove anti-doping rule violations, such as indirect evidence from an investigation into state-sponsored doping,[42] then the standard of a comfortable satisfaction may not be met (see “In the News: Russian Doping Scandal” above).

The evidentiary burden associated with a higher standard of proof also has practical implications for an arbitrator. As noted by the Supreme Court of Canada in the case of F.H. v. McDougall (2008), at para. 43:

An intermediate standard of proof presents practical problems. As expressed by Rothstein, Centa and Adams, at pp. 466-67 [in “Balancing Probabilities: The Overlooked Complexity of the Civil Standard of Proof,” in Special Lectures of the Law Society of Upper Canada 2003: The Law of Evidence]:

“[S]uggesting that the standard of proof is ‘higher’ than the ‘mere balance of probabilities’ inevitably leads one to inquire: what percentage of probability must be met? This is unhelpful because while the concept of ’51 percent probability,’ or ‘more likely than not’ can be understood by decisionmakers, the concept of 60 percent or 70 percent probability cannot.”

In other words, a standard of a comfortable satisfaction or clear and convincing evidence may be difficult to apply in practice. Although sport arbitrators may be familiar with this standard in the doping context, the type of evidence used to establish an anti-doping rule violation in doping hearings is different than the evidence used in the sport maltreatment context.

Further, where sport arbitrators have had to consider indirect or circumstantial evidence of an anti-doping rule violation, there seems to be inconsistency in how the standard is applied to such evidence (see “In the News: Russian Doping Scandal” above), which is an important consideration for the sport maltreatment context. Finally, it is worth repeating that, in the doping context, for burdens to prove something other than an anti-doping rule violation (such as an athlete’s level of fault or negligence when determining a period of ineligibility), the lower standard of a balance of probabilities applies, and the type of evidence used to satisfy those burdens is likely to be similar to the type of evidence relevant to a sport maltreatment hearing (e.g. testimonial evidence).

In summary, in the sport maltreatment context, a standard of a balance of probabilities is the most appropriate standard of proof having regard to the rights and interests at play and would be consistent with the standard of proof used in Canada where similar misconduct is alleged in civil litigation, as well as the arbitration rules used for the U.S. SafeSport model, the U.K. National Safeguarding Panel, and the SDRCC Safeguarding Tribunal.

4. Protecting Privacy Interests in the Arbitration Process

The final procedural issue discussed in this chapter concerns the confidentiality of the arbitration process. When we think about the resolution of disputes in a legal proceeding, we may picture a busy courtroom with a judge, the parties and their representatives, as well as observers who have an interest in the case, such as the media or other members of the public.

As noted in the introduction to Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution-Institutional Issues) one of the key differences between resolving disputes through litigation in courts compared to private arbitration is the publicness or openness of litigation in courts. In Canada, this openness extends to the proceeding in the courtroom, any written submissions or evidence filed by the parties in court, and the court’s decision. This principle of openness in courts is protected under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, particularly in criminal cases, and is linked to the freedom granted to the press to report on what happens in court.[43] Aspects of a court proceeding can be protected from public disclosure through publication bans and court orders that seal elements of a court file to protect privacy rights and other interests; however, such measures are an exception to the general rule of openness.

In contrast, private arbitration proceedings can be confidential and closed to the public, if the parties to the arbitration agree. This confidentiality can apply to the arbitration hearing (including the submissions and evidence filed by the parties), and the arbitrator’s decision. Like other aspects of the sport arbitration process, the parties’ agreement on the confidentiality of an arbitration proceeding can be documented in an arbitration agreement, the procedural rules of the relevant arbitration institution, or the rules of the relevant sport organization, or a combination of these documents. Table 10.2 below provides a summary of the confidentiality rules in the procedural rules of CAS and SDRCC.

