29 Participant Observation

Allison Hurst

Introduction

Although there are many possible forms of data collection in the qualitative researcher’s toolkit, the two predominant forms are interviewing and observing. This chapter and the following chapter explore observational data collection. While most observers also include interviewing, many interviewers do not also include observation. It takes some special skills and a certain confidence to be a successful observer. There is also a rich tradition of what I am going to call “deep ethnography” that will be covered in chapter 14. In this chapter, we tackle the basics of observational data collection.

What is Participant Observation?

While interviewing helps us understand how people make sense of their worlds, observing them helps us understand how they act and behave. Sometimes, these actions and behaviors belie what people think or say about their beliefs and values and practices. For example, a person can tell you they would never racially discriminate, but observing how they actually interact with racialized others might undercut those statements. This is not always about dishonesty. Most of us tend to act differently than we think we do or think we should. That is part of being human. If you are interested in what people say and believe, interviewing is a useful technique for data collection. If you are interested in how people act and behave, observing them is essential. And if you want to know both, particularly how thinking/believing and acting/behaving complement or contradict each other, then a combination of interviewing and observing is ideal.

There are a variety of terms we use for observational data collection, from ethnography to fieldwork to participant observation. Many researchers use these terms fairly interchangeably, but here I will separately define them. The subject of this chapter is observation in general, or participant observation, to highlight the fact that observers can also be participants. The subject of chapter 14 will be deep ethnography, a particularly immersive form of study that is attractive for a certain subset of qualitative researchers. Both participant observation and deep ethnography are forms of fieldwork in which the researcher leaves their office and goes into a natural setting to record observations that take place in that setting.[1]

Participant observation (PO) is a field approach to gathering data in which the researcher enters a specific site for purposes of engagement or observation. Participation and observation can be conceptualized as a continuum, and any given study can fall somewhere on that line between full participation (researcher is a member of the community or organization being studied) and observation (researcher pretends to be a fly on the wall surreptitiously but mostly by permission, recording what happens). Participant observation forms the heart of ethnographic research, an approach, if you remember, that seeks to understand and write about a particular culture or subculture. We’ll discuss what I am calling deep ethnography in the next chapter, where researchers often embed themselves for months if not years or even decades with a particular group to be able to fully capture “what it’s like.” But there are lighter versions of PO that can form the basis of a research study or that can supplement or work with other forms of data collection, such as interviews or archival research. This chapter will focus on these lighter versions, although note that much of what is said here can also apply to deep ethnography (chapter 14).

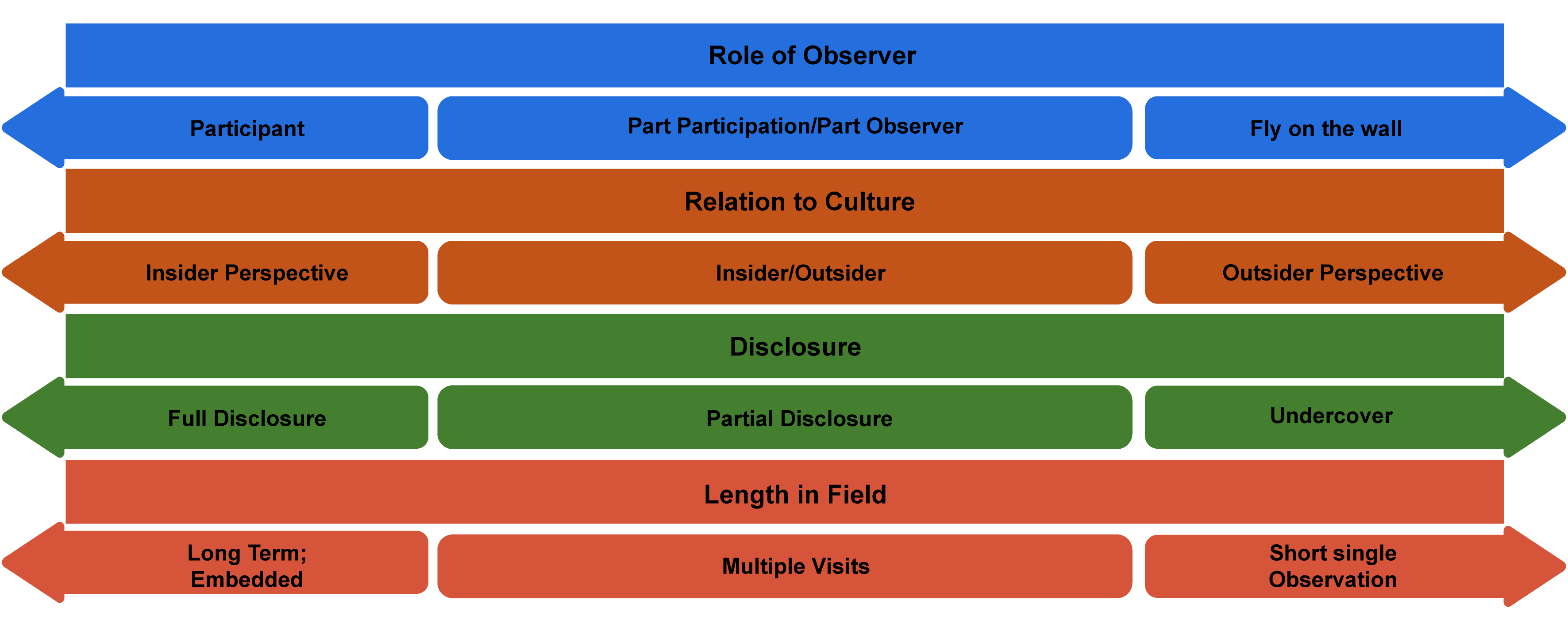

PO methods of gathering data present some special considerations—How involved is the researcher? How close is she to the subjects or site being studied? And how might her own social location—identity, position—affect the study? These are actually great questions for any kind of qualitative data collection but particularly apt when the researcher “enters the field,” so to speak. It is helpful to visualize where one falls on a continuum or series of continua (figure 13.1).

Let’s take a few examples and see how these continua work. Think about each of the following scenarios, and map them onto the possibilities of figure 13.1:

- a nursing student during COVID doing research on patient/doctor interactions in the ICU

- a graduate student accompanying a police officer during her rounds one day in a part of the city the graduate student has never visited

- a professor raised Amish who goes back to her hometown to conduct research on Amish marriage practices for one month

- a sociologist who visits the Oregon Country Fair (OCF) every year and decides to write down his observations one year

- (What if the sociologist was also a member of the OCF board and camping crew?)

Depending on how the researcher answers those questions and where they stand on the P.O. continuum, various techniques will be more or less effective. For example, in cases where the researcher is a participant, writing reflective fieldnotes at the end of the day may be the primary form of data collected. After all, if the researcher is fully participating, they probably don’t have the time or ability to pull out a notepad and ask people questions. On the other side, when a researcher is more of an observer, this is exactly what they might do, so long as the people they are interrogating are able to answer while they are going about their business. The more an observer, the more likely the researcher will engage in relatively structured interviews (using techniques discussed in chapters 11 and 12); the more a participant, the more likely casual conversations or “unstructured interviews” will form the core of the data collected.[2]

Observation and Qualitative Traditions

Observational techniques are used whenever the researcher wants to document actual behaviors and practices as they happen (not as they are explained or recorded historically). Many traditions of inquiry employ observational data collection, but not all traditions employ them in the same way. Chapter 14 will cover one very specific tradition: ethnography. Because the word ethnography is sometimes used for all fieldwork, I am calling the subject of chapter 14 deep ethnography, those studies that take as their focus the documentation through the description of a culture or subculture. Deeply immersive, this tradition of ethnography typically entails several months or even years in the field. But there are plenty of other uses of observation that are less burdensome to the researcher.

