8 Investigations

Hilary Findlay

Marcus Mazzucco

Themes

Investigations

Procedural Fairness

Duty to Report

Learning Objectives

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

L01 Describe the purpose of an investigation;

L02 Describe the stage at which an investigation occurs and its potential scope;

L03 Describe the key procedural protections for an investigation;

L04 Identify safeguards to prevent a biased investigation; and

L05 Explain why an investigation into alleged sport maltreatment may occur in parallel to criminal or child protection investigations.

Overview

This chapter examines the investigation of alleged maltreatment under the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS). It situates the investigation stage within the larger process of responding to allegations of maltreatment and explores the appropriate scope of an investigation. It also discusses the importance of incorporating procedural protections into the investigation to ensure a fair and unbiased process. Finally, it explores the intersection of reporting and investigative processes with parallel systems under provincial and territorial child protection laws and Canadian criminal laws.

Key Dates

Situating the Investigative Phase

An investigation into an allegation of maltreatment can only occur following the formal reporting of a complaint or allegation. Formal reporting of an allegation of misconduct is distinguished from disclosure of an incident. Disclosure relates to the sharing of an experience, perhaps to a friend, trusted confidant, sport organization or to a third party. A disclosure does not initiate an investigation without the filing of a formal report.[1]

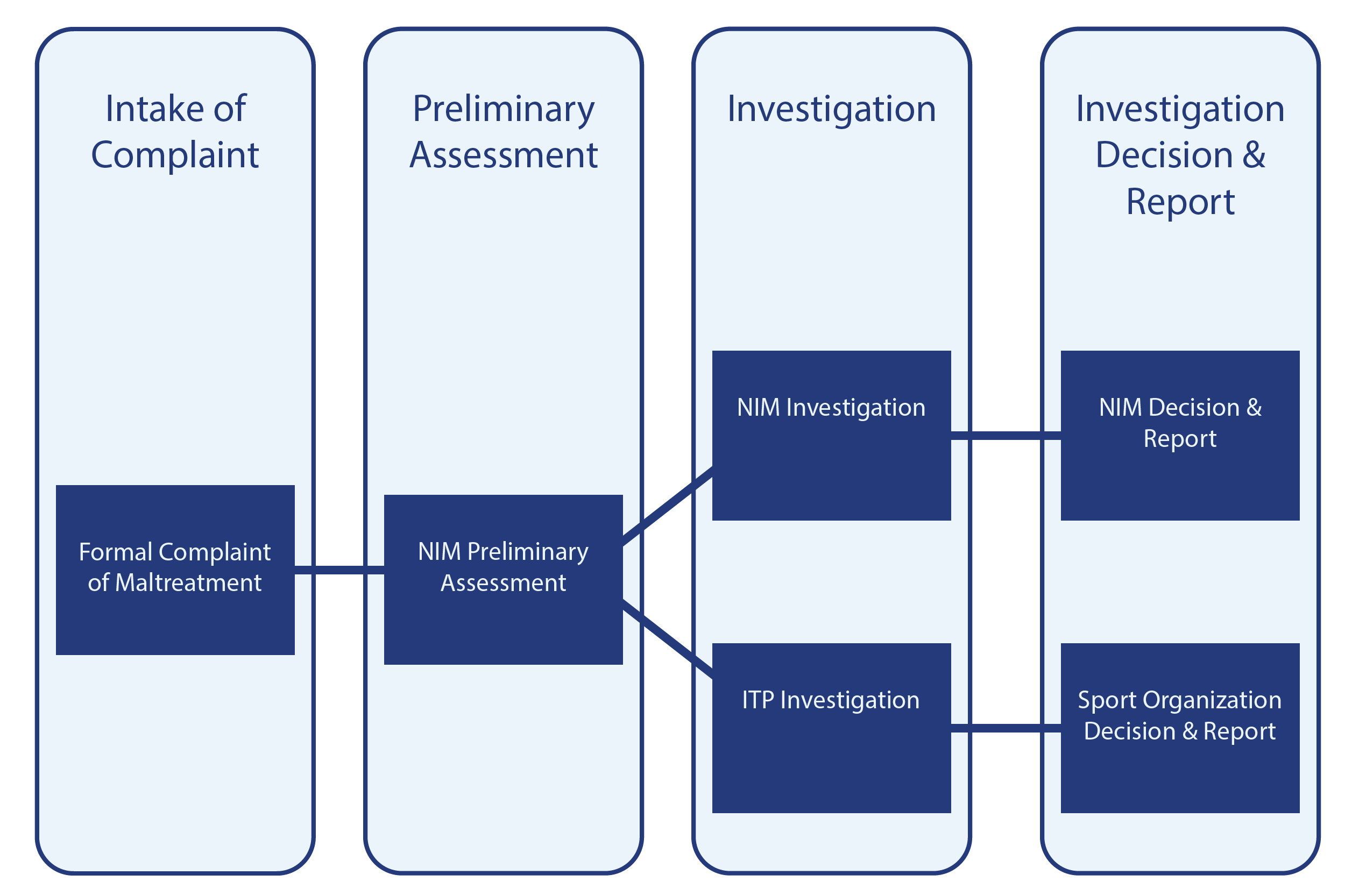

Following the envisioned process under the direction of the National Independent Mechanism (NIM), once a formal complaint has been reported through a dedicated online web portal, a preliminary assessment is made to determine whether the NIM has jurisdiction over the complaint.[2] Jurisdiction refers to the sphere of activity over which an organization’s or individual’s authority extends (jurisdiction was explored previously in Chapter 7).

Where jurisdiction is confirmed, the complaint proceeds to the next step of the assessment to determine where the complaint should be directed. There are two possible options:

Option 1: The complaint stays with the NIM and is resolved internally through an investigation conducted by the NIM and a decision made by the NIM; or

Option 2: The complaint is directed to the independent third party (ITP) used by the sport organization (which could be the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC) or some other body or individual), with oversight by the NIM.

Which path a complaint will take will be determined based on a number of considerations but a key one will be the severity of the complaint. Conduct that carries a sanction of permanent ineligibility should be dealt with using the internal NIM process. Conduct of lower risk and with the possibility of informal resolution is better dealt with through the sport organization’s independent processes, but with continuing oversight by the NIM. However, if the ITP finds that the facts reveal that the alleged conduct is more serious than originally assessed, or the investigation has become too complex for it to complete, it can request that the matter be transferred back to the NIM.

Figure 8.1 Pathway of a Complaint in the Investigative Phase

Whether the complaint is dealt with internally by the NIM or through the sport organization’s own independent process, the next significant stage of the process is the investigative stage. The investigative process is the focus of the remainder of this chapter.[3]

The role of the investigator as fact-finder is to build a body of relevant and admissible evidence that will be useful eventually in confirming or refuting incidents related to the allegations. The investigation can be broken down into three main phases:

Phase 1: Information gathering and analysis

Phase 2: Determination to accept or reject the complaint

Phase 3: Report writing

Phase 1: Information Gathering and Analysis

The first phase of the investigation focuses on gathering information pertinent to the complaint. This will include interviews with the complainant and respondent in particular, as well as any pertinent witness, and reviewing documents, including formal documents of the organization (e.g., policies and pertinent regulations) and other written and digital material.

The scope of the information gathering is defined by the complaint and the UCCMS. The complaint sets out the alleged misconduct and the policy defines conduct constituting maltreatment. The investigation should be limited to the allegations made in the complaint. If there are multiple respondents, each should be accorded their own investigation led by separate investigators.[4] Where multiple complaints of a common nature are brought against a single respondent, it may be appropriate (and procedurally efficient) to have one investigation that examines the complaints.

Information versus Evidence

Information and evidence are similar, but not the same. Evidence is a certain type of information – it is information that is ultimately put before a decision-maker. It is used to prove a fact, disprove a fact, or support or contradict an argument. Evidence is usually verbal testimony, written documentation or material objects that are offered to prove the existence, or non-existence of a fact.