Table 10.2 Summary of CAS and SDRCC Confidentiality Rules

|

CAS |

SDRCC |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Arbitration Hearing |

General rule: confidential and closed to the public, unless both parties agree otherwise.[44] Exception: in the case of disciplinary and doping hearings, one party may request a public hearing, but this request may be denied in the interests of morals, public order, national security, to protect the interests of minors or privacy interests, to avoid harm to the interests of justice, or where the hearing is exclusively related to a question of law.[45]

|

General rule: confidential and closed to the public.[46] Exception: in the case of a doping hearing, one party may request a public hearing, but this request may be denied in the interests of morals, public order, national security, to protect the interests of minors or privacy interests, to avoid harm to the interests of justice, or where the hearing is exclusively related to a question of law.[47] |

|

Arbitration Decision |

Ordinary Arbitration Division – decision is confidential, unless both parties agree otherwise.[48] Appeals Arbitration Division – decision is made public, unless both agree otherwise.[49] Anti-Doping Division – decision is published.[50] |

Ordinary Tribunal – decision is made public, unless both agree otherwise.[51] Doping Tribunal – decision is published.[52] |

The confidentiality of arbitration proceedings in the sport maltreatment context raises three main questions listed below. The following sections address these three questions in turn.

Q1 Based on the concerns discussed in Chapter 7 (Jurisdiction) relating to the forced or coerced nature of consent in sport contracts, how does that impact how consent-based confidentiality rules are viewed?

Q2 Are there any limitations on a party’s ability to consent to an open or non-confidential arbitration proceeding and how do they relate to the sport maltreatment context?

Q3 What unique confidentiality rules or exceptions may be needed for the sport maltreatment arbitration context?

Q1: How does the coerced nature of consent in the sport arbitration context impact how consent-based confidentiality rules are viewed?

The issue of consent was considered in a recent case spanning over 10 years and involving German speedskater Claudia Pechstein. At the 2009 World Championships organized by the International Skating Union (ISU), Pechstein underwent a doping control test that examined a sample of her blood. Although the test did not identify the presence of a prohibited substance, it revealed certain parameters that were deemed irregular based on a longitudinal analysis of her blood over a period of time (also known as a biologic passport). Based on this indirect evidence, the ISU’s disciplinary panel concluded that a doping violation had occurred, and suspended Pechstein from competition for two years.

Pechstein appealed the ISU’s decision to CAS. She challenged the reliability and accuracy of the doping control test and argued that any irregularity found was due to an inherited condition. Pechstein requested a public hearing, but her request was denied in accordance with the CAS procedural rules in force at the time. CAS dismissed Pechstein’s appeal and upheld the ISU’s decision. Subsequently, Pechstein appealed the CAS decision to the Swiss Federal Tribunal (SFT) and argued that the CAS arbitration panel was not independent and impartial. SFT dismissed the appeal, so Pechstein then sought relief from German courts.

Pechstein had varying degrees of success at the trial and appeal in German courts, but ultimately lost in German’s highest court – the German Federal Tribunal. Finally, Pechstein sought recourse from the European Court of Human Rights (EHCR) by alleging that CAS procedures, including those relating to confidential hearings, violated article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights (Convention), which protects the right to a fair trial.

The EHCR noted that the public nature of legal proceedings was a fundamental aspect of the right to a fair trial protected under Article 6 of the Convention. The EHCR reasoned that holding a public hearing protects parties against justice being administered in secret without public scrutiny and was necessary to ensure public confidence in courts. It also held that this right may be limited in certain circumstances, such as:

- Where a hearing does not deal with issues of witness credibility or contested facts and can resolved based on the parties’ written submissions;

- Where the adjudicator has a narrow scope of review and is only reviewing an original decision on certain questions, such as whether the original decision was procedurally unfair or was based on an error of law; and

- Where the exceptions to a public hearing in article 6 of the Convention apply, such as in the interests of morals, public order, national security, to protect the interests of minors or privacy interests, or to avoid harm to the interests of justice.

The EHCR ultimately held that Pechstein’s rights under article 6 of the Convention had been breached by CAS. It held that the question of whether Pechstein was justifiably banned for doping and the hearing of expert testimony on that issue made it necessary to a hold a hearing under public scrutiny. The EHCR highlighted that the facts were disputed and that the ban imposed on Pechstein carried a degree of stigma and was likely to adversely affect her professional honour and reputation.

However, one of the most important aspects of the EHCR’s decision was the court’s interpretation of the right to a public hearing in the context of a consent-based arbitration process. The EHCR held that article 6 does not prevent an individual from waiving, of their own free will, the right to have their case heard in public. However, where arbitration is compulsory (as was the case for Pechstein), the individual should have the choice of a public hearing, unless one of the above limitations apply. This interpretation impacts how consent is viewed in the arbitration context.

