19 Creating Safe, Equitable, Diverse and Inclusive Cultures for Sports Officials

Susan L. Forbes

Lori A. Livingston

Themes

Safe sport environment

Equity, diversity and inclusion

Institutionalized sport culture

Learning Objectives

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

LO1 Critically examine sociocultural factors that create a less than inclusive officiating environment;

L02 Identify key components of effective officiating education and training programs; and

L03 Identify the barriers to an inclusive sports environment.

Overview

Sport officials play a critical role in upholding both the spirit and the letter of the laws (or rules) to ensure that all competitors are given an opportunity to compete in a predictable and safe environment that is both fair and equitable. They are an essential part of the sport ecosystem, yet they have been historically marginalized and besmirched as sports’ “necessary villains.” This prevailing culture continues today with officials finding themselves challenged by angry athletes, coaches, and spectators, and with these situations often escalating into harmful verbal and physical confrontations. This chapter begins with a brief review of the factors which contribute to unsafe environments for officials, followed by the presentation of key concepts and strategies to counter this problem. Importantly, the creation of equitable, diverse, and inclusive sport environments is the key.

Key Dates

Organized sport necessitates the involvement of numerous categories of participants, including those who organize competitions, leagues, and clinics for others who wish to join in as athletes, coaches, other specialized roles (e.g., team managers, trainers, etc.), or simply as spectators. Arguably the least celebrated, or appreciated, yet the most essential category of sport participants are those who opt into roles as competition officials (e.g., umpires, referees, judges, scorers, and timers). This may seem like a rather bold statement, but it is valid for two reasons.

First, without rules and the officials who enforce them, sport by definition is merely reduced to play. [1] The second, and no less important to understand, is that officials are frequently criticized and demeaned for the role that they play.[2] Officials understand that criticism is part of the job,[3] yet the problem today is that all too frequently the verbal airing of a concern turns into a threat of violence which could jeopardize their physical and or psychological safety.[4]

For over a century, sport officials have been viewed in a negative light and belittled for the job that they perform. There is ample evidence of this in the sport history literature, [5] but these overt critiques have been exponentially amplified in recent years, thanks to a number of contributing factors including the evolution of technology. For example, real time video review of officiating decisions began in 1985 when the United States Football League first introduced the concept as part of its televised broadcasts.[6]

Officials’ split second decisions were now being explicitly questioned for the first time through retroactive review. But these have evolved from real time replays of relatively low resolution video images at that time to today’s high-resolution ultra-slow motion frame-by-frame replays which reveal the minutest of details.

Further, these reviews are also no longer restricted to the domain of televised sport. By using their cell phones, spectators at youth sporting events are able to capture high-definition video and camera images which are shared widely thanks to the increasing popularity of social media platforms. These tools are making it easier for critiques – warranted or unwarranted – to be aired with greater frequency than ever before. As a result, this criticism is becoming increasingly aggressive and intimidating, or harassing, and is often coupled with verbal taunts and threats of physical harm.

Data on the incidence of such events is rare, yet it is estimated that 15% of all youth sport competitions in the United States involve some sort of verbal or physical abuse directed at officials from coaches and parents.[8] All too often these overt taunts include sexist, racist, and or homophobic overtones,[9] which are deliberately meant to humiliate and demean. Sadly, a simple search of the World Wide Web using the terms “hockey or soccer referee” and “assault” yields hundreds of media reports of such incidents from around the globe. Concern over the increasing frequency and severity of these attacks is leading many U.S. states to enact legislation to address physical and verbal threats directed at sport officials,[10] but criminalizing these acute actions does not guarantee that officials will be safe.