Evidence can also be described as information that has been judged or filtered. The purpose of these filters is to:

- Determine if the information should be accepted or rejected in the decision-making process; and

- If the information is accepted, placing a value or weight on the information.

Not all information is evidence, and not all evidence can be accepted and given substantial weight.

Types of Evidence

The link between evidence and the incident can be direct (also known as primary evidence) or indirect. Indirect evidence can be hearsay or circumstantial (see Figure 8.2 below for an interactive exercise).

1. Direct Evidence

Direct evidence pertains to the incident itself – a direct examination of an object, a video recording of an event, and an account from an eyewitness, are all examples of direct evidence.

2. Indirect Evidence

Indirect evidence is evidence from which one must draw an inference about the incident in question. A photograph taken just before or after the incident, a letter from someone describing an incident, and a witness who said they saw someone in the vicinity of the alleged incident would be examples of indirect evidence.

3. Hearsay Evidence

Hearsay evidence is third party evidence. Person A tells person B something and person B tells the investigator what person A told them. The reliability of hearsay evidence is always suspect because the real source of the information isn’t available to be questioned on it.

This does not mean that hearsay evidence is worthless. Careful questioning of the witness or corroborating the information by questioning other witnesses can help the investigator judge credibility of witnesses and possibly reveal insincerity or other motives. As well, hearsay can always be given an appropriate weight (that is, lesser) relative to other forms of evidence.

4. Circumstantial Evidence

Circumstantial evidence is evidence that is not based on actual personal knowledge or observation of the facts in issue, but rather of other facts from which deductions and inferences are drawn and thereby indirectly suggesting the facts sought to be proved. Circumstantial evidence means that the existence of principal facts is only inferred from circumstances.

5. Corroborative Evidence and Contradictory Evidence

As the terms suggest, the former is evidence that supports, strengthens or confirms other evidence, while the latter is evidence which does the opposite. These types of evidence may be seen as secondary to the main evidence substantiating an issue or a fact. Clearly, less weight is put on this evidence than on direct evidence – nevertheless, even a small aspect of corroborating evidence or contradictory evidence can be very important because it may be sufficient to establish the fact in a certain way.

Figure 8.2 Types of Evidence Matching Exercise

Credibility of Witnesses

An important factor, which must be considered when evaluating evidence, is the credibility of its source – that is, the quality in a witness that renders their evidence worthy of belief. Some of these qualities are:

- Good reputation for directness and veracity;

- Intelligence;

- In a position to have knowledge of the circumstances;

- Good powers of observation and memory recall;

- Ability to describe events clearly and succinctly; and

- Disinterested position in relation to the matter in question (i.e. no vested interest).

Common sense enters into the assessment of a witness’ credibility – their evidence must make sense and seem reasonable to the ordinary person. Whether a witness is credible can have an enormous bearing on the value of their evidence, particularly as it might relate to evidence from other sources. The credibility of the witness may make their evidence determinative – even where the evidence is indirect or circumstantial.

Phase 2: Determination to Accept or Reject the Complaint

The second phase of the investigation is the determination to accept or reject the complaint. The job of the investigator is to sift through all the sources of evidence and, using their logic, analysis of the facts, good judgment, and common sense, make a recommendation or conclusion based on what seems most probable.

Phase 3: Report Writing

The third phase of the investigation is report writing. Writing reasons for findings of facts is a very good way to force the investigator through the process of fact-finding in a structured fashion. The final report should be fair, balanced and objective. The report should contain the following:

- A concise description of the issues that were investigated based on the investigator’s mandate;

- The sources of information used to explore the issues (e.g. documents reviewed and witnesses interviewed);

- A factual summary of each interview;

- A statement of the facts that were established through the investigation;

- A summary of any discrepancies or contradictions in the facts; and

- A note of any information that could not be confirmed through a review of documents or interviews with witnesses.

Depending on the nature and scope of the investigation, the investigator’s report could make one of the following recommendations:

- That the complaint has not been substantiated and the complaint is without merit; or

- That the complaint is substantiated by the facts and the matter should proceed to the next step of the process (i.e., the post-investigation decision).

Procedural Fairness

Procedural fairness refers to the procedures that protect the rights or interests of a person who is the subject of an organization’s decisions, such as findings of fact made during an investigation or a post-investigative decision. At the most basic level, procedural fairness requires notice to the person of an impending decision, the ability for the person to make representations prior to a decision being made, and an unbiased decision-maker. However, procedural fairness is a flexible concept, and the specific procedures required to ensure a fair process will vary depending on various factors, including the nature of the decision being made, the severity of the consequences of a decision, the impact of the decision on the person and the finality of the decision.

When adapting to each situation, investigators should apply the following fundamental principles:

The Respondent’s Right to Notice

The respondent has the right to know the totality of the allegation(s) made by the complainant and the potential consequences if the complaint is founded, and the right to be afforded a reasonable opportunity to respond to them.

Can an investigation proceed if the complainant wishes to remain anonymous?

This can be tricky. In order to make a full response to the allegations, the respondent needs to know to what they are responding. Who brought the complaint may be an important part of the response; however, there is not an absolute right to know the names of witnesses or have access to their witness statements.[5] Yet, respondents should be given accurate information of what is being alleged, including details such as the place, time and details of the alleged incident(s). Ultimately, it is a matter of balancing the need to protect the identities of the complainant and certain third party witnesses and the right of the affected person to a fair investigative process.

In the US SafeSport model,[6] a complainant may request that personally identifiable information not be shared with the respondent, and the Center for SafeSport will seek to honour that request. However, the Center may not be able to proceed with an investigation if the complainant requests anonymity.

The Right to Be Heard

There are two times during the investigation when the respondent should be given an opportunity to be heard: during the fact-finding phase and in response to the investigator’s decision.

Investigation Phase

Both the complainant and respondent should, independently, be given the opportunity to present their version of the facts to the investigator, identify witnesses to the investigator and submit any documentary evidence each feels would be useful to the investigation. They should also have an opportunity to review statements they have made to the investigator in order to confirm their accuracy. Likewise, a draft of the investigation report should be provided to each party for their review and feedback.[7]

Other witnesses interviewed during the investigation process may request to have access to their own statements to verify their accuracy. The investigator may wish to have witnesses acknowledge (in writing) the accuracy of their statement.

Decision-Making Phase

Once an investigation has concluded, an organization (NIM or sport organization) will need to make a decision about whether to accept the investigative findings and, where the accepted investigative findings identify a violation of the UCCMS, issue an appropriate sanction. This post-investigation decision-making phase must also be procedurally fair with prior notice given to the complainant and respondent, and an opportunity for both parties to make submissions to the decision-maker. The right to make submissions may be formal or less formal depending on the seriousness of the alleged maltreatment and potential consequences. For example, where the alleged maltreatment would result in a lifetime suspension of a respondent, they should be given an oral hearing via teleconference, videoconference or in-person to present their submissions to the decision-maker.

Question: Should submissions during an investigation be in writing or done orally (in-person, by video conference or by teleconference)?

The SDRCC Investigation Guidelines[8] encourage investigators to use virtual meeting methods to conduct interviews. In the U.K., a body retained by sport organizations to conduct safe sport investigations (Sport Resolutions)[9] recommends the use of written and signed witness statements during investigations. Where credibility is an issue, body movements, general demeanour and facial expressions can be important to assess credibility, making some form of face-to-face interaction useful. Similarly, in complex matters, engaging with a witness may allow more opportunity to clarify facts. The procedure selected may be a hybrid of written and oral components, such as the exchange of written submissions followed by a video or teleconference or in-person meeting that allows the respondent to answer questions or clarify issues raised by the investigator based on the written materials.

The Right to an Independent and Unbiased Investigator

Independence is often associated with institutional safeguards that allow investigators to be free from external pressures when making their decisions. Safeguards can include ensuring the neutrality in the appointment of the investigator and the absence of pre-existing professional or business relationships between the investigator and parties that could influence the autonomy of the investigative process. The SDRCC Investigation Guidelines[10] address the independence of the investigator throughout the process:

- By avoiding situations where an investigator is a frequent investigator of maltreatment involving a particular sport organization;

- By ensuring a clear separation between investigators and arbitrators in terms of appointments and oversight,[11] which is by an advisory committee led by an SDRCC board member unaffiliated with overseeing the arbitration services, and by establishing a clear separation between investigator and the administrative role of SDRCC so as to avoid any interference or apprehension of interference by SDRCC management.

