6 Human Rights and Identities in Safe Sport: Considering the Whole Athlete

Themes

Safe Sport policies

Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Accessibility (IDEA)

Learning Objectives

Overview

Marginalized communities have publicly fought for the right to participate in both recreational and high-level sport for the past century. Racialized communities’ ongoing fight against racism in sport began in the early 1900’s with American Jack Johnson’s boxing victory over his white opponent in a white-dominated sport.[1] Canadian women have been working towards equitable sport participation since the late nineteenth century through community movements as small, yet pivotal, as riding a bicycle.[2] 2SLGBTQIA+ athletes have also participated in sport since their conception, fighting for visibility and safety in sport as of 1966 when the International Olympic Committee began mandating sex-based testing for women’s events, targeting and outing intersex women.[3] Advocacy for disabled athletes’ participation in sport began in the post-World War 2 era, with recent evolutions to include meaningful and equitable participation.[4] The impact of these movements are still felt today, paving the way for modern forms of activism to ensure sport is a safe space for all.

Within more recent years, global movements across a variety of sports have worked to generate awareness surrounding the impact of societal discrimination towards athletes. Contemporary methods of activism through media campaigns, including BBC’s “#changethegame”, the Union of European Football Association’s (UEFA) “Equal Game”, and Nike’s “EQUALITY”, inform the public of discrimination that occurs within sport. Although some aspects of the above campaigns include sizable donations to grassroots organizations, rarely do they include concrete, holistic initiatives to ensure athletes of all levels from diverse backgrounds have equitable access to Safe Sport participation.

Effects of sexism, racism, ableism, and homophobia remain abundant in far too many sporting spaces.[5] Approaches to growing Safe Sport initiatives in sporting organizations have taken similarly siloed approaches with a focus on singular identities (race, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, ability) rather than the athlete as an intersectional being operating in multiple systems of power.[6] As such, this chapter posits that for sporting organizations to fully embrace cultures of equity and inclusion, they must apply human rights and intersectional lenses to Safe Sport frameworks.

Key Dates

Safe Sport in North America

The term “Safe Sport” commonly refers to a policy which safeguards athletes and protects them from maltreatment in sporting spaces while optimizing the sport experience for all those involved.[7] Despite the presence of a generally universal understanding of Safe Sport, the creation of Safe Sport policies and the definition of Safe Sport is often left up to the discretion of National Sport Organizations (NSOs). In Canada, for example, large-scale Canadian sport organizations came together in 2019 to create a Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS). This joint initiative brought together a code of conduct to serve as a guideline for Safe Sport policies and practices regarding maltreatment in general. Further, coaches and leaders are directed to engage in Safe Sport training. However, the application of said training and the UCCMS changes depending on the NSO’s policy and implementation.

As another example, the United States’ approach to Safe Sport is done through their U.S. Centre for Safe Sport. Their Safe Sport interventions operate under an independent non-profit organization, separate from NSOs, who developed a centralized Safe Sport Code that applies to all participants involved in Olympic and Paralympic teams. This centre is in charge of receiving complaints, guiding the reporting process, creating training, and developing and updating the Safe Sport Code. Similar to the Canadian context, this organization has little jurisdiction over how sporting agencies adhere to and implement Safe Sport practices. Therefore, a centralized approach to implementing Safe Sport practices at the ground-level is lacking in two major sporting bodies: Sport Canada and the U.S. Centre for Safe Sport.[8]

Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion in Safe Sport

The history of sports exists as a separate, albeit fascinating, field. However, it is impossible to interrogate the current move to Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Accessibility (IDEA) without reviewing the origins.

The origins of organized sport are commonly held to begin with the ancient Greek Olympiad in 776 BCE. However, there is a growing historical record pointing to team sports around the world prior to the first century. Most ancient sports featured only men, although there is some evidence of women’s participation in separate games in ancient Greece. On Turtle Island, now Canada, what we now know as lacrosse has a long history of spirituality, fitness, and resolving conflict.

In most of these instances, sport was a means of promoting a social good, although moving into the era of colonialism, sports have been implicated in establishing and securing patterns of social inequality and marginalization. Indeed, sport played an active role in many colonial practices, civilizing missions, and processes of empire-building. By the turn of the twentieth century, missionary coaches or teachers, driven by political, ideological, and commercial motives, had taken sports to virtually every corner of the non-European world.[9]

In the News:

“We Play to Please the Creator”

“We Play to Please the Creator” by Chris Swezey, Washington Post, July 20, 1998.

