11 Enforcement of Sanctions

Hilary Findlay

Marcus Mazzucco

Themes

Sports arbitration

Privacy law in sport

Contractual obligations

Learning Objectives

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

L01 Describe when a sanction issued under a code of conduct is considered final and binding;

L02 Identify the different pathways to challenge an arbitration decision that affirms or imposes a sanction for a code of conduct violation;

L03 Identify the purposes of publishing sanctions for code of conduct violations;

L04 Describe the privacy law principles that could govern the publication of sanctions; and

L05 Describe the legal obligations that could exist to enforce sanctions in the sport system.

Overview

This chapter examines the enforcement of sanctions issued under the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS). Part one discusses how sanctions affirmed or imposed in an arbitration decision can be challenged, as any such challenge will prevent a sanction from being final, binding, and capable of enforcement. Part two discusses considerations for the effective enforcement of sanctions issued under the UCCMS, including the publication of sanctions and related privacy law considerations, and the obligations that can be placed on participants in the sport system to enforce sanctions.

Key Dates

The focus of this chapter is on the enforcement of sanctions issued under the UCCMS from two perspectives: (1) challenges to an arbitration decision that imposes a sanction or affirms a sanction in an original decision, and (2) the enforcement of a sanction that is final.

1. Challenges to an Arbitration Decision

As discussed in Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution-Institutional Issues) and Chapter 10 (Dispute Resolution: Procedural & Substantive Issues), after an investigation into an alleged violation of the UCCMS, a decision-maker (the National Independent Mechanism (NIM) or the relevant sport organization) may make a decision about whether a violation occurred and, if so, what the appropriate sanction is. This is known as the original decision. Several parties may request an arbitration hearing to challenge the original decision. At the national level, the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC) will provide the arbitration services (see Figure 9.2 in Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution: Institutional Issues) for more information about the SDRCC). It remains to be seen whether the SDRCC or another institution will provide arbitration services at the provincial, territorial, and local levels of sport, should the UCCMS be implemented at those levels (see Chapter 7 (Jurisdiction) for a discussion on jurisdiction ).

At the arbitration stage, an arbitrator may conduct a new hearing to consider whether a violation of the UCCMS occurred and, if so, an appropriate sanction (this is known as a de novo hearing). Alternatively, the arbitrator may have a narrower scope of review that involves assessing the original decision for certain errors, such as procedural unfairness, the misinterpretation or misapplication of the UCCMS, or a disproportionate sanction.

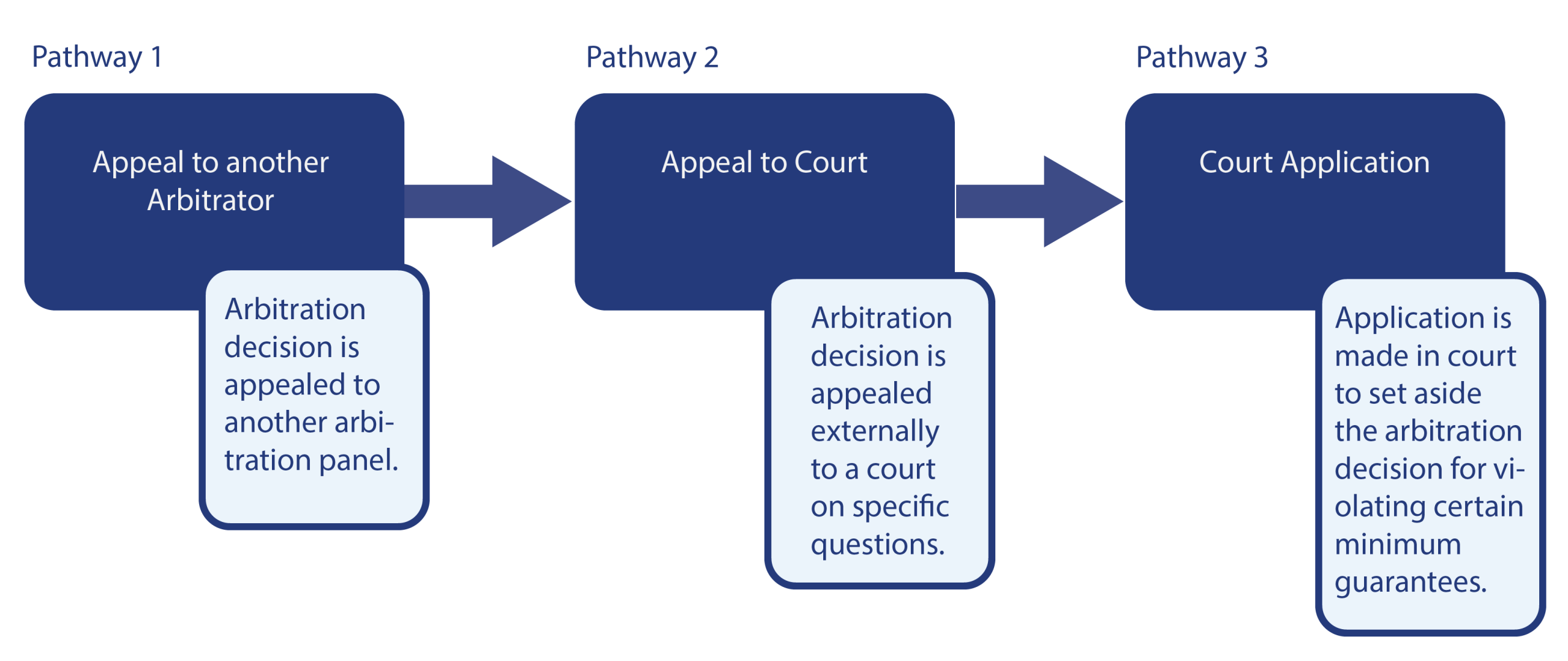

Once the arbitration decision is issued, the parties will need to decide whether they want to challenge the arbitration decision. There are three pathways for challenging an arbitration decision:

- An appeal to another arbitrator;

- An external appeal to a provincial or territorial superior court on specific questions; and/or

- An application to a provincial or territorial superior court to set aside the arbitration decision for violating certain minimum guarantees. Figure 11.1 below illustrates these different pathways.

As will be discussed later on in this section, the first two pathways (appeals to another arbitrator or court) may not be available in all cases; as a result, the pathways should not be considered sequential in nature. However, where the first two pathways are available, a party should move through the pathways sequentially, but only after considering the strength of their case to challenge the arbitration decision and whether it is worth spending the time and resources to bring the challenge.

