9 Dispute Resolution: Institutional Issues

Hilary Findlay

Marcus Mazzucco

Themes

Sports Law

Dispute Resolution in Sport

Sport Arbitration

Learning Objectives

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

L01 Describe the stage at which disputes may arise in the sport maltreatment context;

L02 Describe arbitration and explain how it is different than litigation in courts;

L03 Explain the principles of impartiality and independence in the context of arbitration;

L04 Explain the importance of having diverse and appropriately trained arbitrators to resolve sport maltreatment disputes in a fair and effective manner; and

L05 Explain the value of a system of precedent in arbitration.

Overview

This chapter examines the use of arbitration to resolve disputes arising from investigations into alleged violations of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport. Key issues related to the institutional aspects of arbitration will be considered, including the importance of having impartial, diverse and appropriately trained adjudicators, as well as the value of a system of precedent for arbitration decisions. Existing sport arbitration institutions, including the Court of Arbitration for Sport and the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada, will be used as examples to discuss these issues.

Key Dates

Once an investigation has concluded and a decision has been made about a violation of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS), a dispute about that post-investigation decision may arise.[1] Depending on who conducted the investigation, who made the decision, and the substance of the decision, the nature of the dispute and the parties involved may differ. The parties may involve the complainant,[2] the respondent,[3] the relevant sport organization, and the decision-maker whose ruling on a violation or sanction under the UCCMS is being challenged. In many cases, the decision-maker will be the national independent mechanism (NIM). This chapter examines the availability of private arbitration to resolve disputes in this post-investigation context.[4]

Figure 9.1 Parties Involved in Dispute Resolution

Arbitration

Arbitration is a process whereby parties refer their dispute to a mutually acceptable, knowledgeable, independent person (an arbitrator) to determine a resolution. The parties usually agree beforehand to be bound by the arbitrator’s decision. Further, by agreeing to resolve a dispute by arbitration, the parties generally forego the opportunity to resolve their dispute through litigation in court.

Arbitration is commonly used to resolve disputes in sport as is evident by the creation of sport-specific arbitration institutions at the international and national levels, such as the international Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) and the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC). In the maltreatment in sport context, arbitration is used to resolve disputes arising from investigations, as seen in the United States (U.S.) with the Judicial Arbitration Management Service, in the United Kingdom (U.K.) with the Sport Resolutions’ National Safeguarding Panel, and in Canada with the SDRCC’s Safeguarding Tribunal.

What is arbitration and how does it work? Watch this short video on “Arbitration Agreement Explained by Hesham Elrafei.

Arbitration differs from an internal appeal mechanism that may exist within a sport organization as the resolution of the dispute is handled by a third party that is external to the sport organization. Arbitration also differs from traditional litigation in courts or tribunals as it occurs in a private context and is consent-based. It is consent-based because both parties have agreed, either prior to a dispute or after a dispute has arisen, to resolve their conflict through arbitration. In contrast, litigation tends to be a more adversarial process whereby one party (a plaintiff) seeks to enforce certain legal rights against another party (a defendant), without any prior agreement on that method of dispute resolution. These distinctions are important to understand because in the Canadian sport context, arbitration is considered to be the most effective dispute resolution process.

The consent of the parties to resolve a dispute by arbitration is reflected in an arbitration agreement.

An arbitration agreement can be a standalone agreement entered into by parties after a dispute has arisen, or it can be part of a contract that establishes a legal relationship between two parties prior to any dispute, such as an employment or commercial agreement. For example, in the sport context, an agreement to arbitrate can be incorporated into the policies of the sport organization with which sport participants agree to comply as a condition of participating in the sport or incorporated into a national team agreement between a national sport organization and an athlete (see below for an example of an arbitration clause). However, as previously discussed in Chapter 8 the concept of consent in the sport context can be criticized for being forced or coerced since participants are faced with the option of agreeing to the sport organization’s rules (including those governing the arbitration of disputes) or not participating in the sport.

Example of an Arbitration Clause in a Sport Organization Policy or Contract

“Any dispute arising from or related to this [policy or contract] will be submitted exclusively to the dispute resolution secretariat of the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada and resolved definitively in accordance with the Canadian Sport Dispute Resolution Code, as amended from time to time”.[5]

- More expedient – arbitration avoids any backlog in courts and has flexible procedural rules intended to resolve disputes in the most timely and efficient manner possible, such as procedures for parties to be heard via written submissions, teleconference, or videoconference. For example, SDRCC and CAS arbitrators are able to issue decisions within 24 hours of a hearing.

- Less costly – arbitration services can be offered on a reasonable fee-for-service basis, and the fees may be subsidized in whole or in part in the sport sector through government funding or user fees paid by sport participants. For example, in the case of federally funded sport organizations in Canada, the dispute resolution services of the SDRCC are free-of-charge, except for a filing fee that applies to certain services. In addition, more flexible procedures mean that parties can participate in the arbitration process without legal counsel to reduce costs.

- Less adversarial – arbitration can be less adversarial than litigation because the process is consent-based, which is important if parties need to maintain working relations following the resolution of a dispute. This is especially important in the sport context where the community of participants tends to be small and close-knit.

- Private/confidential – parties can agree to keep arbitration proceedings, and any decision, confidential.

- Jurisdictional clarity – parties can agree on who is subject to an arbitrator’s jurisdiction, what rights can be enforced in arbitration, and what remedies can be sought at arbitration.

The remainder of this chapter explores three key issues relating to the institutional[6] aspects of arbitration in the sport maltreatment context, as set out below:

- Ensuring independence and impartiality in the arbitration process;

- The importance of having diverse and appropriately trained arbitrators; and

- The value of a system of precedent to clarify aspects of the UCCMS and ensure its consistent application.

1. Ensuring Independence and Impartiality in the Arbitration Process

An individual has a fundamental right to an independent and impartial adjudicator. This right is protected in provincial and territorial arbitration legislation that governs private arbitration proceedings in Canada.[7] Independence and impartiality are necessary to ensure public confidence in a dispute resolution system, and are consistent with the guiding principles of the UCCMS that call for a fair and independently-administered process.

The principle of impartiality requires an arbitrator to decide a dispute with an objective and open mind, free from any actual or perceived bias. Actual bias exists where an arbitrator is predisposed to decide a matter in one particular way over another and may arise where the arbitrator has a direct material interest in the outcome or has publicly favoured one outcome over another. For example, in a dispute about the outcome of a soccer match where bad faith or poor refereeing is alleged, an arbitrator would have a direct material interest in the outcome if they had placed a bet on the winner of the match. In contrast, perceived bias may exist where an informed person holds a reasonable suspicion that the arbitrator is or may be biased and cannot decide a matter fairly. This suspicion of bias may be based on contextual factors such as a personal, financial, or other relationship between the arbitrator and individuals participating in the arbitration process. For example, in a dispute involving a sport organization, if the arbitrator is on the board of directors of the organization, then that relationship may lead to a suspicion that the arbitrator is going to decide the dispute unfairly by favouring the sport organization.

