6 A Model of Scientific Research

Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cutler; Dana C. Leighton; and Nobuko Fujita

7

A Model of Scientific Research in Education

Learning Objectives

- Review a general model of scientific research in education

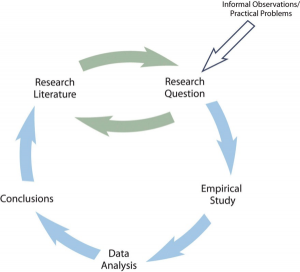

Figure 2.1 presents a simple model of scientific research in education. The researchers formulate a research question, conduct an empirical study designed to answer the question, analyze the resulting data, draw conclusions about the answer to the question, and publishes the results so that they become part of the research literature (i.e., all the published research in that field). Because the research literature is one of the primary sources of new research questions, this process can be thought of as a cycle. New research leads to new questions, which lead to new research, and so on. Figure 2.1 also indicates that research questions can originate outside of this cycle either with informal observations or with practical problems that need to be solved. But even in these cases, the researcher would start by checking the research literature to see if the question had already been answered and to refine it based on what previous research had already found.

The research by Mehl and his colleagues is described nicely by this model. Their research question—whether women are more talkative than men—was suggested to them both by people’s stereotypes and by claims published in the research literature about the relative talkativeness of women and men. When they checked the research literature, however, they found that this question had not been adequately addressed in scientific studies. They then conducted a careful empirical study, analyzed the results (finding very little difference between women and men), formed their conclusions, and published their work so that it became part of the research literature. The publication of their article is not the end of the story, however, because their work suggests many new questions (about the reliability of the result, about potential cultural differences, etc.) that will likely be taken up by them and by other researchers inspired by their work.

As another example, consider that as cell phones became more widespread during the 1990s, people began to wonder whether, and to what extent, cell phone use had a negative effect on driving. Many psychologists decided to tackle this question scientifically (e.g., Collet, Guillot, & Petit, 2010)[1]. It was clear from previously published research that engaging in a simple verbal task impairs performance on a perceptual or motor task carried out at the same time, but no one had studied the effect specifically of cell phone use on driving. Under carefully controlled conditions, these researchers compared people’s driving performance while using a cell phone with their performance while not using a cell phone, both in the lab and on the road. They found that people’s ability to detect road hazards, reaction time, and maintain control of the vehicle were all impaired by cell phone use. Each new study was published and became part of the growing research literature on this topic. For instance, other research teams subsequently demonstrated that cell phone conversations carry a greater risk than conversations with a passenger who is aware of driving conditions, which often become a point of conversation (e.g., Drews, Pasupathi, & Strayer, 2004)[2].

In education, consider how distracting cell phones can be for students in schools. Informal observations from teachers suggest that cellphones be banned from schools. Educational researchers and educational technology stakeholders have responded to calls to ban cell phones, which may be considered curtailment of digital technologies and digital education (Selwyn & Aagard, 2020).

Selwyn and Aagaard (2021) argues that the current to ban cell phones in schools offers an opportunity to advance understandings about several seemingly problematic issues regarding their use in school. In particular, they reconsider concerns that teachers and parents express associated with the ban such as 1) technology addiction; 2) digital distraction; 3) cyberbullying; 4) surveillance capitalism; and 5) environmental sustainability of digital education. The paper highlights evidence that counters popular assumptions of cell phone bans, and highlights the development of more complex, nuanced understandings of complex political and ecological issues surrounding the continued use of digital technologies in schools.

Exercises

- Consider the rules for using cell phones and other mobile devices in Ontario K-12 schools after the provincial code of conduct with stronger rules to help students focus on school that came into effect on September 1st, 2024.

- As a researcher in education, what expert advice would you give to a parent who asks for your expert opinion on the ban?

Video Attributions

- “Understanding driver distraction” by American Psychological Association. Standard YouTube Licence.

- Collet, C., Guillot, A., & Petit, C. (2010). Phoning while driving I: A review of epidemiological, psychological, behavioral and physiological studies. Ergonomics, 53, 589–601. ↵

- Drews, F. A., Pasupathi, M., & Strayer, D. L. (2004). Passenger and cell-phone conversations in simulated driving. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 48, 2210–2212. ↵

- Selwyn, N., & Aagaard, J. (2021). Banning mobile phones from classrooms – An opportunity to advance understandings of technology addiction, distraction, and cyberbullying. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(1). 8-19. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12943

Media Attributions

- Screenshot 2025-02-12 at 8.26.57 PM