As discussed throughout this chapter and Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution-Institutional Issues) many aspects of the arbitration process (including the decision to arbitrate) depend on having the consent of both parties to the dispute. However, this consent model is problematic for two reasons. First, a sport participant’s consent to the rules of sport (including rules requiring the resolution of disputes through arbitration) is forced, and arguably illusory, because the rules are imposed unilaterally on the participant. The participant has the option to accept the rules or not participate in the sport, and for many participants, this may not be seen as a fair or free choice.

Second, even if a participant’s consent to sport rules is considered valid, the requirement for both parties to agree on the confidentiality of an arbitration proceeding means that one party can always override the other party’s wishes. This two-party consent model is incompatible with an individual’s right to a public hearing, as the individual cannot exercise the right independently and freely. As a result, in the context of the confidentiality of a public hearing, one party should have the ability to request a public hearing, and that request should not be conditional on the other party’s consent.

This reasoning should apply to the sport maltreatment arbitration context. As discussed in earlier sections, the arbitration proceeding in a sport maltreatment case may involve a de novo hearing where disputed facts and the credibility of witness are central. In addition, allegations of violations of the UCCMS are serious due to their immoral character and the potential consequences of a violation on a respondent’s reputation, livelihood, and ability to participate in sport. As a result, the right to a public hearing should be available in the sport maltreatment context, subject to the limitations discussed below.

Q2: Are there any limitations on a party’s ability to consent to an open or non-confidential arbitration proceeding? How do they relate to the sport maltreatment context?

Following the EHCR’s decision in the Pechstein case, CAS amended its procedural rules to specify that, in the case of doping and disciplinary hearings, one party may request a public hearing, and that the request should be granted, unless the limitations specified above apply (see Table 10.2 above). Although the EHCR’s decision is not binding in Canada, it also led to similar changes to the SDRCC’s procedural rules for doping hearings in 2021 (also see Table 10.2 above).

One key difference between the CAS and SDRCC rules relates to the process for denying a request to a public hearing. In the case of CAS doping and disciplinary hearings, the request for a public hearing can be denied if the arbitration panel concludes, on its own initiative, that a specified limitation applies.[53] In contrast, for SDRCC doping hearings, the other party to the proceeding must object to the public hearing in order for the arbitration panel to deny the request on one of the specified limitations.[54] This difference raises an interesting question about the role of the arbitration panel in reviewing requests for a public hearing.

Should the panel have the ability to decide, at is own initiative, that a public hearing not be granted, or should the panel’s authority only arise where the other party has objected to the request for a public hearing?

The former option requires the arbitrator to take on a proactive role, whereas the latter option requires the arbitrator to assume a more reactive role.

Which option is more appropriate?

Arguably, the CAS approach is more appropriate as it requires the arbitrator to take on a supervisory role over the proceeding, which is consistent with other typical powers of an arbitrator to control the hearing process. In addition, it avoids a potential issue with relying on a party to object to the request for a public hearing, when the rights or interests of that party do not overlap with any of the specified limitations to a public hearing. This issue also relates to our earlier discussion regarding the persons who can request an arbitration hearing (see Section 1).

If, for example, the parties to a sport maltreatment arbitration hearing are the respondent (who wants to exercise their right to a public hearing) and the NIM or relevant sport organization (whose original decision is being challenged), and a closed hearing is necessary to protect the interests of a minor who is a complainant or witness but not a party to the proceeding, then it will be up to the NIM or sport organization to raise an objection as an advocate for the minor’s interests. While the NIM or sport organization could certainly fulfill this advocacy role, it puts an obligation on them that may, in certain circumstances, conflict with their interests that might favour an open or transparent hearing. To avoid such conflicts, the arbitrator should have the discretion to reject a request for a public hearing on their own initiative.

Turning to the limitations on the right to a public hearing, it is necessary to apply the limitations to the sport maltreatment arbitration context. With respect to the interests of morals and public order, discussing specific allegations of maltreatment in a public hearing may incite violence or threats of violence towards the parties to the hearing, such as the respondent or a sport organization. For example, in the Larry Nassar trial featured in the Case Study video above, one of the parents of Nassar’s victims physically attacked Nassar in the courtroom and his lawyers (and their children) received death threats.[55]

With respect to the protections of minors and privacy interests, these limitations are particularly relevant. Allegations of maltreatment under the UCCMS are likely to involve minors, as well as sensitive personal information about complainants and witnesses, such as their physical integrity, mental health, and sexual history – all of which are associated with a high expectation of privacy in society. The protection of this information from disclosure through a public hearing would also reduce the risk of re-traumatizing complainants and witnesses, which is a guiding principle contained in the UCCMS.