The principle of independence refers to an arbitrator’s freedom from the control or influence of others and it is related to the principle of impartiality as independence avoids the appearance of bias. The independence of an arbitrator has several aspects. First, an arbitrator must be independent from the parties to a dispute, including their representatives, and any witnesses in the proceeding. As noted above, the parties to a dispute in the maltreatment context may include the complainant, the respondent, the relevant sport organization and the NIM. While these parties may be involved in selecting an arbitrator to resolve their dispute, that arbitrator cannot have any personal, financial, or business ties to the parties that may jeopardize the arbitrator’s independence and ability to decide matters free from a conflict of interest.

Second, where arbitration services are provided by an institution, such as CAS or SDRCC, the arbitrators must be independent of the institution meaning that they must have the freedom to hear the matter objectively and make a fair decision without fear of losing their tenure and without administrative controls that might interfere with their exercise of discretion. A lack of administrative control would exist where the arbitrator is required to share a draft of their decision with an officer or director of the arbitration institution for the latter’s input before finalizing the decision. Third, where an arbitration institution is involved, the institution must be sufficiently independent from the parties likely to require arbitration services. This final aspect of independence led to structural changes at CAS. From 1984 to 1994, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) administered CAS; however, due to concerns that decisions of CAS could be challenged on the basis that CAS lacked independence where the IOC was a party to a dispute, an independent body – the International Council of Arbitration in Sport (ICAS) – was created to administer CAS.

In the sport maltreatment context, various safeguards are needed to ensure arbitrator independence and impartiality. For the most part, these safeguards are successfully met by existing sport arbitration institutions, as seen from the examples in Table 9.1 below.

Table 9.1 Safeguards for Ensuring Arbitrator Independence and Impartiality in Sport Maltreatment Cases

| Safeguard | Description/Rationale | Examples |

| Private, external administration | To ensure that arbitration services are provided by an entity that is separate from the parties requiring arbitration services | SDRCC– not part of the Canadian government or sport organizations; overseen by a board of directors appointed by federal Minister based on guidelines established in consultation with sport sector.[8] |

| U.S. SafeSport – arbitration services provided by a private company, Judicial Arbitration and Mediation Services (JAMS), that is separate from Center for SafeSport, the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC), and national sport governing bodies (NGBs).[9] | ||

| U.K. National Safeguarding Panel (NSP)– administered by an independent, not-for-profit company, Sport Resolutions, that is separate from NGBs.[10] | ||

| Arbitrator independence from arbitration institution | To ensure arbitrators have security of tenure and independent administrative control | SDRCC– arbitrators have a statutory mandate to be independent from SDRCC;[11] arbitrators are not employees of SDRCC;[12] SDRCC oversight focused on ensuring that arbitrators comply with code of conduct, and not reviewing, changing or overturning the decisions rendered by arbitrators.[13] U.S. SafeSport – arbitrators are “neutrals” of JAMS, not employees.[14] |

| U.K. NSP – arbitrators are appointed for 3-year terms; only have contractual accountability to the Chair of Sport Resolutions that is separate from their adjudicative duties.[15] | ||

| Arbitrator selection | To ensure a fair process to select arbitrators to hear a specific dispute that either involves the agreement of the parties and/or selection by the arbitration institution | SDRCC – parties to agree on arbitrator within certain timelines failing which the SDRCC selects the arbitrator from a roster.[16] |

| U.S. SafeSport – arbitrator selected by JAMS based on short-list that includes input from parties.[17] | ||

| U.K. NSP – arbitrator selected by President of NSP.[18] | ||

| Conflict of interest declaration | To ensure arbitrators declare any actual or perceived conflict of interest that may impact their ability to decide a matter impartially | SDRCC – arbitrator must immediately disclose any interest or relationship that may adversely affect their independence or impartiality.[19] |

| U.S. SafeSport – arbitrator selected must disclose any circumstance that could impact impartiality or independence, including bias, financial interest, personal interest.[20] | ||

| U.K. NSP – arbitrators must disclose anything that might be perceived as a conflict of interest.[21] | ||

| Challenge to appointment | To enable parties to challenge an arbitrator’s appointment if they believe an actual or perceived conflict of interest exists | SDRCC – party may challenge arbitrator on grounds of conflict of interest or reasonable apprehension of bias.[22] |

| U.S. SafeSport – parties can file objection to arbitrator’s continued service based on conflict of interest concerns.[23] | ||

| U.K. NSP – party may challenge selection of arbitrator due to doubts about independence or impartiality.[24] |

Despite the above safeguards, there may be unique considerations for ensuring arbitrator independence and impartiality in the Canadian sport maltreatment context. The first issue relates to the dual function that an institution, such as the NIM, would have if it provides investigative and arbitration services. In the U.S. SafeSport model, this dual function is avoided by having the Center provide investigation services, and a separate and independent entity, JAMS, provide arbitration services. In contrast, the U.K., Sport Resolutions provides both investigative and arbitration services.

The SDRCC has been selected by the federal government to act as the NIM and will provide both investigative and arbitration services relating to participants of federally funded sport organizations. It is absolutely essential that the SDRCC’s arbitration services be separate from any investigative function to ensure independence and impartiality. This may require organizational structures, information technology measures, and human resource policies to ensure an adequate division of functions. For example, when the SDRCC created a pilot project involving an Investigation Unit and the Safeguarding Tribunal, the SDRCC established a policy to ensure a division between these bodies.[25] Only mediators from the SDRCC roster could be members of the Investigation Unit.[26] Conversely, arbitrators wishing to become members of the Investigation Unit would have to resign as an arbitrator before commencing any investigative role.[27] A similar policy will be needed once SDRCC, as the NIM, creates a new Maltreatment Tribunal (or expands the Safeguarding Tribunal) to provide arbitration services to resolve disputes involving post-investigation decisions made by the NIM.

It is not yet known who would provide investigative and arbitration services if the UCCMS is implemented at the provincial, territorial, and local levels of sport. It is possible that SDRCC will outsource investigative and arbitration services to separate, local entities, such as provincial alternative dispute resolution institutes for arbitration services. If this occurs, then the above dual-function concerns would not be applicable.

A second issue concerning independence and impartiality that is relevant to the Canadian sport maltreatment context relates to the selection of arbitrators for hearings. As noted in Table 9.1 above, the selection of an arbitrator to preside over a matter can involve the agreement of the parties. However, where a roster of arbitrators is established specifically to resolve disputes concerning the UCCMS, there is a risk that the parties’ selection of arbitrators may favour a party that repeatedly appears before those arbitrators. For example, the NIM is likely to be a frequent party to arbitration hearings conducted by the SDRCC, and therefore may have an advantage of knowing which arbitrators are more likely to decide in the NIM’s favour. The NIM’s preferred arbitrator may be accepted by the other party to the dispute due to that other party’s unfamiliarity with the arbitration process or a power imbalance that leads the other party to accept the NIM’s choice of arbitrator.