Grounded Theory, in which theories emerge from a rigorous and systematic process of induction, is amenable to both interviewing and observing forms of data collection, and some of the best Grounded Theory works employ a deft combination of both. Often closely aligned with Grounded Theory in sociology is the tradition of symbolic interactionism (SI). Interviews and observations in combination are necessary to properly address the SI question, What common understandings give meaning to people’s interactions? Gary Alan Fine’s body of work fruitfully combines interviews and observations to build theory in response to this SI question. His Authors of the Storm: Meteorologists and the Culture of Prediction is based on field observation and interviews at the Storm Prediction Center in Oklahoma; the National Weather Service in Washington, DC; and a few regional weather forecasting outlets in the Midwest. Using what he heard and what he observed, he builds a theory of weather forecasting based on social and cultural factors that take place inside local offices. In Morel Tales: The Culture of Mushrooming, Fine investigates the world of mushroom hunters through participant observation and interviews, eventually building a theory of “naturework” to describe how the meanings people hold about the world are constructed and are socially organized—our understanding of “nature” is based on human nature, if you will.

Phenomenology typically foregrounds interviewing, as the purpose of this tradition is to gather people’s understandings and meanings about a phenomenon. However, it is quite common for phenomenological interviewing to be supplemented with some observational data, especially as a check on the “reality” of the situations being described by those interviewed. In my own work, for example, I supplemented primary interviews with working-class college students with some participant observational work on the campus in which they were studying. This helped me gather information on the general silence about class on campus, which made the salience of class in the interviews even more striking (Hurst 2010a).

Critical theories such as standpoint approaches, feminist theory, and Critical Race Theory are often multimethod in design. Interviews, observations (possibly participation), and archival/historical data are all employed to gather an understanding of how a group of persons experiences a particular setting or institution or phenomenon and how things can be made more just. In Making Elite Lawyers, Robert Granfield (1992) drew on both classroom observations and in-depth interviews with students to document the conservatizing effects of the Harvard legal education on working-class students, female students, and students of color. In this case, stories recounted by students were amplified by searing examples of discrimination and bias observed by Granfield and reported in full detail through his fieldnotes.

Entry Access and Issues

Managing your entry into a field site is one of the most important and nerve-wracking aspects of doing ethnographic research. Unlike interviews, which can be conducted in neutral settings, the field is an actual place with its own rules and customs that you are seeking to explore. How you “gain access” will depend on what kind of field you are entering. If your field site is a physical location with walls and a front desk (such as an office building or an elementary school), you will need permission from someone in the organization to enter and to conduct your study. Negotiating this might take weeks or even months. If your field site is a public site (such as a public dog park or city sidewalks), there is no “official” gatekeeper, but you will still probably need to find a person present at the site who can vouch for you (e.g., other dog owners or people hanging out on their stoops).[3] And if your field site is semipublic, as in a shopping mall, you might have to weigh the pros and cons of gaining “official” permission, as this might impede your progress or be difficult to ascertain whose permission to request. If you recall, many of the ethical dilemmas discussed in chapter 7 were about just such issues.

Even with official (or unofficial) permission to enter the site, however, your quest to gain access is not done. You will still need to gain the trust and permission of the people you encounter at that site. If you are a mere observer in a public setting, you probably do not need each person you observe to sign a consent form, but if you are a participant in an event or enterprise who is also taking notes and asking people questions, you probably do. Each study is unique here, so I recommend talking through the ethics of permission and consent seeking with a faculty mentor.

A separate but related issue from permission is how you will introduce yourself and your presence. How you introduce yourself to people in the field will depend very much on what level of participation you have chosen as well as whether you are an insider or outsider. Sometimes your presence will go unremarked, whereas other times you may stick out like a very sore thumb. Lareau (2021) advises that you be “vague but accurate” when explaining your presence. You don’t want to use academic jargon (unless your field is the academy!) that would be off-putting to the people you meet. Nor do you want to deceive anyone. “Hi, I’m Allison, and I am here to observe how students use career services” is accurate and simple and more effective than “I am here to study how race, class, and gender affect college students’ interactions with career services personnel.”

Researcher Note

Something that surprised me and that I still think about a lot is how to explain to respondents what I’m doing and why and how to help them feel comfortable with field work. When I was planning fieldwork for my dissertation, I was thinking of it from a researcher’s perspective and not from a respondent’s perspective. It wasn’t until I got into the field that I started to realize what a strange thing I was planning to spend my time on and asking others to allow me to do. Like, can I follow you around and write notes? This varied a bit by site—it was easier to ask to sit in on meetings, for example—but asking people to let me spend a lot of time with them was awkward for me and for them. I ended up asking if I could shadow them, a verb that seemed to make clear what I hoped to be able to do. But even this didn’t get around issues like respondents’ self-consciousness or my own. For example, respondents sometimes told me that their lives were “boring” and that they felt embarrassed to have someone else shadow them when they weren’t “doing anything.” Similarly, I would feel uncomfortable in social settings where I knew only one person. Taking field notes is not something to do at a party, and when introduced as a researcher, people would sometimes ask, “So are you researching me right now?” The answer to that is always yes. I figured out ways of taking notes that worked (I often sent myself text messages with jotted notes) and how to get more comfortable explaining what I wanted to be able to do (wanting to see the campus from the respondent’s perspective, for example), but it is still something I work to improve.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life and coauthor of Geographies of Campus Inequality

Reflexivity in Fieldwork

As always, being aware of who you are, how you are likely to be read by others in the field, and how your own experiences and understandings of the world are likely to affect your reading of others in the field are all very important to conducting successful research. When Annette Lareau (2021) was managing a team of graduate student researchers in her study of parents and children, she noticed that her middle-class graduate students took in stride the fact that children called adults by their first names, while her working-class-origin graduate students “were shocked by what they considered the rudeness and disrespect middle-class children showed toward their parents and other adults” (151). This “finding” emerged from particular fieldnotes taken by particular research assistants. Having graduate students with different class backgrounds turned out to be useful. Being reflexive in this case meant interrogating one’s own expectations about how children should act toward adults. Creating thick descriptions in the fieldnotes (e.g., describing how children name adults) is important, but thinking about one’s response to those descriptions is equally so. Without reflection, it is possible that important aspects never even make it into the fieldnotes because they seem “unremarkable.”

The Data of Observational Work: Fieldnotes

In interview data collection, recordings of interviews are transcribed into the data of the study. This is not possible for much PO work because (1) aural recordings of observations aren’t possible and (2) conversations that take place on-site are not easily recorded. Instead, the participant observer takes notes, either during the fieldwork or at the day’s end. These notes, called “fieldnotes,” are then the primary form of data for PO work.

Writing fieldnotes takes a lot of time. Because fieldnotes are your primary form of data, you cannot be stingy with the time it takes. Most practitioners suggest it takes at least the same amount of time to write up notes as it takes to be in the field, and many suggest it takes double the time. If you spend three hours at a meeting of the organization you are observing, it is a good idea to set aside five to six hours to write out your fieldnotes. Different researchers use different strategies about how and when to do this. Somewhat obviously, the earlier you can write down your notes, the more likely they are to be accurate. Writing them down at the end of the day is thus the default practice. However, if you are plainly exhausted, spending several hours trying to recall important details may be counterproductive. Writing fieldnotes the next morning, when you are refreshed and alert, may work better.