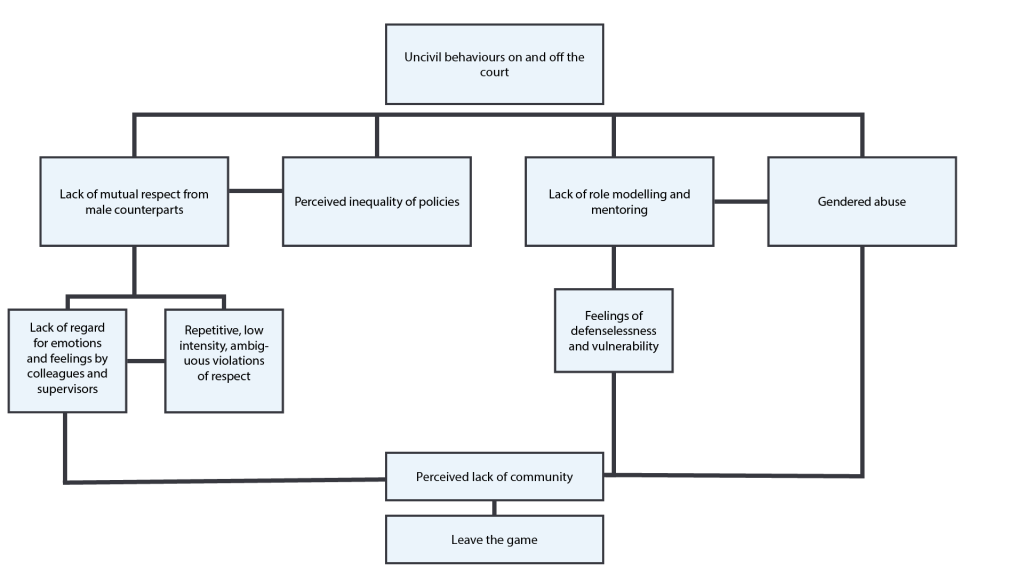

Acts of aggression may also be chronic or systemic in nature and emerge in more subtle or ambiguous forms such as microaggressions or periodic incidents of incivility.[11] The experiences of female basketball officials offer some clear illustrations of these types of phenomena. A qualitative study of former female basketball referees in different parts of the U.S. identified four themes that were related to and led to their decisions to leave. [12] In terms of the organizations to which they belonged, and in comparison to their male peers, there was a lack of mutual respect for their abilities, perceived inequities in the application of policies and processes, a lack of role modeling and mentoring, and gendered abuse. (See Figure 19.1 below.)

Claire Schaeperkoetter’s (2017) autoethnography of her experiences as a female official in the sport of men’s basketball sadly identifies many of the same issues. Her story paints a disturbing picture of the gendered perceptions and lack of respect afforded to her by players, coaches and fans and the challenges she faced as a result. Her story is also one of drop out from the officiating ranks as a result of heightened levels of stress, frustration, and emotion. More recently, a high-profile incident involving LeVar Ball, a controversial coach of a team playing in an event showcasing high school boys’ basketball talent, also more than amply illustrates the existence of sexism in sport.[13]

The harassment of sport officials has been described as a situation that is “out of control” and one that is leading many U.S. states to implement legislation in an effort to protect sport officials.[14] However, the imposition of punitive fines and measures alone will not be sufficient to deter or resolve the issues that exist today. The root of the problem begins within the institution of sport itself, and keeping sport safe for officials needs to begin with the identification of longstanding and well entrenched institutionalized inequities that have for too long served to marginalize and demean officials,[15] rather than seeing them as valuable assets within sport. To this end, here are five different strategies for sport organizations to consider in their efforts to create more supportive, positive, and safe environments for their officials.

In the News:

Referees and Mental Health

“Referees & abuse: ‘Massive rise in mental health support requests‘” by Ben Croucher, BBC Sport, November 14, 2020.

Following COVID-19 lockdowns in the United Kingdom, Ref Support UK saw a massive increase in football (soccer) officials seeking mental health support. In a new book, Referees, Match Officials & Abuse, 93.7% of match officials interviewed said they have experienced verbal abuse. Of the 2,056 referees in England surveyed, more than nine in ten said they had been verbally abused, with 59.7% experiencing some form of abuse every two games.

Do you think officials in some sports experience more abuse than officials in other sports? What data can you find on referee abuse in your sport?

Figure 19.1 Why Female Basketball Referees Leave the Game

Case Study:

Baseball Canada

Baseball Canada held a workshop entitled Gendering Realities: The Differing Experiences of Male vs. Female Sports Officials at their 2017 Fall Convention. Using data drawn from a national study, this workshop explored the gendered challenges in sports officiating as well as dealing with sexual violence, and how sports administrations could develop more inclusive officiating environments.

Key Concepts and Strategies

The sociocultural environments found in sport are complex and the product of current and historical initiatives and issues including participation policies, evolving legislation, longstanding public beliefs, and culturally driven social constraints.[16] These environments vary considerably from sport to sport and significantly influence the participant experience. For officials, there is one consistent and constant feature of their environment that has persisted over time; that is, the presence of constant critique.