In the context of CAS, this issue has been identified as potentially creating an unfair arbitral process.[28] The unfairness arises because the party whose preferred arbitrator is selected will have an advantage of knowing the arbitrator’s reasoning process and can therefore tailor their arguments to appeal to that reasoning process, more so than the other party who is less familiar with the arbitrator. To mitigate this concern, an arbitration institution should have a greater role in selecting the arbitrator for a hearing. For example, in the U.S., the responsible arbitration body (JAMS) sends the parties a short-list of nine arbitrators. Each party can strike two arbitrators from the short-list.[29] From the remaining arbitrators on the list, JAMS selects the arbitrator to hear the dispute.[30] The SDRCC should seriously consider a similar process for selecting arbitrators to hear disputes involving the UCCMS, provided that the SDRCC’s role as the provider of arbitration services can be adequately separated from its other functions, particularly its investigation and post-investigation decision-making functions.

2. Importance of Appropriately Trained and Diverse Arbitrators

Specialization of Arbitrators

An oft-cited advantage of using arbitration to resolve disputes in sport is having arbitrators who are knowledgeable of the sport system and experts in sports law. This specialization is reflected in the organizational structure of some sport-specific arbitration institutions. CAS, for example, is comprised of several divisions:

- Ordinary arbitration division – to hear disputes as a first instance adjudicator;

- Appeals arbitration division – to hear appeals of decisions made by sport organizations;

- Anti-doping division – to hear disputes concerning anti-doping rules; and

- Ad hoc division – to hear disputes at major international competitions, such as the Olympic Games, Commonwealth Games, and the European Football Championship.

Similarly, SDRCC has an Ordinary Tribunal, Doping Tribunal, a Safeguarding Tribunal, and an Appeals Tribunal (for appeals of Doping Tribunal and Safeguarding Tribunal decisions). The Ordinary Tribunal typically hears disputes after the parties have exhausted any internal process within the sport organization. These disputes can involve team selection, eligibility, discipline, governance, funding, and competition outcomes. The Doping Tribunal acts as the first-instance adjudicator for any anti-doping rule violations alleged by Canada’s national anti-doping organization (the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport) that are contested.

Figure 9.2 SDRCC Tribunals

Within these specialized divisions or tribunals are arbitrators with backgrounds in certain types of sports disputes or aspects relevant to those disputes, such as CAS arbitrators who have a particular knowledge of football (soccer) to adjudicate transfer of player disputes or CAS arbitrators familiar with the science underlying anti-doping disputes.[32] In accordance with CAS procedural rules, these arbitrators are often selected by parties to decide disputes because of their specialized expertise in a given area (see Section 1 of this chapter on the selection of arbitrators in relation to arbitrator independence and impartiality). While this knowledge of the sport system or aspects thereof is undoubtedly helpful for an arbitrator, some scholars have raised concerns about the diversity and expertise of CAS arbitrators to resolve disputes involving violations of human rights, such as discrimination against disadvantaged or marginalized groups.[33]

These types of disputes involve the balancing of competing rights, complex medico-legal and policy issues, and may require an adjudicator to assess the broader societal context of the dispute. It is for this reason that domestic legal systems have specialized courts or tribunals to resolve human rights matters (e.g. provincial or territorial human rights tribunals in Canada, and the European Court of Human Rights), and some scholars have advocated for the creation of specialized arbitration tribunals to hear disputes involving human rights violations in sport.[34] In the absence of such human rights specialization in sport-specific arbitration tribunals, and sometimes in response to unsuccessful outcomes at CAS, some athletes have attempted to bring their human rights concerns to domestic courts.

For example, CAS’s decision to dismiss South African middle-distance runner Caster Semenya’s challenge to World Athletics’ eligibility regulations for females with differences of sex development was widely criticized by the sport community, human rights advocates and medical associations, and led Semenya to bring a challenge under the European Convention of Human Rights to the European Court of Human Rights. Similarly, Canadian cyclist Kristen Worley decided to bring a human rights application under the Ontario Human Rights Code to the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario alleging discrimination against the Union Cycliste Internationale, the IOC and World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) (among others), rather than pursue the complaint to the UCI’s internal arbitral panel, and thereafter CAS.[35]

Unique considerations also apply to the resolution of disputes in the sport maltreatment context. Arbitrators require a specialized knowledge of maltreatment issues to make factual findings or make rulings on the admissibility of evidence that involve assessing the credibility of a witness’s testimony or weighing the relevance of evidence against its potentially harmful impact on a party (see Chapter 11 for a discussion on scope of review options for arbitration and their procedural implications). In Canada, the need for arbitrators to have such expertise is supported by the following guiding principles set out in the UCCMS for determining maltreatment and the imposition of sanctions:

- Expert-informed (the determination of maltreatment and impositions of sanctions will be informed by those with expertise in such areas as sport, child abuse, and the law) – this principle is directly related to the qualifications of arbitrators, and indirectly relates to the ability of arbitrators to understand and assess evidence provided by investigators and expert witnesses during arbitration hearings.

- Trauma-informed (acknowledgement of the physical, psychological and emotional effects of trauma, and the avoidance of re-traumatization) – this principle requires arbitrators to have an understanding of different ways complainants may respond to maltreatment (including making reports) and what procedural safeguards might be needed in an arbitration hearing to protect a complainant from further trauma due to their participation as a party or witness.

- Evidence-driven (evidence of maltreatment required) – this principle requires arbitrators to have the knowledge, skills, and experience to make determinations of maltreatment based on evidence, and to apply those determinations when reviewing or imposing a sanction under the UCCMS.

An examination of international comparators supports the use of arbitrators who have a background or are trained in maltreatment issues. For example, in the U.S. SafeSport model, arbitrators must have experience working as a criminal law judge, district attorney or defence attorney with specific experience in sexual misconduct, as a law enforcement official with specific experience in sexual misconduct, as a social worker, as a Title IX coordinator or investigator, as a guardian ad litem, or have other comparable work experience.[36] In addition, arbitrators are preferred if they have experience involving emotional, physical, and sexual misconduct in sport, and all arbitrators must undergo specialized training.[37] Similarly, in the U.K., National Safeguarding Panel arbitrators have backgrounds in law, social work, offender management, policing, medicine and sport, and must participate in specialized training and development programmes.[38]

With respect to SDRCC arbitrators, the Physical Activity and Sport Act authorizes the SDRCC’s board of directors to make bylaws setting out the qualifications of arbitrators and mediators. However, the SDRCC’s general bylaw does not list any specific qualifications and only references the board’s authority to approve qualification criteria from time to time. The SDRCC website only has a general statement that arbitrators have received intensive training to ensure an intimate knowledge of the Canadian sport system, sport law issues and unique needs of members of the Canadian sport system.[39] However, a recruitment notice for the SDRCC Safeguarding Tribunal specifies that arbitrators must have experience judging or conducting arbitrations relating to human rights issues, family law, workplace harassment / employment law, or criminal law.[40]

Currently, the arbitrators assigned to the SDRCC Safeguarding Tribunal are also assigned to the SDRCC’s other tribunals.[41] This suggests that the arbitrators may have been selected for the Safeguarding Tribunal based on their expertise in sports arbitration in general, as opposed to maltreatment, and that the SDRCC may focus on training its existing arbitrators, instead of recruiting arbitrators who have a specific background in maltreatment issues. The SDRCC should establish qualifications and a recruitment process for arbitrators are appropriately tailored to the sport maltreatment context to ensure that arbitrators have the necessary background, experience and training to decide maltreatment disputes competently, ensure public confidence in the arbitration process, and ensure alignment with the UCCMS guiding principles.