Reseaarcher Note

How do you take fieldnotes? Any advice for those wanting to conduct an ethnographic study?

Fieldnotes are so important, especially for qualitative researchers. A little advice when considering how you approach fieldnotes: Record as much as possible! Sometimes I write down fieldnotes, and I often audio-record them as well to transcribe later. Sometimes the space to speak what I observed is helpful and allows me to be able to go a little more in-depth or to talk out something that I might not quite have the words for just yet. Within my fieldnote, I include feelings and think about the following questions: How do I feel before data collection? How did I feel when I was engaging/watching? How do I feel after data collection? What was going on for me before this particular data collection? What did I notice about how folks were engaging? How were participants feeling, and how do I know this? Is there anything that seems different than other data collections? What might be going on in the world that might be impacting the participants? As a qualitative researcher, it’s also important to remember our own influences on the research—our feelings or current world news may impact how we observe or what we might capture in fieldnotes.

—Kim McAloney, PhD, College Student Services Administration Ecampus coordinator and instructor

What should be included in those fieldnotes? The obvious answer is “everything you observed and heard relevant to your research question.” The difficulty is that you often don’t know what is relevant to your research question when you begin, as your research question itself can develop and transform during the course of your observations. For example, let us say you begin a study of second-grade classrooms with the idea that you will observe gender dynamics between both teacher and students and students and students. But after five weeks of observation, you realize you are taking a lot of notes about how teachers validate certain attention-seeking behaviors among some students while ignoring those of others. For example, when Daisy (White female) interrupts a discussion on frogs to tell everyone she has a frog named Ribbit, the teacher smiles and asks her to tell the students what Ribbit is like. In contrast, when Solomon (Black male) interrupts a discussion on the planets to tell everyone his big brother is called Jupiter by their stepfather, the teacher frowns and shushes him. These notes spark interest in how teachers favor and develop some students over others and the role of gender, race, and class in these teacher practices. You then begin to be much more careful in recording these observations, and you are a little less attentive to the gender dynamics among students. But note that had you not been fairly thorough in the first place, these crucial insights about teacher favoritism might never have been made.

Here are some suggestions for things to include in your fieldnotes as you begin: (1) descriptions of the physical setting; (2) people in the site: who they are and how they interact with one another (what roles they are taking on); and (3) things overheard: conversations, exchanges, questions. While you should develop your own personal system for organizing these fieldnotes (computer vs. printed journal, for example), at a minimum, each set of fieldnotes should include the date, time in the field, persons observed, and location specifics. You might also add keywords to each set so that you can search by names of participants, dates, and locations. Lareau (2021:167) recommends covering the following key issues, which mnemonically spell out WRITE—W: who, what, when, where, how; R: reaction (responses to the action in question and the response to the response); I: inaction (silence or nonverbal response to an action); T: timing (how slowly or quickly someone is speaking); and E: emotions (nonverbal signs of emotion and/or stoicism).

In addition to the observational fieldnotes, if you have time, it is a good practice to write reflective memos in which you ask yourself what you have learned (either about the study or about your abilities in the field). If you don’t have time to do this for every set of fieldnotes, at least get in the practice of memoing at certain key junctures, perhaps after reading through a certain number of fieldnotes (e.g., every third day of fieldnotes, you set aside two hours to read through the notes and memo). These memos can then be appended to relevant fieldnotes. You will be grateful for them when it comes time to analyze your data, as they are a preliminary by-the-seat-of-your-pants analysis. They also help steer you toward the study you want to pursue rather than allow you to wallow in unfocused data.

Ethics of Fieldwork

Because most fieldwork requires multiple and intense interactions (even if merely observational) with real living people as they go about their business, there are potentially more ethical choices to be made. In addition to the ethics of gaining entry and permission discussed above, there are issues of accurate representation, of respecting privacy, of adequate financial compensation, and sometimes of financial and other forms of assistance (when observing/interacting with low-income persons or other marginalized populations). In other words, the ethical decision of fieldwork is never concluded by obtaining a signature on a consent form. Read this brief selection from Pascale’s (2021) methods description (observation plus interviews) to see how many ethical decisions she made:

Throughout I kept detailed ethnographic field and interview records, which included written notes, recorded notes, and photographs. I asked everyone who was willing to sit for a formal interview to speak only for themselves and offered each of them a prepaid Visa Card worth $25–40. I also offered everyone the opportunity to keep the card and erase the tape completely at any time they were dissatisfied with the interview in any way. No one asked for the tape to be erased; rather, people remarked on the interview being a really good experience because they felt heard. Each interview was professionally transcribed and for the most part the excerpts in this book are literal transcriptions. In a few places, the excerpta have been edited to reduce colloquial features of speech (e.g., you know, like, um) and some recursive elements common to spoken language. A few excerpts were placed into standard English for clarity. I made this choice for the benefit of readers who might otherwise find the insights and ideas harder to parse in the original. However, I have to acknowledge this as an act of class-based violence. I tried to keep the original phrasing whenever possible. (235)

Summary Checklist for Successful Participant Observation

The following are ten suggestions for being successful in the field, slightly paraphrased from Patton (2002:331). Here, I take those ten suggestions and turn them into an extended “checklist” to use when designing and conducting fieldwork.

- Consider all possible approaches to your field and your position relative to that field (see figure 13.2). Choose wisely and purposely. If you have access to a particular site or are part of a particular culture, consider the advantages (and disadvantages) of pursuing research in that area. Clarify the amount of disclosure you are willing to share with those you are observing, and justify that decision.

- Take thorough and descriptive field notes. Consider how you will record them. Where your research is located will affect what kinds of field notes you can take and when, but do not fail to write them! Commit to a regular recording time. Your field notes will probably be the primary data source you collect, so your study’s success will depend on thick descriptions and analytical memos you write to yourself about what you are observing.

- Permit yourself to be flexible. Consider alternative lines of inquiry as you proceed. You might enter the field expecting to find something only to have your attention grabbed by something else entirely. This is perfectly fine (and, in some traditions, absolutely crucial for excellent results). When you do see your attention shift to an emerging new focus, take a step back, look at your original research design, and make careful decisions about what might need revising to adapt to these new circumstances.

- Include triangulated data as a means of checking your observations. If you are that ICU nurse watching patient/doctor interactions, you might want to add a few interviews with patients to verify your interpretation of the interaction. Or perhaps pull some public data on the number of arrests for jaywalking if you are the student accompanying police on their rounds to find out if the large number of arrests you witnessed was typical.

- Respect the people you are witnessing and recording, and allow them to speak for themselves whenever possible. Using direct quotes (recorded in your field notes or as supplementary recorded interviews) is another way to check the validity of the analyses of your observations. When designing your research, think about how you can ensure the voices of those you are interested in get included.

- Choose your informants wisely. Who are they relative to the field you are exploring? What are the limitations (ethical and strategic) in using those particular informants, guides, and gatekeepers? Limit your reliance on them to the extent possible.

