23 Epilogue

Isaiah Clelland

Safe Sport to Safeguarding: A Great Way Forward

Previously in this edited book, Michele Donnelly noted the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS) was an important step toward safe sport in Canada. The UCCMS represented a culmination of years of research that identified the common forms of maltreatment. Moreover, the UCCMS was a major step in meeting the Government of Canada’s 2019 Red Deer Declaration—For the Prevention of Harassment, Abuse and Discrimination in Sport to remove all forms of maltreatment in sport.[1] To reduce the power dynamics of reporting, a third-party service enforced the implementation of the UCCMS.

As of April 1, 2025, the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES), through the new Canadian Safe Sport Program, assumed enforcement of the UCCMS from the Office of the Sport Integrity Commissioner (OSIC). Only national sport organizations (NSOs) fall under the CCES’s jurisdiction, while provincial and community sport organizations—who engage with a majority of sport participants—are left to navigate safe sport on their own. As a closing reflection, this epilogue will explore youth sport at the community level, describing the current environment of safe sport and what safeguarding could look like in the future.

What does safe sport look like at the community level where most participants are?

National data from the Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute (CFLRI) demonstrates that 68% of children (aged 5-17) participate in sport, either through school or community-based programs.[2] If these children are not on a national team, they are not protected by the CCES’s enforcement. Children need a proper safety system.

While not at the elite levels of competition where winning could be a higher priority, community sport maintains a high prevalence of maltreatment. Parent and Vaillancourt-Morel found that 84.5% of Canadian youth aged 14-17 in sport experienced at least one form of violence in sport (81% psychological abuse, 40% physical abuse, and 27% sexual abuse).[3] This finding aligns with recent Australian statistics that 82% of youth in sport (aged 5-17) experience at least one form of violence.[4]

To combat maltreatment, provincial and territorial sport organizations (PTSOs) often align with the definition of safe sport—an environment free from maltreatment—but rely on different enforcement bodies. In Ontario, sport organizations use a combination of independent and direct reporting systems. For example, the Ontario Hockey Federation reports to sportcomplaints.ca (Third Party), Lacrosse Ontario reports to Lacrosse Ontario, Basketball Ontario reports to Basketball Ontario, Ontario Soccer reports to ALIAS Solutions (Third Party), and Swim Ontario reports to the Swim Ontario Dispute Resolution Officer. The result is a convoluted reporting system that does not align from the local sport level to the national sport level.