A public hearing could also cause harm to the interests of justice from the perspective of a respondent and future complainants. In the case of a respondent, a public hearing that attracts media attention and leads to members of the public expressing their views on the case could jeopardize a respondent’s right to a fair hearing before an independent and impartial adjudicator. In the case of future complainants, a public hearing that injures the reputation of a complainant or witness could discourage the reporting of complaints under the UCCMS or the participation of individuals as witnesses in future UCCMS investigations and arbitration hearings, which would be contrary to the interests of justice. Finally, a public hearing may not be warranted in an arbitration proceeding that is not a de novo hearing, such as a narrow scope of review where the arbitrator is not engaged in fact-finding and is only reviewing the procedural and substantive aspects of the original decision.

In summary, all of the limitations to a public hearing noted by the EHCR in the Pechstein case are applicable to the sport maltreatment arbitration context. However, it may be inappropriate to assume that this will always be the case and, therefore, consideration should be given as to whether a party to an arbitration proceeding should have a right to request a public hearing, subject to the arbitrator’s discretion to reject the request based on the application of the above limitations to the specific context of the hearing.

Consideration should also be given to whether any risks associated with a public hearing could be mitigated by its format and the issuance of a publication ban. For example, in the case of SDRCC doping cases, public attendance in the hearing is limited to listening through an audio link, as opposed to in-person attendance or video link.[56] A publication ban would prohibit any person who attends the hearing from publishing any information about a complainant or witness, and would be less restrictive than the current SDRCC rule that prohibits any attendee of a hearing from disclosing any information obtained during the hearing to a third party, with some exceptions.[57]

Q3: What unique confidentiality rules or exceptions may be needed for the sport maltreatment arbitration context?

If a sport maltreatment arbitration hearing is confidential and closed to the public, then two additional considerations exist. First, what accommodations may be needed to support a minor or vulnerable person who participates in the hearing? Under the SDRCC procedural rules, the only persons permitted to attend a closed arbitration hearing are the arbitrator, the parties, the parties’ representatives and advisors, and witnesses.[58]

However, for the SDRCC Safeguarding Tribunal, an arbitrator can accommodate a person’s vulnerability by allowing a support person to be present or to participate in the hearing.[59] A minor, vulnerable person, and any adult witness who is not a minor or vulnerable person, but over whom a respondent has authority or power, may request this procedural accommodation.[60] As a general rule, this procedural must be granted by the arbitrator, unless the arbitrator believes it would interfere with the proper administration of justice.[61]

The second consideration relates to the publication of the arbitrator’s decision. To ensure a procedurally fair arbitration process, the arbitrator’s decision must be disclosed to the parties so that they know the reasons for the arbitrator’s decision. However, outside of this disclosure to the parties, there are various options for the publication of decisions. For example, a full or summary version of the decision could be published, with or without redactions that anonymize the parties. Alternatively, the publication could be restricted and only involve the disclosure of the decision (full, summary, anonymized) to select third parties on a need-to-know basis.

The central question to any option for disclosing an arbitration decision is identifying the purpose(s) of the disclosure, its relation to any rights or interests of persons who may be impacted by the disclosure, whether any of those rights or interests outweigh the purpose of the disclosure, and whether the purpose of the disclosure can be met by a level of disclosure that least intrudes on the affected rights and interests. For example, in Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution-Institutional Issues), we examined the value of a system of precedent for arbitration decisions in the sport maltreatment context, and how a system of precedent could be enhanced by the publication of arbitration decisions. However, in Chapter 8 (Investigation), we also discussed how the benefits of a system of precedent could be obtained without publishing full arbitration decisions, such as through annotated versions of the UCCMS or SDRCC procedural rules that explain key rules and principles based on arbitration decisions.

An additional purpose of disclosing an arbitration decision could be to assist with the enforcement of a sanction under the UCCMS. However, as discussed in Chapter 7 (Jurisdiction), enforcement of UCCMS sanctions can be effectively achieved by publishing the identity of a respondent, the type of maltreatment they committed, and their sanction, without additional particulars.