- Consider all the stages of fieldwork, and have appropriate plans for each. Recognize that different talents are required at different stages of the data-collection process. In the beginning, you will probably spend a great deal of time building trust and rapport and will have less time to focus on what is actually occurring. That’s normal. Later, however, you will want to be more focused on and disciplined in collecting data while also still attending to maintaining relationships necessary for your study’s success. Sometimes, especially when you have been invited to the site, those granting access to you will ask for feedback. Be strategic about when giving that feedback is appropriate. Consider how to extricate yourself from the site and the participants when your study is coming to an end. Have an ethical exit plan.

- Allow yourself to be immersed in the scene you are observing. This is true even if you are observing a site as an outsider just one time. Make an effort to see things through the eyes of the participants while at the same time maintaining an analytical stance. This is a tricky balance to do, of course, and is more of an art than a science. Practice it. Read about how others have achieved it.

- Create a practice of separating your descriptive notes from your analytical observations. This may be as clear as dividing a sheet of paper into two columns, one for description only and the other for questions or interpretation (as we saw in chapter 11 on interviewing), or it may mean separating out the time you dedicate to descriptions from the time you reread and think deeply about those detailed descriptions. However you decide to do it, recognize that these are two separate activities, both of which are essential to your study’s success.

- As always with qualitative research, be reflective and reflexive. Do not forget how your own experience and social location may affect both your interpretation of what you observe and the very things you observe themselves (e.g., where a patient says more forgiving things about an observably rude doctor because they read you, a nursing student, as likely to report any negative comments back to the doctor). Keep a research journal!

Further Readings

Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. 2nd ed. University of Chicago Press. Excellent guide that uses actual unfinished fieldnote to illustrate various options for composing, reviewing, and incorporating fieldnote into publications.

Lareau, Annette. 2021. Listening to People: A Practical Guide to Interviewing, Participant Observation, Data Analysis, and Writing It All Up. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Includes actual fieldnote from various studies with a really helpful accompanying discussion about how to improve them!

Wolfinger, Nicholas H. 2002. “On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2(1):85–95. Uses fieldnote from various sources to show how the researcher’s expectations and preexisting knowledge affect what gets written about; offers strategies for taking useful fieldnote.

- Note that leaving one’s office to interview someone in a coffee shop would not be considered fieldwork because the coffee shop is not an element of the study. If one sat down in a coffee shop and recorded observations, then this would be fieldwork. ↵

- This is one reason why I have chosen to discuss deep ethnography in a separate chapter (chapter 14). ↵

- This person is sometimes referred to as the informant (and more on these characters in chapter 14). ↵

Chapter 1. Introduction

“Science is in danger, and for that reason it is becoming dangerous” -Pierre Bourdieu, Science of Science and Reflexivity

Why an Open Access Textbook on Qualitative Research Methods?

I have been teaching qualitative research methods to both undergraduates and graduate students for many years. Although there are some excellent textbooks out there, they are often costly, and none of them, to my mind, properly introduces qualitative research methods to the beginning student (whether undergraduate or graduate student). In contrast, this open-access textbook is designed as a (free) true introduction to the subject, with helpful, practical pointers on how to conduct research and how to access more advanced instruction.

Textbooks are typically arranged in one of two ways: (1) by technique (each chapter covers one method used in qualitative research); or (2) by process (chapters advance from research design through publication). But both of these approaches are necessary for the beginner student. This textbook will have sections dedicated to the process as well as the techniques of qualitative research. This is a true “comprehensive” book for the beginning student. In addition to covering techniques of data collection and data analysis, it provides a road map of how to get started and how to keep going and where to go for advanced instruction. It covers aspects of research design and research communication as well as methods employed. Along the way, it includes examples from many different disciplines in the social sciences.

The primary goal has been to create a useful, accessible, engaging textbook for use across many disciplines. And, let’s face it. Textbooks can be boring. I hope readers find this to be a little different. I have tried to write in a practical and forthright manner, with many lively examples and references to good and intellectually creative qualitative research. Woven throughout the text are short textual asides (in colored textboxes) by professional (academic) qualitative researchers in various disciplines. These short accounts by practitioners should help inspire students. So, let’s begin!

What is Research?

When we use the word research, what exactly do we mean by that? This is one of those words that everyone thinks they understand, but it is worth beginning this textbook with a short explanation. We use the term to refer to “empirical research,” which is actually a historically specific approach to understanding the world around us. Think about how you know things about the world.[1] You might know your mother loves you because she’s told you she does. Or because that is what “mothers” do by tradition. Or you might know because you’ve looked for evidence that she does, like taking care of you when you are sick or reading to you in bed or working two jobs so you can have the things you need to do OK in life. Maybe it seems churlish to look for evidence; you just take it “on faith” that you are loved.

Only one of the above comes close to what we mean by research. Empirical research is research (investigation) based on evidence. Conclusions can then be drawn from observable data. This observable data can also be “tested” or checked. If the data cannot be tested, that is a good indication that we are not doing research. Note that we can never “prove” conclusively, through observable data, that our mothers love us. We might have some “disconfirming evidence” (that time she didn’t show up to your graduation, for example) that could push you to question an original hypothesis, but no amount of “confirming evidence” will ever allow us to say with 100% certainty, “my mother loves me.” Faith and tradition and authority work differently. Our knowledge can be 100% certain using each of those alternative methods of knowledge, but our certainty in those cases will not be based on facts or evidence.

For many periods of history, those in power have been nervous about “science” because it uses evidence and facts as the primary source of understanding the world, and facts can be at odds with what power or authority or tradition want you to believe. That is why I say that scientific empirical research is a historically specific approach to understand the world. You are in college or university now partly to learn how to engage in this historically specific approach.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe, there was a newfound respect for empirical research, some of which was seriously challenging to the established church. Using observations and testing them, scientists found that the earth was not at the center of the universe, for example, but rather that it was but one planet of many which circled the sun.[2] For the next two centuries, the science of astronomy, physics, biology, and chemistry emerged and became disciplines taught in universities. All used the scientific method of observation and testing to advance knowledge. Knowledge about people, however, and social institutions, however, was still left to faith, tradition, and authority. Historians and philosophers and poets wrote about the human condition, but none of them used research to do so.[3]

It was not until the nineteenth century that “social science” really emerged, using the scientific method (empirical observation) to understand people and social institutions. New fields of sociology, economics, political science, and anthropology emerged. The first sociologists, people like Auguste Comte and Karl Marx, sought specifically to apply the scientific method of research to understand society, Engels famously claiming that Marx had done for the social world what Darwin did for the natural world, tracings its laws of development. Today we tend to take for granted the naturalness of science here, but it is actually a pretty recent and radical development.

To return to the question, “does your mother love you?” Well, this is actually not really how a researcher would frame the question, as it is too specific to your case. It doesn’t tell us much about the world at large, even if it does tell us something about you and your relationship with your mother. A social science researcher might ask, “do mothers love their children?” Or maybe they would be more interested in how this loving relationship might change over time (e.g., “do mothers love their children more now than they did in the 18th century when so many children died before reaching adulthood?”) or perhaps they might be interested in measuring quality of love across cultures or time periods, or even establishing “what love looks like” using the mother/child relationship as a site of exploration. All of these make good research questions because we can use observable data to answer them.

What is Qualitative Research?