Diversity of Arbitrators

The social diversity of arbitrators is another important consideration. In this context, social diversity refers to arbitrators who represent the relevant social groups in Canadian society, especially those who have historically been excluded from positions of power, such as women, racialized persons, Indigenous persons, persons with disabilities, and members of the LGBTIQA community. Diversity in arbitration is important because it ensure the process is representative of the population it serves and allows for a broader range of perspectives to ensure a fair and effective resolution.

This concept of representativeness can be seen in Canadian sports governance and administration. Over the past few decades, attempts have been made to increase the diversity of boards of directors and executives within sport organizations in Canada to ensure the representation of women and the ultimate subjects of a sport organization’s authority – athletes. For example, in the case of 2021 statistics – the Canadian Olympic Committee (COC), 8/19 directors and 4/8 executives are women, and the board of directors includes two athlete representatives from the COC’s Athletes’ Commission.[42] Similarly, for the Coaching Association of Canada (CAC), 8/15 directors and 1/3 executives are women, and the board of directors includes one athlete member.[43] However, racialized persons are underrepresented in director and executive positions within these organizations. In the case of the COC, only 2/19 directors and 1/8 executives are racialized persons[44] and, in the case of the CAC, only 1/15 directors and 1/3 executives are racialized persons.[45]

A commitment to representativeness in governance structures can also be seen in the SDRCC. Under the Physical Activity and Sport Act, the responsible federal Minister has the authority to appoint directors to the SDRCC board based on guidelines established in consultation with the sport community. The guidelines must provide for the appointment of directors who are representative of the sport sector and the diversity and bilingual character of Canadian society. Formal guidelines do not appear to be published; however, diversity criteria are included on the SDRCC’s website and in SDRCC recruitment notices for new directors with an apparent emphasis on sport sector representation, rather than social diversity.[46] For example, both the website and recruitment notice provide that at least three SDRCC board directors must be athletes, one must be a coach, one must be a director or administrator of a national sport organization, and one must be a director or administrator of a major games organization.[47] The current SDRCC board includes equal gender representation, but only includes one racialized person.[48]

However, the representativeness of an organization is only one benefit of diversity. In the adjudicative context, representativeness, although important to ensure public confidence in a decision-making body, can also be perceived as a formal or superficial aspect of diversity.[49] A more substantive benefit of diversity is that socially diverse adjudicators will have different and non-traditional perspectives on legal and policy issues due to their unique background and experience, including that of marginalization.[50] This becomes important when adjudicators are required to consider the norms and values underlying a particular law and apply it to a novel situation, or exercise discretion when making findings of fact or ruling on the admissibility of evidence.[51] This is especially true in the arbitration context where, unlike courts, arbitrators can have greater flexibility over the scope of their review, the rules of evidence, and the scope of remedies that may be granted. As Lenskyj (2018), citing the work of Menkel-Meadow, notes “diversity among dispute resolvers in terms of gender, ethnicity and special class is essential for democratic representation and for extending the possibility of diverse ideas and approaches to problem solving”.[52]

The need for diversity in the arbitration of disputes involving maltreatment in sport is also reflected in the following commitments expressed in the UCCMS for a system to address and prevent maltreatment in sport.

- All participants recognize that maltreatment can occur regardless of age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, race, ethnicity, Indigenous status or level of physical and intellectual disability and their intersections. Moreover, it is recognized that those from traditionally marginalized groups have increased vulnerability to experiences of maltreatment.

- In recognition of the historic vulnerability to discrimination and violence amongst some groups, and that continues to persist today, participants in positions of trust and authority have a duty to incorporate strategies to recognize systemic bias, unconscious bias, and to respond quickly and effectively to discriminatory practices.

Unfortunately, there is a significant lack of social diversity of among arbitrators within certain sport-specific arbitration institutions, such as CAS and SDRCC. In separate reviews of the CAS, Lenskyj (2018) and Lindholm (2019) found that, amongst arbitrators, men continue to outnumber women, with older white males being overrepresented. This may be explained, in part, by the lack of diversity amongst the ICAS, which governs CAS. ICAS did not achieve gender equality until 2016, some 23 years after its creation.[53] Similarly, the roster of arbitrators for SDRCC’s Safeguarding Tribunal shows an overrepresentation of older white men. Perhaps this too can be explained by a lack of diversity amongst the SDRCC’s board of directors, as mentioned above, as well as a lack of diversity in the broader legal profession.

Nevertheless, this lack of diversity among sport arbitrators should not be accepted as a norm or as inevitable, especially at a time when arbitration mechanisms are expanding to include sport maltreatment cases. Accordingly, SDRCC should consider changes to its qualification requirements and recruitment process for arbitrators to ensure greater social diversity amongst arbitrators to advance the principle of representativeness and expand the knowledge, experience and perspectives brought to the resolution of disputes in the sport maltreatment context.

3. Establishing a System of Precedent to Ensure Clarity and Consistency in the Application of the UCCMS

The doctrine of precedent describes a practice whereby a decision-maker is guided by the past decisions of the same or other decision-makers. For example, if one decision-maker decides a dispute by establishing and applying a certain legal principle or rule to a set of facts, then that legal rule or principle can be relied upon by future decision-makers in resolving disputes with the same or similar facts. In common law legal systems, the doctrine of precedent is known as stare decisis (Latin for “to stand by things decided”).

How Does Precedent Work?

Watch the video Precedent–Legal Studies Terms by Wimble Don on YouTube for a summary of the doctrine of precedent.

The doctrine precedent can be classified in various ways. First, precedent can be categorized based on its binding or non-binding effect. Binding precedent refers to a mandatory requirement to follow past decisions, whereas as non-binding precedent describes an optional ability to follow past decisions. Second, the binding or non-binding nature of precedent can be set out in law (known as de jure precedent) or can be observed in practice based on how decision-makers actually relate to past decisions (known as de facto precedent) – for example, do they naturally follow past decisions or disregard them?

Third, precedent can operate vertically or horizontally. Vertical precedent occurs where a decision made by a decision-making body that is higher than others in a hierarchy acts as a precedent for lower level decision-makers. Horizontal precedent occurs where a decision made by a decision-making body becomes a precedent for that decision-making body in future cases or for other decision-making bodies operating at the same level in a hierarchy.

