16 Relational Risk Management Planning: From Theory to Practice

Michael Van Bussel

Kirsty Spence

Themes

Operationalizing relational risk management concepts

Utilizing the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS) to integrate relational risk management into sport organizations

How relational risk management plans integrate into codes of conduct in sport organizations

Learning Objectives

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

LO1 Identify the importance of athlete-centred care;

LO2 Distinguish the operationalization of relational risk management planning;

LO3 Recognize how safe sport can be integrated into organizational policy and practice.

Overview

In the first edition chapter on relational risk management, the various aspects of this concept were highlighted including contextual sensitivity, responsiveness and trust, and consequences of choice. It is through these various aspects that athletic administrators can begin to build sport organizations that focus on athlete-centred care. Utilizing aspects of Relational Risk Management may assist all sport constituents (i.e., athletes, coaches, administrators) in formalizing codes of conduct within organizational rules, such as the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS). Likewise, educating all parties, from athletes to volunteers and from coaches to administrators, about safe sport is imperative to reduce occurrences maltreatment. From national sport organizations to local sport bodies, it is essential that these organizational leaders look for ways to avoid opportunities for maltreatment to occur, to build confidence in modes of protection that are in place, and address maltreatment situations swiftly and directly, should they occur.

Key Dates

From horrific accounts of Dr. Larry Nassar becoming public in August of 2016 and his abuse of over 500 gymnastic athletes at Michigan State University and USA Gymnastics to the April 2024 settlement of $138.7 million dollars by Federal Bureau of Investigations for its failure to properly handle of the Nassar investigation, we see breakdowns in the ability of sport organizations and enforcement agencies to protect athletes in their greatest time of need.[1] In Canada, sport organizations have also abdicated responsibility when it comes to protecting athletes. For example, Alpine Canada, Hockey Canada, Soccer Canada, and Water Polo Canada are sport organizations which have all recently received headlining attention for incidents of maltreatment within their organizations.[2]

In 2019, the Canadian federal, provincial, and territorial ministries responsible for sport came together, through the Red Deer Declaration, to acknowledge the importance of safe sport, stating “all Canadians have the right to participate in sport in an environment that is safe, welcoming, inclusive, ethical and respectful, and one that protects the dignity, rights and health of all participants.”[3]

More specific to safe sport, the representatives at this meeting stated it was their responsibility to work together to implement “a collaborative intergovernmental approach, with better harmonized commitments, mechanisms, principles, and actions to address harassment, abuse, and discrimination in sport in the areas of awareness, policy, prevention, reporting, management, and monitoring.”[4]

As a result of these meetings, a partnership formed between AthletesCAN, the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport, the Coaching Association of Canada (CAC), University of Toronto researchers, and the Government of Canada. These partners met during several organized summits and talked about safe sport issues.[5] From this, the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS) was developed that codified safe sport behaviours and remedies for transgression. While the UCCMS was first published by the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES) in 2019, Version 6 was published by the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC) in 2022 and was mandated for implementation in all national sport organizations by November 30, 2022.[6]

The UCCMS guides national, provincial and local sport organizations in their protection of athletes and includes guidance for remedies, should incidents occur.

The basic structure of the UCCMS includes:

- Purpose

- General Principles and Commitment

- Objectives

- Scope of Application

- Prohibited Behaviours

- Other Proceedings and Recognition of Sanctions

- Range of Possible Sanctions

- Public Disclosure[7]

Sections of the UCCMS are next described, in relation to how they integrate with the Relational Risk Management framework and plan.

Relational Risk Management

Also in this previous edition, “Relational Risk Management” was defined as the process through which athletes, coaches and administrators proactively identify relational risks; this is a process of finding ways to enable positive communication and to address issues in a timely manner, should they arise.[10] Relational Risk Management behaviours are present in the UCCMS as well, and include reporting incidents, sanctioning of transgressors, the consequences of failure to report, retaliation, and the timeliness of action.[11]

Both Relational Risk Management and the UCCMS position the athlete at the centre of the risk management process. By empowering athletes and placing at them at the centre of focus, all stakeholders can be engaged in the safe sport process and protection for all involved with sport can be further ensured.