Figure 11.1 Pathways for Challenging a Sport Maltreatment Arbitration Decision

Pathway 1: Appeals to Another Arbitrator

The availability of an appeal of an arbitration decision to another arbitration panel depends on the parties’ arbitration agreement (see Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution: Institutional Issues) for a discussion on arbitration agreements). In many cases, the arbitration agreement will specify that the arbitration proceeding will be conducted in accordance with the procedural rules of the arbitration institution (in Chapter 9 see “Example of an Arbitration Clause in a Sport Organization Policy or Contract”). For example, in the case of doping disputes, the SDRCC’s procedural rules specify that the arbitration decision of the SDRCC Doping Tribunal may be internally appealed to the SDRCC Appeal Tribunal.[1] The procedural rules also provide that decisions of the SDRCC Appeal Tribunal can be appealed by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) and the relevant international sport federation (IF) to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS), in accordance with the rules of the Canadian Anti-Doping Program (CADP). International-level athletes may also appeal decisions of the Doping Tribunal directly to CAS, in accordance with the CADP[2] (For more information about CAS, see in Chapter 9 “In Practice: Court of Arbitration for Sport)”.

In Canada, appeals of a sport arbitration decision to an external arbitration institution, such as CAS, are limited to doping cases. Some IFs may utilize a similar approach whereby the decision of an arbitration tribunal established by the IF is appealed externally to CAS, rather than internally within the IF’s arbitration tribunal. For example, decisions of the Dispute Resolution Chamber (an arbitration tribunal established by the Fédération Internationale de Football Association) can be appealed to CAS (see Figure 9.4 in Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution: Institutional Issues, for a visual representation).

In the sport maltreatment context, any rights to appeal an arbitration decision to another arbitration panel are limited to internal appeals within the arbitration institution. For example, in the United Kingdom (U.K.), arbitration decisions of the National Safeguarding Panel (NSP) can be internally appealed to an Appeal Tribunal within the NSP.[3] Similarly, in Canada, arbitration decisions of the SDRCC’s Safeguarding Tribunal can be internally appealed to the SDRCC’s Appeal Tribunal.[4] In contrast, in the United States (U.S.), arbitration decisions of the Judicial Arbitration Management Service (JAMS) cannot be appealed to another arbitration panel.[5]

In the context of the UCCMS, if there is a right to appeal an SDRCC arbitration decision, that appeal will very likely be to the Appeal Tribunal within SDRCC (an internal appeal), as opposed to an external appeal to CAS. The reason for this is that the UCCMS is a product of the Canadian sport system and disputes about it are best addressed through arbitration at the national level. In contrast, anti-doping rules are a product of the international sport system and although they apply at the national, provincial/territorial, and local levels of sport through national rules (i.e. the CADP), they retain a global element and explicitly provide appeal rights to international level organizations (e.g. WADA, IOC, IPC, IFs) that are best managed by an international arbitration institution (CAS).

How would an internal appeal of a SDRCC arbitration decision relating to the UCCMS work?

Some insight into this question can be obtained from the current procedural rules of the SDRCC, with the caveat that these rules may be revised as the SDRCC begins providing arbitration services as the NIM. Currently, a decision of the SDRCC Safeguarding Tribunal can be appealed to the SDRCC Appeal Tribunal, but only as the decision pertains to a sanction and only if the appeal is brought by a party that was before the Safeguarding Tribunal.[6] This means that a party who disagrees with the Safeguarding Tribunal’s finding on a violation of the UCCMS (i.e. that a violation occurred or did not occur) cannot bring an appeal to the Appeal Tribunal.

This narrow right of appeal to the SDRCC Appeal Tribunal may have implications for complainants. As was discussed in Section 1 of Chapter 10 (Dispute Resolution: Procedural & Substantive), under current SDRCC rules, only certain parties may request an arbitration hearing before the Safeguarding Tribunal. Complainants may request an arbitration hearing to challenge an original decision-maker’s finding about a code of conduct violation, but they cannot request an arbitration hearing to challenge a sanction imposed in an original decision.[7] As a result, if at the Safeguarding Tribunal, a complainant is successful in showing that a violation of the code of conduct occurred and that leads to the issuance of a sanction by the arbitrator, but that sanction does not satisfy the complainant, the complainant may not be able to appeal the arbitrator’s decision to the Appeal Tribunal, as the complainant did not have a right to challenge a sanction by arbitration in the first place. While this potential limitation on the appeal rights of a complainant may be consistent with the right of a complainant to request an arbitration hearing before the Safeguarding Tribunal, it raises the same questions about fairness and access to justice discussed in Section 1 “Rights to Request Arbitration” of Chapter 10 (Dispute Resolution: Procedural & Substantive).”

Other structural and procedural aspects of an appeal of a Safeguarding Tribunal decision to the Appeal Tribunal include the following:

- The Appeal Tribunal shall consist of a panel of three arbitrators, unless the parties agree to have a panel of one arbitrator;[8]

- No arbitrator on the panel of the Appeal Tribunal can have prior involvement in the case[9] to ensure their independence and impartiality for the reasons discussed in Section 1 of Chapter 10;

- The Appeal Tribunal’s scope of review shall take the form of judicial review, as opposed to a de novo hearing[10] (see Section 2 of Chapter 11 for more information about this scope of review);

- The Appeal Tribunal’s narrow scope of review means that it would not typically hear evidence from a minor or vulnerable person, but, if it did, then the flexible procedures used by the Safeguarding Tribunal would be available to the Appeal Tribunal[11] (see Tables 11.1 and 11.4 in Chapter 11 for more information about these procedures); and

- The publication of an Appeal Tribunal decision is governed by the same publication rules as decisions of the Safeguarding Tribunal[12] (see Section 4 of Chapter 11 for more information on this topic).

Pathway 2: Appeals to Court

The second pathway to challenge an arbitration decision involves an appeal to a provincial or territorial superior court (see Figure 9.3 in Chapter 9 (Dispute Resolution: Institutional Issues) for the organizational hierarchy of courts in Canada). Such appeals are governed by provincial/territorial arbitration legislation.

Arbitration decisions issued by the SDRCC are governed by Ontario law. As a result, any rights to appeal an SDRCC arbitration decision to the Ontario Superior Court of Justice are dealt with under Ontario’s Arbitration Act, 1991. The Arbitration Act, 1991 provides various appeal rights depending on whether the appeal involves a question of law, a question of fact or a question of mixed fact and law.

