1.2 The skills needed in a digital age

![]()

![]()

Knowledge involves two strongly inter-linked but different components: content and skills. Content includes facts, ideas, principles, evidence, and descriptions of processes or procedures. Most instructors, at least in universities, are well trained in content and have a deep understanding of the subject areas in which they are teaching. Expertise in skills development though is another matter. The issue here is not so much that instructors do not help students develop skills – they do – but whether these intellectual skills match the needs of knowledge-based workers, and whether enough emphasis is given to skills development within the curriculum.

The skills required in a knowledge society include the following (adapted from Conference Board of Canada, 2014):

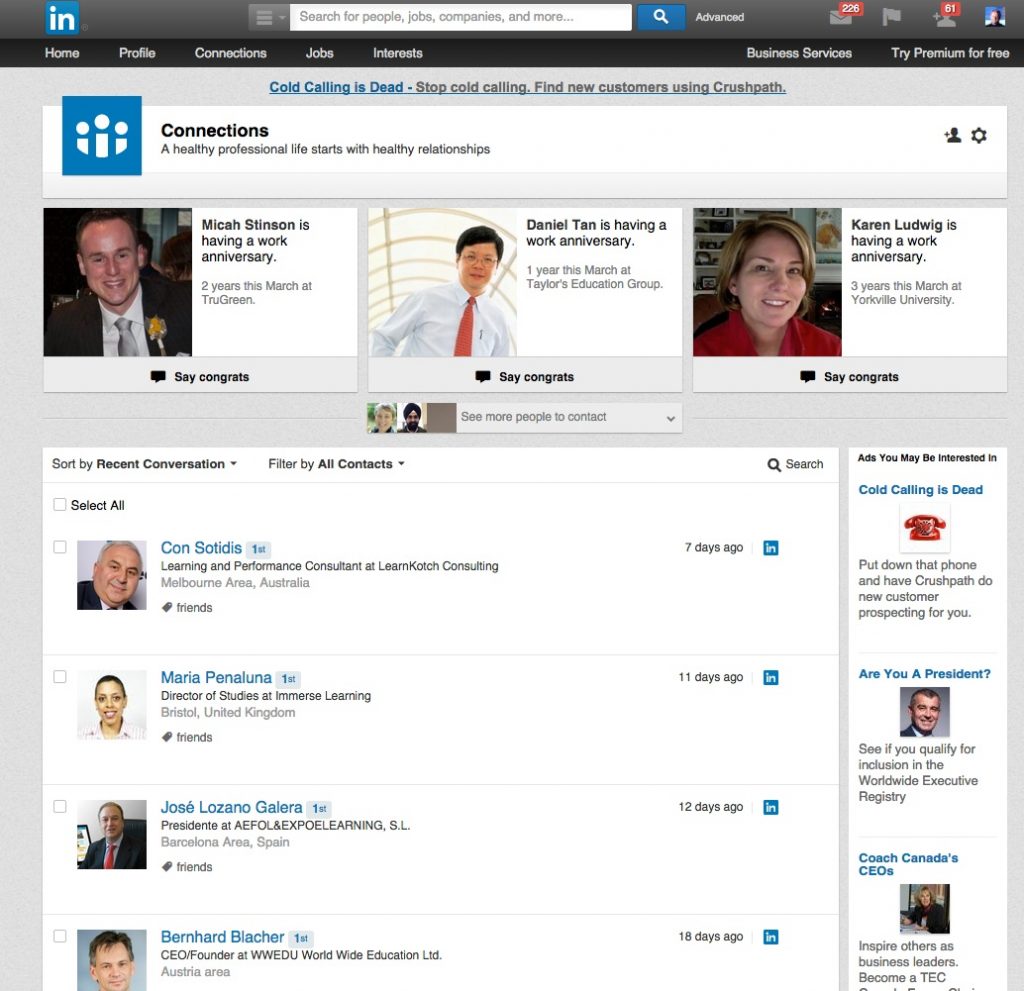

- communications skills: as well as the traditional communication skills of reading, speaking and writing coherently and clearly, we need to add social media communication skills. These might include the ability to create a short YouTube video to capture the demonstration of a process or to make a sales pitch, the ability to reach out through the Internet to a wide community of people with one’s ideas, to receive and incorporate feedback, to share information appropriately, and to identify trends and ideas from elsewhere;

- the ability to learn independently: this means taking responsibility for working out what you need to know, and where to find that knowledge. This is an ongoing process in knowledge-based work, because the knowledge base is constantly changing. Incidentally I am not talking here necessarily of academic knowledge, although that too is changing; it could be learning about new equipment, new ways of doing things, or learning who are the people you need to know to get the job done;