Throughout the investigation process itself, a number of steps are taken to ensure continued independence and impartiality of the investigator:

- Parties do not participate in the appointment of the investigator; the SDRCC makes the appointment;

- An investigator must perform a conflict of interest check with the parties and sign a declaration of independence;

- If either party objects to the appointment, the investigator must step down;

- Investigators must comply with the SDRCC code of conduct for investigators;

- Investigators must report conflicts of interest and as they arise;

- In the event of a conflict of interest, the investigator must resign or seek the express permission from the relevant organization (e.g., NIM or sport organization) to continue; and,

- Parties may raise concerns about a lack of independence or impartiality of the investigator (however, concerns must be raised right away or a party will be deemed to have waived the right to object later).

An unbiased or impartial investigator, particularly one with decision-making authority, is a fundamental principle of procedural fairness. Investigators must be impartial, free from any conflict of interest, and must approach matters under investigation with an “open mind”. There are two types of bias: actual bias, and perceived or reasonably apprehended bias.

- Actual bias exists where one is predisposed to decide a matter in one particular way over any other. Such a decision-maker has a “closed mind” and is unable to consider a perspective or consideration that differs from their own predeterminations. Actual bias often exists where a decision-maker has a direct interest in the outcome or has publicly favoured one outcome over another.

- Perceived bias is not as clear-cut or obvious as actual bias and is often determined based on contextual factors that consider relationships between the decision-maker and affected persons or other factors that may exist. It is not the mere existence of a relationship, or presence of other factors, that creates the impartiality itself, but rather the extent to which the relationship or other factor influences, or is perceived to influence, the decision-maker. For perceived bias to exist, the relationship or other factor contributing to the apprehension must be consequential and influential.

Bias and conflict of interest are often used interchangeably. A conflict of interest occurs where a party is involved in multiple interests and serving one of those interests could involve simultaneously working against one of the other interests. The conflicting interest could involve any number of things including a financial interest, one’s reputation, a relationship, or access to knowledge of some sort. A person’s involvement in the vested interest raises a question of whether their actions, judgment or decision-making can be unbiased. The conflict is the situation; the bias is the actual or perceived prejudicial behaviour due to the situation. When such a situation occurs in the context of an investigation, the investigator should remove themselves and avoid any engagement in the matter.

For example, if the appointed investigator has a personal or business relationship with one of the parties, there could be the perception of bias in that the investigator may favour that party. As another example, where the investigator is being paid directly by the sport organization and the complaint is against the organization, there could be a perception that the investigator might favour the party paying the bill.[12] Where an investigator has publicly commented on the situation being investigated, or a similar situation, and distinctly favoured a particular perspective, an actual bias may exist and the investigator should excuse themselves from the investigation.

The investigator must maintain an open mind through all phases of the investigation. The SDRCC adjudicator in McInnis[13] (see the case study below – McInnis v. Athletics Canada) summed up the investigator’s role highlighting the impartial and unbiased approach that must be maintained:

“The role of an investigator is always to conduct an impartial investigation of the facts giving rise to the complaint. It is not the investigator’s role to prove a case. Investigators should enter the investigation with an open mind of ‘what does the evidence show occurred’ and should not try to prove the allegations and tailor the evidence to support their ‘theory of the case’. The only theory is what the evidence shows. The investigator should not make up their mind until the last witness is interviewed and the last document reviewed. Of course, as the evidence develops there is nothing improper in gathering corroborating evidence as long as anything that does not support a finding is given equal consideration.”

In Practice:

Bias on the Team

A national team coach is also the head coach of a university’s varsity team. A number of the coach’s varsity players have been members of the national team for several years and are vying for a spot on the current national team. The national team selection policy states that the national team coach and assistant coach will select a slate of players, which will then be reviewed and either confirmed or rejected by the National Team Committee, a committee made up of three members of the national sport organization.

An allegation of bias is made by a player who does not play on the varsity team but is seeking selection on the national team. The player is concerned that the national team coach will favour athletes from the varsity team.

Do you think this is an example of bias? Is it perceived bias or actual bias? What steps might you take to avoid bias?

The above scenario was the situation in the SDRCC case of Wilton v. Softball Canada.[14] Wilton was an elite softball athlete vying for selection to Canada’s national softball team competing at the 2004 Summer Olympic Games. Based on an assessment of performance statistics and players’ strengths and weaknesses, Wilton was selected as an alternate by the national team coach. The decision was then reviewed and supported by only the chair of Softball Canada’s National Team Committee (NTC).

The adjudicator found that the coach was not biased but that the second part of the selection process wherein the NTC as a whole, not just the chair of the committee, was to review and either confirm or reject the selected players. The adjudicator ordered a meeting of the full NTC, including the athlete representative, to hear a presentation by the head coach of his proposed team selection and rationale for his recommendations.

This scenario is an example of how a situation that may present a conflict of interest can be structured to avoid it. The adjudicator found no compelling evidence that the national team coach would jeopardize the chances for success at the Olympic Team just to have more university team members on the national team. However, it was acknowledged that a coach who is more familiar with one player over another would choose the known player over a lesser-known player. Having the NTC oversee and review the selection and, in fact, have ultimate authority to make the selection was intentionally set up to counter this, and other possibilities related to a perceived possible conflict of interest.

In Practice:

Bias in the Organization

Two people are running for election to the position of president of a national sport organization. Person A is the current president and member of the Board of Directors of the organization. Person B is a member of the Board of Directors of an organization doing business with one of the provincial sport organization members of the national organization. The relationship could breach the national organization’s conflict of interest policy. Person B disputes any conflict. The current Board of Directors of the national organization has been asked to determine if Person B is eligible for election. Person A, the current president (and person running for re-election) recuses himself from the matter. The rest of the Board makes a determination that Person B is not eligible. In doing so, the Board ignores certain information provided to it by Person B.

Person B appeals the Board’s decision, alleging the Board is biased.

Is this perceived or actual bias and how might you avoid bias in this situation?

This above example was the situation in the SDRCC case of Sharara v. Table Tennis Canada.[15]

The adjudicator clarified that the party alleging bias has the onus of proving the bias and the threshold for finding a real or perceived bias is high. Person B argued that because the members of the Board currently work with Person A and Person A is the only person to benefit should the Board of Directors find Person B ineligible to stand for election, the Board is thus in a conflict of interest between their allegiance to their current colleague and their duties as board members. The adjudicator found that such a relationship would not result in a conflict of interest in every case (otherwise, it would mean that anytime one Board member declared a conflict and recused themselves, the rest of the Board would be in a conflict of interest) but, in this case, the relationship considered in light of the Board’s decision to ignore information brought to its attention by Person B, gives rise to a reasonable apprehension of bias on the part of the Board.

The Right to Assistance

The right to legal counsel is not an absolute legal right. Nonetheless, it is prudent to allow the parties to designate someone to accompany them during the investigation, whether a friend, partner or legal counsel. During the investigation, this person does not speak on behalf of the party, but is there to lend moral support and assist the party in understanding the situation where necessary.[16]

In cases where a party or a witness is under the age of majority in their province or territory of residence, a parent or legal guardian should be informed prior to an interview being conducted and the minor may be accompanied by a responsible adult during the interview.

The Right to a Reasoned Decision

A complainant and respondent have a right to a reasoned decision following an investigation. As noted above, this post-investigative submission would be made by the NIM or sport organization based on the outcome of the investigation. To assist the post-investigation decision-maker a final investigative report should present the findings of the investigation in an impartial and comprehensive manner, documenting the steps taken, the evidence evaluated and ultimately provide the decision-maker with the facts necessary to decide the matter. The report is the means by which the investigator communicates how and why certain findings of fact were made during the investigation, and shows the parties what evidence was considered and that the investigation was done in a fair and transparent manner. Where decisions are based on the findings of the investigation, the parties should have the opportunity to review and respond to the report.

