1. Understanding Research Skills

What are Research Skills?

Before we can teach research skills to students, we need to have a clear idea of what research skills are. But of course, to understand what we mean by ‘research skills’, we first need to wrestle with what we mean by ‘research’ itself.

What do you think of when you hear the term ‘research’?

- ‘Googling’ symptoms or medical treatments you or a family member are experiencing?

- Comparing vehicle specifications to help you determine which vehicle to purchase?

- Conducting a S.W.O.T. analysis for a business plan?

- Administering a lab experiment?

- Designing surveys and then analyzing the responses?

- Receiving the teachings of an Indigenous elder or traditional knowledge keeper?

- Compiling and analyzing qualitative or quantitative data?

- All of the above?

- None of the above?

We engage in many types of research every day – each within specific contexts and with unique goals and strategies.

In this guide, we’ll use the term ‘research’ to refer specifically to source-based research activities for academic purposes. In other words, the type of research required to complete typical research assignments or research projects offered in a post-secondary course of study.

Searching for Information

Research assignments are a unique type of assessment that requires students to find, select, and synthesize information from a variety of sources. The required information can come in many formats (e.g., oral, print, digital) and from a variety of different types of sources (e.g., webpages, magazine or newspaper articles, books, multi-media presentations, images, elders or knowledge keepers, scholarly journals).

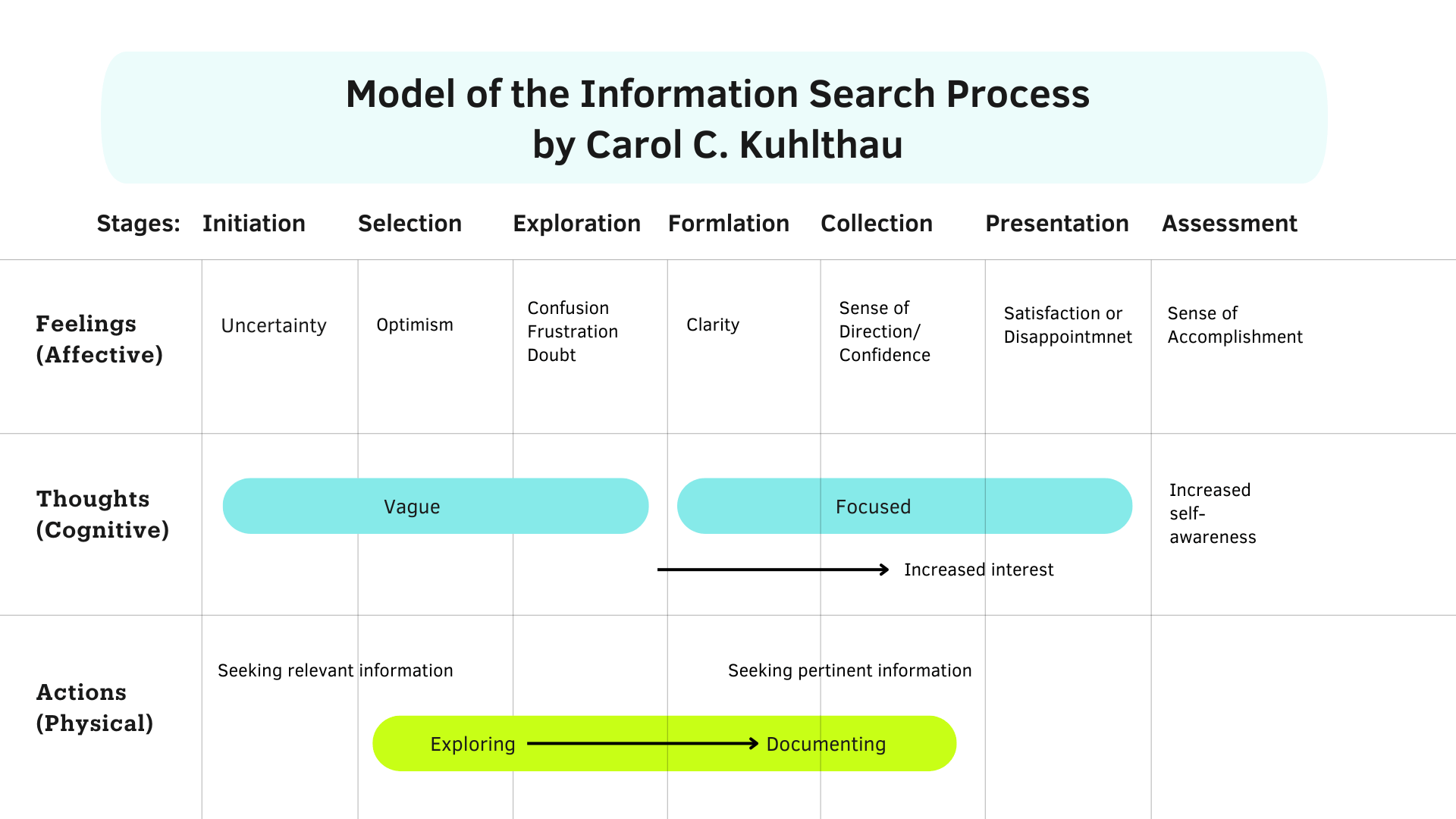

The Information Search Process (ISP), developed and refined by Carol Kuhlthau over two decades of empirical studies, provides a helpful model for understanding the experiences and competencies required for this type of assessment. According to ISP, information seeking takes place over six stages: task initiation, selection, exploration, focus formulation, collection, and presentation. As shown in the figure below, the ISP incorporates three domains of experience: the affective (feelings) the cognitive (thoughts) and the physical (actions).

Figure 1: Model of the Information Search Process

NOTE: The Model of the Information Search Process by Carol C. Kuhlthau. Rutgers School of Communication and Information, (n.d.). http://wp.comminfo.rutgers.edu/ckuhlthau/information-search-process

As students move from exploring to documenting the information, they experience uncertainty, optimism, then confusion, frustration, and doubt, before gaining clarity and a sense of direction and confidence. While their thoughts begin as vague, they become more focused and develop increased interest in the information as the search progresses. The completion of the activity generally elicits a sense of accomplishment and increased self-awareness.

While this model might suggest that research is a linear process, in practice returning to previous stages before progressing further in the process is commonly required.

Problematizing Research Competencies

In some ways, a simple list of research tasks as described above can obscure the complexity of these tasks and the complexity of the information landscape students must navigate within in order to complete a research activity.

Let’s take the initiation stage as a simple example. Identifying a research need or research topic can often be a very difficult task in this stage of the ISP. Consider what students need to know to formulate a research-able topic. For example, students would need to:

- Have sufficient disciplinary knowledge to identify their own gaps in knowledge, understand the depth of research in the field, or draw new connections between core concepts.

- Understand what type of evidence is required to make sound conclusions, whether such evidence would likely be available for the topic, and where one might find such evidence.

- Know how to write questions with clarity and precision of language to help guide the research project effectively.

- Know how to explore background information to test out different topics and refine the research question and thesis.

You get the point. Behind each task for any given research activity is a longer list of competencies and knowledge practices required to be successful, often involving a sophisticated understanding of information, how it is produced and shared and by whom.

These complex research competencies and knowledge practices are often studied under the field of information literacy.