The “In Practice: Step into the Shoes of an Arbitrator” in Chapter 10 (Dispute Resolution: Procedural & Substantive Issues) provides an overview of what is considered a question of law, question of fact, and a question of mixed fact and law. As a refresher, a question of law is purely legal question, such as how a particular statute or regulation should be interpreted. In contrast, a question of fact is a question about whether a particular fact occurred. Finally, a question of mixed fact and law falls somewhere in the middle as it involves factual and legal elements. For example, assessing how a rule in a statute or regulation applies to a set of facts is a question of mixed fact and law. As another example, the interpretation of a contract is a question of mixed fact and law as it involves interpreting a legal document (a legal question) based on what the parties intended to agree upon (a factual question).[13]

As discussed in Chapter 8, the UCCMS will be implemented through contracts between sport organizations and participants. As a result, it is likely that a question about how to interpret the UCCMS will be considered a question of mixed fact and law, as opposed to a question of law. This is so, despite the fact that some scholars and arbitrators have described sport rules, such as codes of conduct, as quasi-legislative in nature (see Section 5 “Substantive Principles of Law for Interpreting the UCCMS” in Chapter 11). This distinction between a question of law and a question of mixed fact and law becomes important when we consider what appeal rights exist under Ontario’s Arbitration Act, 1991.

Section 45 of the Arbitration Act, 1991 provides the following rules for appeals of arbitration decisions:

- Questions of law can be appealed with permission of the court unless the arbitration agreement between the parties excludes such appeals;

- Questions of fact and questions of mixed fact and law can be appealed if the arbitration agreement between the parties includes such appeals.

With respect to appeals on questions of law, a court will only grant permission to hear the appeal if it is satisfied that the matters at stake in the arbitration are sufficiently important to the parties to justify an appeal and determining the question of law will significantly impact the rights of the parties (Arbitration Act, 1991). An example of a question of law that meets this threshold could involve an interpretation of a rule in a statute or regulation that will impact subsequent findings about whether an individual violated that rule and will be subject to a penalty.

The SDRCC’s procedural rules are inconsistent on the issue of appeal rights. The rules for the Ordinary Tribunal specify that its decisions are final and binding on the parties, and that there is no right of appeal on questions of law, questions of fact, or questions of mixed fact and law.[14] However, for decisions of the Safeguarding Tribunal that cannot be appealed to the SDRCC Appeal Tribunal and decisions of the Appeal Tribunal, the SDRCC rules state that the decisions are only final and binding on the parties. While this language means that there is no agreement to appeal an arbitration decision on a question of fact or a question of mixed fact and law, it does not explicitly exclude appeals on questions of law.

Courts have interpreted the phrase “final and binding” as not excluding rights of appeal on questions of law.[15] As a result, it is likely that a court would conclude that an arbitration agreement that incorporates SDRCC procedural rules does not exclude appeals of Safeguarding or Appeal Tribunal decisions on questions of law. However, it is unlikely that many sport arbitration decisions of the Safeguarding or Appeal Tribunal would be appealable on questions of law. As mentioned above, sport rules are considered contractual in nature, and the interpretation of those contracts involves a question of mixed fact and law, not a pure question of law. Accordingly, to the extent that a Safeguarding or Appeal Tribunal decision is limited to interpreting a sport rule and applying it to a set of facts, it does not raise a question of law that could be appealed under arbitration legislation. That said, there may be rare cases where a sport arbitrator does consider a pure question of law that would be appealable to a court under arbitration legislation, unless the arbitration agreement specifically excluded appeals on questions of law (see the Case Study below for one such example).

Case Study:

Case Study:

Adams v. Canada and the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (2011)

“Malicious Drugging and the Contaminated Catheter: Adams v Canadian Centre For Ethics in Sport” by Paul White, Sports Law eJournal, 2008.

Jeffrey Adams is a Canadian Paralympic athlete who competed at the international level in several wheelchair athletic events. As an international level athlete, Adams was subject to frequent doping control tests under the Canadian Anti-Doping Program (CADP). Adams was accused of an anti-doping rule violation and challenged the violation by arbitration at the SDRCC.

Adams alleged that the violation was due to a non-sterile catheter that he supplied for his doping control test, and that the CADP rules governing testing process were discriminatory against athletes with a disability as they did not require the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES) to supply athletes with a disability with a sterile catheter when providing a urine sample. Adams argued that this discrimination violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Charter), the Canadian Human Rights Act and Ontario’s Human Rights Code. The SDRCC Doping Tribunal found that neither the Charter nor the Canadian Human Rights Act applied to the CADP, and that the Ontario Human Rights Code, while applicable to the CADP, had not been violated. The Doping Tribunal also imposed a two-year ban for the doping violation.

Adams appealed the Doping Tribunal’s decision to CAS, in accordance with the CADP rules. CAS partially upheld Adams’ appeal by eliminating his period of ineligibility (as the violation was not due to his fault or negligence); however, CAS did not overturn the SDRCC Doping Tribunal’s findings regarding discrimination.

Subsequently, Adams attempted to bring an application for judicial review in an Ontario court to challenge the CAS decision. The Ontario court dismissed Adams’ application on the basis that arbitration decisions are not subject to judicial review and can only be challenged in accordance with the Arbitration Act, 1991. The court noted that appealing the CAS decision on a question of law under the Arbitration Act, 1991 was an option available to Adams. The question of law in this case involved the interpretation of the Charter and human rights legislation.

Pathway 3: Applications to Court

The final pathway to challenge an arbitration decision involves bringing a court application under provincial/territorial arbitration legislation to have a court set aside the decision for violating certain minimum standards set out in the legislation. The standards relate to the validity of the parties’ arbitration agreement and the fairness of the arbitration process. The rationale for this pathway is that parties cannot contract out of the court’s supervisory jurisdiction when they agree to resolve a dispute by arbitration. Courts have a responsibility to ensure that the arbitration process is fair and just for both parties.

In the case of SDRCC arbitration decisions, section 46 of the Ontario Arbitration Act, 1991 provides the Ontario Superior Court of Justice with the power to set aside an arbitration decision on several grounds. Table 12.1 below sets out these grounds and examples of when they might apply.

Table 11.1 Grounds for Setting Aside an Arbitration Decision

| Ground | Example |

|---|---|

| A party to arbitration agreement did not have legal capacity | A respondent did not have the mental capacity to enter into the arbitration agreement due to a cognitive disability. |

| The arbitration agreement is invalid | The arbitration agreement was signed by a party under duress, such as a threat of harm. |

| The arbitration decision deals with a dispute or covers a matter that is beyond the scope of the arbitration agreement | An arbitrator upholds a sanction against an athlete/respondent that involves a suspension from a team and selects another athlete to replace the respondent on the team. |

| The arbitration panel was improperly established | The arbitrator does not meet the qualifications set out in the arbitration agreement, such as a particular expertise or training in the subject-matter. |

| The subject-matter of the dispute is not capable of being subject to arbitration under Ontario law | Criminal matters, such as whether a respondent should be charged or convicted of a criminal offence. |

| Arbitration procedures did not comply with arbitration legislation | A procedurally unfair arbitration hearing where the arbitrator does not allow both parties to be heard. |

| Arbitrator committed fraud or was corrupt or there is a reasonable apprehension of bias | The arbitrator had a personal or financial relationship with one of the parties that resulted in the arbitrator treating one party more favourably than another or deciding the dispute in a pre-determined way to receive a benefit. |

| Arbitration award obtained by fraud | A party intentionally gives false evidence that shapes the outcome of the arbitration decision. |

2. Enforcement of Sanctions

Once a sanction is issued under the UCCMS and all attempts to challenge the sanction by arbitration or in court have been exhausted or waived, the final stage of the process is to enforce the sanction.