“All we know is how to learn. How to study, how to listen, how to talk, how to tell. If we don’t tell the world, we don’t know the world. We’re lost in it, we die.” -Ursula LeGuin, The Telling

At its simplest, qualitative research is research about the social world that does not use numbers in its analyses. All those who fear statistics can breathe a sigh of relief – there are no mathematical formulae or regression models in this book! But this definition is less about what qualitative research can be and more about what it is not. To be honest, any simple statement will fail to capture the power and depth of qualitative research. One way of contrasting qualitative research to quantitative research is to note that the focus of qualitative research is less about explaining and predicting relationships between variables and more about understanding the social world. To use our mother love example, the question about “what love looks like” is a good question for the qualitative researcher while all questions measuring love or comparing incidences of love (both of which require measurement) are good questions for quantitative researchers. Patton writes,

Qualitative data describe. They take us, as readers, into the time and place of the observation so that we know what it was like to have been there. They capture and communicate someone else’s experience of the world in his or her own words. Qualitative data tell a story. (Patton 2002:47)

Qualitative researchers are asking different questions about the world than their quantitative colleagues. Even when researchers are employed in “mixed methods” research (both quantitative and qualitative), they are using different methods to address different questions of the study. I do a lot of research about first-generation and working-college college students. Where a quantitative researcher might ask, how many first-generation college students graduate from college within four years? Or does first-generation college status predict high student debt loads? A qualitative researcher might ask, how does the college experience differ for first-generation college students? What is it like to carry a lot of debt, and how does this impact the ability to complete college on time? Both sets of questions are important, but they can only be answered using specific tools tailored to those questions. For the former, you need large numbers to make adequate comparisons. For the latter, you need to talk to people, find out what they are thinking and feeling, and try to inhabit their shoes for a little while so you can make sense of their experiences and beliefs.

Examples of Qualitative Research

You have probably seen examples of qualitative research before, but you might not have paid particular attention to how they were produced or realized that the accounts you were reading were the result of hours, months, even years of research “in the field.” A good qualitative researcher will present the product of their hours of work in such a way that it seems natural, even obvious, to the reader. Because we are trying to convey what it is like answers, qualitative research is often presented as stories – stories about how people live their lives, go to work, raise their children, interact with one another. In some ways, this can seem like reading particularly insightful novels. But, unlike novels, there are very specific rules and guidelines that qualitative researchers follow to ensure that the “story” they are telling is accurate, a truthful rendition of what life is like for the people being studied. Most of this textbook will be spent conveying those rules and guidelines. Let’s take a look, first, however, at three examples of what the end product looks like. I have chosen these three examples to showcase very different approaches to qualitative research, and I will return to these five examples throughout the book. They were all published as whole books (not chapters or articles), and they are worth the long read, if you have the time. I will also provide some information on how these books came to be and the length of time it takes to get them into book version. It is important you know about this process, and the rest of this textbook will help explain why it takes so long to conduct good qualitative research!

Example 1: The End Game (ethnography + interviews)

Corey Abramson is a sociologist who teaches at the University of Arizona. In 2015 he published The End Game: How Inequality Shapes our Final Years (2015). This book was based on the research he did for his dissertation at the University of California-Berkeley in 2012. Actually, the dissertation was completed in 2012 but the work that was produced that took several years. The dissertation was entitled, “This is How We Live, This is How We Die: Social Stratification, Aging, and Health in Urban America” (2012). You can see how the book version, which was written for a more general audience, has a more engaging sound to it, but that the dissertation version, which is what academic faculty read and evaluate, has a more descriptive title. You can read the title and know that this is a study about aging and health and that the focus is going to be inequality and that the context (place) is going to be “urban America.” It’s a study about “how” people do something – in this case, how they deal with aging and death. This is the very first sentence of the dissertation, “From our first breath in the hospital to the day we die, we live in a society characterized by unequal opportunities for maintaining health and taking care of ourselves when ill. These disparities reflect persistent racial, socio-economic, and gender-based inequalities and contribute to their persistence over time” (1). What follows is a truthful account of how that is so.

Cory Abramson spent three years conducting his research in four different urban neighborhoods. We call the type of research he conducted “comparative ethnographic” because he designed his study to compare groups of seniors as they went about their everyday business. It’s comparative because he is comparing different groups (based on race, class, gender) and ethnographic because he is studying the culture/way of life of a group.[4] He had an educated guess, rooted in what previous research had shown and what social theory would suggest, that people’s experiences of aging differ by race, class, and gender. So, he set up a research design that would allow him to observe differences. He chose two primarily middle-class (one was racially diverse and the other was predominantly White) and two primarily poor neighborhoods (one was racially diverse and the other was predominantly African American). He hung out in senior centers and other places seniors congregated, watched them as they took the bus to get prescriptions filled, sat in doctor’s offices with them, and listened to their conversations with each other. He also conducted more formal conversations, what we call in-depth interviews, with sixty seniors from each of the four neighborhoods. As with a lot of fieldwork, as he got closer to the people involved, he both expanded and deepened his reach –

By the end of the project, I expanded my pool of general observations to include various settings frequented by seniors: apartment building common rooms, doctors’ offices, emergency rooms, pharmacies, senior centers, bars, parks, corner stores, shopping centers, pool halls, hair salons, coffee shops, and discount stores. Over the course of the three years of fieldwork, I observed hundreds of elders, and developed close relationships with a number of them. (2012:10)

When Abramson rewrote the dissertation for a general audience and published his book in 2015, it got a lot of attention. It is a beautifully written book and it provided insight into a common human experience that we surprisingly know very little about. It won the Outstanding Publication Award by the American Sociological Association Section on Aging and the Life Course and was featured in the New York Times. The book was about aging, and specifically how inequality shapes the aging process, but it was also about much more than that. It helped show how inequality affects people’s everyday lives. For example, by observing the difficulties the poor had in setting up appointments and getting to them using public transportation and then being made to wait to see a doctor, sometimes in standing-room-only situations, when they are unwell, and then being treated dismissively by hospital staff, Abramson allowed readers to feel the material reality of being poor in the US. Comparing these examples with seniors with adequate supplemental insurance who have the resources to hire car services or have others assist them in arranging care when they need it, jolts the reader to understand and appreciate the difference money makes in the lives and circumstances of us all, and in a way that is different than simply reading a statistic (“80% of the poor do not keep regular doctor’s appointments”) does. Qualitative research can reach into spaces and places that often go unexamined and then reports back to the rest of us what it is like in those spaces and places.

Example 2: Racing for Innocence (Interviews + Content Analysis + Fictional Stories)

Jennifer Pierce is a Professor of American Studies at the University of Minnesota. Trained as a sociologist, she has written a number of books about gender, race, and power. Her very first book, Gender Trials: Emotional Lives in Contemporary Law Firms, published in 1995, is a brilliant look at gender dynamics within two law firms. Pierce was a participant observer, working as a paralegal, and she observed how female lawyers and female paralegals struggled to obtain parity with their male colleagues.

Fifteen years later, she reexamined the context of the law firm to include an examination of racial dynamics, particularly how elite white men working in these spaces created and maintained a culture that made it difficult for both female attorneys and attorneys of color to thrive. Her book, Racing for Innocence: Whiteness, Gender, and the Backlash Against Affirmative Action, published in 2012, is an interesting and creative blending of interviews with attorneys, content analyses of popular films during this period, and fictional accounts of racial discrimination and sexual harassment. The law firm she chose to study had come under an affirmative action order and was in the process of implementing equitable policies and programs. She wanted to understand how recipients of white privilege (the elite white male attorneys) come to deny the role they play in reproducing inequality. Through interviews with attorneys who were present both before and during the affirmative action order, she creates a historical record of the “bad behavior” that necessitated new policies and procedures, but also, and more importantly, probed the participants’ understanding of this behavior. It should come as no surprise that most (but not all) of the white male attorneys saw little need for change, and that almost everyone else had accounts that were different if not sometimes downright harrowing.