“The Iroquois called the game “tewaarathon,” meaning “little brother of war,'” Peter Lund wrote in “The History of the Game of Lacrosse: From the American Indians to the Present.” “They used the sport to keep their warriors in shape, to settle disputes between tribes and as a spiritual exercise to amuse and please the Creator, believed to be the god-like figure Deganawidah who, according to Iroquois legend, united the Six Nations of the Iroquois.”

“Sport: A Tool of Colonial Control for the British Empire” by Isobel Roser, Butler Scholarly Journal, April 30, 2016.

“Sport did not have a singular role in [the British] Empire, it had multiple purposes which changed and developed over time. Sport was used to create bonds, enforce British control and “civilise” the natives. Much like a pushy parent, the motherland tried to encourage her colonies to take up as many sports as possible. Ironically, the British failed to recognise that by bestowing her sports upon the Empire she was empowering her colonies, rather than suppressing them. However, initially, it was a successful imperial tactic, allowing the British a subtle, yet potent means of cultural control.”

When the modern Olympic Games began in 1896, women were not allowed to compete. In 1900, twelve female competitors were permitted to compete in tennis or golf. Through much of history, there was little interest in developing any form of equity in sport – indeed there was no need to do so. People around the world participated in casually organized sports in their villages. The emphasis of sport and strength holding masculine qualities came from a late nineteenth century push in Europe to eradicate what was seen as growing sensitivity amongst men, with compulsory sport woven into educational programmes.[10] Sportsmen became symbols of strength and national pride comparable to military warriors, leading a form of celebrity which their female counterparts were unable to replicate. The sculpting of a sportsperson’s image has traditionally been masculine. Thus, while sport has the ability to promote societal good, sport has also been a contributor to social inequality through centuries of rules and practices that restrict access to participation for certain populations.

The earliest attempts to address inequalities often focus on bringing in individuals who were missing. This brings in people who may be different in terms of race, ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation and other identities but does little to ensure they feel comfortable in the environment. Equity is juxtaposed against equality. Early efforts to ensure equality provided the same standards for everyone without making allowances for individual differences. A phrase commonly thrown around among IDEA professionals is “Diversity is a fact and Inclusion is an act/choice.” Creating an inclusive environment will only happen with intentional action. Accessibility within sport is a move to ensure the greatest number of individuals can participate in the most effective way possible.

An obvious example is Title IX in the United States, passed as part of the Education Amendments of 1972, which banned sex discrimination in federally funded education programs. While the protections were wide-ranging and included gender and sexual violence committed in institutions that received federal funds, it is best known for its impact on expanding opportunities for women and girls in sports. Prior to the implementation of Title IX, female athletes received two percent of college athletic budgets, with virtually no athletic scholarships. Today, more than 100,000 women participate in intercollegiate athletics, a four-fold increase from 1971. That same year 300,000 women (7.5%) were high school athletes; in 1996, that figure had increased to 2.4 million (39%).[11]