Intersection with Criminal and Child Protection Proceedings

The UCCMS represents a legal regime for addressing maltreatment in sport. As discussed in Chapter 8, this legal regime is contractual, similar to other aspects of the sport system, such as anti-doping rules. This private contractual regime operates in parallel to domestic laws created by government, including Canadian criminal laws and provincial or territorial child protection laws.

The parallel operation of these private and public legal regimes creates interesting dynamics. Historically, sport organizations have sought autonomy to regulate and govern their sports and members free from government control and intervention. Canadian governments have largely accepted the self-regulating status of sport organizations by not making laws to specifically regulate sport organizations or aspects of sport, with some notable exceptions relating to combative sports and concussion safety.[17] While this lack of legislative action can be explained, in part, on Canada’s federal structure and the division of legislative powers between the federal and provincial or territorial governments (see Chapter 6), it also represents governments’ unwillingness to regulate the private affairs of sport.

This does not mean that domestic federal and provincial or territorial laws do not apply to sport. To the contrary, many aspects of sport are regulated by laws of general application that regulate many areas of society, such as those relating to human rights, occupational health and safety, and employment standards. However, despite the general application of these laws to sport, there can still be a tendency to view sport as insulated from or an exception to aspects of these laws.

One example of sport’s insulation or exceptionalism in relation to domestic laws involves doping matters. Doping in sport is primarily regulated by private anti-doping rules. These anti-doping rules are created at the international level by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), and adopted and enforced by international and national sport organizations, including the International Olympic Committee (IOC), international sport federations, and national anti-doping organizations. As private entities within the sport system, WADA and other anti-doping organizations are protective of their autonomy and control over the regulation of doping in sport.[18]

When national governments have attempted to use domestic laws to regulate doping in sport, the IOC and WADA have pushed back on this intervention. For example, during the 2006 Olympics in Turin, Italy, the IOC expressed concern about the application of Italian criminal laws to athletes caught doping and asked the Italian government to suspend its criminal laws for the duration of the Olympic Games. The Italian government refused, but a compromise was reached whereby the IOC was responsible for all doping control testing, and Italian authorities would only conduct searches of athlete residences if acting on “important information”.

In the News:

In the News:

Italy’s Anti-Doping Laws and the 2004 Olympics

“Italy’s Strict Anti-Doping Laws Clash with Olympic Rules” by Tom Goldman, NPR All Things Considered, December 8, 2005 (audio and transcript).

In the lead-up to the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, Italy, a controversy arose regarding the outlook on athlete drug use, and how potential violators were to be punished. In Italy, athletes who took performance-enhancing drugs faced criminal prosecution and possibly even a jail sentence. The IOC’s stance was not as harsh, and officials were pushing to keep jail time out of the picture. When interviewed, some athletes agreed with the IOC, while others felt that by eliminating the Italian laws, the Olympic committee was losing its greatest doping deterrent. How might a compromise be reached in this sort of situation?

More recently, the United States passed the Rodchenkov Anti-Doping Act to, among other things, establish criminal penalties for those who participate in a commercial scheme to influence major international sport competitions through doping. Before the Act was passed and signed into law, then WADA President Witold Bańka issued a public statement cautioning the U.S. Senate about enacting a law that would operate in parallel to global anti-doping rules:

“WADA calls on the US Senate to consider widely held and legitimate concerns about the Rodchenkov Act. The bill in its current form could lead to overlapping laws in different jurisdictions that would compromise having a single set of rules for all athletes, all sports and all anti-doping organizations that are subject to the World Anti-Doping Code. This harmonization of rules is at the very core of the global anti-doping program.”[19]

Maltreatment in sport may be another example of this exceptionalism or autonomy from domestic laws. Although the types of maltreatment defined in the UCCMS are addressed in federal criminal laws (see Table 8.1 below) or provincial or territorial child protection legislation, the sport community has learned that these domestic laws are not sufficient to protect sport participants from maltreatment, and that parallel sport-specific rules (i.e., the UCCMS) are necessary. However, unlike anti-doping rules, the creation of the UCCMS should not deter the reporting and investigation of allegations of maltreatment under parallel domestic laws.

Table 8.1 Overlap Between Definitions of Maltreatment under UCCMS and Offences Under Canadian Criminal Laws[20]

| UCCMS Provision | Criminal Code Provision |

| Psychological Maltreatment – Verbal Acts | Section 372(1): Harassing communications – everyone commits an offence who, without lawful excuse and with intent to harass a person, repeatedly communicates, or causes repeated communications to be made, with them by means of telecommunication. |

| Non-Assaultive Physical Acts | Section 423(1): Intimidation |

| Acts that Deny Attention or Support | Section 219: Criminal Negligence (if respondent owes duty to complainant) |

| Contact Behaviours | Section 265(1): Assault |

| Non-contact Behaviours | Section 219: Criminal Negligence |

| Sexual Maltreatment | Section 271: Sexual Assault Section 153(1): Sexual Exploitation Section 151: Sexual Interference |

| Neglect | Section 219: Criminal Negligence |

| Grooming | Section 153(1): Sexual Exploitation |

| Retaliation | Section 423(1): Intimidation |

The following two sections examine the duty to report allegations of maltreatment to police and child protection authorities, and the possibility of parallel investigations of alleged maltreatment conducted by sport authorities (NIM or ITP), the police, and child protection authorities.

Duty to Report

When an allegation of maltreatment in sport is reported to the NIM, or surfaces during the course of an investigation conducted by the NIM or an ITP, then it is necessary to consider whether there is a duty to report that allegation to authorities outside of sport that might have jurisdiction under domestic laws. In Canada, these relevant authorities are the police (in the case of criminal laws) and child protection authorities (in the case of provincial or territorial child protection laws).

Reporting to Police

There is no explicit duty to report alleged maltreatment to police under Canada’s criminal laws.[21] However, in certain circumstances, a failure to report maltreatment could constitute a criminal offence under Canadian law, especially if combined with other acts or omissions. For example, section 21 of Canada’s Criminal Code provides that a person is a party to a criminal offence if they do or omit to do anything for the purposes of aiding another person to commit the offence. Section 21 also provides that a person is a party to a criminal offence if they abet (i.e. assist or encourage) another person to commit the offence.

As a result, where maltreatment under the UCCMS is also a criminal offence (see Table 8.1 above), then a person who knows about the maltreatment and allows it to continue to happen through their actions or inactions, could be made a party to the offence. This provision is unlikely to apply to a NIM or ITP investigator who is investigating an allegation of maltreatment in sport as they are taking active steps to verify an allegation (as opposed to ignoring it) and may recommend preliminary measures that limit a respondent’s interactions with a complainant and other sport participants pending the outcome of an investigation. However, section 21 of the Criminal Code could apply to sport participants (e.g. coaches, officials, administrators) who suspect maltreatment and take no steps to address or report it.

Although there is no explicit duty to report allegations of maltreatment to the police under Canada’s criminal laws, there may be a duty to report allegations to police (or to recommend to a complainant that they should file a report with police) under a sport organization’s rules. For example, in the McInnis case described above, Athletics Canada’s rules placed a positive obligation on an investigator to advise complainants to report criminal allegations to the police. Similarly, section 2.2.7.1 of the UCCMS requires adult participants who know of or suspect psychological maltreatment, sexual maltreatment, physical maltreatment or neglect involving a minor participant to report that knowledge or suspicion to “law enforcement or child protection services (when applicable).” A person who fails to comply with this duty to report shall be subject to disciplinary action under the UCCMS.

Unfortunately, the reference to “or” and “when applicable” in the above provision creates some ambiguity. It is not clear whether the UCCMS requirement is intended to create a standalone duty to report maltreatment to police and child protection services where the knowledge or a suspicion of maltreatment against a minor exists, or whether the requirement under the UCCMS is only triggered where there is a separate duty to report under other law. If the former interpretation is correct, then it is unclear why the phrase “when applicable” is used. If the latter interpretation is correct, then the provision is still confusing because, as mentioned above, there is no duty to report maltreatment to the police under federal criminal laws. The more likely interpretation is that the phrase is meant to qualify the duty to report to child protection authorities.

