119

When preparing to share our work with others we must decide what to share, with whom to share it, and in what format(s) to share it. In this section, we will consider the former two aspects of sharing our work. In the sections that follow, we will consider the various formats and mechanisms through which social scientists might share their work.

Sharing it all: the good, the bad, and the ugly

Because conducting sociological research is a scholarly pursuit, and sociological researchers generally aim to reach a true understanding of social processes, it is crucial that we share all aspects of our research—the good, the bad, and the ugly. Doing so helps to ensure that others will understand, be able to build upon, and effectively critique, our work. It is important to share all aspects of our work for ethical reasons, and for the purpose of replication. In preparing to share your work with others, and in order to meet your ethical obligations as a sociological researcher, challenge yourself to answer the following questions:

- Why did I conduct this research?

- How did I conduct this research?

- For whom did I conduct this research?

- What conclusions can I reasonably draw from this research?

- Knowing what I know now, what would I do differently?

- How could this research be improved?

- What questions, if any, was I unable to answer fully, partially, or not at all?

Understanding why you conducted your research will help you to be honest with yourself and your readers about your own personal interest, investments, or biases with respect to the work. This means being honest about your data collection methods, sample and sampling strategy, and analytic strategy. The third question in the list above is designed to help you articulate who the major stakeholders are in your research. Of course, the researcher is a stakeholder. Additional stakeholders might include funders, research participants, or others who share something in common with your research subjects (e.g., members of a community where you conducted research, or members of the same social group, such as parents or athletes, upon whom you conducted your research). Professors for whom you conducted research as part of a class project might be stakeholders, as might employers for whom you conducted research. We’ll revisit the concept of stakeholders in Chapter 17 “Research Methods in the Real World”.

The fourth question should help you think about the major strengths of your work. Finally, the last three questions are designed to make you think about potential weaknesses in your work and how future research might build from or improve upon your work.

Knowing your audience

Once you are able to articulate what to share, you must decide with whom to share it. Certainly, the most obvious candidates with whom you will share your work are other social scientists. If you are conducting research for a class project, your main “audience” will probably be your professor. Perhaps you will also share your work with other students in the class. Other potential audiences include stakeholders, reporters and other media representatives, policy makers, and members of the public more generally. While you would never alter your actual findings for different audiences, understanding who your audience is will help you frame your research in a way that is most meaningful to that audience.

Presenting your research

Presenting your research is an excellent way to get feedback on your work. Professional sociologists often make presentations to their peers, as a way to prepare for more formally writing up and eventually publishing their work. Presentations might be formal talks, either as part of a panel at a professional conference or to some other group of peers or other interested parties; less formal roundtable discussions (another common professional conference format); or posters that are displayed in some specially designated area. We’ll look at all three presentation formats here.

When preparing a formal talk or presentation, it is very important to get details well in advance about how long your presentation is expected to last and whether any visual aids such as video or PowerPoint slides are expected by your audience. At conferences, the typical formal talk is usually expected to last between 15 and 20 minutes. While this may sound like a torturously lengthy amount of time, you will be amazed the first time you present formally by how easily time can fly. Once a researcher gets into the groove of talking about something for which they have a passion, they commonly become so engrossed in it that they forget to watch the clock and end up going over the allotted time. To avoid this all-too-common occurrence, it is crucial that you repeatedly practice your presentation in advance, and time yourself. Another tip is to keep a watch or other means of checking the time at your fingertips to keep an eye on the time.

One stumbling block in formal presentations of research work is setting up the study or problem the research addresses. Keep in mind that with limited time, audience members will be more interested to hear about your original work than to hear you cite a long list of previous studies to introduce your own research. While in scholarly written reports of your work you must discuss the studies that have come before yours, in a presentation of your work the key is to use what precious time you have to highlight your work. Whatever you do in your formal presentation, do not read your paper verbatim. Nothing will bore an audience more quickly than that. Highlight only the key points of your study. These generally include your research question, your methodological approach, your major findings, and a few final takeaways.

In less formal roundtable presentations of your work, the aim is usually to help stimulate a conversation about a topic. The time you are given to present may be slightly shorter than for a formal presentation, and you will also be expected to participate in the conversation that follows all presenters’ talks. Roundtables can be especially useful when your research is in the earlier stages of development.

Perhaps you have conducted a pilot study and you would like to talk through some of your findings and get some ideas about where to take the study next. A roundtable is an excellent place to get some suggestions and also get a preview of the objections reviewers may raise with respect to your conclusions or your approach to the work. Roundtables are also great places to network and meet other scholars who share a common interest with you.