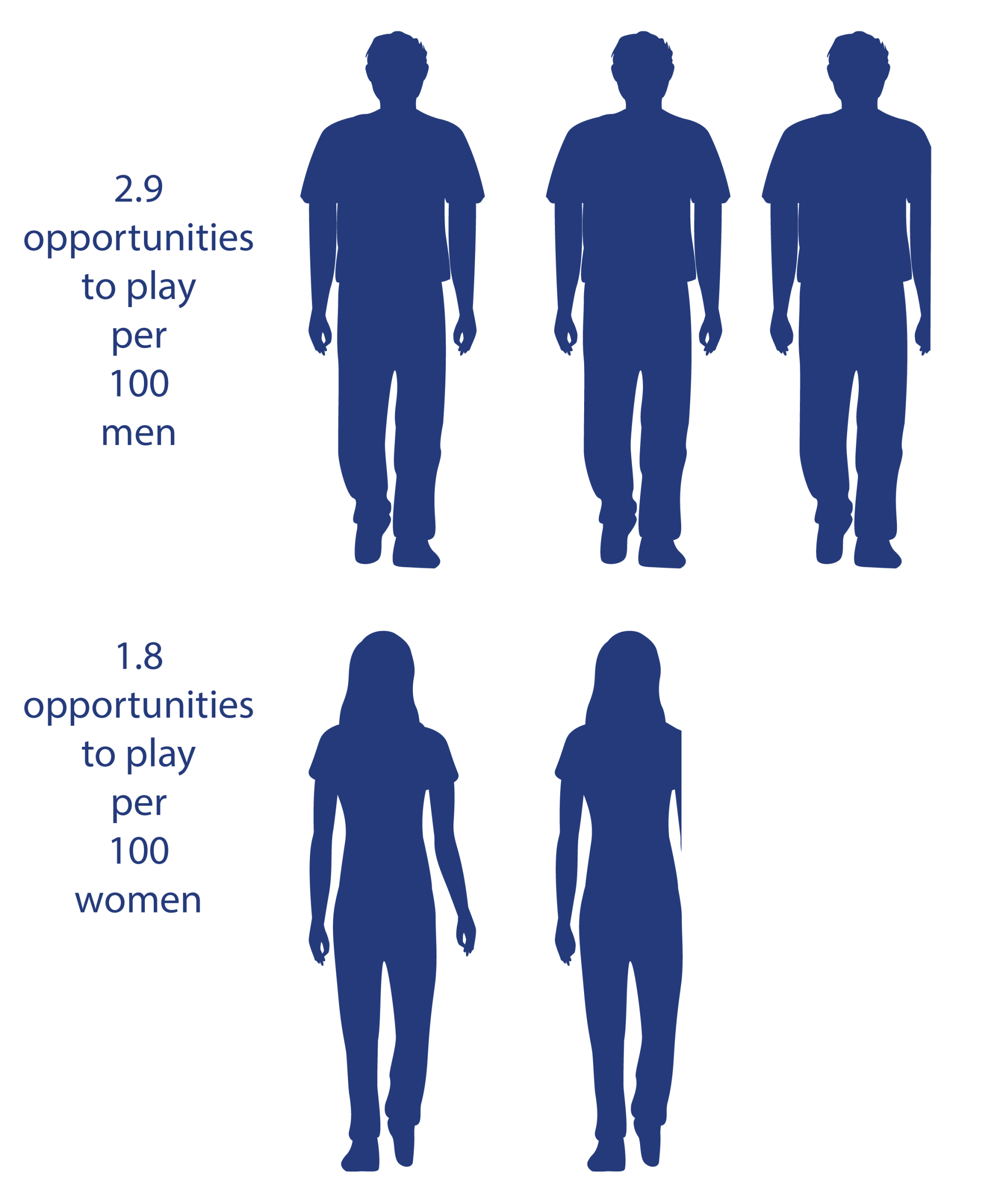

However, that startling change in participation rates does not mean equity exists for female athletes in either the United States or Canada. Once regulations laid out exactly how Title IX would work, one of the central ideas in athletics was that opportunities should fall roughly in line with enrolment. Women now make up about 58% of undergraduates but get just 43% of roster spots and 46% of Division I scholarship money. Researchers at the University of Toronto found much the same in Canada. For every 100 men in Canadian universities, there are 2.9 chances to play a sport. For every 100 women, there are just 1.8 chances.

Figure 6.1 Opportunities to Play for University Men and Women

Canadian Interuniversity Sport data shows that an identical proportion—40%—of male and female athletes received scholarships last year. However, men got 6.7 million dollars while the women only received 4.8 million dollars. Given that the enrolment rate is higher for females than males, females should represent more than half of student athletes and receive more than half of the scholarship funds distributed. However, current statistics indicate that scholarship funding is not even reporting a 50:50 split between men and women.[12]

The primary lens through which we view accessibility is that of disability. When we discuss accessibility of sports, we must think holistically. When does socioeconomic status impede participation in certain sports? When does geography make it difficult to participate in some sports? Disability in sport did not exist to a significant degree until Dr. Ludwig Guttmann created a competition for war veterans with spinal injuries in 1948. Guttman led a Spinal Injuries Centre in England which was known for its progressive rehabilitation programmes, including introducing competition and sportsmanship back into patients’ lives.

The debut games – named the Stoke Mandeville Games, after the hospital facility they were in – was timed to coincide with the 1948 London Olympic Games to encourage morale and competitive spirit. Holland recognised Guttman’s successful rehabilitation work for veterans and joined the Games in 1952. Today, we recognize this movement as the first Paralympics. The Olympic-based format of the competition and official recognition as part of the Games did not occur until Rome 1960 when four hundred athletes competed and were dubbed with the official Paralympic title in Tokyo 1964.[13]

Furthering Sport and Human Rights

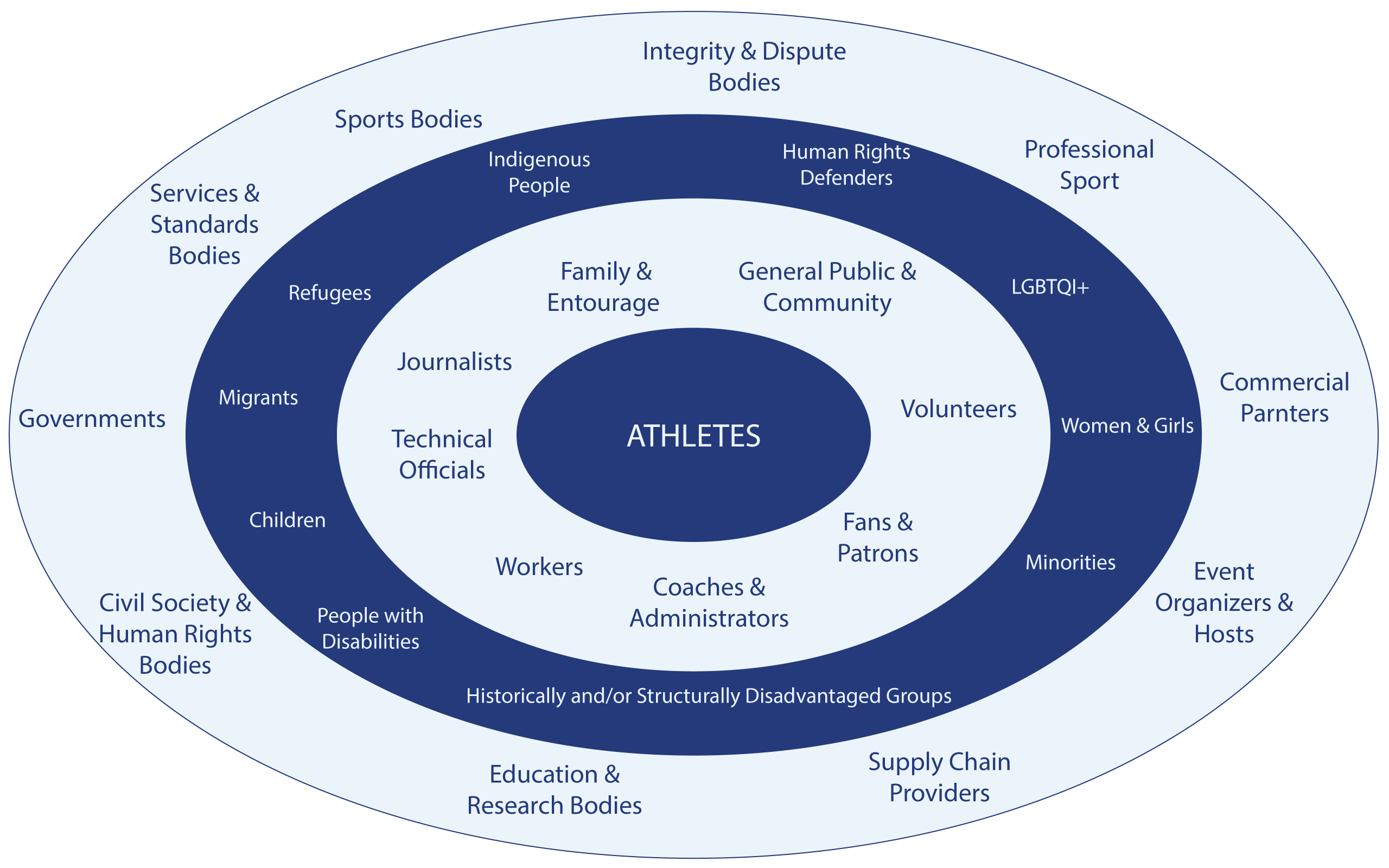

The Centre for Sport and Human Rights (CSHR) serves as a human rights organisation for the world of sport. The CSHR notes that the foundational principles of the world’s preeminent sport bodies speak to universal humanitarian values, harmony among nations, solidarity and fair play, the preservation of human dignity, and commitment to non-discrimination. In Convergence 2025, the strategic plan released by CSHR in September 2021, a sports ecosystem model is used to examine power differentials in sport.

“Power dynamics in traditional sports structures can exacerbate human rights risks to athletes and others. Reimagining sport from a holistic people-centred perspective is an important way to address these concerns. By applying a human rights lens to the ecosystem of sport, an arena that represents an intricate web of symbiotic relationships is revealed encompassing those affected and between different groups of institutional actors (see Figure 6.2). A rights-focused ecosystem model with people at the centre, shows that each of these interactions between all stakeholder groups may impact – positively or negatively – different individuals and communities, through the direct and indirect roles they play.”[14]

Figure 6.2 Sport Ecosystem

Sport’s Alignment with International Human Rights

The Centre for Sport and Human Rights (CSHR) lists ten “Sporting Chance Principles” which affirm a shared commitment to realizing human rights in and through sport. These principles include:

- Sport has inherent power to create positive change;

- Internationally recognized human rights apply;

- All actors involved in sport commit to internationally recognized human rights;

- Human rights are considered at all times;

- Affected groups have a voice in decision-making;

- Access to remedy is available;

- Lessons are captured and shared;

- Stakeholder human rights capacity is strengthened;

- Collective action is harnessed to realize human rights; and

- Bidding to host mega-sporting events is open to all.

Sport cannot exist separate from the world of politics as international human rights, standards, policies, and procedures transcend sport governance at every level. This has been demonstrated on many occasions including Olympic Games boycotts, Jesse Owens’ participation in the 1936 Berlin Games, and the definitions of “male” and “female” applied on the world stage.

We have recently seen how the activism of a lone athlete taking a stance can influence human rights issues on a global scale. National Football League quarterback Colin Kaepernick refused to stand during the United States national anthem in protest of systemic racism within the United States in 2016. While Kaepernick’s activism made him a persona non grata for the NFL, his actions (along with the repercussions felt around the world from George Floyd’s murder in May 2020) have led to players taking knees, wearing armbands, and holding moments of silence that speak to the impact of racism at a global level in sport.

However, despite this acknowledgement and understanding of human rights, there are still cases that provoke controversy and outrage at the international level. In March 2019, the International Association of Athletics Federation (IAAF) was criticized by the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) over concerns that their “discriminatory regulations […] to medically reduce blood testosterone levels contravene international human rights […] including the right to equality and non-discrimination…and full respect for the dignity, bodily integrity and bodily autonomy of the person.”

With specific reference to the IAAF’s Differences of Sexual Development Regulations, the UNHRC called upon states to “ensure that sporting associations […] refrain from developing and enforcing policies […] that force, coerce or otherwise pressure […] athletes into undergoing unnecessary, humiliating and harmful medical procedures”. A 2020 Human Rights Watch report noted that testosterone regulations are humiliating for the athlete, medically unnecessary and lead to human rights violations. Some of the violations outlined in the report include: physical and psychological injury, career loss based on discrimination, coerced medical intervention, and a violation of fundamental rights to health, privacy and dignity. Testosterone regulation also reinforces racially biased and Western standards of femininity, leading to the disproportionate discrimination of women of colour from Africa, Oceania, Asia, and Latin America.[16]

Highly publicized cases of this rule restricting athletes from participation include South Africa’s Caster Semaya, as well as Namibian 2020 Olympic medal contenders Christine Mboma and Beatrice Masilingi who were pulled from the 400m due to their high testosterone levels and forced to compete in the 200m event. As CBC Sports’ commentator Morgan Campbell wrote,

“Except there’s a qualitative difference between anabolic steroids and naturally produced testosterone. Mboma’s and Masilingi’s default hormonal settings are no more an unfair advantage than Kawhi Leonard’s giant hands, or keen eyes in Major League Baseball, where the average player sees with 20/13 vision. If you can picture MLB forcing left-handers with 100 mph heat and 20/10 vision to play first base, arguing their natural tools were unfair to regular players, then you can understand how arbitrary, targeted unfairness of World Athletics’ testosterone guidelines.”[17]

The Swiss-based Court for the Arbitration of Sport ruled that forcing or coercing athletes to undergo unnecessary medical treatment is discriminatory. The panel found that the DSD Regulations are discriminatory, but the majority of the panel found that, on the basis of the evidence submitted by the parties, such discrimination is a necessary, reasonable and proportionate means of achieving the IAAF’s aim of preserving the integrity of female athletics in the restricted events.

In the News:

Human Rights on the Olympic Stage

“When Should Countries Boycott the Olympics,” by Sergei Guriev, New York Times Opinion Pages, February 6, 2014.

“2-time Olympic snowboarder calls for Team Canada boycott of Beijing 2022,” by Karin Larsen, CBC News, December 19, 2021.

“China warns nations will ‘pay price’ for Olympic boycott” BBC News, December 9, 2021.