The power inherent with a coach’s position cannot be understated. At the risk of sounding cliché, as coaches are placed in positions of power, they have great responsibility. Situations that are characterized by dominant personalities, power imbalances, and high-pressure expectations are rife with opportunities for coaches to abuse their power. Indeed, given the balance of power between an athlete and a coach is unequal, such imbalance can lead to increased opportunities for abuse.[12]

The focus on creating an athlete-centred environment aligns with the heart of relational risk management (RRM), as RRM is about developing, maintaining and preserving relationships developed through sport. With an ethic of care, the relationships that exist in sport are prioritized, the hierarchies that have existed in the past are reconsidered and the co-existence of all constituents are re-envisioned in the future.[13] Behaviour such as physical and psychological abuse, sexual misconduct, neglect and retribution do much to undermine the fabric of sport. To support the notion of athlete-centred sport, athletes must establish influence over their environment and become participants in the process, rather than remaining as passengers in the experience.

In the News:

Call to Safe Sport Action

“Coaches Association of Ontario inaugural coaching report finds coaches play a vital role in sport, but only half are trained” by Coaches Association of Ontario, Cision Canada, November 30, 2023.

With the release of the Coaches Association of Ontario (CAO) 2023 study, it was revealed that only 58% of coaches completed any type of training prior to their interactions with athletes. Of those who engage in training, over 70% coaches are required to pay out of pocket for training and certification in their sport. As Jeremy Cross, the Executive Director of the CAO stated:

Coaches play such a significant role in shaping the environment and experience for everyone participating. Research shows that a positive coach is one of the most influential people in a young person’s life. And with so many Ontarians coaching in their communities, it is vital that the training and supports our coaches need are there to create the best possible experience.[14]

What safe sport education resources are in place for our coaches?

Athlete-Centred Care Revisited

With the evolution of theory to practice, it is important to revisit the three distinct areas of athlete-centred care:

- Contextual sensitivity

- Responsiveness and trust

- Consequence of choice

These three areas impact the promotion of safe sport and will ultimately allow athletes, coaches and administrators to use the proper tools for to prevent and remedy situations of maltreatment. The three distinct areas of athlete-centred care are next detailed.

Contextual Sensitivity. This aspect of athlete-centered care considers the unique needs of each and every athlete in relation to their sport and the environmental influences that may impact decision making and approaches to athlete interaction. Possessing an awareness of the sport milieu and considering past and present social and political pressures provides a more wholistic picture of what may impact the athlete.[15]

Indeed, knowing that equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) education is evolving is an important additional component to understanding contextual sensitivity. As Peers et al. (2023) explained, “EDI policies have been implemented as a way for Canadian sport to respond to historical and contemporary social conditions of significant inequity, exclusion, harm, and injustice.”[16]

Policy itself is not a panacea to this issue however, as these authors argued that “exclusion in sport is underpinned and (re)created by structural mechanisms such as power imbalance, cultural norms, and economically driven policies, wherein dominant groups maintain control of the management and organisation of sport.”[17]

Creating a Relational Risk Management approach that includes contextual sensitivity refocuses all on the relationship and allows for better use of policies for sound decision-making and inclusion. Indeed, the use of contextual sensitivity promotes the building of a solid foundation upon which the athlete experience is based and from which the coach-athlete-administrator relationship may grow.

Responsiveness and Trust. The importance of action in the promotion of safe sport is critical to building and maintaining responsiveness and trust. The UCCMS, by defining various forms of maltreatment and outlining various responses and sanctions to address transgressions, promotes responsiveness by including sections for the promotion of hearings into incidents of maltreatment, possible sanctions, and sanctioning considerations.[18]

The UCCMS also provides guidelines on how to identify maltreatment so athletes may identify instances of abuse, coaches may be aware of what is deemed acceptable, and administrators have clear definitions for what actions to take. Indeed, it is a reciprocal relationship through which athletes, coaches and administrators work together to create an environment of trust. This environment of trust and respect can grow and develop when, “coaches and others in positions of power are required to recognize and respond to the self-identified needs and concerns of athletes.”[19]

Consequences of Choice. The distinct area of consequences of choice has a proactive, critical reflective, and action-oriented quality to promoting safe sport. From a proactive perspective, the reflection that occurs in the consequences of choice phase looks to identify actions and behaviours that have harmful effects on athletes. Having this understanding of past actions and decisions allows coaches to avoid harmful actions before they occur.

From a critical reflective perspective, utilizing consequences of choice allows athletes, coaches, and administrators to reflect on their actions, or lack thereof, when considering the promotion of safety and enjoyment in sport.