With respect to the relevant rights and interests that would be impacted by the disclosure of a decision, many of the considerations for rejecting a request for a public hearing would be relevant and may trump certain purposes of disclosing a decision. Table 10.3 below provides examples of purposes of disclosure and the countervailing considerations.

Table 10.3 Purposes of Disclosing Arbitration Decisions and Relevant Considerations

| Purpose of Disclosing Arbitration Decision | Countervailing Consideration |

|---|---|

|

|

To summarize, the confidentiality of arbitration proceedings raises complex policy considerations that intersect with the rights and interests of the parties involved. With respect to the confidentiality of a hearing, there is a strong rationale for providing a party with a right to request a public hearing, subject to certain limitations. With respect to the publication or disclosure of decisions, several options exist, and the appropriate option requires a balancing of the purpose of the disclosure and the rights and interests of persons likely to be impacted by the disclosure. Table 10.4 below provides a summary of the confidentiality rules for sport maltreatment arbitration proceedings in the United States, the United Kingdom and the SDRCC’s Safeguarding Tribunal.

Table 10.4 Privacy Rules in Sport Maltreatment Arbitration Context

|

United States SafeSport |

United Kingdom National Safeguarding Panel (NSP) |

SDRCC Safeguarding Tribunal |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Arbitration Hearing |

Confidential and closed to the public.[62] |

Confidential and closed to the public, unless a party provides good cause for a more open hearing. Procedural accommodations that allow support persons for minors and vulnerable persons.[63] |

Confidential and closed to the public. Procedural accommodations that allow support persons for minors and vulnerable persons.[64] |

|

Arbitration Decision |

Decision delivered to parties is redacted to remove identifying information about the complainant and witnesses. If the arbitrator concludes that the respondent has not violated the code, then the respondent may request the redaction of their identifying information. Summary of decision can be disclosed to U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee and national sport organizations on a need-to-know basis to assist with enforcement.[65] |

Several options:

|

Several options:

|

5. Substantive Principles of Law for Interpreting the UCCMS

Have you ever read a rule in a sport regulation or a contract that was unclear in its meaning or had more than one possible interpretation? Was the meaning of the rule confusing, in general, or was it only confusing when applied to a unique set of facts? How did you resolve the unclear or ambiguous wording? Did you search for meaning in the text itself or did you seek out an external resource?

Unclear or ambiguous rules in laws, contracts and other documents are a common source of legal disputes. One party may have an opinion on the interpretation of the rule and another party may have a different interpretation. The difference in opinion can be long-standing and pre-date any dispute, or it can arise at the dispute resolution stage when one party is accused of violating the rule and is looking for an interpretation that avoids a finding that a violation occurred.

The focus of this section is on the substantive principles of law that are likely to be applied by arbitrators to resolve disputes involving the interpretation of the UCCMS.[68]

Figure 10.6 Ambiguities in Language

Ambiguities in Language

Ambiguities in Language

Read the two facts listed below and respond to the questions provided in the response tool.[69]

Fact 1: A federal law requires a 10-year mandatory prison sentence in certain cases where the defendant had previously been convicted of crimes “relating to aggravated sexual abuse, sexual abuse, or abusive sexual conduct involving a minor or ward.”

Fact 2: A convicted defendant argues that the qualifier, “involving a minor or ward,” applies not just to the third-listed item (abusive sexual conduct), but also to the first two (aggravated sexual abuse and sexual abuse).

Optional Reading: See the case of Lockhart v. United States, No. 14-8358 (U.S. March 1, 2016). The U.S. Supreme Court rejected the defendant’s interpretation. Interestingly, the courts below the Supreme Court each had differing views on the interpretation of the law.

Scholars have reviewed sport arbitration decisions issued by international and national arbitration institutions to identify patterns in decision-making and categorize the substantive legal principles applied by arbitrators in hearings to determine whether they are specific to sport (and therefore a type of specialized sports law) or just the application of legal principles rooted in domestic legal systems.[70] With some possible exceptions,[71] it can be argued that arbitrators apply legal principles rooted in domestic laws.[72] In the case of the SDRCC, the relevant domestic law to be applied is Ontario law.[73] Thus, the key question is: what sources or general principles of Ontario law will be used by arbitrators to interpret the UCCMS?