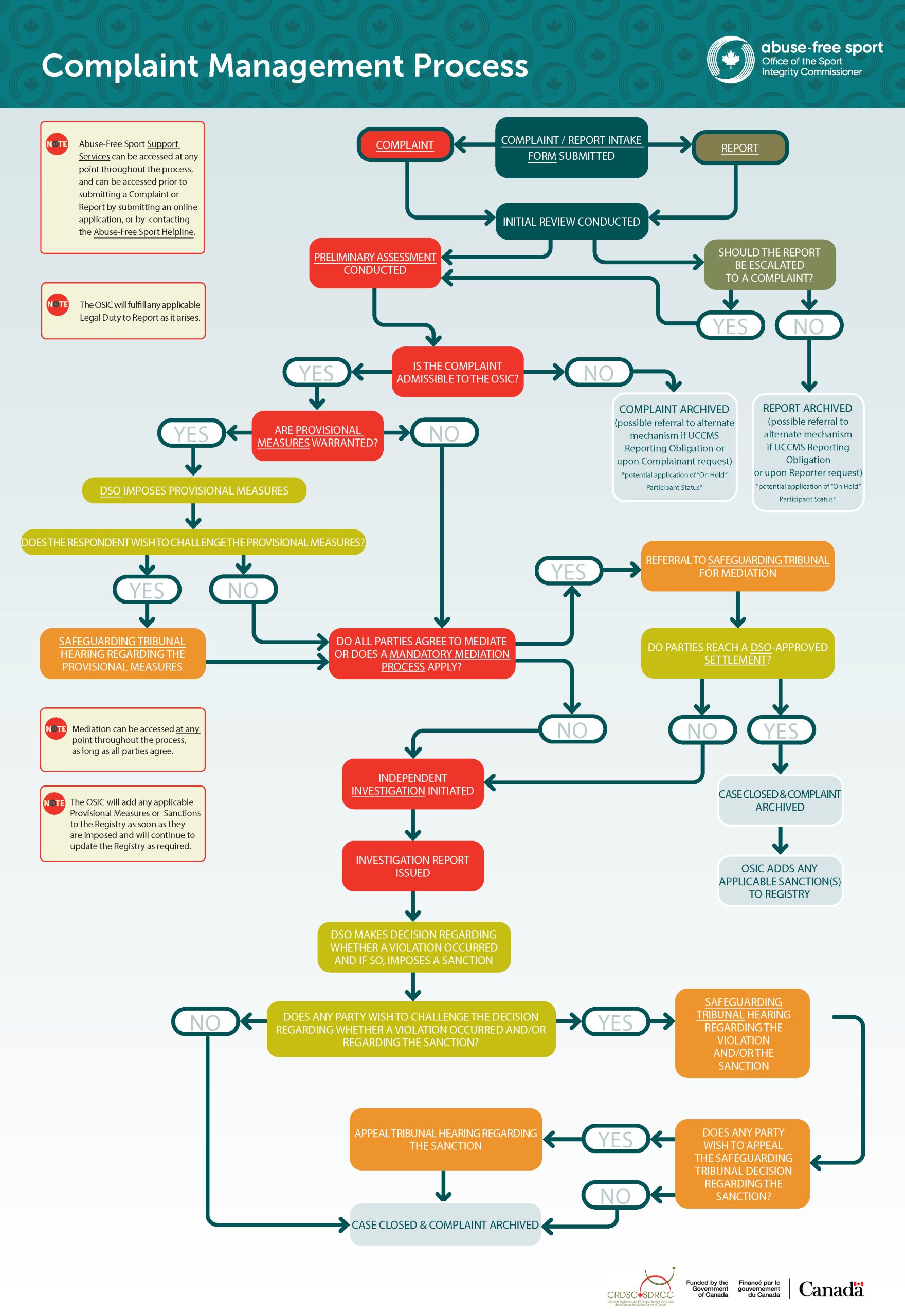

The inconsistency of reporting systems across different types of sports generates a sense of confusion among stakeholders. For example, the complaint management process previously developed by OSIC (see Figure 23.1) coveys a complex flowchart involving steps such as complaint, review, measure, tribunal, mediation, investigation and settlement.

Figure 23.1 OSIC’s Complaint Management System (previous model before CCES and CSSP)

Source: Abuse-free Sport.[5] [image description]

Reporting Based on Fear

In our current environment of safe sport implementation, fear impacts both youth athletes and coaches. The most vulnerable link in the system, the athlete, is relied on to make a report.[6] Solstad highlights the four fears athletes have of reporting as follows:[7]

Therefore, even when an athlete has identified and is experiencing maltreatment, there is not always a report made, regardless of the party the athlete is reporting to, allowing maltreatment behaviours to persist.

In reaction to the reporting systems, coaches are doing what they can to avoid being reported. There is a fear of false accusations (while rare, the belief persists), a fear of touching athletes even when needed for safety, and the fear of engaging in effective relations with athletes to fulfill their role as a coach.[8] With athletes and coaches each feeling a level of fear toward safe sport systems, there needs to be a better way to improve the safety of sport in a way that empowers athletes to be successful and encourages coaches—who are often volunteers—to continue their practice effectively.

Moving toward Safeguarding

Safe Sport tells coaches who they should not be (ie. someone who does maltreatment). But who are they supposed to be?

Moving forward, there needs to be a greater focus on Safeguarding to empower sport leaders towards action rather than reaction.

Safeguarding is a prevention-based model, rooted in human-rights principles, with the athlete’s needs at the forefront of management, and the benefits of sport applying to all participants.[9] As a prevention-based model, safeguarding does not rely on the occurrence of reported maltreatment to fix the issue. Safeguarding challenges our sport system by questioning how their structures may contribute to cases of maltreatment in the first place.

Guided through human rights, safeguarding aligns with international expectations for youth development. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) guarantees youth the highest standards of health, have the right to rest and leisure, and are protected through all measures to remove all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect, maltreatment or exploitation, while in the care of adults. Next, when athlete needs are at the centre of decision-making, winning at all costs mentalities dissipate, transforming sport programs.[10] Lastly, the benefits should apply to all participants—from youth athletes trying to find their footing in community sport to the elite athletes representing our country at international competitions.

What does Safeguarding look like?

Safeguarding begins with communicating and measuring the expectations of a sport organization. Komaki and Tuakli-Wosornu suggest that sport organizations use ‘carrots’ instead of ‘sticks’ to reinforce positive behaviours amongst coaches and other members.[11] For example, athletes would answer questions to an anonymous survey, reporting on the positive behaviours that their coach and organization exhibit. Using such information, a sport organization can coordinate plans for improvement.

Safeguarding methods like the example above could reduce the possibility for maltreatment to occur rather than weeding out maltreatment after it has happened. Survey communication could give coaches confidence that their teaching is meeting athlete needs, and the club greater confidence in their volunteer base’s alignment with safe values. Each part of the system would work together to make sport safe rather than relying heavily on athlete disclosures of maltreatment in safe sport. Any organization can apply safeguarding methods to improve its safety measures—a stark change from reacting to a case and relying on authorities beyond the organization to get involved in an investigation. Watch Video 23.1 shown below, to learn more about safeguarding from the perspectives of different stakeholders such as athletes, coaches, parents, health professionals, and researchers.