Finally, this phase calls all parties to act, if transgressions occur, to properly address instances of maltreatment with recourse (i.e., fines, suspensions and terminations) and effect so future instances do not reoccur. Kirby et al. (2000) outlined the consequences of choice “raise awareness of how self-esteem, self-confidence, and self-respect can be nurtured or alternatively destroyed in relationships of trust such as those between coaches and athletes.”[20]

We challenge coaches and sport administrators in Canada and abroad:

- To consider the supports for athletes that their organizations have to promote safe sport;

- To continuously evaluate the supports in place to measure their impact and effect on athletes and the organization;

- To question how we can be leaders and support others in the protection of athletes in our communities.

The three distinct areas of Athlete Centred Care, including Contextual Sensitivity, Responsiveness and Trust, and Consequences of Choice provide a strong framework from which we can create safe sport policy and coaching codes of conduct. Through understanding and enacting these three areas, we propose sport managers, coaches, athletes can connect with safe sport education, maltreatment prevention, and organizational action.

Case Study:

Case Study:

Centre for Sport Capacity

In a follow up to the very successful Athletes First: The Promotion of Safe Sport in Canada, the Centre for Sport Capacity (CSC) at Brock University hosted a second safe sport series 2023 Safe Sport Forum: Can Sport Regulate Itself? in November of 2023. At this forum, former athletes, legal experts and academics specializing in safe sport research discussed topics of self-regulation in sport, legal perspectives regarding regulation, athletes’ perspective in the utilization of third-party safe sport mechanisms, and provincial and territorial perspectives on the development of safe sport protocols.

Dr. Hilary Findlay talked about the important conversations that are happening through the forum, stating “We need a big rethink of how sport is governed to fully address the issue. Some of this work has begun both at the provincial/territorial level and national level of sport and will be highlighted as part of the forum’s agenda.”[21]

Video 16.1 Towards a Safer Sport Culture: Panel – Dr. Julie Stevens, Dr. Hilary Findlay, Allison Forsyth – 2023 Safe Sport Forum

Video provided by Brock University Centre for Sport Capacity. Used with permission. [Transcript]

Relational Risk Management Plan

In this section, the components of a relational risk management plan are next discussed. This discussion is not meant to be a comprehensive list of elements, but rather a flexible template that may provide suggestions for organizations in designing their own relational risk management plan. Integrated into the plan are elements and themes from the National Coaching Certification Program Code of Ethics and the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and address Maltreatment in Sport.[22]

Contextual Sensitivity

It is critically important for coaches and administrators to understand the needs of athletes and to recognize the demands of their sport. Regarding the athlete, contextual sensitivity should be a wholistic view that takes into consideration the impacts of an athletes’ physical, mental and emotional health in order to provide a safe and enjoyable environment. Below are factors that should be considered when enacting contextual sensitivity elements.

Athlete responsibility. Athletes must be involved in the relational risk conversation, as they are an essential to recognizing relational risks and communicating their concerns about such risks to coaches and administrators. Another factor to consider is athletes’ completion of coaching evaluations, as these data collection points are important tools for administrators in their performance evaluation of coaches. Athletes must also feel free to ask questions and approach coaches and administrators without any fear of punishment or retribution.

Administrative responsibility. Athletic administrators must be engaged in and aware of what is happening in their organization. If administrators are present and visible at games, practices and events on a consistent basis they will better understand what is happening in their organizations. From a safe sport perspective, athletic administrators must be available to receive and deal with any concerns that may arise. In addition, they should engage in regular cycles of coaching performance evaluations, understanding that such coaching effectiveness data can be used to improve the athlete experience.

Coach responsibility. Coaches’ understanding of contextual sensitivity is crucial. Specifically, coaches’ understanding of both their athletes and their sport is a first step in minimizing maltreatment. Moreover, coaches’ use of multiple modes of communication and feedback should eliminate elements such as neglect, as highlighted in the UCCMS. In addition, any information that athletes entrust to their coaches should be treated by the coach as confidential and handled with the utmost privacy and respect. Ultimately, all coaches should practice continued professional development in the areas of athlete safety and coaching effectiveness.

Responsiveness and Trust

The athlete should be the central focus of coaches and administrators. Providing an athlete-centred environment protects athletes and reduces the potential for maltreatment. Moreover, when an athlete feels safe, an ecosystem within which trust can grow and flourish is created. The following items should be prioritized when addressing responsiveness and trust.

Discrimination-Free Sport. It should be the goal of any sport program to eradicate any form of discrimination, from an organization, from a coach, or from a participant. Discrimination must not be tolerated in any form. Coaches and administrators must be aware of equity, diversity, and inclusion principles. A significant step to eliminating discriminatory maltreatment is the administrators’, coaches’ and athletes’ self awareness of discriminatory practices.