The effective enforcement of disciplinary sanctions is dependent on two factors:

(a) transparency or knowability of the sanction; and

(b) having obligations to enforce the sanction.

The final section of this chapter discusses both of these key issues.

Transparency of Sanctions

Objectives of Transparency

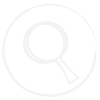

The transparency of a sanction serves several enforcement purposes.

First, knowledge of the sanction by someone other than the sanctioned individual may be necessary to implement aspects of the sanction. For example, if a coach is suspended from a national team, then the organizers of that team may need to take steps to remove the coach’s accreditations to take part in national team activities, such as training camps and international competitions.

Second, knowledge of a sanction is important to ensure that a system is in place to monitor and report on the sanctioned individual’s compliance with the sanction. A sanction that is not monitored for compliance is not effective and may undermine the purposes of the sanction.

Third, where a sanction is imposed due to concerns about an individual’s ability to participate in an activity without causing harm or increasing risk to other participants, then it is important for participants to be aware of the sanction to protect their interests.

Fourth, the knowability of a sanction advances the principles of denunciation and deterrence. Denunciation is a public disapproval of something or someone. While a code of conduct represents a public condemnation of certain behaviour, the public reporting of sanctions against an individual under that code of conduct further expresses a public disapproval of that behaviour and the particular individual’s actions. Deterrence is the act of discouraging undesired behaviour by instilling fear of punishment. The public reporting of a sanction acts as a deterrent for the general public as it serves as an example of the consequences that arise from certain behaviour. Figure 11.2 below illustrates how the above considerations apply in the sport maltreatment context.

Figure 11.2 Objectives of Publicly Reporting Sanctions in the Sport Maltreatment Context

The transparency of a sanction is closely related to the confidentiality of an arbitration process described in Section 6 of Chapter 11. However, as discussed in that section, publicizing or disclosing aspects of the arbitration process (such as an arbitration decision) involves a balancing of the purpose of the disclosure against the rights and interests of those impacted by the disclosure, such as the privacy interests of a respondent.

Based on the objectives set out in Figure 11.2 above, do you believe that sanctions issued under the UCCMS should be publicly disclosed? If yes, what level of information should be disclosed?

In the U.S., the Center for SafeSport has a centralized database that includes the following information about sanctions:

- The name of the respondent and their city and state of residence;

- The national sport organization affiliated with the respondent;

- A high-level description of the respondent’s misconduct (e.g. sexual misconduct);

- The sanctioned issued against the respondent (e.g. temporary suspension);

- Additional details relating to the sanction (e.g. no contact directive);

- The date of the sanction; and

- The adjudicator that imposed the sanction (e.g. Center for SafeSport).

The UCCMS describes a similar centralized database for reporting sanctions issued under the UCCMS. While the details of such a database are not yet known, the UCCMS specifies that the objective of the database is to track sanctions so that sport participants know who has breached the UCCMS and who is ineligible to participate in sport.

The Legality of Transparent Sanctions

The disclosure of identifying information about respondents who are sanctioned under the UCCMS raises an important legal consideration – namely, are there any privacy laws that restrict the public disclosure of identifying information about respondents sanctioned under the UCCMS and, if not, should there be?

In the case of the U.S. SafeSport model, this question is addressed by specific legislative authority for the centralized database. Section 220541(a)(1)(G) of chapter 36 of the United States Code authorizes the Center to “publish and maintain a publicly accessible internet website that contains a comprehensive list of adults who are barred by the Center.”

In Canada, there is no specific legislative authority for a database of individuals sanctioned under the UCCMS for the reasons discussed in Chapter 8 regarding Canada’s federal structure and the division of powers amongst federal, provincial, and territorial governments to enact laws. However, there also appears to be no legislative barrier to creating such a database at this time. Canadian privacy laws are comprised of various federal and provincial/territorial statutes. For example, Ontario has a Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) that governs the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by the government and hospitals (known as “institutions”), as well as an individual’s right to access records held by these institutions. Ontario also has a Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004 (PHIPA) that regulates the collection, use, and disclosure of personal health information by health care providers, medical officers of health, and the Ontario Ministry of Health. Neither of these statutes would regulate the publication of UCCMS sanctions by the NIM, as the NIM is not an institution within the meaning of FIPPA and would not be disclosing personal health information.

At the federal level, there are two privacy law statutes – the Privacy Act and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). The Privacy Act regulates the federal government’s handing of personal information and is not applicable to the NIM/SDRCC as the SDRCC is not part of the federal government as noted in Table 10.1 in Chapter 10.

PIPEDA applies to the personal information that a federally regulated organization collects, uses, or discloses about its employees (or an applicant seeking employment with the organization). A federally regulated organization includes airports, banks, inter-provincial or international transportation companies, telecommunications companies, as well as a work, undertaking or business outside the exclusive legislative authority of the legislatures of the provinces.[16] The SDRCC is considered a federally regulated organization as it is created under federal legislation (the Physical Activity and Sport Act) and its mission to provide a national alternative dispute resolution service for sport disputes is outside the legislative authority of provinces. However, the SDRCC/NIM’s publication of sanctions under the UCCMS would not involve the personal information of employees of the SDRCC; it would involve the personal information of respondents. As a result, the publication would not be regulated under this aspect of PIPEDA.

PIPEDA also applies to any private organization that collects, uses, or discloses personal information in connection with a commercial activity. “Commercial activity” means an act that is of a commercial character.[17] It seems unlikely that the NIM/SDRCC’s disclosure of information about sanctions issued under the UCCMS would be considered “in connection with a commercial activity”. The purpose of the disclosure is to address and prevent maltreatment in sport and does not have a commercial character.

A similar interpretation of PIPEDA was taken in relation to the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information by WADA for its interprovincial and international anti-doping activities. WADA’s headquarters are in Montreal, Quebec, and its handling of personal information within the province is subject to Quebec’s private sector privacy legislation. However, WADA’s use of personal information for interprovincial and international anti-doping activities is not regulated under the Quebec legislation, and, up until 2015, was not regulated under PIPEDA. PIPEDA did not apply to WADA as it is not a federally regulated organization and is not engaged in commercial activities.