As discussed below, the duty to report under provincial or territorial child protection legislation varies by jurisdiction (and in many jurisdictions may not apply to maltreatment in sport). Nevertheless, the reference to “or” suggests that an adult participant could avoid disciplinary action under the UCCMS if they reported maltreatment against a minor participant to either the police or child protection authorities. It is unclear why reporting to both the police and child protection authorities is not required.

It is our recommendation that this section of the UCCMS be revised to clarify its application. Ideally, the UCCMS duty to report should not be limited to instances where the reporting is required under other laws. The duty to report should apply regardless of whether it is required under federal criminal laws or provincial or territorial child protection laws. If the enforcement authority receiving the report is not able to act on the information because it is outside of their jurisdiction (e.g. not a criminal offence), then the reporting errs on the side of caution in favour of preventing and addressing maltreatment in sport.

Reporting to Child Protection Authorities

Every province or territory in Canada has child protection legislation to safeguard children from abuse and neglect. Child protection authorities are given powers under this legislation to conduct investigations and make decisions about child protection and intervention. Despite this apparent breadth, aspects of the legislation and the work of child protection authorities are largely focused on preventing children from abuse and neglect in the home setting.

The existence of a legal duty to report alleged maltreatment to child protection authorities depends on where the alleged maltreatment took place due to different reporting requirements under provincial and territorial child protection legislation (see Table 8.2 below). In British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Yukon and Nunavut, a person’s duty to report maltreatment to child protection authorities is only triggered where the person suspects that the maltreatment is the result of an act or failure to act of a parent or legal guardian, and not third parties (such as athletes, coaches or administrators). As a result, if a person (such as a NIM or ITP investigator, or a sport administrator) has no reason to believe that the maltreatment of a child athlete is linked to an act or failure to act of a parent or guardian, then there would be no duty to report the alleged maltreatment to child protection authorities in these provinces and territories.

Table 8.2 Summary of Duty to Report under Provincial/Territorial (P/T) Child Welfare Legislation

| P/T Jurisdiction | Legislation | Third Party’s Duty to Report Triggered by their Suspicion of an Act or Failure to Act Involving: |

| British Columbia | Child, Family and Community Service Act, RSBC 1996, c 46 | Parent |

| Alberta | Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act, RSA 2000, c C-12 | Legal guardian |

| Saskatchewan | The Child and Family Services Act, SS 1989-90, c C-7.2 | Parent |

| Manitoba | The Child and Family Services Act, C.C.S.M. c. C80 | Person with care, custody, control, or charge of child[22] |

| Ontario | Child, Youth and Family Services Act, 2017, S.O. 2017, c. 14, Sched. 1 | Parent or person with charge of the child |

| Quebec | Youth Protection Act, CQLR c P-34.1 | Parent |

| New Brunswick | Family Services Act, SNB 1980, c F-2.2 | Not associated with any particular person |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | Child and Youth Care and Protection Act, SNL 2010, c C-12.2 | Parent |

| Nova Scotia | Children and Family Services Act, SNS 1990, c 5 | Parent |

| Prince Edward Island | Child Protection Act, RSPEI 1988, c C-5.1 | Parent |

| Yukon | Children’s Act, c 31 | Parent |

| Nunavut | Child and Family Services Act, S.N.W.T. 1997, c 13 | Parent |

In contrast, in Ontario and Manitoba, a person’s duty to report exists if they believe the alleged maltreatment arises from the act or failure to act of a parent or “other person who has care/charge of the child”. This broader description would likely capture coaches and administrators in circumstances where a child athlete is under their care, such as during training practices or at competitions. For example, in the case of R. v. Kates, an Ontario court held that the phrase “person having charge of the child” in Ontario’s Child and Family Services Act (as it was then known) was broad enough to include the employee of a day care who was alleged to have been abusive against children at the day care, thus triggering a duty to report for the operator of the day care who knew about the allegations.

Finally, New Brunswick’s legislation has the broadest duty to report and would apply in the sport context as it is triggered if a child experiences certain forms of maltreatment due to the actions or inactions of any person, and not only a parent, a guardian or a person who has care or charge of a child.

Parallel Investigations

An investigation into sport maltreatment could be commenced by the police, a child protection authority, or both, following their receipt of a complaint or report of alleged maltreatment. However, what happens when such an investigation coincides with a parallel investigation being planned or conducted by the NIM or ITP? Can the different investigations proceed in parallel or should the NIM or ITP investigation be deferred pending the outcome of the police or child protection authority investigation? Is one investigation more important or time-sensitive than the other? Should parallel investigations be avoided to ensure that one investigation doesn’t interfere or conflict with the other?

Some insight into these questions can be obtained from international comparators. In the United Kingdom, it is recommended that investigations into sport maltreatment conducted by sport organizations (or ITPs retained by sport organizations) be deferred until the completion of investigations conducted by statutory enforcement authorities, such as the police and child protection authorities.[23] In contrast, in the United States, an investigation into sport maltreatment conducted by the Center for SafeSport is not automatically impacted by parallel criminal investigations. Instead, the Center may contact the criminal law enforcement agency to discuss the status of their investigation and, at request of the agency, the Center may delay its investigation until the evidence-gathering phase of the criminal investigation has ended.[24] Importantly, the Center does not propose to defer its investigation pending the outcome of criminal charges or proceedings.

It is our recommendation that the NIM (and ITPs) follow the U.S. SafeSport model when investigating alleged maltreatment while parallel investigations conducted by the police or child protection authorities are underway. This recommendation is based on the following three considerations:

- Preserving evidence;

- Enabling timely information sharing; and

- The different standards of proof that might apply.

1. Preserving Evidence

Investigations of alleged maltreatment are likely to involve verbal recollections of events from the complainant, respondent and witnesses that may fade over time. To preserve the freshness of this evidence in order to make findings of fact and fairly assess credibility, it is important that an investigation not be unduly delayed.

2. Enabling Timely Information Sharing

In the sport maltreatment context, both the NIM/ITP and other investigative bodies (police, child protection authority) will bring a certain type of expertise to an investigation. One investigator may be able to obtain information or have particular insight regarding the information they have gathered that another investigator may not, and vice versa. As a result, subject to applicable privacy laws[25] and constitutional limits,[26] parallel investigations can allow investigative bodies to share, in a timely manner, the information that they receive to assist each other’s investigation. For example, the U.S. Center for SafeSport will ask a criminal law enforcement agency whether any information obtained by that agency can be disclosed to the Center to assist with the Center’s investigation, and the Center may, in turn, provide some or all of its case information, documentation or evidence to the law enforcement agency.[27]