Video 23.1 Safe Sport to Safeguarding: 2025 Panel, Isaiah Clelland, Dr. Julie Stevens, Dr. Taylor McKee, Stevey Hildebrand, Jenna Cernjul, Zach Heipel, Aabroo Kaur, and Coach Tony

Video provided by Isaiah Clelland, Panel Host and Moderator, Centre for Sport Capacity, Brock University. Used with permission. [Transcript]

A Call to Action

Safe sport and safeguarding will continue to be vital functions of a safe sport system. While developing better reporting systems, I encourage sport leaders to continue finding ways to change the culture of sport toward safeguarding as the primary method of defence. Question the overall purpose of sport participation and whether our sport organizations meet those needs. Question the unnecessary power dynamics between administrators, coaches, parents, and athletes. Youth have a right to leisure free from maltreatment, therefore, it is our responsibility to construct an environment that promotes safety.

Future Research

Future editions of this volume would benefit from the inclusion of additional perspectives about safe sport, which are listed below. How can you contribute to research that would help to highlight these perspectives about safe sport?

- Indigenous perspectives;

- Perspectives of equity-deserving groups;

- Human, child and athlete rights;

- Legal and restorative justice approaches;

- Youth perspectives; and

- The perspectives of parents and guardians.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 23.1 This figure demonstrates the convoluted system of Office of the Sport Integrity Commissioner (OSIC) complaint management process. The flow chart details the process for handling complaints systematically, moving from an initial complain to review, provisional measures, investigation, decision, possible appeal and complaint closure. Overall, the image outlines the multiple steps from receipt of a complaint to final resolution. [return to text]

Sources

Baker, P. (2025, April 23). Fun Maps: Rethinking the Joy of Sport. The Sport Information Resource Centre. https://sirc.ca/articles/fun-maps-rethinking-the-joy-of-sport/.

Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport. (2025). Canadian Safe Sport Program. Retrieved May 7, 2025, from https://cces.ca/canadian-safe-sport-program.

Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute. (2022). Sport Participation Among Children and Youth. https://cflri.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CFLRI-Summary-1.-Sport-participation-of-children-and-youth.pdf.

Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariate. (n.d.). Red Deer Declaration – For the Prevention of Harassment, Abuse and Discrimination in Sport. Retrieved May 7, 2025, from https://scics.ca/en/product-produit/red-deer-declaration-for-the-prevention-of-harassment-abuse-and-discrimination-in-sport/.

Gurgis, J. J., Kerr, G., & Darnell, S. (2022). “Safe Sport Is Not for Everyone”: Equity-Deserving Athletes’ Perspectives of, Experiences and Recommendations for Safe Sport. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 832560–832560. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.832560

Inside the Games. (2025, February 5). Bach wants safe sport access for children. https://www.insidethegames.biz/articles/1151685/bach-calls-for-safe-sport-access-for-all.

Kerr, G. A., & Stirling, A. E. (2008). Child Protection in Sport: Implications of an athlete-centered philosophy. Quest (National Association for Kinesiology in Higher Education), 60(2), 307–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2008.10483583

Kerr, G., & Stirling, A. (2019). Where is Safeguarding in Sport Psychology Research and Practice? Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(4), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1559255

Komaki, J. L., & Tuakli-Wosornu, Y. A. (2021). Using Carrots Not Sticks to Cultivate a Culture of Safeguarding in Sport. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 625410–625410. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.625410

Marsollier, E., & Hauw, D. (2022). Navigating in the Gray Area of Coach-Athlete Relationships in Sports: Toward an in-depth analysis of the dynamics of athlete maltreatment experiences. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 859372–859372. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.859372

Pankowiak, A., Woessner, M. N., Parent, S., Vertommen, T., Eime, R., Spaaij, R., Harvey, J., & Parker, A. G. (2023). Psychological, Physical, and Sexual Violence Against Children in Australian Community Sport: Frequency, perpetrator, and victim characteristics. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(3–4), 4338–4365. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221114155

Parent, S., & Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P. (2021). Magnitude and Risk Factors for Interpersonal Violence Experienced by Canadian Teenagers in the Sport Context. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 45(6), 528–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520973571

Solstad, G. M. (2019). Reporting Abuse in Sport: A question of power? European Journal for Sport and Society, 16(3), 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2019.1655851

Tam, A., Kerr, G., & Stirling, A. (2021). Influence of the #MeToo Movement on Coaches’ Practices and Relations With Athletes. International Sport Coaching Journal, 8(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2019-0081

United Nations. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text.

Willson, E., Kerr, G., Battaglia, A., & Stirling, A. (2022). Listening to Athletes’ Voices: National Team Athletes’ Perspectives on Advancing Safe Sport in Canada. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4, 840221–840221. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.840221

- Willson et al., 2022 ↵

- CFLRI, 2022 ↵

- Parent and Vaillancourt-Morel, 2021 ↵

- Pankowiak et al., 2023 ↵

- “Complaint Management Process”, Process Overview. Abuse-Free sport, Office of the Sport Integrity Commissioner. Retrieved April 15, 2025 from https://sportintegritycommissioner.ca/process/overview. ↵

- Komaki & Tuakli-Wosornu, 2021 ↵

- Solstad, 2019 ↵

- Tam et al., 2021 ↵

- Gurgis et al., 2022; Kerr & Stirling, 2019; Marsollier & Hauw, 2022; United Nations, 1989 ↵

- Kerr & Stirling, 2008 ↵

- Komaki and Tuakli-Wosornu, 2021 ↵