This gap in the application of Canadian privacy laws concerned some European Union countries as sensitive personal information about their athletes was being collected, used, and disclosed by WADA’s headquarters in Montreal. To address these concerns, the federal government amended PIPEDA in 2015 to extend its application to the personal information collected, used, and disclosed by WADA’s headquarters for interprovincial and international anti-doping activities.[18] The amendment to PIPEDA was significant as it set a precedent to broaden the application of the legislation to include an organization that is not a federally regulated organization or otherwise engaged in commercial activities.[19]

The timing of the amendments to PIPEDA to include WADA in 2015 was auspicious as a year later, WADA was the victim of a significant privacy breach by the hackers known as “Fancy Bear” who accessed the personal information of thousands of athletes and posted the information on its website. The personal information included confidential and sensitive medical information about athletes who had therapeutic exemptions to use prohibited substances under anti-doping rules. Because WADA was subject to PIPEDA at the time of the privacy breach, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada had jurisdiction to investigate the breach and enter into a compliance agreement with WADA to implement certain remedial measures identified during the investigation.

The lesson from WADA’s privacy breach is it is important from an accountability perspective to have laws that protect the personal information collected, used, and disclosed by organizations. While an organization that is not subject to privacy legislation can have robust internal policies and controls to safeguard personal information from improper use and access, the reality is that privacy breaches can happen and, if they do, it is preferable to have a legislative framework in place to ensure accountability for the breach and the remedial steps required to contain the breach and prevent similar breaches in the future.

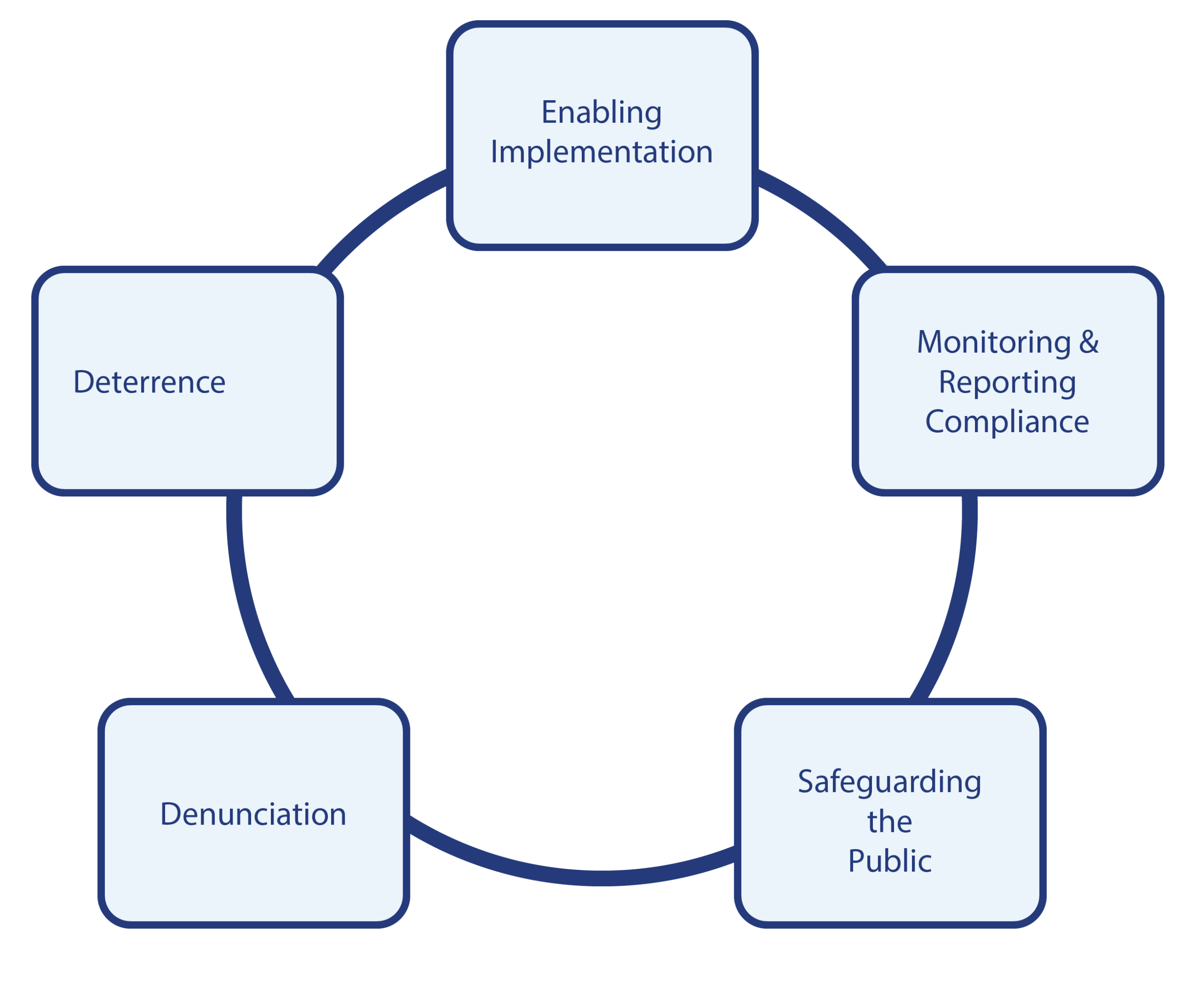

PIPEDA imposes the following ten fair information principles for organizations subject to the legislation as outlined in Figure 11.3.

Figure 11.3 PIPEDA Information Principles

Should the NIM’s collection, use and disclosure of personal information in relation to administering the UCCMS be subject to the requirements of PIPEDA? The publication of sanctions imposed under the UCCMS is only one component of the NIM’s responsibilities. In overseeing the implementation of the UCCMS in Canada, the NIM will collect, use, and disclose significant amounts of sensitive personal information about complainants, witnesses, and respondents due to NIM’s multiple roles as an overseer, investigator, and adjudicator. The above analysis about the application of PIPEDA to the NIM only relates to the publication of sanctions.

Consideration should be given as to whether NIM is subject to PIPEDA in respect of its collection, use, and disclosure of personal information for activities other than the publication of sanctions. If it is not, then it is recommended that PIPEDA be amended to capture all of the NIM’s activities involving the handling of personal information. If PIPEDA’s requirements and principles apply to the NIM, then the NIM will need to ensure that it has a respondent’s consent before publicly disclosing information about their UCCMS sanction. This consent should be obtained prior to any investigation or arbitration hearing regarding a violation of the UCCMS to avoid a scenario where a respondent declines to grant consent at a time when they are at risk to receive a sanction. Ideally, the contractual process used to make the respondent subject to the UCCMS as a condition of participating in a sport should be leveraged to include a consent to any future publication of a sanction issued under the UCCMS.