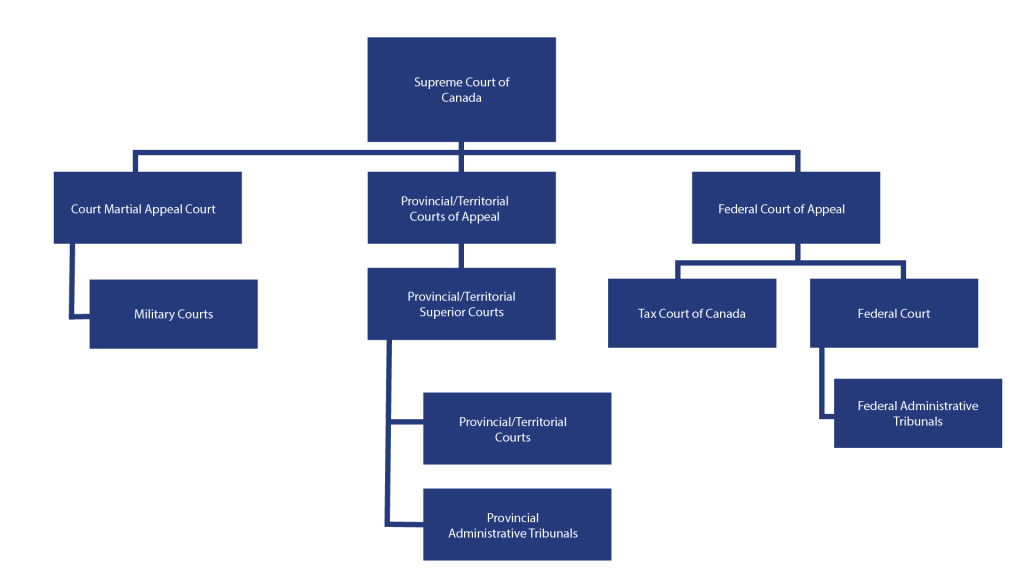

In the Canadian court system, a binding and de jure doctrine of precedent operates vertically when a legal principle or rule established by the Supreme Court of Canada (the highest court in the country) or a provincial or territorial appeal court (the highest court in the province or territory) becomes a precedent that lower-level courts must follow. However, a non-binding and de facto doctrine of precedent also operates horizontally in the Canadian court system when the decision of one court may become a precedent for that court in subsequent cases or other courts at the same level in the hierarchy. See Figure 9.3 for a visual representation of these vertical and horizontal relationships.

Figure 9.3 Hierarchy of Canadian Courts and Tribunals

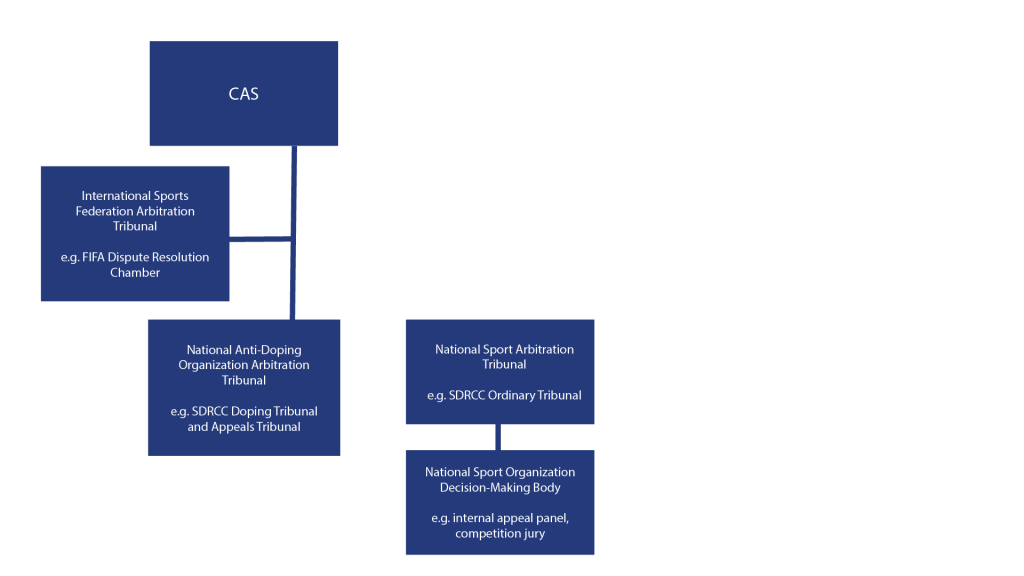

In the sports arbitration context, non-binding and de facto systems of precedent operate horizontally and vertically. For instance, within CAS, legal scholars have found CAS arbitrators are significantly guided by past CAS decisions and will generally follow legal rules or principles articulated in those past decisions, unless they can be differentiated from the present case or a party to the arbitration can demonstrate that the previous CAS decision involved an error.[54] Similarly, SDRCC arbitrators have shown a preference to follow the legal rules or principles expressed in past SDRCC decisions.[55] This is so, despite a rule in the SDRCC’s procedural rules that an arbitrator is not bound by previous decisions.[56] The justifications provided by sport arbitrators when relying on past arbitration decisions as precedent has been respect for fellow arbitrators and the need for consistency in deciding sport disputes.[57]

With respect to the vertical operation of non-binding de facto precedent in sport arbitration, national sport arbitration panels and decision-making bodies within international sport federations have relied on CAS decisions as precedent – either out of respect for CAS arbitrators and their expertise in sports law or because the decisions of these bodies may be appealed to CAS. For example, in Canada, SDRCC arbitrators have applied legal rules and principles established by CAS in disputes involving competition outcomes [58] and anti-doping matters, the latter of which can be appealed to CAS in certain circumstances.[59] Similarly, the Dispute Resolution Chamber (an arbitration tribunal established by the Fédération Internationale de Football Association) has applied legal rules and principles established by CAS in player transfer disputes, since the Chamber’s decisions can be appealed to CAS.[60] See Figure 9.4 for a visual representation of these vertical and horizontal relationships.

Figure 9.4 Decision-Making Hierarchy in Sports System

Systems of precedent are valuable because they ensure consistency and foreseeability in the application of the law. This allows individuals to determine their rights and obligations under the law and either continue or change their behaviour to ensure compliance with the law. For disputing parties, precedent also ensures predictability in how disputes about the interpretation or application of a law will be resolved, and whether it is worthwhile to arbitrate a dispute. In addition, precedent contributes to efficient decision-making as arbitrators will be able to rely on the relevant and applicable legal rules or principles established by previous arbitrators to resolve present-day disputes without “reinventing the wheel”.

As Lindholm (2019) states in his study of CAS decisions, precedent also has forward-looking implications:

“To a body that is about to render a decision, the forward-looking aspect of precedent means having to consider what consequences a contemplated decision in the case at hand will have on future cases. In choosing between different possible rulings, the decision maker must not only consider the outcome of the case in question, but also the outcome of hypothetical future cases where those deciding those cases will tend to adhere to the contemplated decision.”[61]

Lindholm (2019) found that CAS occasionally acknowledges that it is aware of the precedent-setting effect of its decisions and may, for example, consciously attempt to limit a decision’s use as precedent in subsequent cases by highlighting the exceptional nature of its facts.

In the sport maltreatment context, a non-binding system of precedent may be particularly helpful. The UCCMS, like many sport codes of conduct (such as anti-doping rules) is a legalistic document that may be challenging for sport participants to interpret and apply. The UCCMS also includes provisions that might be unclear in their interpretation and application to a particular set of facts. Consider the following examples:

- The definition of “maltreatment” requires an act to be volitional (i.e. of one’s own will or choosing) and to result in harm or potentially result in harm. How should the concepts of volition and potentiality be interpreted and applied?

- The definition of “neglect” includes a lack of reasonable care. What action or inaction is considered “reasonable” in the circumstances? For example, is reasonability assessed from the perspective of the respondent whose conduct is being reviewed or from the perspective of a hypothetical objective third party who finds themselves in the same position as the respondent, or a mixture of both perspectives?