3. Standards of Proof

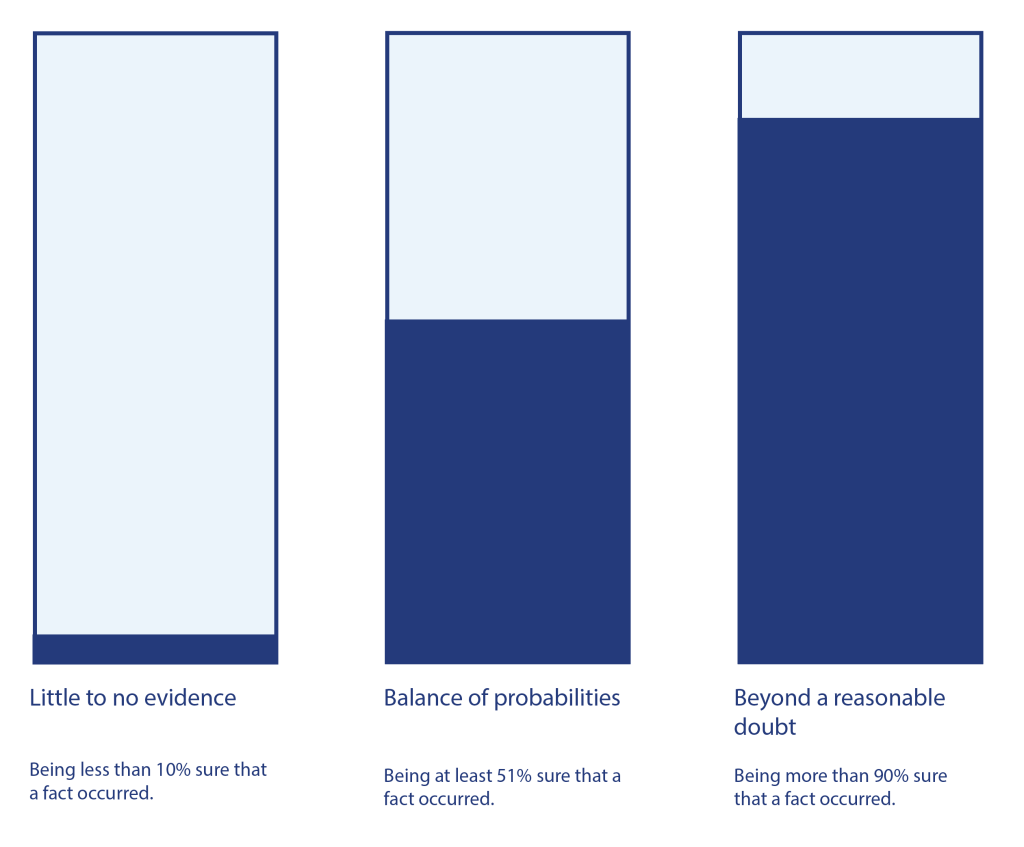

This final consideration relates to a parallel criminal investigation. The purpose of a criminal investigation is to gather evidence to determine whether a criminal offence has been committed. In order for the investigation to lead to a criminal charge and subsequent conviction in court, the evidence gathered must prove that a person committed the criminal offence beyond a reasonable doubt. This threshold is known as a standard of proof. In contrast, in the context of the UCCMS process, the standard of proof will be much lower. The threshold is whether it is more likely than not that a respondent violated the UCCMS (known as a balance of probabilities). Figure 8.3 below provides a visual representation of these standards of proof.

The following figure displays the standards of a “balance of probabilities” and “beyond a reasonable doubt” as partially filled glasses of water. The water represents the evidence supporting the existence of a fact and the unfilled portion represents doubt about the existence of the fact. This doubt can arise due to gaps in the supporting evidence or contradictory evidence.

Figure 8.3 Standards of Proof Illustrated

These different standards of proof impact how an investigation may be conducted since the investigator is considering what threshold needs to be met to prove that a particular fact occurred. For example, while a NIM or ITP investigator may be satisfied that maltreatment occurred based on interviews with a complainant, a respondent and witnesses, a criminal investigator may require supporting documentary or physical evidence before recommending that criminal charges be pursued. This difference in the investigative approach means that there may not be complete overlap between the investigations conducted by the NIM/ITP and the police and that both investigations can proceed in parallel.

The following audio recording is a firsthand dialogue of a person falsely accused of sexual harassment. As you listen, follow along as pieces of the investigation unfold and as the implications of the allegations take hold.

Listen to “The Accusation ” by The Daily on Apple Podcasts (approx. 52 minutes). Find additional material, including a link to the print version in the New York Times, on the episode website.

The difference in standards of proof also means that, if there is a desire to sequence the investigations, as opposed to having them operate in parallel, then the NIM/ITP investigation should not be deferred beyond the evidence-gathering phase of the criminal investigation. Waiting for the outcome of the criminal process (investigation, laying of charges, trial) will not assist the NIM/ITP investigation (or later stages of the UCCMS process) as a finding that no criminal offence was committed (whether following an investigation or trial) is not an indicator that maltreatment in violation of the UCCMS did not occur. In other words, the criminal process does not dictate how the UCCMS process should unfold in terms of findings of maltreatment or consequences for maltreatment.

Case Study:

Case Study:

Review a Harassment Complaint

“Athletics Canada Upholds Lifetime Ban of Ottawa Track Coach” CBC News, July 9, 2020.

As you read through this case, consider the process used to investigate a complaint of harassment made against a coach. The investigation process itself was seriously flawed and the investigator showed bias in the writing of the investigative report. Can you identify the flaws? Do you think the decision was fair?

The Facts

Andy McInnis was a successful coach with the Ottawa Lions Track & Field Club (“OLTFC”). A complaint involving harassment and sexual harassment was filed with the OLTFC against McInnis. The OLTFC hired an investigator to review the complaint. Concerns were subsequently brought forward that the OLTFC was not conducting an impartial investigation and a further complaint of harassment was filed against McInnis by another party (“Eliza”). Athletics Canada assumed responsibility for investigating this second complaint of harassment, appointed an investigator and suspended the OLTFC investigation. The OLTFC investigation was subsequently re-commenced, running in parallel to the one authorized by Athletics Canada.

At the end of the investigation, the Athletics Canada Investigator declared two of the complaints brought by Eliza to be founded and seven of the complaints brought by the original complainant to the OLTFC to be founded. The OLTFC Investigator of the original complaint dismissed all but one of the original complaints as being unfounded on the basis of a lack of evidence. Based on the findings and recommendations of the Athletics Canada Investigator, an Athletics Canada Commissioner rendered a lifetime suspension of McInnis from Athletics Canada.

The Issues

McInnis appealed the Athletics Canada decision. The appeal raised two critical questions:

- Did the investigation and decision-making process follow principles of procedural fairness?

- Was there bias involved in the investigation?

On the question of procedural fairness, McInnis argued that he had not received sufficient information to fully understand the case to be met and to make a full and accurate response, and that the person authorized to make the final decision in the case (the Athletics Canada Commissioner) did not do so, wrongly deferring to the recommendations of the Investigator. Specifically, McInnis maintained that:

-

He had not received details of the specific complaints, including the specific policy sections he was alleged to have breached, and detailed information as required under Athletics Canada’s rules and required by the principles of procedural fairness, all of which were essential for him to make a full response;

-

He was not provided with all of the evidence, including recordings of interviews with the witnesses and complainants; he received only a copy of paraphrased allegations, many of which were out of context;

-

He was not given an opportunity to make his case – either as part of the investigation or as part of a hearing, either in-person or by conference call; and

-

By simply accepting the outcome and recommendations contained in the Investigator’s report, the Athletics Canada Commissioner wrongly delegated his authority to make the final decision to the Investigator and, in so doing, did not fully and fairly consider McInnis’s case in accordance with the principles of fairness but deferred to the Investigator.

On the question of bias, McInnis argued that the Investigator’s report gave rise to a reasonable apprehension of bias on the part of the Investigator that coloured the Commissioner’s final decision. Specifically, he maintained that:

- The Investigator exceeded his authority and mandate and became an advocate for the complaints as evidenced by the inclusion of “victim impact statements”, which were of little probative value to the investigation itself;

- The Investigator used inflammatory and prejudicial language in the report such as the title of the Report – “In Plain View: The Tolerance of Sexual Misconduct at the Ottawa Lions Club,” in subheadings to the report, including: “Emulating the Catholic Church”, “Andy McInnis the Teetotaller”, “Massage Me Not”, “The Womanizer” and “Athletics Canada Ruined the Whole Thing!”, and in a number of highly prejudicial statements;

- The manner of interviewing wherein the original complainant was allowed to read from and refer to a previously written statement;

- The Investigator attempted to discredit and undermine witness evidence given on behalf of McInnis; and

- The investigation conflated, and considered as one, complaints against a third party with those against McInnis.

The Decision

The SDRCC Adjudicator found that McInnis had been denied procedural fairness during the investigation and decision-making phases of the process. He emphasized that while Athletics Canada is entitled to some deference in selecting details of the investigatory process, the serious impact a decision could have on McInnis’s ability to continue with his livelihood demanded a significant degree of procedural protection and a fair process.