Obligations to Enforce Sanctions

The second key aspect of the effective enforcement of sanctions is ensuring that they are respected by the respondent, sport organizations and participants in the sport system. As McLaren Global Sport Solutions (2020) noted in its study of independent approaches to administer the UCCMS, “the enforcement of issued sanctions will be, for all intents and purposes, a team effort for it to be effective across the sport sector”.[20] This principle may seem simplistic, but from a legal perspective it requires a consideration of who should have an obligation to respect the sanction and where that obligation comes from. The UCCMS sets out rules for the imposition of sanctions against a respondent who has engaged in maltreatment. However, the rules do not describe how the sanction would be enforced from the perspective of the respondent or sport organizations.

Obligations on Respondents

With respect to the respondent’s legal obligation to comply with the sanction, this obligation may arise from two sources. First, if the respondent is a party to a contact with a sport organization, then that contract may include a provision that requires compliance with the UCCMS, including any sanction issued under the UCCMS. If the respondent fails to comply with the sanction in accordance with the contract, then they could be sued for breach of contract. However, in the case of a temporary suspension or permanent eligibility, these sanctions may result in the termination of the respondent’s contract with the sport organization. Once the contract is terminated, any obligation to comply with the UCCMS ends, unless the parties agreed that the obligation survives the termination of the contract.

A second potential source of a respondent’s obligation to comply with a sanction is a court order. If the sanction is imposed on the respondent following an arbitration hearing, then a provincial or territorial superior court can issue an order enforcing the arbitration decision. For example, section 50 of Ontario’s Arbitration Act, 1991 provides that a person who is entitled to enforcement of an award made in Ontario or elsewhere in Canada may make an application to the court for an order to that effect. If such a court order is issued, and a respondent refuses to comply, then they can be held in contempt of court and charged with a criminal offence under section 127 of the Criminal Code.

Obligations on Sport Sector

While the above obligations that can be imposed on a respondent are helpful, they are unlikely to be the primary tool used to ensure compliance with a sanction. The true effectiveness of a sanction is dependent on the ability of others in the sport system to respect it. For example, if a respondent is suspended from participating in all coaching activities in a particular sport, then all organizations and participants within that sport have a moral responsibility to implement the sanction by refusing to engage with the respondent in a coaching capacity during the length of the suspension. Depending on the organization or participant, fulfilling this responsibility may involve terminating an employment, service, or lease agreement with the respondent, or ending a coaching relationship with the respondent.

Ideally, organizations and participants will carry out this responsibility to follow sanctions through their shared commitment to prevent and address maltreatment in sport. However, for some, the desire to succeed in sport may trump this responsibility and lead to instances where an organization or participant wants to continue having a business or professional relationship with a respondent, even though such a relationship will result in the respondent violating a sanction imposed under the UCCMS (see the Case Study below). As a result, it becomes necessary to consider how a moral responsibility to uphold UCCMS sanctions can be supplemented by legal obligations.

The anti-doping movement is a helpful comparator when considering the responsibilities of levels of the sport sector. Article 10.14.1 of the World Anti-Doping Code (2021a) provides that, when an athlete or other person is subject to a period of ineligibility, they cannot participate in any capacity in a competition or activity (other than anti-doping education or rehabilitation programs) authorized or organized by any signatory of the World Anti-Doping Code, any member of a signatory, or any club or other member organization of a signatory’s member organization, or in competitions authorized by any professional league or any international- or national-level event organization or any elite or national-level sporting activity funded by a governmental agency. This rule captures virtually every aspect of the sport system. Compliance with sanctions by the sport sector is also achieved through article 15 of the World Anti-Doping Code and the International Standard for Code Compliance by Signatories, which require signatories to enforce anti-doping sanctions and report on this enforcement, along with other compliance requirements.[21] Once the obligation to enforce the sanction is imposed on the signatory of the World Anti-Doping Code (e.g. CCES, Canadian Olympic Committee, Canadian Paralympic Committee), it becomes the signatory’s responsibility to ensure that this obligation is also met by any organizations that are members of or affiliated with the signatory. This trickle-down effect allows for anti-doping sanctions to be enforced at almost all levels of the sport system. However, as seen in the Case Study here, enforcement of a sanction can still be difficult and requires the collective action of all participants.

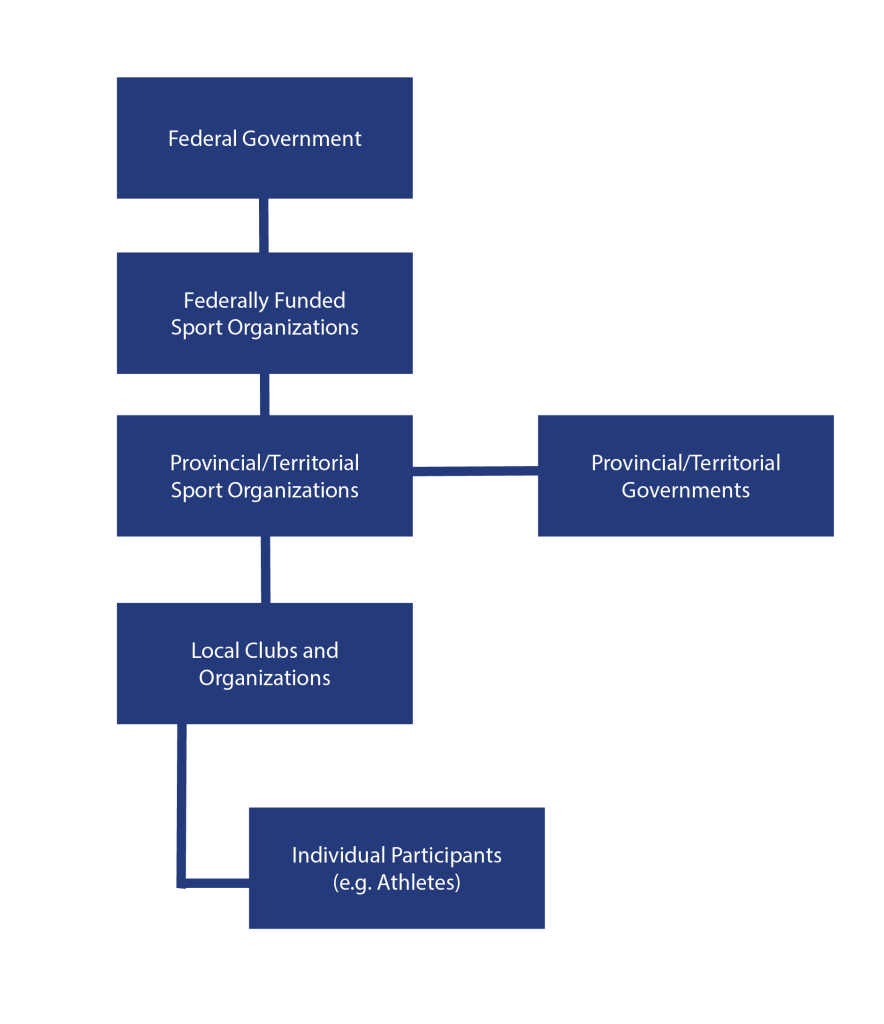

Returning to the sport maltreatment context, in the U.S., the requirement for sport organizations to comply with sanctions issued by the U.S. Center for SafeSport arises from legislation. In accordance with section 220505(d)(1)(C) of Chapter 36 of the United States Code (2021), the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee, national sport governing bodies and local affiliated organizations are responsible for enforcing eligibility determinations and sanctions imposed by the Center for SafeSport. Such legislation does not exist in Canada. However, the obligation to comply with UCCMS sanctions could be imposed on organizations and participants using the contractual framework discussed in Chapter 7 (Jurisdiction). This contractual framework (see Figure 11.4) could be similar to that used in the anti-doping movement and can be described using a top-down approach, as follows:

- Sport organizations that are funded by the federal government have an obligation to implement the UCCMS within their organization as a condition of their funding agreement with the federal government. This obligation could include ensuring that all organizational members of the federally funded organization also comply with the UCCMS. For example, in the case of a national sport organization (NSO), the NSO could have a duty to ensure that all provincial and territorial organization members (PTSOs) of the NSO also implement the UCCMS within their own organizations. In addition, if the NSO has any contractual relationships with individual participants (e.g. athletes or coaches), such as national team agreements or entry rules for competitions hosted by the NSO, then those agreements/rules could include a requirement to comply with the UCCMS.

- PTSOs that are members of NSOs could have an obligation to implement the UCCMS within their organization as a condition of being a member of the NSO. This obligation could be supplemented by provincial and territorial governments that provide funding, directly or indirectly, to PTSOs, through conditions in funding agreements. The obligations of a PTSO could include ensuring that all organizational members of the PTSO also comply with the UCCMS, such as local clubs and organizations. In addition, if the PTSO has any contractual relationships with individual participants (e.g. athletes or coaches), such as provincial/territorial team agreements or entry rules for competitions hosted by the PTSO, then those agreements/rules could include a requirement to comply with the UCCMS.

- Local clubs and organizations that are members of a PTSO could have an obligation to implement the UCCMS within their organization as a condition of being a member of the PTSO. The obligation could include ensuring that all employees and members of the organization, such as athletes, parents, and coaches agree to comply with the UCCMS through employment contracts and member agreements, as applicable.

Figure 11.4 Contractual Relationships in Sport to Enforce Sanctions

Obligations on Government Funders of Sport

A final consideration is what obligations can be imposed on governments that publicly fund sport organizations to ensure the enforcement of sanctions imposed under the UCCMS. For many years, federally funded sport organization have been required to have policies to deal with incidents of harassment and abuse, to have arm’s length trained harassment officers, and to report to Sport Canada annually on their compliance with these requirements.[22] However, as discovered in a 2016 study, many sport organizations have encountered difficulties in implementing these requirements and the requirements are not being enforced by the federal government under funding agreements[23] (challenges such as these were further addressed in Chapter 6). As the implementation of the UCCMS is now a requirement for federally funded sport organizations under funding agreements with Sport Canada, there is a fresh opportunity for Sport Canada to ensure that sport organizations comply with this requirement to implement the UCCMS, which includes the enforcement of sanctions issued under the UCCMS.

However, based on the federal government’s history in enforcing funding requirements, there is reason to be skeptical of their ability or willingness to enforce. As a result, it is necessary to consider what mechanisms exist to improve the federal government’s accountability to enforce the funding conditions.

Alternate options to enforce sanctions imposed under the UCCMS through publicly funded sport organizations include:

- Members of the sport community advocating for change by contacting their Members of Parliament;

- Continuing to conduct scholarly research on sport organizations’ compliance with implementing safe sport funding policies and to publish those findings to bring continued awareness to the issue; and

- Members of the sport community requesting that government oversight bodies, such as the Auditor General of Canada and the Taxpayers’ Ombudsman, make inquiries into the federal government’s management and enforcement of agreements with federally funded sport organizations. As these agreements involve the expenditure of taxpayer funds, members of the sport community have a clear interest in ensuring that those funds are spent appropriately.

These options would also be available a the provincial, territorial, and local levels of sport, should the UCCMS be implemented at these levels.

Further Research

The final part of this chapter examined how legal obligations to enforce sanctions can be imposed primarily within the sport system through a web of contracts between organizations and participants. What mechanisms external to the sport system could be used to ensure the enforcement of sanctions under the UCCMS? For example, could insurance providers make it a best practice for sport organizations to comply with the UCCMS through their insurance contracts?

Key Terms

Suggested Assignments

- Compare and Contrast with the Anti-Doping Rules: Anti-doping rules are imposed on sport participants based on a web of contracts similar to that described and depicted at the end of this chapter (see Figure 11.4). Can you identify any differences between these two contractual frameworks?

Figure Descriptions

Figure 11.1 This figure demonstrates the pathways for challenging a sport maltreatment arbitration decision. First is the appeal to another arbitrator, where the arbitration decision is appealed to another arbitration panel. Next comes the appeal to court, where the arbitration decision is appealed externally to a court on specific questions. Lastly is the court application, where the application is made in court to set aside the arbitration decision for violating certain minimum guarantees. [return to text]

Figure 11.2 This figure demonstrates the objectives of publicly reporting sanctions in the sport maltreatment context. There are five elements in this continuous circle including enabling implementation, monitoring & reporting compliance, safeguarding the public, denunciation, and deterrence. [return to text]

Figure 11.3 This figure demonstrates the ten Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) principles. Accountability – An organization is responsible for personal information in its possession or control and must assign someone to be responsible for ensuring compliance with PIPEDA and its principles. Identifying purposes – An organization must identify the purpose for any collection, use, or disclosure of personal information it carries out. Consent – An organization must obtain the informed consent of an individual in order to collect, use, or disclose their personal information, unless an exception applies. Limiting collection – An organization cannot collect more personal information than is necessary to meet the purpose of the collection. Limiting use, disclosure and retention – An organization can only use and disclose personal information for the purpose for which it was collected, unless the individual consents to the use or disclosure for a different purpose. An organization must also only retain personal information for as long as required to meet the purpose of a collection, use or disclosure. Accuracy – An organization must ensure that the personal information in its possession or control is accurate, complete, and up-to-date. Safeguards – An organization must secure personal information using measures that are proportional to the sensitivity of the information. Openness – An organization must be transparent about its policies and practices for handling personal information. Individual access – An organization must respect an individual’s right to be informed about the existence, use and disclosure of their personal information, their right to access their personal information, and their right to correct errors in their personal information. Challenging compliance – An organization can be the subject of an individual’s complaint about non-compliance with PIPEDA. [return to text]

Figure 11.4. This diagram demonstrates contractual relationships in sport to enforce sanctions. At the top of the branching scenario is the federal government, beneath that are federally funded sport organizations, and beneath that are provincial/territorial sport organizations (PTSOs), of which provincial/ territorial governments are a branch. Local clubs and organizations are one level below PTSOs, and individual participants (e.g. Athletes) are listed as the very last branch. [return to text]

Sources

Adams v. Canada and Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (2011), 2011 ONSC 325

Arbitration Act, 1991, Ontario, Canada.