Physical Abuse Free Sport. Unwanted physical contact of any kind can immediately destroy any degree of trust that exists between a coach and an athlete. Physical abuse can be as blatant as a punch or kick or as subtle as using exercise as punishment. Even forcing athletes to play while injured or concussed can be deemed as physical abuse. Enforcement of significant sanctions must be applied to cases of physical abuse.

Psychological Abuse Free Sport. Use of abusive language by coaches or administrators can significantly undermine their authority with athletes and others in the sport context. More importantly, psychological abuse can have significantly negative impact on an athlete’s well-being and confidence. Conversely, a coach or administrator’s encouragement, support and positive feedback can help an athlete grow through their experience. Such sport leaders must continually monitor their own messages and those of individuals connected to their programs. Psychological maltreatment, bullying behaviour and mental manipulation through approaches like neglect should not be tolerated.

Sexual Abuse Free Sport. Sexual abuse, harassment, or grooming types of behaviour should never be tolerated by any sport organization. Sexual misconduct is one of the most significant abuses of power and abdications of responsibility any coach or administrator can make. In addition, sexual relationships with athletes, consensual or not, have life-altering impacts for all parties involved. Sport organizations must ensure all constituents’ sexual safety at all times.

Honesty. Coaches who are open and honest significantly contribute to building trusting relationships within their organizations. For coaches, eliminating mixed messaging regarding performance (e.g., an athlete’s role, or playing time) is essential when developing trust within their team. If coaches make promises to athletes, supervisors should ensure such promises are realized. Providing honest constructive criticism to athletes may help them improve their performance and confidence.

Respect. At the centre of an athlete-centred program is the key concept of demonstrating respect for all. Maintaining a relationship of mutual trust between coaches and athletes must be foundationally based on respect. Allowing athletes to be part of the Relational Risk Management process and empowering their decision-making is an important step in nurturing such respect.

Consequences of Choice

When reflecting on the options that are made and the outcomes that are presented, athletes, coaches, and administrators all evaluate their consequences of choice. Ultimately, such evaluations may help athletes, coaches, and administrators make future choices, to improve protections for athletes. The following items will help in the development of consequence of choice for those involved in sport.

Engagement. After moving through the process of evaluating consequences of choice, the process of understanding the contextual sensitivity of athletes is emphasized even more. It is important to engage athletes in goal and rule setting processes, thus being responsive to their needs and further building trust. Granting athletes opportunities to engage in goal setting and rule formation is a definite part of fostering an athlete-centred environment. Ultimately, the engagement coaches, athletes and administrators in the continued development of the sport experience is something that should be present in reflection on the consequences of choice by all parties.

Feedback and Emotion. Coaches must be aware that athletes may feel uncomfortable to approach them for advice and feedback. Moreover, coaches are advised to understand that different athletes need different types of feedback. Utilizing a variety of feedback modes (e.g., formal and informal meetings, video, statistics) may allow coaches to meet and reach the individual players on their team, based on their diverse needs. In addition, as sport experiences often evoke emotional responses, coaches should provide athletes with the ability to express their emotions in a safe environment. For example, coaches using the ‘Rule of Two’ (e.g., two adults present) is one way to ensure that communication can be open, witnessed and supported.

Encouragement. An athlete-centred sport environment is one that is characterized by positivity, enthusiasm, and passion for all involved. Wholistic development of the athlete-as-person should be central in connection to an athlete’s athletic performance and achievements.

Empowerment. It is critical that the athlete be engaged in developing their own sporting environment and be able to make decisions that will impact their experience. Providing athletes the space to establish their own contextual sensitivity, responsiveness and trust, and consequences of choice will create an environment of accountability.