The SDRCC Adjudicator found that the right to procedural fairness was not as broad as that argued by McInnis but Athletics Canada failed to provide him with a fair process. The Adjudicator pointed to several errors:

-

The lack of time that McInnis had to review and respond to the Investigator’s report (only 10 days) was unreasonable given the seriousness of the matter and the repercussions of any decision based on the investigative report;

-

While the ultimate decision-maker (in this case the Commissioner of Athletics Canada) had discretion to determine the nature and format of any hearing, such determination must be consistent with the duty of fairness owed to McInnis. In this case, more than the submission of a written statement was necessary. McInnis should have been given the opportunity to test the evidence against him and to question the complaints that were being relied upon to determine his guilt or innocence.

However, the SDRCC Adjudicator rejected a number of the procedural protections sought by McInnis. For example, the Adjudicator noted that an investigation is different than a hearing and what is owed to a respondent in an investigation from a procedural perspective is less formal. The duty of an investigator is to put to the respondent any and all allegations on which the investigator will make findings. Prior to any interview with the investigator, the respondent is not owed details of the allegations relating to the complaints or full reports.

The Adjudicator also concluded that the investigation in this case was conducted in a biased manner. He raised the following points as supporting a finding of actual bias.

-

The use of language in the report was often inflammatory, highly editorial and prejudicial serving no purpose other than to infer McInnis’s guilt;

-

Allegations against McInnis were conflated with those against a third party, treating them as one and the same. Allegations against the third party were separate, not part of the complaint and should not have been brought into the investigation. They properly should have been part of another separate investigation conducted by another investigator;

-

Bringing in commentary and issues outside the scope of the investigation that had the effect of colouring the investigation;

-

Making unsupported findings and completely ignoring facts that contradicted McInnis’s guilt; and

-

Because the final decision made by the Commissioner of Athletics Canada was based solely on the investigative report and did not consider at all the OLTCF’s parallel investigative report that produced contrary findings, the bias of the investigator’s findings and conclusions resulted in a biased post-investigation decision.

As part of his judgment, the SDRCC Adjudicator included a non-exhaustive list of elements characteristic of a good and procedurally fair investigation, including:[28]

- Follow the rules of the governing body to determine whether the complaint must be disclosed to the respondent;

- Ensure that the respondent be made fully aware of the complaint and contents;

- Review and carefully consider all evidence (both inculpatory and exculpatory);

- Interview all witnesses put forward by both sides unless there are compelling reasons not to do so. If an investigator chooses not to interview someone this should be identified in the final report and reasons given for why that decision was made;

- There is not an absolute right to know the names of witnesses or have access to their witness statements, but respondents should be given accurate information of what is being alleged (i.e. place, time and occurrence);

- Allow the respondent to respond to all allegations and/or evidence that will be relevant to the investigation’s findings;

- Allow the complainant to provide further evidence if complaint not founded;

- Allow and consider written submissions disputing findings;

- Give ample time for both the respondent and the complainant to make their cases;

- Provide a final report that is responsive to the original mandate letter and does not go out of its way to answer more than has been set out in the mandate;

- Provide a final report that presents its findings in an impartial manner that is free of hyperbole and editorializing;

- Final investigation reports should be written in a way that the findings against one respondent are separate from unique claims against another where multiple respondents are being investigated on separate issues;

- It is appropriate for investigators to make recommendations regarding policy and procedure and systemic issues, but not to recommend sanctions. It is not the role of the investigator to advocate for an appropriate penalty or sanction. That is the discretion of a post-investigation decision-maker; and

- Carry out an investigation and produce a final report in a timely manner.

Further Research

A concern raised with the US SafeSport[29] model is that it is complaint-based and investigations are limited to the parameters of the complaint. There is often no opportunity to extend an investigation to include aspects of organizational culture and practice. Having regard to abuse-based situations that were allowed to persist for years and even decades (such as Bertrand Charest at Alpine Canada, Larry Nassar at U.S.A. Gymnastics, and Alberto Salazar at the Nike Oregon Project, to name a few), investigations must go beyond the actions of individual respondents and include what goes on within a sport organization to allow situations to fester and go unanswered, and even single instances of abuse to occur.

Can the UCCMS and the NIM be used to address this broader perspective? Is there a better approach? Could the Philadelphia Case Review Model referred to in “In The News” box noted earlier in this chapter be used or modified for such use?

Key Terms

Suggested Assignments

- Read the following checklist of procedural fairness protections articulated by the SDRCC in the case of McInnis v. Athletics Canada and Ottawa Lions Track and Field. Do you disagree with any of the items in the checklist shown below based on what you have learned in this chapter? If so, why? Would you add any items to the checklist shown below?

- Follow the rules of the governing body to determine whether the complaint must be disclosed;

- Ensure that the respondent be made fully aware of the complaint and contents;

- Review and carefully consider all evidence (both inculpatory and exculpatory);

- Interview all witnesses put forward by both sides unless there are compelling reason not to do so. If an investigator chooses not to interview someone this should be identified in the final report and reasons given for why that decision was made;

- There is not an absolute right to know the names of witnesses or have access to their witness statements, but respondents should be given accurate information of what is being alleged (i.e. place, time and occurrence);

- Allow the respondent to respond to all allegations and/or evidence that will be relevant to the investigation’s findings;

- Allow the complainant to provide further evidence if complaint not founded;

- Allow and consider written submissions disputing findings;

- Give ample time for both the respondent and the complainant to make their cases;

- Provide a final report that is responsive to the original mandate letter and does not go out of its way to answer more than has been set out in the mandate;

- Provide a final report that presents its findings in an impartial manner that is free of hyperbole and editorializing;

- Final investigation reports should be written in a way that the findings against one respondent are separate from unique claims against another where multiple respondents are being investigated on separate issues;

- It is appropriate for investigators to make recommendations regarding policy and procedure and systemic issues, but not to recommend sanctions. It is not the role of the investigator to advocate for an appropriate penalty or sanction. That is the discretion of a panel; and

- Carry out an investigation and produce a final report in a timely manner.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 8.1 This graphic demonstrates the pathway of a complaint in the investigative phase. It begins with the intake of a complaint, the formal complaint of maltreatment, and then goes to the National Independent Mechanism (NIM) preliminary assessment. Next comes the investigation, either by the NIM or an Independent Third Party (ITP). Finally, the investigation decision & report is made by either the NIM or the sport organization. [return to text]

Figure 8.3 This graphic illustrates the standards of proof thresholds. On the left, little to no evidence is demonstrated by a rectangular shape shaded in slightly, with the caption “being less than 10% sure that a fact occurred.” The middle rectangle with the balance of probabilities is half shaded in and captioned “being at least 51% sure that a fact occurred.” The last rectangle showing beyond a reasonable doubt is almost fully shaded in, and captioned “being more than 90% sure that a fact occurred.” [return to text]

Sources

Canadian Safe Sport Program. (2020). Sport Information Resource Centre: Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS),(5)1, 1-16. https://sirc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/UCCMS-v5.1-FINAL-Eng.pdf

CBC News. (2020, June 9). Athletics Canada upholds lifetime ban of Ottawa track coach. Retrieved December 21, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/andy-mcinnis-ban-1.5604921

Chamberlain, C., Quinlan, C., & Wernick, S. (n.d.). Practical guide to undertaking safeguarding investigations in sport. Sport Resolutions. http://www.sportresolutions.com/images/uploads/files/2021_NSP_Investigation_Guide_1.pdf

Child and Family Services Act, S.N.W.T. 1997, c 13

Child and Youth Care and Protection Act, SNL 2010, c C-12.2

Child Protection Act, RSPEI 1988, c C-5.1

Child, Family and Community Service Act, RSBC 1996, c 46

Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act, RSA 2000, c C-12

Child, Youth and Family Services Act, 2017, S.O. 2017, c. 14, Sched. 1

Children and Family Services Act, SNS 1990, c 5

Children’s Act, c 31

Combative Sports Act, 2019, S.O. 2019, c. 7, Sched. 9

Family Services Act, SNB 1980, c F-2.2

Goldman, T. (2005, December 8). Italy’s strict anti-doping laws clash with Olympic rules. National Public Radio. Retrieved December 5, 2021, from https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5044688

Legislative Assembly of Ontario. (2018). An act to enact Rowan’s Law (concussion safety), 2018 and to amend the Education Act. https://www.ola.org/sites/default/files/node-files/bill/document/pdf/2018/2018-03/bill—text-41-2-en-b193ra_e.pdf

McInnis v. Athletics Canada, SDRCC (2020), No. 19-0401

McLaren Global Sport Solutions. (2020). Aiming high: Independent approaches to administer The Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport in Canada, final report. http://sirc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/MGSS-Report-on-Independent-Approaches-December-2020.pdf

Paterson v. Skate Canada, (2004), 373 A.R. 81 (QB.)