I’ve used Pierce’s book in my qualitative research methods courses as an example of an interesting blend of techniques and presentation styles. My students often have a very difficult time with the fictional accounts she includes. But they serve an important communicative purpose here. They are her attempts at presenting “both sides” to an objective reality – something happens (Pierce writes this something so it is very clear what it is), and the two participants to the thing that happened have very different understandings of what this means. By including these stories, Pierce presents one of her key findings – people remember things differently and these different memories tend to support their own ideological positions. I wonder what Pierce would have written had she studied the murder of George Floyd or the storming of the US Capitol on January 6 or any number of other historic events whose observers and participants record very different happenings.

This is not to say that qualitative researchers write fictional accounts. In fact, the use of fiction in our work remains controversial. When used, it must be clearly identified as a presentation device, as Pierce did. I include Racing for Innocence here as an example of the multiple uses of methods and techniques and the way that these work together to produce better understandings by us, the readers, of what Pierce studied. We readers come away with a better grasp of how and why advantaged people understate their own involvement in situations and structures that advantage them. This is normal human behavior, in other words. This case may have been about elite white men in law firms, but the general insights here can be transposed to other settings. Indeed, Pierce argues that more research needs to be done about the role elites play in the reproduction of inequality in the workplace in general.

Example 3: Amplified Advantage (Mixed Methods: Survey Interviews + Focus Groups + Archives)

The final example comes from my own work with college students, particularly the ways in which class background affects the experience of college and outcomes for graduates. I include it here as an example of mixed methods, and for the use of supplementary archival research. I’ve done a lot of research over the years on first-generation, low-income, and working-class college students. I am curious (and skeptical) about the possibility of social mobility today, particularly with the rising cost of college and growing inequality in general. As one of the few people in my family to go to college, I didn’t grow up with a lot of examples of what college was like or how to make the most of it. And when I entered graduate school, I realized with dismay that there were very few people like me there. I worried about becoming too different from my family and friends back home. And I wasn’t at all sure that I would ever be able to pay back the huge load of debt I was taking on. And so I wrote my dissertation and first two books about working-class college students. These books focused on experiences in college and the difficulties of navigating between family and school (Hurst 2010a, 2012). But even after all that research, I kept coming back to wondering if working-class students who made it through college had an equal chance at finding good jobs and happy lives,

What happens to students after college? Do working-class students fare as well as their peers? I knew from my own experience that barriers continued through graduate school and beyond, and that my debtload was higher than that of my peers, constraining some of the choices I made when I graduated. To answer these questions, I designed a study of students attending small liberal arts colleges, the type of college that tried to equalize the experience of students by requiring all students to live on campus and offering small classes with lots of interaction with faculty. These private colleges tend to have more money and resources so they can provide financial aid to low-income students. They also attract some very wealthy students. Because they enroll students across the class spectrum, I would be able to draw comparisons. I ended up spending about four years collecting data, both a survey of more than 2000 students (which formed the basis for quantitative analyses) and qualitative data collection (interviews, focus groups, archival research, and participant observation). This is what we call a “mixed methods” approach because we use both quantitative and qualitative data. The survey gave me a large enough number of students that I could make comparisons of the how many kind, and to be able to say with some authority that there were in fact significant differences in experience and outcome by class (e.g., wealthier students earned more money and had little debt; working-class students often found jobs that were not in their chosen careers and were very affected by debt, upper-middle-class students were more likely to go to graduate school). But the survey analyses could not explain why these differences existed. For that, I needed to talk to people and ask them about their motivations and aspirations. I needed to understand their perceptions of the world, and it is very hard to do this through a survey.

By interviewing students and recent graduates, I was able to discern particular patterns and pathways through college and beyond. Specifically, I identified three versions of gameplay. Upper-middle-class students, whose parents were themselves professionals (academics, lawyers, managers of non-profits), saw college as the first stage of their education and took classes and declared majors that would prepare them for graduate school. They also spent a lot of time building their resumes, taking advantage of opportunities to help professors with their research, or study abroad. This helped them gain admission to highly-ranked graduate schools and interesting jobs in the public sector. In contrast, upper-class students, whose parents were wealthy and more likely to be engaged in business (as CEOs or other high-level directors), prioritized building social capital. They did this by joining fraternities and sororities and playing club sports. This helped them when they graduated as they called on friends and parents of friends to find them well-paying jobs. Finally, low-income, first-generation, and working-class students were often adrift. They took the classes that were recommended to them but without the knowledge of how to connect them to life beyond college. They spent time working and studying rather than partying or building their resumes. All three sets of students thought they were “doing college” the right way, the way that one was supposed to do college. But these three versions of gameplay led to distinct outcomes that advantaged some students over others. I titled my work “Amplified Advantage” to highlight this process.

These three examples, Cory Abramson’s The End Game, Jennifer Peirce’s Racing for Innocence, and my own Amplified Advantage, demonstrate the range of approaches and tools available to the qualitative researcher. They also help explain why qualitative research is so important. Numbers can tell us some things about the world, but they cannot get at the hearts and minds, motivations and beliefs of the people who make up the social worlds we inhabit. For that, we need tools that allow us to listen and make sense of what people tell us and show us. That is what good qualitative research offers us.

How Is This Book Organized?

This textbook is organized as a comprehensive introduction to the use of qualitative research methods. The first half covers general topics (e.g., approaches to qualitative research, ethics) and research design (necessary steps for building a successful qualitative research study). The second half reviews various data collection and data analysis techniques. Of course, building a successful qualitative research study requires some knowledge of data collection and data analysis so the chapters in the first half and the chapters in the second half should be read in conversation with each other. That said, each chapter can be read on its own for assistance with a particular narrow topic. In addition to the chapters, a helpful glossary can be found in the back of the book. Rummage around in the text as needed.

Chapter Descriptions

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the Research Design Process. How does one begin a study? What is an appropriate research question? How is the study to be done – with what methods? Involving what people and sites? Although qualitative research studies can and often do change and develop over the course of data collection, it is important to have a good idea of what the aims and goals of your study are at the outset and a good plan of how to achieve those aims and goals. Chapter 2 provides a road map of the process.

Chapter 3 describes and explains various ways of knowing the (social) world. What is it possible for us to know about how other people think or why they behave the way they do? What does it mean to say something is a “fact” or that it is “well-known” and understood? Qualitative researchers are particularly interested in these questions because of the types of research questions we are interested in answering (the how questions rather than the how many questions of quantitative research). Qualitative researchers have adopted various epistemological approaches. Chapter 3 will explore these approaches, highlighting interpretivist approaches that acknowledge the subjective aspect of reality – in other words, reality and knowledge are not objective but rather influenced by (interpreted through) people.