- The definition of “physical maltreatment” requires an act to be deliberate but requires an objective assessment of conduct, which may be challenging to interpret and apply in practice.

- The UCCMS acknowledges that sport-specific differences exist with respect to such aspects as acceptable levels of touch, physical contact and aggression during training or competition, and that these aspects will be considered during the investigative process. However, there may be instances where historically accepted practices are not aligned with best practices, and this misalignment may impact how definitions of maltreatment are interpreted and applied.

- The definition of “power imbalance” includes various examples and presumptions, but these could be difficult to apply in practice where a particular set of facts does not neatly fall within the examples or presumptions (see the Case Study of Miranda v. Canadian Amateur Diving Association discussed below).

One of the guiding principles set out in the UCCMS is harmonization – that is, the consistent application of the UCCMS to all sport participants across Canada. A system of precedent for arbitration decisions in the sport maltreatment context would advance this principle. Arbitrators, parties to disputes, and the broader sport community would benefit from a system of precedent as it would guide their common understanding of the UCCMS and their behaviour when participating in sport or resolving disputes about the UCCMS. However, a challenge with having a system of precedent is that its effectiveness depends on whether arbitration decisions are published (see Chapter 11 for a discussion on the confidentiality of arbitration proceedings).

If arbitration decisions are not published, this means that only the arbitrators and the parties to the arbitration hearings have access to the decisions. This could result in unfairness if one party (e.g. the NIM) frequently appears before arbitration panels and has the benefit of accessing and referring to the panels’ decisions in subsequent cases. However, this concern can be mitigated if the party opposite to the NIM is granted access to the unpublished decision by the arbitrator and given time to consider its application to the current case and present arguments on whether it should be relied upon as precedent. This mitigation strategy could be incorporated into the SDRCC’s procedural rules for arbitration hearings as a requirement that arbitrators must follow and as a right that parties in an arbitration can enforce.

Additionally, if the publication of arbitration decisions is not possible (due to privacy considerations), then the arbitration decisions should be reviewed by the arbitration institution or the NIM on a periodic basis and used to publish commentary regarding the interpretation of certain provisions in the UCCMS and the procedural rules that apply to arbitration proceedings in the sport maltreatment context. Such published commentary would be aligned with the following examples of transparency that already exist in the Canadian sport system:

- Explanatory commentary in the UCCMS that clarifies the drafters’ intentions for certain provisions;

- Explanatory commentary in the World Anti-Doping Code and Canadian Anti-Doping Program that clarify the drafters’ intentions for certain anti-doping rules and the interpretation of those rules by sport arbitrators; and

- An annotated version of the SDRCC’s procedural rules that describes how certain rules have been interpreted by arbitrators in past decisions involving eligibility, discipline, selection, and competition disputes.[62]

Case Study:

Miranda v. Canadian Amateur Diving Association

Miranda v. Canadian Amateur Diving Association is an example of the challenges that may arise in interpreting certain terms (e.g. “coach-athlete relationship”) that seem to have clear meanings at first glance, but can be challenging to apply to a set of facts. The case involved a disciplinary dispute that arose from a sexual relationship between two athletes with a significant age gap (15 years old vs. 32 years old). The older athlete, Miranda, was disciplined by the national sport organization for the sexual relationship, and Miranda appealed the discipline decision to the SDRCC.

The main issue at arbitration was whether Miranda’s actions violated the sport organization’s code of conduct. The code of conduct in place at the time did not prohibit sexual relationships between athletes but did prohibit conduct that was “unreasonable and would bring the sport into disrepute”.

The arbitrator considered whether the age gap between Miranda and the complainant or the existence of a coach-athlete relationship between them violated this prohibition. With respect to the age gap, the arbitrator found that the sexual relationship was not a criminal offence because the complainant was over 14 years of age, and Miranda was not in a position of trust or authority towards the complainant. Further, while the age gap could be considered immoral it could not be used as a justification for misconduct against a vague standard of “bringing the sport into disrepute”. With respect to the existence of a coach-athlete relationship, the arbitrator concluded that no such relationship existed since Miranda was only a coach of the complainant on a temporary five-day basis when the complainant’s regular coach was unavailable two years prior to sexual encounter.

Key Terms

Suggested Assignments

- Stepping into the Arbitrator’s Shoes

Read the case of Miranda v. Canadian Amateur Diving Association described in this chapter. See the arbitrator’s report for more detail on the case. This case would be decided differently today due to changes to Canadian criminal laws regarding the legal age to consent to sexual activity. Pretend that the complainant in this case was 19 years at the time of the sexual encounter with the respondent. Apply the UCCMS to these modified facts and determine whether the respondent violated the UCCMS. (Tip: think about whether sexual maltreatment occurred due to the existence of a power imbalance between the complainant and respondent). While conducting your analysis, consider the following:

-

- What personal or professional experiences in sport, if any, are you drawing upon in your analysis?

- What educational experiences or information, if any, are you drawing upon in your analysis?

- Is there any explanatory commentary in the UCCMS that you find helpful in your analysis? Do you wish there was more commentary to guide your analysis?

Figure Descriptions

Figure 9.1 This figure shows the four main parties involved in dispute resolution. This includes the complainant, respondent, decision-maker, and sport organization all fitting together like four puzzle pieces. [return to text]

Figure 9.2 This figure demonstrates the four different Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC) Tribunals. This includes the Ordinary Tribunal, the Doping Tribunal, the Safeguarding Tribunal, and the Appeals Tribunal. [return to text]

Figure 9.3 This figure demonstrates the hierarchy of Canadian courts and tribunals. At the top is the Supreme Court of Canada, the highest court in the country. Lower-level courts include the court martial appeal court, provincial/territorial courts of appeal, and the federal court of appeal. Military courts are listed as a sublevel of the court martial appeal court. Provincial/territorial superior courts are listed as a sublevel beneath provincial/territorial courts of appeal, with provincial/territorial courts and provincial administrative tribunals listed as sublevels beneath the superior courts. The Tax Court of Canada and federal court are both listed as sub-levels beneath the federal court of appeal, with federal administrative tribunals listed as a sub-level beneath the federal court. [return to text]

Figure 9.4 This figure demonstrates the decision-making hierarchy in the sports system. At the very top is the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS). The CAS is directly connected via vertical operation to the National Anti-Doping Organization Arbitration Tribunal, such as the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC) Doping Tribunal and Appeals Tribunal. The International Sport Federation Arbitration Tribunals such as the FIFA Dispute Resolution Chamber also rely on CAS decisions via a vertical relationship. Another vertical relationship is that of the National Sport Arbitration Tribunal like the SDRCC Ordinary Tribunal with a National Sport Organization Decision-Making Body such as an internal appeal panel, or a competition jury. [return to text]

Sources

A.C. v. FINA, CAS Appeals, No. 96/149

Arbitration Act, 1991, Ontario, Canada.