Pound, R. (2002). The World Anti-Doping Agency: An experiment in international law. International Sports Law Review, 2.

Prime, K. (Producer). (2020, July 26). The Sunday read: ‘The accusation’ [Audio podcast episode]. In The Daily. The New York Times Company. https://podcasts.apple.com/ca/podcast/the-daily/id1200361736?i=1000486163535

R. v. Kates, Ontario District Court – York Judicial District, [1987] O.J. No. 2032.

Rowan’s Law (Concussion Safety), 2018, S.O. 2018, c. 1: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/18r01

Sharara v. Table Tennis Canada, SDRCC (2019), No. 19-0376.

Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC). (2018). Investigation unit: Investigation guidelines. http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/documents/Investigations-Investigation_Guidelines_EN_Final.pdf

Sport Law. (n.d.) Maintaining ‘fairness’ in investigations and hearings. Retrieved December 21, 2021, from https://sportlaw.ca/maintaining-fairness-in-investigations-and-hearings/

Sport Resolutions. (n.d.). https://www.sportresolutions.com

The Child and Family Services Act, C.C.S.M. c. C80The Child and Family Services Act, SS 1989-90, c C-7.2

U. S. Center for SafeSport. (n.d.). SafeSport code. Retrieved December 5, 2021, from https://uscenterforsafesport.org/response-and-resolution/safesport-code/

World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). (n.d.). Retrieved December 21, 2021, from https://www.wada-ama.org

WADA. (2001, May). Coordinating investigations and sharing anti-doping information and evidence. https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/WADA_Investigations_Guidelines_May2011_EN.pdf

WADA. (2020, March 12). WADA calls on US Senate to consider widely held concerns about Rodchenkov Act. Retrieved December 5, 2021, from https://www.wada-ama.org/en/media/news/2020-03/wada-calls-on-us-senate-to-consider-widely-held-concerns-about-rodchenkov-act

Ward, L. & Strashin, J. (2019, February 10). Sex offences against minors: Investigation reveals more than 200 Canadian coaches convicted in last 20 years. CBC News. Retrieved December 21, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/sports/amateur-sports-coaches-sexual-offences-minors-1.5006609

Wilton v. Softball Canada, SDRCC (2004), No. 04-0015.

Women’s Law Project. (2017, August 3).Ottawa police latest to adopt the “Philadelphia Case Review Model” for reviewing unfounded rape cases. Retrieved December 5, 2021, from www.womenslawproject.org/2017/08/03/ottawa-police-latest-to-adopt-the-philadelphia-case-review-model-for-reviewing-unfounded-rape-cases/

Youth Protection Act, CQLR c P-34.1

- McLaren Global Sport Solutions, 2020, p. 50 ↵

- McLaren Global Sport Solutions, 2020, p. 50 ↵

- The UK SafeSport investigation guide considers an investigation to have begun at the point a complaint is received and any action is taken to elicit further information or explore any aspect of concern. (Chamberlain et al., n.d., p. 7) ↵

- McInnis v. Athletics Canada, 2020 ↵

- McInnis v. Athletics Canada, 2020 ↵

- United States Center for SafeSport, n.d. ↵

- SDRCC, 2018; McInnis v. Athletics Canada, 2020 ↵

- SDRCC, 2018 ↵

- McLaren Global Sport Solutions, 2020 ↵

- SDRCC, 2018 ↵

- Investigators are overseen by an advisory committee led by an SDRCC board member unaffiliated with overseeing the arbitration services, and by establishing a clear separation between investigator and the administrative role of SDRCC so as to avoid any interference or apprehension of interference by SDRCC management in an investigation. ↵

- To mitigate this risk of bias, the sport organization could pay another body that retains the investigator (e.g. the NIM or SDRCC), as opposed to directly paying the investigator. ↵

- McInnis v. Athletics Canada, 2020, para. 164 ↵

- Wilton v. Softball Canada, 2004 ↵

- Sharara v. Table Tennis Canada, 2019 ↵

- SDRCC, 2018 ↵

- See, for example, See, for example, Ontario’s Rowan's Law (Concussion Safety), 2018 and Combative Sports Act, 2019 (not yet in force). ↵

- WADA is a private entity at law even though it is partially funded by national governments and includes representatives selected by national governments in its governance structure. This public-private aspect of WADA was proposed by the international sport community at the 1999 World Conference on Doping in Sport following a major doping scandal at the 1998 Tour de France where athletes and support personnel were arrested, detained and charged with criminal offences under French law. The prospect that doping in sport would become regulated by the criminal law and the parallel intervention of national governments into sport that would accompany such regulation was viewed as undesirable by the international sport community: see Pound (2002) ↵

- WADA, 2020 ↵

- Modified from McLaren Global Sport Solutions, 2020, at pages 145-146 ↵

- McLaren Global Sport Solutions, 2020 ↵

- The duty to report under Manitoba’s legislation also triggered where there is a suspicion of harms against a child not associated with any particular person, such as where child is abused, in danger of abuse, or subject to aggression or sexual harassment. ↵

- Chamberlain et al., n.d. ↵

- U.S. Centre for SafeSport, 2021 ↵

- Information obtained by child protection authorities during an investigation may be subject to confidentiality restrictions under provincial or territorial child protection legislation or privacy legislation. ↵

- Generally speaking, police require court orders (e.g. search warrants or production orders) in order to search or seize someone’s private property to avoid violating section 8 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (which protects against unreasonable search or seizure). Physical or documentary evidence obtained through these court orders can be restricted to use in criminal investigations and proceedings, and, if so, could not be used in parallel investigations conducted by other bodies until the information becomes public in a court proceeding. ↵

- U.S. Centre for SafeSport, 2021 ↵

- McInnis v. Athletics Canada, 2020, para. 165 ↵

- United States Centre for Safe Sport, n.d. ↵

Universal Code of Conduct to Address Maltreatment in Sport, promulgated in 2020.

A fact-finding process to determine whether something occurred that involves conducting interviews, asking questions, and collecting documentary evidence.

Sharing of an experience of maltreatment, perhaps to a friend, trusted confidant, sport organization or to a third party; can be distinguished from a formal report.

The process of formally filing a complaint of alleged maltreatment to authorities; can be distinguished from a disclosure.

Independent body charged with overseeing operational aspects of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS). In Canada, the SDRCC has been named as the NIM to oversee the UCCMS. A regulatory body with the authority to implement safe sport policies.

Jurisdiction refers to the territory or sphere of activity over which an organization or individual’s authority extends.

An individual or group that shares no connectedness with the complainant or the defendant.

The individual who reports or files a complaint about another person’s alleged violation of the UCCMS, including an individual who is the subject of alleged maltreatment.

Refers to individual who is alleged to have violated the UCCMS.

The procedures that protect the rights or interests of a complainant or respondent in an investigation.

Principles to ensure that an investigator investigates a matter with an objective and open mind, free from any bias, control or influence.

Showing no prejudice for or against something; impartial.

Often exists where a decision-maker has a direct interest in the outcome or has publicly favoured one outcome over another.

The extent to which the relationship or other factor influences, or is perceived to influence, the decision-maker.

Where a party is involved in multiple interests and serving one of those interests could involve simultaneously working against one of the other interests.

A moral or legal duty to report suspicions of maltreatment to the police or child protection agencies.

Self-Reflection

Self-Reflection