Canadian Anti-Doping Program (CADP). (2021). Canadian anti-doping program: Part C – Canadian anti-doping program rules. https://cces.ca/sites/default/files/content/docs/pdf/2021-cces-policy-cadp-2021-final-draft-e.pdf

Canadian Safe Sport Program. (2020). Sport Information Resource Centre: Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS), (5)1, 1-16. https://sirc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/UCCMS-v5.1-FINAL-Eng.pdf

Criminal Code, C, s 127.

Designation of United States Center for SafeSport, 36 USC 220541 (2021).

Donnelly, P., & Kerr, G. (2018). Revising Canada’s policies on harassment and abuse in sport: A position paper and recommendations. Centre for Sport Policy Studies Positions Paper. https://kpe.utoronto.ca/sites/default/files/harassment_and_abuse_in_sport_csps_position_paper_3.pdf

Donnelly, P., Kerr, G., Heron, A., & DiCarlo, D. (2016). Protecting youth in sport: An examination of harassment policies. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 8(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2014.958180

Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. F.31. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90f31

Government of Canada. (2021, November 15). Office of the taxpayers’ Ombudsperson. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://www.canada.ca/en/taxpayers-ombudsperson.html

McLaren Global Sports Solutions. (2020). Aim High: Independent approaches to administer the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport in Canada, final report. https://sirc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/MGSS-Report-on-Independent-Approaches-December-2020.pdf.

Office of the Auditor General of Canada. (n.d.). Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/english/admin_e_41.html

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada. (2015, June 1). Submission to the standing senate committee on national finance. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/opc-actions-and-decisions/advice-to-parliament/2015/parl_sub_150601/

Personal Health Information Protection Act, S.O. 2004. c. 3. Retrieved December 9, 2021, from https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/04p03

Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, S.C. 2000. c. 5. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/P-8.6.pdf

Piazza Family Trust v. Veillette (2011), ONSC, [2011] O.J. No. 2094

Privacy Act, R.S.C. 1985. c. P-21. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/P-21.pdf

Sattva Capital Corp. v. Creston Moly Corp. (2014), SCC, [2014] S.C.J. No. 53

Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC). (2021). Canadian sport dispute resolution code. http://www.crdsc-sdrcc.ca/eng/documents/Code_SDRCC_2021_-_Final_EN.pdf

Sport Resolutions. (2021). 2021 procedural rules of the national safeguarding panel. https://www.sportresolutions.com/images/uploads/files/2021_NSP_Procedural_Rules_-_23.07.2021.pdf

Starkman, R. (2007, June 22). Lifetime swim ban sinks like a rock. Toronto Star. Retrieved December 8, 2021, from https://www.thestar.com/sports/olympics/2007/06/22/lifetime_swim_ban_sinks_like_a_rock.html?rf

U. S. Center for SafeSport. (n.d.). SafeSport code. Retrieved December 5, 2021, from https://uscenterforsafesport.org/response-and-resolution/safesport-code/

World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). (2021a). World anti-doping code 2021. https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/2021_wada_code.pdf

WADA. (2021b). International standard for code compliance by signatories 2021. https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/international_standard_isccs_2021.pdf

- SDRCC, 2021 ↵

- SDRCC, 2021 ↵

- Sport Resolutions, 2021 ↵

- SDRCC, 2021 ↵

- U.S Center for SafeSport, 2021 ↵

- SDRCC, 2021 ↵

- SDRCC, 2021 ↵

- SDRCC, 2021 ↵

- SDRCC, 2021 ↵

- SDRCC, 2021 ↵

- SDRCC, 2021 ↵

- SDRCC, 2021 ↵

- Sattva Capital Corp. v. Creston Molly Corp., 2014 ↵

- SDRCC, 2021 ↵

- Piazza Family Trust v. Veillette, 2011 ↵

- PIPEDA, 2000 ↵

- PIPEDA, 2000 ↵

- WADA’s use of personal information for anti-doping activities in Quebec remains subject to Quebec’s private sector privacy legislation. ↵

- Privacy Commissioner of Canada, 2015 ↵

- McLaren Global Sport Solutions, 2020, p. 53 ↵

- WADA, 2021a; WADA, 2021b ↵

- Donnelly & Kerr, 2018 ↵

- Donnelly et al., 2016 ↵

Universal Code of Conduct to Address Maltreatment in Sport, promulgated in 2020.

Independent body charged with overseeing operational aspects of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS). In Canada, the SDRCC has been named as the NIM to oversee the UCCMS. A regulatory body with the authority to implement safe sport policies.

A decision made by a decision-maker (the National Independent Mechanism [NIM] or the relevant sport organization) about whether a violation occurred and, if so, what the appropriate sanction is.

Independent agency to provide athletes and other participants in the national sports system with an opportunity to have independent arbitrators consider their appeals against decisions they feel were unfair. Now charged with the responsibility to provide an independent mechanism to address maltreatment in Canadian sports.

A process whereby parties refer their dispute to a mutually acceptable, knowledgeable, independent person (an arbitrator) to determine a resolution.

An option for challenging an arbitration decision, if agreed to by the parties. It involves appealing an arbitration decision to a different arbitrator or arbitration panel within the same institution as the arbitrator who made the decision being challenged.

Provincial or territorial legislation that governs private arbitration proceedings, including challenges to arbitration decisions. The Ontario Arbitration Act, 1991 is an example.

Purely legal question, such as how a particular statute or regulation should be interpreted.

A question about whether a particular fact occurred.

Falls somewhere in the middle of a question of law and a question of fact as it involves factual and legal elements.

An option for challenging an arbitration decision, if permitted under arbitration legislation. It involves filing an application in court on the grounds that the arbitration process failed to meet certain minimum standards of fairness as set out in the arbitration legislation.

A public disapproval of misconduct or a person who has committed misconduct; can be a purpose of publicly disclosing sanctions for misconduct.

The act of discouraging misconduct by instilling fear of punishment; can be a purpose of publicly disclosing sanctions for misconduct.

Federal privacy legislation that regulates the handling of personal information by federally regulated organizations and private organizations in certain circumstances, including WADA. The legislation requires an organization to obtain a person’s consent before handing their personal information, as well as comply with other information practices.

A duty to do something that arises from a statute, contract, or other legal instrument that usually results in consequences if the duty is not carried out; can be differentiated from a moral duty.