Chapter 4 focuses on the practical matter of developing a research question and finding the right approach to data collection. In any given study (think of Cory Abramson’s study of aging, for example), there may be years of collected data, thousands of observations, hundreds of pages of notes to read and review and make sense of. If all you had was a general interest area (“aging”), it would be very difficult, nearly impossible, to make sense of all of that data. The research question provides a helpful lens to refine and clarify (and simplify) everything you find and collect. For that reason, it is important to pull out that lens (articulate the research question) before you get started. In the case of the aging study, Cory Abramson was interested in how inequalities affected understandings and responses to aging. It is for this reason he designed a study that would allow him to compare different groups of seniors (some middle-class, some poor). Inevitably, he saw much more in the three years in the field than what made it into his book (or dissertation), but he was able to narrow down the complexity of the social world to provide us with this rich account linked to the original research question. Developing a good research question is thus crucial to effective design and a successful outcome. Chapter 4 will provide pointers on how to do this. Chapter 4 also provides an overview of general approaches taken to doing qualitative research and various “traditions of inquiry.”

Chapter 5 explores sampling. After you have developed a research question and have a general idea of how you will collect data (Observations? Interviews?), how do you go about actually finding people and sites to study? Although there is no “correct number” of people to interview, the sample should follow the research question and research design. Unlike quantitative research, qualitative research involves nonprobability sampling. Chapter 5 explains why this is so and what qualities instead make a good sample for qualitative research.

Chapter 6 addresses the importance of reflexivity in qualitative research. Related to epistemological issues of how we know anything about the social world, qualitative researchers understand that we the researchers can never be truly neutral or outside the study we are conducting. As observers, we see things that make sense to us and may entirely miss what is either too obvious to note or too different to comprehend. As interviewers, as much as we would like to ask questions neutrally and remain in the background, interviews are a form of conversation, and the persons we interview are responding to us. Therefore, it is important to reflect upon our social positions and the knowledges and expectations we bring to our work and to work through any blind spots that we may have. Chapter 6 provides some examples of reflexivity in practice and exercises for thinking through one’s own biases.

Chapter 7 is a very important chapter and should not be overlooked. As a practical matter, it should also be read closely with chapters 6 and 8. Because qualitative researchers deal with people and the social world, it is imperative they develop and adhere to a strong ethical code for conducting research in a way that does not harm. There are legal requirements and guidelines for doing so (see chapter 8), but these requirements should not be considered synonymous with the ethical code required of us. Each researcher must constantly interrogate every aspect of their research, from research question to design to sample through analysis and presentation, to ensure that a minimum of harm (ideally, zero harm) is caused. Because each research project is unique, the standards of care for each study are unique. Part of being a professional researcher is carrying this code in one’s heart, being constantly attentive to what is required under particular circumstances. Chapter 7 provides various research scenarios and asks readers to weigh in on the suitability and appropriateness of the research. If done in a class setting, it will become obvious fairly quickly that there are often no absolutely correct answers, as different people find different aspects of the scenarios of greatest importance. Minimizing the harm in one area may require possible harm in another. Being attentive to all the ethical aspects of one’s research and making the best judgments one can, clearly and consciously, is an integral part of being a good researcher.

Chapter 8, best to be read in conjunction with chapter 7, explains the role and importance of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). Under federal guidelines, an IRB is an appropriately constituted group that has been formally designated to review and monitor research involving human subjects. Every institution that receives funding from the federal government has an IRB. IRBs have the authority to approve, require modifications to (to secure approval), or disapprove research. This group review serves an important role in the protection of the rights and welfare of human research subjects. Chapter 8 reviews the history of IRBs and the work they do but also argues that IRBs’ review of qualitative research is often both over-inclusive and under-inclusive. Some aspects of qualitative research are not well understood by IRBs, given that they were developed to prevent abuses in biomedical research. Thus, it is important not to rely on IRBs to identify all the potential ethical issues that emerge in our research (see chapter 7).

Chapter 9 provides help for getting started on formulating a research question based on gaps in the pre-existing literature. Research is conducted as part of a community, even if particular studies are done by single individuals (or small teams). What any of us finds and reports back becomes part of a much larger body of knowledge. Thus, it is important that we look at the larger body of knowledge before we actually start our bit to see how we can best contribute. When I first began interviewing working-class college students, there was only one other similar study I could find, and it hadn’t been published (it was a dissertation of students from poor backgrounds). But there had been a lot published by professors who had grown up working class and made it through college despite the odds. These accounts by “working-class academics” became an important inspiration for my study and helped me frame the questions I asked the students I interviewed. Chapter 9 will provide some pointers on how to search for relevant literature and how to use this to refine your research question.

Chapter 10 serves as a bridge between the two parts of the textbook, by introducing techniques of data collection. Qualitative research is often characterized by the form of data collection – for example, an ethnographic study is one that employs primarily observational data collection for the purpose of documenting and presenting a particular culture or ethnos. Techniques can be effectively combined, depending on the research question and the aims and goals of the study. Chapter 10 provides a general overview of all the various techniques and how they can be combined.

The second part of the textbook moves into the doing part of qualitative research once the research question has been articulated and the study designed. Chapters 11 through 17 cover various data collection techniques and approaches. Chapters 18 and 19 provide a very simple overview of basic data analysis. Chapter 20 covers communication of the data to various audiences, and in various formats.

Chapter 11 begins our overview of data collection techniques with a focus on interviewing, the true heart of qualitative research. This technique can serve as the primary and exclusive form of data collection, or it can be used to supplement other forms (observation, archival). An interview is distinct from a survey, where questions are asked in a specific order and often with a range of predetermined responses available. Interviews can be conversational and unstructured or, more conventionally, semistructured, where a general set of interview questions “guides” the conversation. Chapter 11 covers the basics of interviews: how to create interview guides, how many people to interview, where to conduct the interview, what to watch out for (how to prepare against things going wrong), and how to get the most out of your interviews.

Chapter 12 covers an important variant of interviewing, the focus group. Focus groups are semistructured interviews with a group of people moderated by a facilitator (the researcher or researcher’s assistant). Focus groups explicitly use group interaction to assist in the data collection. They are best used to collect data on a specific topic that is non-personal and shared among the group. For example, asking a group of college students about a common experience such as taking classes by remote delivery during the pandemic year of 2020. Chapter 12 covers the basics of focus groups: when to use them, how to create interview guides for them, and how to run them effectively.

Chapter 13 moves away from interviewing to the second major form of data collection unique to qualitative researchers – observation. Qualitative research that employs observation can best be understood as falling on a continuum of “fly on the wall” observation (e.g., observing how strangers interact in a doctor’s waiting room) to “participant” observation, where the researcher is also an active participant of the activity being observed. For example, an activist in the Black Lives Matter movement might want to study the movement, using her inside position to gain access to observe key meetings and interactions. Chapter 13 covers the basics of participant observation studies: advantages and disadvantages, gaining access, ethical concerns related to insider/outsider status and entanglement, and recording techniques.

Chapter 14 takes a closer look at “deep ethnography” – immersion in the field of a particularly long duration for the purpose of gaining a deeper understanding and appreciation of a particular culture or social world. Clifford Geertz called this “deep hanging out.” Whereas participant observation is often combined with semistructured interview techniques, deep ethnography’s commitment to “living the life” or experiencing the situation as it really is demands more conversational and natural interactions with people. These interactions and conversations may take place over months or even years. As can be expected, there are some costs to this technique, as well as some very large rewards when done competently. Chapter 14 provides some examples of deep ethnographies that will inspire some beginning researchers and intimidate others.