To be realistic, it is more than likely that criticism will always be part of a sport official’s occupation. However, organizations may create and in effect deliberately manage the routine presence of such negativity by explicitly supporting their officials.

In creating supportive environments for officials, it is helpful for those charged with doing so to understand the concept of perceived organizational support (POS). POS refers to the degree to which an individual believes that their organization values their contributions, cares about their well-being, and is interested in supporting their socioemotional needs.[17] When an individual perceives that they are well supported by supervisors, being treated fairly, and rewarded for their efforts, POS is high. Conversely, when an individual concludes that support is lacking, they are being treated unfairly, and rewards are absent, POS is low. Importantly, our research has demonstrated that there is a direct correlation between high levels of POS and sport officials’ decisions to remain active in the role regardless of the extent to which they face adversity.[18] Equally important is that with some strategies, dedication to the cause and patience, supportive officiating environments can readily evolve.

We outline the characteristics of these supportive officiating environments below.

1. Create equitable, diverse, and inclusive cultures through organizational governance structures, plans, and policies.

Sport officials are all too often treated as an “afterthought” rather than as a required let alone valued participant within sport.[19] This is driven in part by societal attitudes, but in reality, their participation is also limited by existing barriers in sport organizations. Indeed, all too often existing governance structures and decision-making processes do not allow for representation and or input from the officiating ranks. To counter this, National Sport Organizations (NSOs) and Provincial/Territorial Sport Organizations (PTSOs) in Canada need to ensure that their governing body (e.g., Board of Directors or Executive Committee) includes officiating representatives with voting privileges. Officials should also be included in all strategy and action plan setting meetings to ensure that their perspectives and contributions to the effort are reflected in the resulting documents. By overtly acknowledging and identifying officials as part of their key decision-making processes and activities, established sport organizations may send a strong message of inclusion for this all too often excluded group.

2. Publicly celebrate the accomplishments and contributions of officials.

Another way to create an equitable and inclusive organizational culture for officials is through the development of recognition programs and policies within your organization. This can include recognition through online websites and newsletters, as well as awards at season ending events. Athletes, coaches, and volunteers are routinely celebrated, but the officials tend to receive less attention. Developing recognition programs for your sport officials is a relatively simple but powerful way to let everyone know that officials are valued within your sport.

3. Create robust sport officiating education, training, and mentorship programs and clear performance expectations for officials.

Those aspiring to become officials usually begin the journey through basic educational programs which introduce them to the rules, standards, and technical performance requirements (e.g., correct positioning relative to the field of play, etc.) of officiating in their sport. However, new officials are often then quickly cast into the role and left to learn on the job without the necessary pre-competition training and opportunity to develop confidence in their skills. Some organizations try to offset these challenges by assigning experienced officials to supervise and support new officials during competitions, but this support tends to dwindle over time. Moreover, there is also considerable variation from sport to sport and organization to organization as to the extent to which training sessions (i.e., either at introductory or more advanced levels) are offered, let alone evaluated and thereafter revamped or revised over time.

A commitment to an ongoing cycle of development, planning, implementing, and evaluating for the purposes of improving the quality of training and mentorship programs for officials needs to be adopted as the requirements of being an official today are constantly changing.[20] It’s about much more than just understanding the rules or technical requirements of sport. Today’s officials should be developing competencies related to dispute resolution, conflict management, psychological resilience, and other sport-specific related areas. Such efforts would empower officials to play an active role in creating safer environments for not only themselves, but also for all other participants. Equally important is the development of a culture which promotes continuous (or lifelong) learning and professional development, as is the notion of linking demonstrated skill competencies (e.g., minimum fitness standards) and not just seniority or prior experience to officiating at higher levels.

4. Create educational programs for all sport participants, as well as competition-related arbitrator and ambassador programs .

Some organizations have attempted to reduce the incidence of confrontations between officials, athletes, coaches, and spectators through the introduction of educational programs, as well as competition arbitrators and ambassadors.[21] Educational programming in the form of parental seminars and poster programs are very common, but in the absence of formal program evaluations, it is difficult to understand their efficacy. However, there is every reason to believe that their effectiveness would be improved when used in conjunction with competition-related arbitrator and ambassador programs.