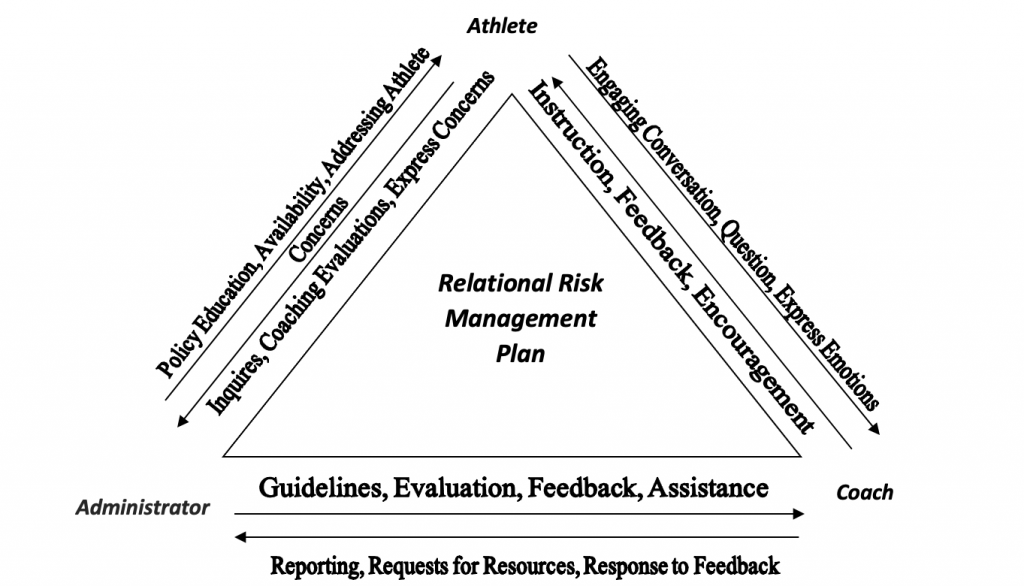

Everyone has a responsibility to promote safe sport. It is essential that the administrator, the coach, and the athlete collaborate to ensure Relational Risk Management Plan effectiveness. Should any of these parties disengage in the procedure, a breakdown in the process may occur. As the Relational Risk Management Plan rests in the middle the Relational Risk Management Model, it is important for all three parties to work together to provide a safe and engaging sport environment for all.

Figure 16.1 Relational Risk Management Plan

In conclusion, this chapter highlights several important tools that may be used in the promotion of safe sport. Relational risk, relational risk management and athlete-centred care concepts were revisited. With these concepts in place, a Relational Risk Management plan was highlighted, as were the three distinct tools of: contextual sensitivity, responsiveness and trust, and consequences of choice to operationalize various aspects of codes such as the UCCMS. Indeed, these tools may help organizations connect with constituents to promote an environment of athlete-centred care.

Self-Reflection

-

You are the coaching director of a youth soccer club. You have been directed to ensure all coaches have additional training in safe sport protocols beyond their “Respect in Sport” online module. What resources do you direct them to?

-

The UCCMS is an important document in the promotion of safe sport at the national sport organizational level. How do we ensure that it is also impactful at the community sport level?

-

You have been approached by an athlete that has been maltreated. What are your responsibilities? How does the athlete access the third-party adjudication services?

Further Research

A knowledge gap exists regarding the impact of safe sport educational resources. It will be important to see what safe sport resources exist and their impact on athletes, coaches, and administrators. It will be equally important to determine what is being done on a global scale regarding safe sport education. Understanding the intricacies of safe sport education will allow for process improvement of this important educational endeavour.

Key Terms

Suggested Assignments

- Reflective Practice: If you have worked in the role of coach or athletic administrator, reflect on your experience over the past few years. What have you done to create a safe sport environment for your athletes? What have you done to create an athlete-centred sporting experience?

- Compare and Contrast: Select a Canadian national sport organization (NSO) and a similar sport organization in a different country. What supports are in place for coaching development around safe sport? Compare the discussion of safe sport promotion between these sport organizations. How comparable are these sport organizations in relationship to their depth and breadth?

Figure Descriptions

Figure 16.1 This figure demonstrates the relational risk management plan, shaped in a triangle with athlete, coach and administrator at its three points. From the athlete to the coach are engaging conversation, question, and express emotions, and from the coach back to the athlete are instruction, feedback, and encouragement. From the coach to the administrator are reporting, requests for resources, and response to feedback. From the administrator back to the coach are guidelines, evaluation, feedback and assistance. From the administrator to the athlete policy education, availability, and addressing athlete concerns. From the athlete back to the administrator are inquires, coaching evaluations, and express concerns. [return to text]

Sources

Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat (2019). RED DEER DECLARATION – For the Prevention of Harassment, Abuse and Discrimination in Sport. Ottawa, ON. https://scics.ca/en/product-produit/red-deer-declaration-for-the-prevention-of-harassment-abuse-and-discrimination-in-sport/

Coaches Association of Ontario. (2023). Coaches Association of Ontario inaugural coaching report finds coaches play a vital role in sport, but only half are trained. CISION. https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/coaches-association-of-ontario-inaugural-coaching-report-finds-coaches-play-a-vital-role-in-sport-but-only-half-are-trained-801010317.html

Davidson, N. (2022, July 28). Review says Canada Soccer mishandled sexual assault allegations against coach. CBC Sports. https://www.cbc.ca/sports/soccer/canada-soccer-mishandles-sexual-harassment-allegations-1.6534967.

Dimmock, G. (2023, December 13). Top athlete sues Water Polo Canada for abuse: lawsuit. Ottawa Citizen. https://www.cbc.ca/sports/soccer/canada-soccer-mishandles-sexual-harassment-allegations-1.6534967.

Heroux, D. (2023, October 3). 25 years after being sexually abused by coach, Olympian Allison Forsyth settles lawsuit with Alpine Canada. CBC Sports. https://www.cbc.ca/sports/safe-sport-allison-forsyth-alpine-canada-1.6984863.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kirby, S., Greaves, L., & Hankivsky, O. (2000). The dome of silence: Sexual harassment and abuse in sport. Halifax: Fernwood.

National Coaching Certification Program (2020). The NCCP Code of Ethics. Coaching Association Of Canada, Ottawa. https://coach.ca/sites/default/files/2020-03/NCCP_Code_of_Ethics_2020_EN.pdf

Peers, D., Joseph, J., Chen, C., McGuire-Adams, T., Fawaz, N. V., Tink, L., Eales, L., Bridel, W. Hamdon, E., Carey, A., & Hall, L. (2023). An intersectional Foucauldian analysis of Canadian national sport organisations’ ‘equity, diversity, and inclusion’ (EDI) policies and the reinscribing of injustice. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 15(2), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2023.2183975

Pesta, A. (2019, July 18). An Early Survivor of Larry Nassar’s Abuse Speaks Out For the First Time. TIME. https://time.com/5629228/larry-nassar-victim-speaks-out/.

Shilton, K. (2024, February 5). Hockey Canada sexual assault scandal: Timeline of events. ESPN. https://www.espn.com/nhl/story/_/id/39436540/hockey-canada-sexual-assault-case-scandal-news-updates.

Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (2022). Universal code of conduct to prevent and address maltreatment in sport. Ottawa, ON. https://sportintegritycommissioner.ca/files/UCCMS-v6.0-20220531.pdf

Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (April 2024). UCCMS History and Background. Ottawa, ON. https://sportintegritycommissioner.ca/uccms-history

Titone, J. (2023). Safe sport in Canada: Brock forum to discuss crisis of athlete abuse, Maltreatment. Brock University, St. Catharines, ON. https://brocku.ca/brock-news/2023/11/safe-sport-in-canada-brock-forum-to-discuss-crisis-of-athlete-abuse-maltreatment/

Van Bussel, M., & Spence, K. (2022). Chapter 15: Relational risk management and the promotion of safe sport. In J. Stevens (Eds.), Safe Sport: Critical Issues and Practices. (pp. 206-220). E-Campus Ontario.

White, E. (2024, April 23). U.S. government agrees to $138.7M US settlement over FBI’s botching of Larry Nassar allegations. CBC Sports. https://www.cbc.ca/sports/olympics/summer/gymnastics/gymnastics-larry-nassar-settlement-fbi-1.7182242#:~:text=Gymnastics-,U.S.%20government%20agrees%20to%20%24138.7M%20US%20settlement%20over%20FBI’s,Nassar%20in%202015%20and%202016.

- Pesta, 2019; White, 2024 ↵

- Heroux, 2023; Shilton, 2024; Davidson, 2022; Dimmock, 2023 ↵

- CICS, 2019, p. 1 ↵

- CICS, 2019, p. 1 ↵

- SDRCC, April 2024 ↵

- SDRCC, 2022 ↵

- SDRCC, 2022, p.2 ↵

- Van Bussel & Spence, 2022 ↵

- SDRCC, 2022 ↵

- Van Bussel & Spence, 2022 ↵

- SDRCC, 2022 ↵

- Kirby et al, 2000 ↵

- Gilligan, 1982 ↵

- CAO, 2023 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000 ↵

- Peers et al., 2023, p. 194 ↵

- Peers et al., 2023, p. 194 ↵

- SDRCC, 2022 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 145 ↵

- Kirby et al., 2000, p. 145 ↵

- Titone, 2023, p. 1 ↵

- NCCP 2023; SDRCC 2022 ↵

- Van Bussel & Spence, 2022 ↵

- SDRCC 2022 ↵

- U of G, 2024 ↵

- U of G, 2024 ↵