Chapter 15 moves in the opposite direction of deep ethnography, a technique that is the least positivist of all those discussed here, to mixed methods, a set of techniques that is arguably the most positivist. A mixed methods approach combines both qualitative data collection and quantitative data collection, commonly by combining a survey that is analyzed statistically (e.g., cross-tabs or regression analyses of large number probability samples) with semi-structured interviews. Although it is somewhat unconventional to discuss mixed methods in textbooks on qualitative research, I think it is important to recognize this often-employed approach here. There are several advantages and some disadvantages to taking this route. Chapter 16 will describe those advantages and disadvantages and provide some particular guidance on how to design a mixed methods study for maximum effectiveness.

Chapter 16 covers data collection that does not involve live human subjects at all – archival and historical research (chapter 17 will also cover data that does not involve interacting with human subjects). Sometimes people are unavailable to us, either because they do not wish to be interviewed or observed (as is the case with many “elites”) or because they are too far away, in both place and time. Fortunately, humans leave many traces and we can often answer questions we have by examining those traces. Special collections and archives can be goldmines for social science research. This chapter will explain how to access these places, for what purposes, and how to begin to make sense of what you find.

Chapter 17 covers another data collection area that does not involve face-to-face interaction with humans: content analysis. Although content analysis may be understood more properly as a data analysis technique, the term is often used for the entire approach, which will be the case here. Content analysis involves interpreting meaning from a body of text. This body of text might be something found in historical records (see chapter 16) or something collected by the researcher, as in the case of comment posts on a popular blog post. I once used the stories told by student loan debtors on the website studentloanjustice.org as the content I analyzed. Content analysis is particularly useful when attempting to define and understand prevalent stories or communication about a topic of interest. In other words, when we are less interested in what particular people (our defined sample) are doing or believing and more interested in what general narratives exist about a particular topic or issue. This chapter will explore different approaches to content analysis and provide helpful tips on how to collect data, how to turn that data into codes for analysis, and how to go about presenting what is found through analysis.

Where chapter 17 has pushed us towards data analysis, chapters 18 and 19 are all about what to do with the data collected, whether that data be in the form of interview transcripts or fieldnotes from observations. Chapter 18 introduces the basics of coding, the iterative process of assigning meaning to the data in order to both simplify and identify patterns. What is a code and how does it work? What are the different ways of coding data, and when should you use them? What is a codebook, and why do you need one? What does the process of data analysis look like?

Chapter 19 goes further into detail on codes and how to use them, particularly the later stages of coding in which our codes are refined, simplified, combined, and organized. These later rounds of coding are essential to getting the most out of the data we’ve collected. As students are often overwhelmed with the amount of data (a corpus of interview transcripts typically runs into the hundreds of pages; fieldnotes can easily top that), this chapter will also address time management and provide suggestions for dealing with chaos and reminders that feeling overwhelmed at the analysis stage is part of the process. By the end of the chapter, you should understand how “findings” are actually found.

The book concludes with a chapter dedicated to the effective presentation of data results. Chapter 20 covers the many ways that researchers communicate their studies to various audiences (academic, personal, political), what elements must be included in these various publications, and the hallmarks of excellent qualitative research that various audiences will be expecting. Because qualitative researchers are motivated by understanding and conveying meaning, effective communication is not only an essential skill but a fundamental facet of the entire research project. Ethnographers must be able to convey a certain sense of verisimilitude, the appearance of true reality. Those employing interviews must faithfully depict the key meanings of the people they interviewed in a way that rings true to those people, even if the end result surprises them. And all researchers must strive for clarity in their publications so that various audiences can understand what was found and why it is important.

The book concludes with a short chapter (chapter 21) discussing the value of qualitative research. At the very end of this book, you will find a glossary of terms. I recommend you make frequent use of the glossary and add to each entry as you find examples. Although the entries are meant to be simple and clear, you may also want to paraphrase the definition—make it “make sense” to you, in other words. In addition to the standard reference list (all works cited here), you will find various recommendations for further reading at the end of many chapters. Some of these recommendations will be examples of excellent qualitative research, indicated with an asterisk (*) at the end of the entry. As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. A good example of qualitative research can teach you more about conducting research than any textbook can (this one included). I highly recommend you select one to three examples from these lists and read them along with the textbook.

A final note on the choice of examples – you will note that many of the examples used in the text come from research on college students. This is for two reasons. First, as most of my research falls in this area, I am most familiar with this literature and have contacts with those who do research here and can call upon them to share their stories with you. Second, and more importantly, my hope is that this textbook reaches a wide audience of beginning researchers who study widely and deeply across the range of what can be known about the social world (from marine resources management to public policy to nursing to political science to sexuality studies and beyond). It is sometimes difficult to find examples that speak to all those research interests, however. A focus on college students is something that all readers can understand and, hopefully, appreciate, as we are all now or have been at some point a college student.

Recommended Reading: Other Qualitative Research Textbooks

I’ve included a brief list of some of my favorite qualitative research textbooks and guidebooks if you need more than what you will find in this introductory text. For each, I’ve also indicated if these are for “beginning” or “advanced” (graduate-level) readers. Many of these books have several editions that do not significantly vary; the edition recommended is merely the edition I have used in teaching and to whose page numbers any specific references made in the text agree.

Barbour, Rosaline. 2014. Introducing Qualitative Research: A Student’s Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. A good introduction to qualitative research, with abundant examples (often from the discipline of health care) and clear definitions. Includes quick summaries at the ends of each chapter. However, some US students might find the British context distracting and can be a bit advanced in some places. Beginning.

Bloomberg, Linda Dale, and Marie F. Volpe. 2012. Completing Your Qualitative Dissertation. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Specifically designed to guide graduate students through the research process. Advanced.

Creswell, John W., and Cheryl Poth. 2018 Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. This is a classic and one of the go-to books I used myself as a graduate student. One of the best things about this text is its clear presentation of five distinct traditions in qualitative research. Despite the title, this reasonably sized book is about more than research design, including both data analysis and how to write about qualitative research. Advanced.

Lareau, Annette. 2021. Listening to People: A Practical Guide to Interviewing, Participant Observation, Data Analysis, and Writing It All Up. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. A readable and personal account of conducting qualitative research by an eminent sociologist, with a heavy emphasis on the kinds of participant-observation research conducted by the author. Despite its reader-friendliness, this is really a book targeted to graduate students learning the craft. Advanced.

Lune, Howard, and Bruce L. Berg. 2018. 9th edition. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Pearson. Although a good introduction to qualitative methods, the authors favor symbolic interactionist and dramaturgical approaches, which limits the appeal primarily to sociologists. Beginning.

Marshall, Catherine, and Gretchen B. Rossman. 2016. 6th edition. Designing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Very readable and accessible guide to research design by two educational scholars. Although the presentation is sometimes fairly dry, personal vignettes and illustrations enliven the text. Beginning.

Maxwell, Joseph A. 2013. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. A short and accessible introduction to qualitative research design, particularly helpful for graduate students contemplating theses and dissertations. This has been a standard textbook in my graduate-level courses for years. Advanced.

Patton, Michael Quinn. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. This is a comprehensive text that served as my “go-to” reference when I was a graduate student. It is particularly helpful for those involved in program evaluation and other forms of evaluation studies and uses examples from a wide range of disciplines. Advanced.

Rubin, Ashley T. 2021. Rocking Qualitative Social Science: An Irreverent Guide to Rigorous Research. Stanford: Stanford University Press. A delightful and personal read. Rubin uses rock climbing as an extended metaphor for learning how to conduct qualitative research. A bit slanted toward ethnographic and archival methods of data collection, with frequent examples from her own studies in criminology. Beginning.