While the officials in sport are tasked with adjudicating the within-competition rules, individuals with prior experience as officials or even dedicated knowledgeable volunteers can be assigned as arbitrators to resolve administrative disputes (e.g., player eligibility) or as ambassadors to resolve spectator behaviour issues. The bounds of an arbitrator’s duties may differ between sports and hence, would need to be defined and made known to all participants prior to the beginning of a competition. The same is true for the role of an ambassador, but their presence would extend beyond the bounds of the competition playing area. Their effectiveness is facilitated by the wearing of easily identifiable colour-coded and/or labelled shirts and having a constant presence at the competition site. Importantly, these roles contribute to the creation of a safer environment for sport officials by reducing both the nature and frequency of potentially confrontational interactions between officials and other sport participants.

5. Adopt zero tolerance policies and corresponding sanctions for all forms of verbal and physical harassment.

Common sense tells us that rules, fines, and other forms of penalties in and of themselves are insufficient to deter some from lobbing threats of verbal or physical violence at officials. Therefore, these alone will not protect or keep officials safe. However, when used in combination with the other strategies outlined above, they should be viewed as an essential part of the overall strategy to keep officials safe.

Conclusion

It will take time and a solid short term commitment from everyone within sport to commit to making sport safer in the long term for officials by actively working to change the culture of sport. This will not be simple or comfortable work. Cultural change is not easily effected but creating a culture that is more inclusive and equitable for officials is the key. It is easiest to begin by modifying the environment one step at a time. Each of the strategies outlined in this chapter should be viewed as just that – a single step – that when introduced in combination with all of the others will lead to cumulative cultural change.

A study by Shawn Eckford on “An Analysis of Minor Hockey Officials and Perceived Organizational Support” examined the extent to which minor hockey officials perceive organizational support (POS) from the minor hockey system, and compared POS among minor hockey officials according to demographics. He surveyed a total of 261 minor hockey officials using the Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (SPOS). His results indicated significant differences according to minor hockey officials’ experience, certification level and extra-role performance. The thesis discusses his finding and makes recommendations as to how administrators can better support these officials.

Future Research

One area for future research is the exploration of implicit cultural biases (e.g. racism, toxic masculinity, homophobia) in sport through the lens of intersectionality. As Cooper and colleagues (2020) note “inequities, inequalities, and discrimination” are barriers to developing an inclusive, welcoming sports environment.

Key Terms

Suggested Assignments

- How inclusive are sports organizations? Choose two (2) or three (3) sports and compare their policies (e.g. guidelines) as well as their practices (e.g. programs, regulations) related to an inclusive sports environment.

- How would you change a toxic sport culture? Select a sport your feel has a toxic culture (e.g. unwelcoming, discriminatory). Explain why you feel it is toxic and identify its main toxic elements. Develop a plan to address them.

- Educational Approaches to an Inclusive Officiating Environment

Option 1: Design a program to educate all sports participants to reduce/eliminate confrontations between athletes, coaches, spectators, and officials. How would you determine if your program is effective?

Option 2: Identify an educational program you think works well to create a positive, safe officiating environment. Describe the program and explain why you think it works.

Figure Descriptions

Figure 19.1 This figure demonstrates why female basketball referees leave the game. At the top of this branching scenario are uncivil behaviours on and off the court. There are four sub-branches beneath this. First is a lack of mutual respect from male counterparts, which is split further into a lack of regard for emotions and feelings by colleagues and supervisors and repetitive, low-intensity, ambiguous violations of respect. The second sub-branch is the perceived inequality of policies, which holds a lateral connection to the first branch. The third sub-branch is a lack of role modelling and mentoring, which branches further into feelings of defenselessness and vulnerability. Gendered abuse is the fourth branch, which has a lateral connection to the third. All four of these branches and sub-branches lead to a perceived lack of community, ultimately causing female referees to leave the game. [return to text]

Sources

Be Soccer. (2018). VAR World Cup status released. Retrieved October 29, 2021, from https://www.besoccer.com/new/var-world-cup-stats-released-488227

Brewer, J. (2021, February 22). Our sports need a healthier version of masculinity and men need to create it. The Washington Post. Retrieved October 26, 2021, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2021/02/22/toxic-masculinity-sports-sexism-don-mcpherson/

Cooper, J. N., Newton, A. C., Klein, M., & Jolly, S. (2020). A call for culturally responsive transformational leadership in college sport: An anti-ism approach for achieving equity and inclusion. Frontiers in Sociology, 5, 1-17. DOI: 10.3389/fsoc.2020.00065

Cuskelly, G., & Hoye, R. (2013). Sports officials’ intention to continue. Sport Management Review, 16(4), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2013.01.003

Dehghansai, N., Lemez, S., Wattie, N., Pinder, R. A., & Baker, J. (2020). Understanding the development of elite parasport athletes using a constraint-led approach: Considerations for coaches and practitioners. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 502981–502981. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.502981

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500-507. DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

Fasting, K. (2015). Assessing the sociology of sport: On sexual harassment research and policy. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(4-5), 437–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214554272

Fink, J. S. (2016). Hiding in plain sight: The embedded nature of sexism in sport. Journal of Sport Management, 30(1), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2015-0278

Leslie, J. P. (1998). The Evangeline league’s man in the blue serge suit: Trials and tribulations. Louisiana History, 39(2), 167–188.

Livingston, L. A., & Forbes, S. L. (2016). Factors contributing to the retention of Canadian amateur sport officials: Motivations, perceived organizational support, and resilience. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 11(3), 342–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954116644061

Livingston, L. A., & Forbes, S. L. (2017). “Just bounce right back up and dust yourself off.”: Participation motivations, resilience, and perceived organizational support amongst amateur baseball umpires. Baseball Research Journal, 46(2), 91-101.

Livingston, L. A., Forbes, S. L., Wattie, N., & Cunningham, I. (2020). Sport officiating: Recruitment, development, and retention. Taylor & Francis Group.

Mano, B. (2018, September). Afterthought. Referee Magazine, 43(9), 4.

Mano, B. (2019, February). See that “train” a coming. Referee Magazine, 44(2), 4.

Parrish, G. (2017, July 28). Adidas shamefully gave LaVar Ball the power to remove a woman from her job. CBS Sports. Retrieved October 27, 2021, from https://www.cbssports.com/college-basketball/news/adidas-shamefully-gave-lavar-ball-the-power-to-remove-a-woman-from-her-job/

Schaeperkoetter, C. C. (2017). Basketball officiating as a gendered arena: An autoethnography. Sport Management Review, 20(1), 128-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2016.05.001

Tietz, S.L. (2018, April). Crisis: In these contentious times, how do officials’ handle difficult situations?. Referee Magazine, 43(4), 22-27.

Tingle, J. K., Warner, S., & Sartore-Baldwin, M. L. (2014). The experience of former women officials and the impact on the sporting community. Sex Roles, 71(1), 7-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0366-8

Voigt, D. Q. (1970). America’s manufactured villain-the baseball umpire. Journal of Popular Culture, 4(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.1970.0401_1.x

Woelfel, R. (2018, April). Replay. Referee Magazine, 43(4), 34-37.

Woelfel, R. (2018, May). Money ball. Referee Magazine, 43(5), 58-63.

Woelfel, R. (2020, September). Harassment halt. Referee Magazine, 45(9), 38-41.

- Livingston et al., 2020. ↵

- Livingston & Forbes, 2017. ↵

- Cuskelly & Hoye, 2013. ↵

- Woelfel, 2020. ↵

- e.g., Leslie, 1998; Voigt, 1970. ↵

- Woelfel, 2018, April. ↵

- Be Soccer, 2018. ↵

- Tietz, 2018. ↵

- e.g., Fasting, 2015; Tingle et al., 2014. ↵

- Woelfel, 2020. ↵

- Fink, 2016. ↵

- Tingle et al., 2014. ↵

- Parrish, 2017. ↵

- Woelfel, 2020, p. 39. ↵

- Fink, 2016. ↵

- Dehghansai et al., 2020. ↵

- Eisenberger et al., 1986. ↵

- Livingston & Forbes, 2016. ↵

- Mano, 2018, p. 4. ↵

- Mano, 2019. ↵

- Woelfel, 2018, May. ↵

The degree to which an individual generally believes their organization values their contributions, cares about their well-being, and is interested in supporting their socioeconomic needs.

Based on shared values, beliefs, etc., an inclusive culture acknowledges, respects, and values diversity.

Reflects a refusal to accept inappropriate, prohibited, and undesirable behaviour (e.g. words, actions).

In Practice:

In Practice:

Self-Reflection

Self-Reflection