- ethics and responsibility: this is required to build trust (particularly important in informal social networks), but also because generally it is good business in a world where there are many different players, and a greater degree of reliance on others to accomplish one’s own goals;

- teamwork and flexibility: although many knowledge workers work independently or in very small companies, they depend heavily on collaboration and the sharing of knowledge with others in related but independent organizations. In small companies, it is essential that all employees work closely together, share the same vision for a company and help each other out. In particular, knowledge workers need to know how to work collaboratively, virtually and at a distance, with colleagues, clients and partners. The ‘pooling’ of collective knowledge, problem-solving and implementation requires good teamwork and flexibility in taking on tasks or solving problems that may be outside a narrow job definition but necessary for success;

- thinking skills (critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, originality, strategizing): of all the skills needed in a knowledge-based society, these are some of the most important. Businesses increasingly depend on the creation of new products, new services and new processes to keep down costs and increase competitiveness. Universities in particular have always prided themselves on teaching such intellectual skills, but the move to larger classes and more information transmission, especially at the undergraduate level, challenges this assumption. Also, it is not just in the higher management positions that these skills are required. Trades people in particular are increasingly having to be problem-solvers rather than following standard processes, which tend to become automated. Anyone dealing with the public needs to be able to identify needs and find appropriate solutions;

- digital skills: most knowledge-based activities depend heavily on the use of technology. However the key issue is that these skills need to be embedded within the knowledge domain in which the activity takes place. This means for instance real estate agents knowing how to use geographical information systems to identify sales trends and prices in different geographical locations, welders knowing how to use computers to control robots examining and repairing pipes, radiologists knowing how to use new technologies that ‘read’ and analyze MRI scans. Thus the use of digital technology needs to be integrated with and evaluated through the knowledge-base of the subject area;

- knowledge management: this is perhaps the most over-arching of all the skills. Knowledge is not only rapidly changing with new research, new developments, and rapid dissemination of ideas and practices over the Internet, but the sources of information are increasing, with a great deal of variability in the reliability or validity of the information. Thus the knowledge that an engineer learns at university can quickly become obsolete. There is so much information now in the health area that it is impossible for a medical student to master all drug treatments, medical procedures and emerging science such as genetic engineering, even within an eight year program. The key skill in a knowledge-based society is knowledge management: how to find, evaluate, analyze, apply and disseminate information, within a particular context. This is a skill that graduates will need to employ long after graduation.

We know a lot from research about skills and skill development (see, for instance, Fischer, 1980, Fallow and Steven, 2000):

- skills development is relatively context-specific. In other words, these skills need to be embedded within a knowledge domain. For example, problem solving in medicine is different from problem-solving in business. Different processes and approaches are used to solve problems in these domains (for instance, medicine tends to be more deductive, business more intuitive; medicine is more risk averse, business is more likely to accept a solution that will contain a higher element of risk or uncertainty);

- learners need practice – often a good deal of practice – to reach mastery and consistency in a particular skill;

- skills are often best learned in relatively small steps, with steps increasing as mastery is approached;

- learners need feedback on a regular basis to learn skills quickly and effectively; immediate feedback is usually better than late feedback;

- although skills can be learned by trial and error without the intervention of a teacher, coach, or technology, skills development can be greatly enhanced with appropriate interventions, which means adopting appropriate teaching methods and technologies for skills development;

- although content can be transmitted equally effectively through a wide range of media, skills development is much more tied to specific teaching approaches and technologies.

The teaching implications of the distinction between content and skills will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 2. The key point here is that content and skills are tightly related and as much attention needs to be given to skills development as to content acquisition to ensure that learners graduate with the necessary knowledge and skills for a digital age.

Activity 1.2 What skills are you developing in your students?

1. Write down a list of skills you would expect students to develop as a result of studying your courses.

2. Compare these skills to the ones listed above. How well do they match?

3. What do you do as an instructor that enables students to practice or develop the skills you have identified?

References

The Conference Board of Canada (2014) Employability Skills 2000+ Ottawa ON: Conference Board of Canada

Fallow, S. and Stevens, C. (2000) Integrating Key Skills in Higher Education: Employability, Transferable Skills and Learning for Life London UK/Sterling VA: Kogan Page/Stylus

Fischer, K.W. (1980) A Theory of Cognitive Development: The Control and Construction of Hierarchies of Skills Psychological Review, Vol. 84, No. 6