There have been Olympic Games boycotts in 1936, 1956, 1964, 1972, 1980, and 1984. The geopolitics of the twenty-first century has brought about debate prior to almost all recent Olympic Games. [18]

“Jesse Owens Biography” Olympics.com

Jesse Owens travelled to Berlin to take part in the 1936 Olympics – an event overseen by Adolf Hitler, which the new German chancellor hoped would profile the supremacy of the Aryan “master race”. It wasn’t to be. The African-American Owens stole the show. He won the 100m in 10.30 seconds, the 200m in 20.70 seconds, and then the long jump, with an impressive leap of 8.06 metres – apparently after getting some advice about his run-up from a German competitor, Luz Long. His fourth gold came in the 4x100m relay, in which Owens formed a key part of the team that set a new world record of 39.80 seconds.

“IOC transgender guidelines delayed again to 2022 due to ‘conflicting opinions‘” by Michael Houston, Inside the Games, September 21, 2021.

There has been much controversy from the International Olympic Committee on protecting and promoting the human rights of transgender and intersex athletes in competition.

Why IDEA Isn’t Enough – Ways Forward

Leadership

In the world of Olympic sport, women of all ethnic and cultural backgrounds are still finding it difficult to make headway in positions of leadership. The latest Association of Summer Olympic International Federations (ASOIF) Review of International Federation Governance discovered that only one international sports federation had a board that was more than 40% female, while 18 IFs had a proportion of less than 25%. Indeed, when analyzing ten indicators related to international federation integrity, “appropriate gender balance in executive board or equivalent” achieved the lowest mean score, meaning international sport governing boards remain disproportionately male.

Employment practices associated with the sports industry, such as internal hiring practices, are one of the top barriers preventing diversity in the workplace.[19] To change this, people working in sport must “interrogate” how they got there and either change the norm or forcefully create networks that are more inclusive. Changing the internship system, in which eager students work for a big league or franchise for no salary (usually in a city that is expensive to reside in) would be a good start to create opportunities for marginalized students.

Figure 6.3 IDEA: Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility[20]

Cultural Shift

Sports organizations at every level must take seriously the policies that have been put in place to progress IDEA within the domain. Some of these shifts will be difficult, requiring changes in languages, attitudes, and character. There must be a full understanding of why everyone will benefit when the most marginalized in society are fully included.

Listening to Athlete Voices

A pivotal shift sport organizers, managers, coaches, and athletes can also apply to their sporting practice is listening attentively to the voices and opinions of athletes. Integrating the voices of those who are experiencing maltreatment is critical to ending its presence. Furthermore, allowing athletes to have a voice promotes a safe space and encourages athletes to remain involved in sport. We recommend taking an intersectional, trauma and violence informed care (TVIC) approach to integrating Safe Sport practices into sport programs. TVIC considers the multiple identities and oppressions that affect athlete participation, along with potential trauma or violence that athletes have experienced as a result of that oppression.

This could be as simple as listening to athlete voices when creating codes of conduct, policies, educational materials, practice schedules, building layouts and facilities, and marketing materials. Additionally, intersectional and TVIC approaches align with Gurgis and Kerr’s (2021) recommendation that Safe Sport practices promote human rights and advance both athlete and sport development without leaving those who are marginalized behind. These strategies are also meant to promote inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility in sporting spaces, while keeping the rights of the athlete as its centre focus.

Figure 6.4 Chapter Review

Key Terms

Suggested Assignments

- There has been both qualitative and quantitative reporting showing that many women’s teams are coached by men. With a greater spotlight on equity in sports, why is this happening? Choose a sport in which your country competes internationally and examine the coaching staff for the women’s team? What percentage of coaches are female? Are women in head coaching roles?

- Examine your university’s athletics funding by sex and sport. Is there equality? Is there equity? Which sports are best funded? Who plays those sports? Is there more information about equity that can be extrapolated from the data you have found?

Figure Descriptions

Figure 6.2 This figure shows the sport ecosystem, with contents adapted from the Centre for Sport and Human Rights. In the centre of the ecosystem are athletes. In the field surrounding athletes are coaches & administrators, fans & patrons, volunteers, the general public & community, family & entourage, journalists, technical officials, and workers. The third level includes children, migrants, refugees, Indigenous people, human rights defenders, LGBTQ+, women & girls, minorities, people with disabilities, and historically and/or structurally disadvantaged groups. The final level of the ecosystem includes supply chain providers, education & research bodies, civil society & human rights bodies, governments, services & standards bodies, sports bodies, integrity & dispute bodies, professional sport, commercial partners, event organizers & hosts. [return to text]

Figure 6.3 This interactive feature demonstrates the concept of IDEA, or inclusivity, diversity, equity, and accessibility. Inclusion is ensuring all individuals are equally supported, valued, and respected. This is best achieved by creating a research environment in which all individuals (students, faculty, staff, and visitors) feel welcomed, safe, respected, valued, and are supported to enable full participation and contribution. An inclusive and welcoming research culture embraces differences of opinions and perspectives while fostering a learning ecosystem underpinned by respect by all and for all. Diversity is the wide range of attributes within an individual, group, or community that makes them distinctive. Dimensions of diversity consider that each person is unique and recognizes individual differences including ethnic or national origin, gender, gender identity, and gender expression, sexual orientation, background (socio-economic status, immigration status or class), religion or belief (including absence of), civil or marital status, family and caretaker obligations (i.e., pregnancy, elderly), age, and disability. Equity is the fair treatment and access to equal opportunity (justice) that allows the unlocking of one’s potential, leading to the further advancement of all peoples. The pursuit of equity is about the identification and removal of barriers to ensure the full participation of all people and groups. Accessibility is the provision of flexibility to accommodate needs and preferences, and refers to the design of products, devices, services, or environments for people who experience disabilities. “We can look at this as a set of solutions that empower the greatest number of people to participate in the activities in question in the most effective ways possible.” [return to text]

Sources

Abbatine, T., Laby, D. M., & Kirschen, D. G. (2019, August 8). Scope and rope: A visual profile of Major League hitters. Baseball America. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.baseballamerica.com/stories/scope-and-rope-a-visual-profile-of-major-league-hitters/#:~:text=The%20average%20visual%20acuity%20of,results%20on%20the%20general%20population.

Baker, J. & Vasseur, L. (2021, September). Inclusion, diversity, equity & accessibility (IDEA): Good practices for researchers. Canadian Commission for UNESCO. Ottawa: Canada. https://brocku.ca/unesco-chair/wp-content/uploads/sites/122/ToolkitIDEA.pdf

BBC News. (December 9). China warns nations will ‘pay price’ for Olympic boycott. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-59592347

Bradbury, S., & Conricode, D. (2020). Game changer or empty promise?. In S. Bradbury, J. Lusted & J. Sterkenburg (Eds.), ‘Race’, ethnicity and racism in sports coaching (pp. 211-232). Routledge.

Campbell, B. (2021, July 7). Rules governing Olympic runners send a disturbing message to female athletes, especially those who are Black. CBC Sports. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/sports/opinion-case-of-namibian-runners-further-exposes-half-baked-testosterone-regulation-1.6092033

Caudwell, J., & McGee, D. (2018). From promotion to protection: Human rights and events, leisure and sport. Leisure Studies, 37(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2017.1420814

Centre for Sport & Human Rights. (n.d.a). Convergence 2025: Strategic plan (2021-2025). https://sporthumanrights.org/media/os5fx2z0/cshr_convergence_2025.pdf

Centre for Sport & Human Rights. (n.d.b). About us. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.sporthumanrights.org/about-us

Centre for Sport & Human Rights. (n.d.c). Sporting chance principles. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.sporthumanrights.org/about-us/principles/

Colin Kaepernick. (n.d.). Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://kaepernick7.com

Cooper, J. N., Macaulay, C., & Rodriguez, S. H. (2019). Race and resistance: A typology of African American sport activism. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(2), 151–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217718170

Deutsche Welle (DW). (2020, February 20). Racism expert Gerd Wagner: The precedent of abandoning a match needs to be set. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.dw.com/en/racism-expert-gerd-wagner-the-precedent-of-abandoning-a-match-needs-to-be-set/a-52434651

Deutsche Welle (DW). (2021, December 19). German professional football match abandoned due to racist abuse. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.dw.com/en/german-professional-football-match-abandoned-due-to-racist-abuse/a-60187659

Gurgis, J. J., & Kerr, G. A. (2021). Sport administrators’ perspectives on advancing safe sport. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 630071. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.630071

Guriev, S. (2014, February 6). There are more effective ways to bring about change in Russia. The New York Times. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2014/02/06/when-should-countries-boycott-the-olympics/there-are-more-effective-ways-to-bring-about-change-in-russia

Hall, M. A. (2002). The girl and the game: A history of women’s sport in Canada. Broadview Press.

