The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

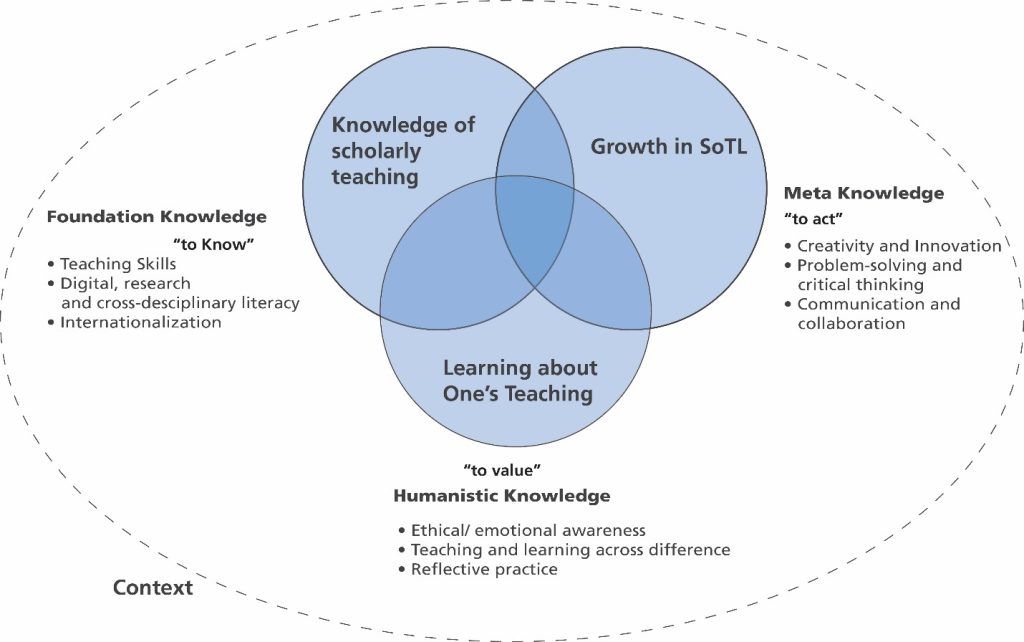

To be a learned scholar of the art of teaching requires thoughtful, intentional, and ongoing analysis of the teaching and learning process. You must recognize that the scholarship of teaching and learning is central to the delivery of high-quality curriculum and student engagement in applied, collaborative learning. At Centennial, the Framework for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) provides context for this work (Figure 1)

Adapted from: Randall, N., Heaslip, P., & Morrison, D. (2013). Campus-based educational development & professional learning: Dimensions & directions. Vancouver, BC: BCcampus; Kereluik, K., Mishra, P., Fahnoe, C., & Terry, L. (2013). What knowledge is of most worth: Teacher knowledge for 21st century learning. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 29(4), 127-140.

The SoTL includes three overlapping and dynamic elements of teaching/learning practice: (1) knowledge of scholarly teaching; (2) learning about one’s teaching; and (3) growth in SoTL. The three domains are represented in a Venn diagram illustrating points of intersection and overlap. The framework incorporates:

- Foundation knowledge – what faculty “know” – demonstrated through teaching skills, research, cross-disciplinary literacy, and capacity to internationalize and Indigenize curriculum.

- Humanistic knowledge – what faculty “value” – inherent characteristics that impact teaching and learning such as ethical and emotional awareness, cultural humility, and ongoing reflexivity.

- Meta-knowledge – how faculty “act” – skills and abilities such as creativity and innovation, problem solving and critical reflection, and communication and collaboration across disciplines.

To understand what we mean by ‘scholarship’ within this framework, it is helpful to look to Boyer’s Model of Teaching and Scholarship and its broader definition of scholarship. According to Boyer, there are four types of scholarship:

- Discovery: traditional view of scholarship, primary research, quantitative and qualitative data collection, analysis and dissemination.

- Integration: interdisciplinary collaboration, critical analysis, review of knowledge, synthesis of views.

- Application: knowledge and skills applied to the solution of societal needs and practice gaps.

- Teaching: sharing knowledge, reflective analysis of teaching and learning, the product of the scholarships of discovery, integration, and application.

Boyer recognizes these types of scholarship as equal forms of scholarly inquiry (Healey, 2000, Richlin, 2001). By acknowledging these forms of scholarship as equal counterparts, Boyer has transformed the ways in which faculty understand scholarship and research, and engage together as a community of learners and scholars. In relation to the SoTL, Boyer argued that good teaching in itself needs to be better understood, open to critique, and shared with others (Boyer, 1991 in Healey, 2001).

While teaching is defined as “making student learning possible”, scholarly teaching is defined as “making transparent how we have made learning possible” (Ramsden, 1992, in Healey, 2001). Faculty who engage in scholarly teaching do so explicitly through the three domains of the SoTL framework:

- knowledge of scholarly teaching (“engaging with the scholarly contributions of others on teaching and learning”).

- awareness and reflection on one’s own teaching practice.

- growth in SoTL (“communication and dissemination of aspects of practice and theoretical ideas about teaching and learning in general, and teaching and learning within the discipline”) (Healey, 2001:171).

In short, a scholarship for teaching is fostered when faculty are able to share their work publicly, receive critique or peer review, and engage in knowledge exchange with their peers and other professional communities (Shulman, 2000 in Luddeke, 2003).

So where do you go next? How can you as a faculty member begin to engage in scholarly teaching? How can you inform, evaluate, and plan your personal journey through the SoTL while exploring and contributing to scholarship as envisioned by Boyer? Consider the power and utility of reflective practice!