Substantive principles of interpretation will be relevant for an arbitrator regardless of their scope of review in a hearing. For example, in a de novo hearing, the arbitrator must interpret the UCCMS and apply it to findings of fact made by the arbitrator. In a narrower scope of review where the arbitrator is reviewing an original decision made by the NIM or a sport organization, the arbitrator must still interpret the UCCMS to determine whether the original decision was reasonable or contained an error. However, there are different sources and principles of Ontario law that arbitrators may rely upon to interpret the UCCMS.

Contract Law Principles of Interpretation

One possible source of interpretive principles is contract law. This requires the arbitrator to interpret the UCCMS as a contract, which it is for the jurisdictional reasons discussed in Chapter 7 (Jurisdiction). Principles of contract interpretation are commonly relied upon by SDRCC arbitrators.[74] Some SDRCC arbitrators have also relied upon principles of contract interpretation based on the use of such principles by CAS arbitrators (see Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution-Institutional Issues) discussion on precedent).[75]

The general principles of contract interpretation focus on determining the intent of the parties and what they intended to agree upon.[76] This involves reading the contract as a whole and giving the words used their ordinary and grammatical meaning, consistent with the surrounding circumstances known to the parties at the time the contract was formed.[77]

However, when an ambiguity in a contract exists that cannot be resolved by applying the general principles above, then the doctrine of contra proferentum applies.[78] Contra proferentum is Latin for “against the offeror” and it provides that an ambiguous term should be interpreted against the interests of the party that drafted the term or requested its inclusion in the contract. The doctrine has been applied by SDRCC arbitrators in past decisions.[79]

In the context of the UCCMS, the general principles of contract interpretation will be helpful for an arbitrator to determine the meaning of a provision whose meaning is disputed. The requirement to read the contract as a whole will allow for careful consideration of the general principles and commitments set out in the UCCMS. In addition, the surrounding circumstances may include any educational or training resources used to educate participants about the UCCMS. However, the application of the doctrine of contra proferentum may be limited to hearings where the relevant sport organization is a party, as it is the sport organization that imposed the terms of the UCCMS into a contract with the respondent, as discussed in Chapter 7 (Jurisdiction).

Statutory Interpretation

Some scholars have criticized the use of contract law principles to interpret sport rules (or even contracts between sport organizations and participants). It is challenging to view the relationship between a sport organization and participant as contractual because of the power imbalance that exists between the two parties. In the context of CAS decisions interpreting the rules and regulations of international sport federations, Foster (2003) notes:

“Although the relationship between an international sport federation and an athlete is nominally said to be contractual, the sociological analysis is entirely different. The power relationship between a powerful global international sporting federation, exercising a monopoly over competitive opportunities in the sport and a single athlete is so unbalanced as to suggest that the legal form of the relationship should not be contractual. Rather like the employment contract, a formal equality disguises a substantive inequality and a reciprocal form belies am asymmetrical relationship.”[80].

As Findlay and Mazzucco (2010) note, this unbalanced power relationship is equally present at the Canadian national sport level between an athlete and their respective national sport organization. Participants have practically no authority to participate in the negotiation of a contract, or a sport policy that is incorporated by reference into a contract. This is not to suggest that a sport organization shouldn’t have control over the rules and regulations it drafts and imposes on participants. In many cases, such as the sport maltreatment context, such control is necessary to ensure the proper implementation of minimum standards and rules for the sport sector.

However, the concern is that because the rules do not take the form of a freely negotiated contract, the principles of contract interpretation may not be the most appropriate method for resolving interpretative disputes. For example, if the principles of contract interpretation are focused on discerning the intent of both parties to the contract, then this becomes a bit of a fiction in the sport context where the sport organization’s rules are imposed unilaterally on one party.

As an alternative to contracts, sport rules can be seen as more similar to legislation (i.e. a statute or regulation made by elected members of government). For example, anti-doping rules, such as the World Anti-doping Code, can be viewed as quasi-legislative in nature.[81] Similar to legislation, sport rules are made by officials (e.g. a board of directors) who are elected by members of the organization. However, a challenge with this interpretation is that not all subjects of a sport organization’s authority are members of the organization. Depending on the type of organization and its level in the organizational structure of the sport system, the members of the organization may be other organizations and not individual participants, such as athletes. This type of membership structure minimizes the democratic accountability of the elected officials to the ultimate subjects of their authority. This concern has led some scholars to characterize the monopolistic authority exercised by sport organizations, particularly at the international level, as undemocratic and illegitimate[82]