Houston, M. (2021, September 21). IOC transgender guidelines delayed again to 2022 due to “conflicting options”. Inside the Games. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.insidethegames.biz/articles/1113268/ioc-transgender-guidelines-delay-2022

Human Rights Watch. (December 4, 2020). “They’re chasing us away from sport.” Retrieved January 7, 2022. https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/12/04/theyre-chasing-us-away-sport/human-rights-violations-sex-testing-elite-women

International Olympic Committee. (IOC). (n.d.). Jesse Owens. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://olympics.com/en/athletes/jesse-owens

International Paralympic Committee. (n.d.). Paralympics History. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.paralympic.org/ipc/history

Kerr, R., & Kerr, G. (2020). Promoting athlete welfare: A proposal for an international surveillance system. Sport Management Review, 23(1), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.05.005

Kidd, B. (2011). Cautions, questions and opportunities in sport for development and peace. Third World Quarterly, 32(3), 603–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2011.573948

Larsen, K. (2021, December 19). 2-time Olympic snowboarder calls for Team Canada boycott of Beijing 2022. CBC News. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/2-time-olympic-snowboarder-calls-for-team-canada-boycott-of-beijing-2022-1.6287991

MenEngage (2014). Brief on sports and the making of men. http://menengage.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Advocacy-Brief-Sport.pdf

National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education (NCWGE). (2012b). Title IX at 40: Working to ensure gender equity in education. Washington, DC: NCWGE. https://www.ncwge.org/PDF/TitleIXat40.pdf

Pieper, L. (2016). Introduction. In sex testing: Gender policing in women’s sport. University of Illinois Press.

Roser, I. (2016, April 30). Sport: A tool of colonial control for the British empire. The Butler Scholarly Journal. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://butlerscholarlyjournal.com/2016/04/30/sport-a-tool-of-colonial-control-for-the-british-empire/

Rowbottom, M. (2021, October 1). Convergence 2025 strategy launched by Centre for Sport and Human Rights. Inside the Games. Retrieved October 31, 2021, from https://www.insidethegames.biz/articles/1113662/centre-for-sport-and-human-rights-plan

Savulescu, J. (2019, May 9). Ten ethical flaws in the Caster Semenya decision on intersex in sport. The Conversation. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://theconversation.com/ten-ethical-flaws-in-the-caster-semenya-decision-on-intersex-in-sport-116448

Smith, B., & Sparkes, A. C. (2019). Disability, sport, and physical activity. In N. Watson & S. Vehmas (Eds.), Routledge handbook of disability studies (pp. 391–403).

Sportsnet. (2012, June 19). SN magazine: Women still on the sidelines. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.sportsnet.ca/magazine/title-ix-women-still-on-the-sidelines/

Studio Republic. (2020, January 2). A brief history of social inclusivity in sports. Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://www.studiorepublic.com/blog/brief-history-of-social-inclusivity-in-sports

Swezey, C. (1998, July 20). ‘We play to please the creator’. The Washington Post. Retrieved October 31, 2021, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1998/07/20/we-play-to-please-the-creator/7f2b7fe8-8bcc-448c-a1c5-a92b41dfe9ce/

U.S. Center for Safe Sport. (n.d.). Retrieved December 31, 2021, from https://uscenterforsafesport.org

Young, C. (2008). Olympic boycotts: Always tricky. Dissent (00123846), 55(3), 67–72. https://doi-org.proxy.library.brocku.ca/10.1353/dss.2008.0063

- Cooper et al., 2019 ↵

- Hall, 2002 ↵

- Pieper, 2016 ↵

- Smith & Sparkes, 2019 ↵

- Caudwell & McGee, 2018 ↵

- Kerr & Kerr, 2020 ↵

- Gurgis & Kerr, 2021 ↵

- Kerr & Kerr, 2020 ↵

- Kidd, 2011 ↵

- MenEngage, 2014 ↵

- NCWGE, 2012b ↵

- Sportsnet, 2019 ↵

- Studio Republic, 2020 ↵

- Centre for Sport & Human Rights, n.d.a, p. 14) ↵

- Centre for Sport & Human Rights, n.d.b ↵

- Human Rights Watch, 2020. ↵

- Campbell, 2021 ↵

- Young, 2008 ↵

- Bradbury & Conricode, 2020 ↵

- Safe Sport definition from Gurgis & Kerr, 2021. ↵

A collective responsibility to create, foster and preserve sport environments that ensure positive, healthy, and fulfilling experiences for all individuals. A safe sport environment is one in which all sport stakeholders recognize, and report acts of maltreatment and prioritize the welfare, safety and rights of every individual.

Supporting, valuing, and respecting all individuals equally.

The array of attributes that vary between individuals, groups or communities that makes them distinctive.

Fair treatment and access to equal opportunity by removing barriers to ensure full participation.

Flexible accommodations of needs and preferences.

Listening to those involved in sport by asking their opinions and preferences while considering their rights as humans.

Self-Reflection

Self-Reflection