Associated Press. (2021, May 18). Swim star Sun Yang’s three-day retrial at sports court next week. Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://www.sportsnet.ca/olympics/article/swim-star-sun-yangs-three-day-retrial-sports-court-next-week/

Binner, A. (2021, February 25). Caster Semenya appeals to the European Court of Human Rights. International Olympic Committee. Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://olympics.com/en/news/caster-semenya-appeal-european-court-human-rights

Brenner, S. (2021, April 23). Caster Semenya: ‘They’re killing sport. People want extraordinary performances’. The Guardian. Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2021/apr/23/caster-semenya-theyre-killing-sport-people-want-extraordinary-performances

Canadian Anti-Doping Program (CADP). (2021). Canadian anti-doping program: Part C – Canadian anti-doping program rules. https://cces.ca/sites/default/files/content/docs/pdf/2021-cces-policy-cadp-2021-final-draft-e.pdf

Canadian Cycling Magazine. (n.d.). Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://cyclingmagazine.ca/advocacy/transgender-kristen-worley-settlement-rights/

Canadian Olympic Committee (COC). About us: Governance. Retrieved November 4, 2021, from https://olympic.ca/canadian-olympic-committee/governance/

Canadian Safe Sport Program. (2020). Sport Information Resource Centre: Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS), (5)1, 1-16. https://sirc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/UCCMS-v5.1-FINAL-Eng.pdf

CBC Sports. (2005, December 21). Tennis’ Puerta banned 8 years for doping. Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/sports/tennis-puerta-banned-8-years-for-doping-1.529904

Claudia Pechstein v. Deutscher Olympischer Sportbund (DOSB) & International Olympic Committee (IOC), CAS, No. 10/004

Coaching Association of Canada (CAC). (n.d.a). About CAC: Board of directors. Retrieved November 4, 2021, from https://coach.ca/board-directors

Coaching Association of Canada (CAC). (n.d.b). About CAC: Staff. Retrieved November 4, 2021, from https://coach.ca/staff

Court of Arbitration for Sport. (2021a). Code of sports-related arbitration. https://www.tas-cas.org/fileadmin/user_upload/CAS_Code_2021__EN_.pdf

Court of Arbitration for Sport. (2021b). Arbitration rules: CAS anti-doping division. https://www.tas-cas.org/fileadmin/user_upload/CAS_ADD_Rules__2021_.pdf

Court of Arbitration for Sport. (n.d.). Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://www.tas-cas.org/en/index.html

European Court on Human Rights (2021), Notice regarding Caster Semenya

Findlay, H. & Mazzucco, M. (2010). Degrees of intervention in sport-specific arbitration: Are we moving towards a universal model of decision-making?. Yearbook on Arbitration and Mediation, Penn State University, 2.

Government of Canada. (n.d.). Department of Justice: Age of consent to sexual activity. Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/other-autre/clp/faq.html

Government of Ontario MCCSS. (2016). Standard 5, concluding a child protection investigation. Retrieved December 23, 2021, from http://www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/professionals/childwelfare/protection-standards/standard5.aspx

Gundel v. FEI, CAS decision

Gundel v. FEI, SFT decision

Ingle, S. (2021, February 25). Caster Semenya launches final bid to save career and defend Olympic title. The Guardian. Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2021/feb/25/caster-semenya-career-olympics-european-court-human-rights

Judicial Arbitration Management Service (JAMS). (n.d.a). ADR services: Arbitrators & arbitration services. Retrieved November 4, 2021, from https://www.jamsadr.com/arbitration

JAMS. (n.d.b). Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://www.jamsadr.com

Kaufmann-Kohler, G. (2006). Arbitral precedent: Dream, necessity or excuse?. Arbitration International, 23(3), 357-378. https://cdn.arbitration-icca.org/s3fs-public/document/media_document/media01231914308713000950001.pdf

Lenskyj, H. (2018). Gender, athletes’ rights, and the Court of Arbitration for Sport. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Lex Animate Law Visualized | Hesham Elrafei. (2021, April 28). Arbitration Agreement Explained | Lex Animate by Hesham Elrafei [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CzLiJvLitm4

Lindholm, J. (2019). The Court of Arbitration for Sport and its jurisprudence: An empirical inquiry into lex sportiva. T.M.C. Asser Press.

Mayer v. Canadian Fencing Federation, SDRCC Ordinary, No. 08-0077

Miranda v. Canadian Amateur Diving Association (2005), SDRCC decision. http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/resource_centre/pdf/English/402_SDRCC_05-0030.pdf

Mutu and Pechstein v Switzerland (2018), ECHR, (Applications no. 40575/10 and no. 67474/10

Nishikawa, S. Y. (2009). Diversity on adjudicative administrative tribunals: An integrative conception. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Patel, S. (2021). Gaps in the protection of athletes gender rights in sport—a regulatory riddle. International Sports Law Journal 21, 257–275.

Physical Activity and Sport Act, SC 2003, c 2. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/p-13.4/20030702/P1TT3xt3.html

Pound, R. (2015). Sports arbitration: How it works and why it works. McGill Journal of Dispute Resolution, 1(2), 76-85. https://mjdr.openum.ca/files/sites/154/2018/05/010276_Pound_SportsArbitration.pdf

Puerta v. ITF (2006), CAS decision, A/1025

R. v. International Equestrian Federation (1999), CAS, No. 99/A/246

Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC). (n.d.a). Dispute resolution secretariat (tribunal): Arbitrators and mediators. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/dispute-resolution-arbitrators

SDRCC. (n.d.b). Board of directors. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/about-bod

SDRCC. (n.d.c). Retrieved December 23, 2021, from http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/home

SDRCC. (2005). Miranda v. Canadian Amateur Diving Association summary. http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/resource_centre/pdf/Summary/401_SDRCC%2005-0030-summary.pdf

SDRCC. (2006). Draft arbitration clause. http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/documents/Template_Arbitration_Clause_EN.pdf

SDRCC. (2014). Code of conduct for SDRCC mediators and arbitrators. http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/documents/ROSTER_CODE_OF_CONDUCT_adopted_27-Sep-2013_EN.pdf

SDRCC. (2015a). Bylaw no. 1, as amended. http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/documents/General_By-Law_No_1-2015_Board_Approved_ENG.pdf

SDRCC. (2015b). Procedural code.

SDRCC. (2018a). Complaints process policy. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/documents/Complaint_Process_Policy-EN_2018_Final.pdf

SDRCC. (2018b). Investigation unit: Investigation guidelines. Retrieved November 8, 2021, from http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/documents/Investigations-Investigation_Guidelines_EN_Final.pdf

SDRCC. (2021a). Procedural code.