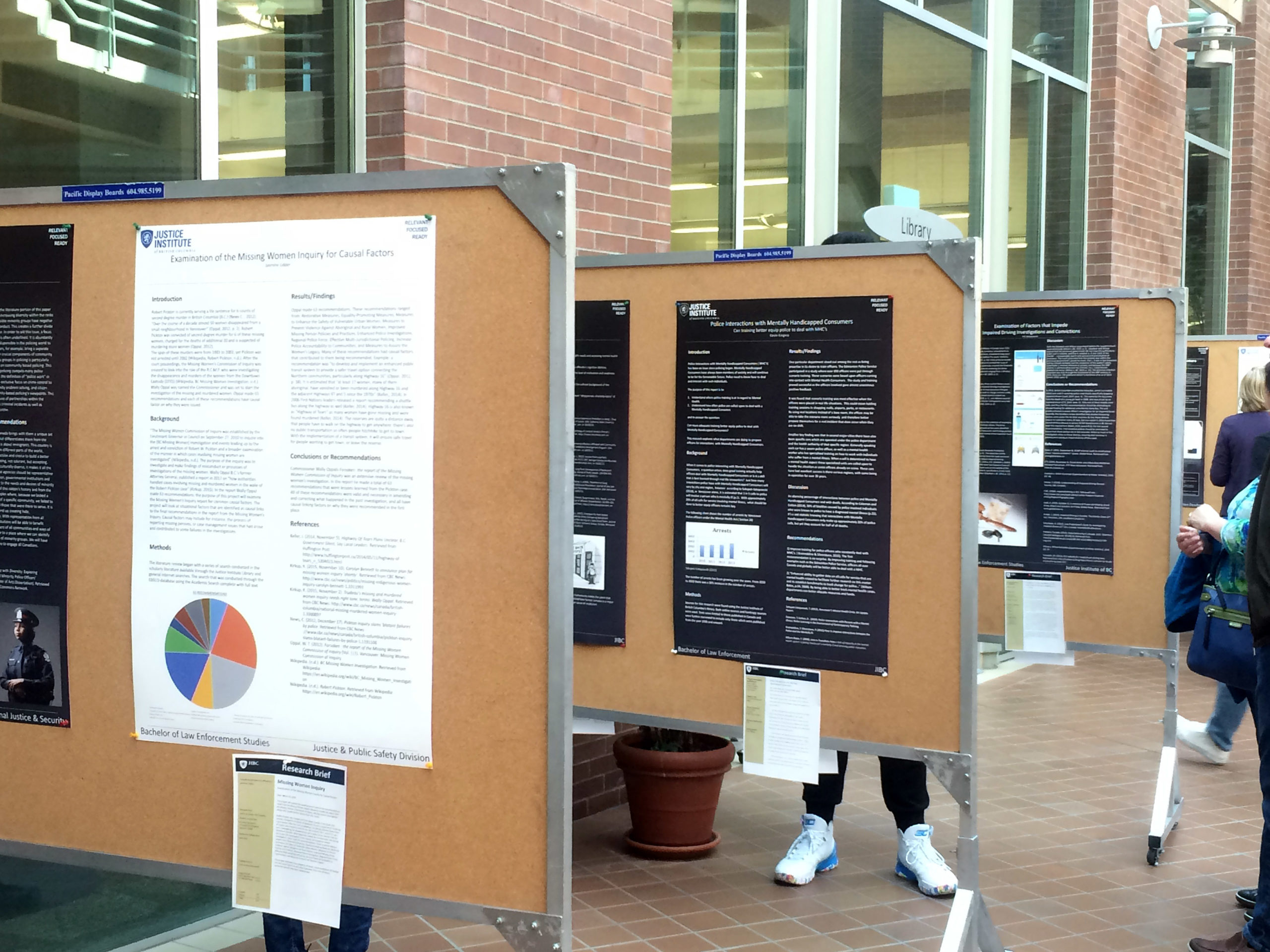

Finally, in a poster presentation you visually represent your work. Just as you would not read a paper verbatim in a formal presentation, avoid at all costs printing and pasting your paper onto a poster board. Instead, think about how to tell the “story” of your work in graphs, charts, tables, and other images. Bulleted points are also fine, as long as the poster is not so wordy that it would be difficult for someone walking by very slowly to grasp your major argument and findings. Posters, like roundtables, can be quite helpful at the early stages of a research project because they are designed to encourage the audience to engage you in conversation about your research. Do not feel that you must share every detail of your work in a poster; the point is to share highlights and then converse with your audience to get their feedback, hear their questions, and provide additional details about your research.