SDRCC. (2021b). Call for applications for arbitrators and mediators. http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/documents/SDRCC_2021_Roster_Call_for_Applications_EN.pdf

SDRCC. (2021c). Nomination opportunity. http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/documents/SDRCC_-_Nomination_Opportunity_2021_EN_Final.pdf

Sport Resolutions. (2020a). Panel code of conduct. Retrieved November 4, 2021, from https://www.sportresolutions.com/images/uploads/files/E_2_-_Panel_Code_of_Conduct.pdf

Sport Resolutions. (2020b). Child safeguarding policy. Retrieved November 4, 2021, from https://www.sportresolutions.com/images/uploads/files/D_11_-_Child_Safeguarding_Policy.pdf

Sport Resolutions. (2021a). Who are we?: About sport resolutions. Retrieved November 3, 2021, from https://www.sportresolutions.com/about-us/who-we-are/overview

Sport Resolutions. (2021b). Panels: Join our panels. Retrieved November 4, 2021, from https://www.sportresolutions.com/about-us/panels/join-our-panels

Sport Resolutions. (2021c). 2021 NSP procedural rules. Retrieved November 4, 2021, from https://www.sportresolutions.com/images/uploads/files/D_2_-_2021_NSP_Procedural_Rules.pdf

Strasbourg Observers. (2018, November 30). Mutu and Pechstein v. Switzerland: Strasbourg’s assessment of the right to a fair hearing in sports arbitration. Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://strasbourgobservers.com/2018/11/30/mutu-and-pechstein-v-switzerland-strasbourgs-assessment-of-the-right-to-a-fair-hearing-in-sports-arbitration/

U. S. Center for SafeSport. (n.d.). SafeSport Code. Retrieved December 5, 2021, from https://uscenterforsafesport.org/response-and-resolution/safesport-code/

West, D. (2019). Revitalising a phantom regime: The adjudication of human rights complaints in sport. International Sports Law Journal 19, 2–17.

Wimble Don. (2016, June 17). Precedent – Legal studies terms [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tkh8qs-o3OI

World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). (2021). World anti-doping code 2021. https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/2021_wada_code.pdf

Worley v. Ontario Cycling Association, 2016 HRTO 952 (CanLII)

- Disputes may also arise from temporary or provisional measures issued against a respondent during an investigation or prior to a post-investigation decision. A respondent may wish to challenge the issuance of these provisional or temporary measures ↵

- In this chapter, “complainant” refers to the individual who reports or files a complaint about another person’s alleged violation of the UCCMS, including an individual who is the subject of alleged maltreatment ↵

- In this chapter, “respondent” refers to individual who is alleged to have violated the UCCMS ↵

- Other types of dispute resolution may be incorporated into the investigation stage of the process, including resolution facilitation and mediation ↵

- SDRCC, 2006 ↵

- “Institutional” refers to the structure and operations of an organization that provides arbitration services ↵

- For example, see section 11 of Ontario’s Arbitration Act, 1991 ↵

- Physical Activity and Sport Act, 2003 ↵

- U.S. Center for Safe Sport, 2021 ↵

- Sport Resolutions, 2021a ↵

- Physical Activity and Sport Act, 2003 ↵

- SDRCC (2015a), Bylaw no. 1, as amended, http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/documents/General_By-Law_No_1-2015_Board_Approved_ENG.pdf ↵

- SDRCC, 2018a ↵

- JAMS, n.d.a ↵

- Sport Resolutions, 2021b ↵

- SDRCC, 2021a ↵

- U.S. Center for Safe Sport, 2021 ↵

- Sport Resolutions, 2021c ↵

- SDRCC (2014), Code of Conduct for SDRCC Mediators and Arbitrators, http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/documents/ROSTER_CODE_OF_CONDUCT_adopted_27-Sep-2013_EN.pdf ↵

- U.S Center for Safe Sport, 2021 ↵

- Sport Resolutions, 2020a ↵

- Existing source: SDRCC (2021a), Procedural Code, http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/documents/Code_SDRCC_2021_-_Final_EN.pdf ↵

- U.S. Center for Safe Sport, 2021 ↵

- Sport Resolutions, 2021c ↵

- SDRCC, 2018b ↵

- SDRCC, 2018b ↵

- SDRCC, 2018b ↵

- Lenskyj, 2018 ↵

- U.S. Center for SafeSport, 2021 ↵

- U.S. Center for SafeSport, 2021 ↵

- ECHR, 2021 ↵

- Pound, 2015 ↵

- Patel, 2021; West, 2019 ↵

- Patel, 2021; West, 2019 ↵

- Kristen Worley v. UCI, 2016 ↵

- U.S. Center for SafeSport, 2021 ↵

- U.S. Center for SafeSport, 2021 ↵

- Sport Resolutions, 2020b ↵

- SDRCC, n.d.a ↵

- SDRCC, 2021b ↵

- SDRCC, n.d.a ↵

- COC, 2021 ↵

- CAC, n.d.a; CAC, n.d.b ↵

- COC, 2021 ↵

- CAC, n.d.a; CAC, n.d.b ↵

- SDRCC, n.d.b; SDRCC, 2021c ↵

- SDRCC, n.d.b; SDRCC, 2021c ↵

- SDRCC, n.d.b ↵

- Nishikawa, 2009 ↵

- Nishikawa, 2009 ↵

- Nishikawa, 2009 ↵

- Menkel-Meadow, n.d. as cited in Lenskyj, 2018, p. 19 ↵

- Lenskyj, 2018 ↵

- Lindholm, 2019; Kaufmann-Kohler, 2006 ↵

- Findlay & Mazzucco, 2010 ↵

- SDRCC, 2021a ↵

- For example, see A.C. V. FINA, 1996 and Mayer v. Canadian Fencing Federation, 2008 ↵

- For example, see Stewart v. Wrestling Canada Lutte, 2014 ↵

- See Canadian Anti-Doping Program (2021), rules 13.2.3.1 and 13.2.3.2. ↵

- Lindholm, 2019 ↵

- Lindholm, 2019, p. 106 ↵

- SDRCC, 2015 ↵

A process whereby parties refer their dispute to a mutually acceptable, knowledgeable, independent person (an arbitrator) to determine a resolution.

Requires an arbitrator to decide a dispute with an objective and open mind, free from any actual or perceived bias.

Refers to an arbitrator’s freedom from the control or influence of others and it is related to the principle of impartiality as independence avoids the appearance of bias.

The determination of maltreatment and imposition of sanctions will be informed by those with expertise in such areas of sport, child abuse, and the law.

Acknowledgement of the physical, psychological and emotional effects of trauma, and he avoidance of re-traumatization.

Evidence of maltreatment is required.

Arbitrators who represent the relevant social groups in Canadian society, especially those who have historically been excluded from positions of power, such as women, racialized persons, Indigenous persons, persons with disabilities, and members of the LGBTIQA community.

When the diversity of an organization, in terms of its governance or membership, represents the diversity of the population it serves.

Practice whereby a decision-maker is guided by the past decisions of the same or other decision-makers.

Refers to a mandatory requirement to follow past decisions.

Describes an optional ability to follow follow past decisions.

Occurs where a decision made by a decision-making body that is higher than others in a hierarchy acts as a precedent for lower level decision-makers.

Occurs where a decision made by a decision-making body becomes a precedent for that decision-making body in future cases or for other decision-making bodies operating at the same level in a hierarchy.

Volitional acts that result in or have the potential to result in physical or psychological harm. All types of "physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligence and commercial or other exploitation, which results in actual or potential harm to health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power” (World Health Organization, 2010).

The omission of care; failing to enact a duty of care; failing to provide the necessities of life.

Requires an act to be deliberate but requires an objective assessment of conduct, which may be challenging to interpret and apply in practice.

The consistent application of the UCCMS to all sport participants across Canada.

Self-Reflection

Self-Reflection

Case Study:

Case Study: