5.4: The Procurement Life Cycle in Canada and the World

Overview

Public procurement accounts for around one-fifth of global gross domestic product (GDP). In most high-income economies, the purchase of goods and services accounts for a third of total public spending, and in developing economies, about half. Given its size, the public procurement market can improve public sector performance, promote national competitiveness and drive domestic economic growth. Moreover, it can boost economic development. However, the benefits go beyond getting value for money and other monetary goals. Today, public procurement addresses policy objectives such as promoting sustainable and green procurement. Integrated with procurement policy are social objectives to support enterprises owned by disadvantaged groups and promote small and medium enterprises.

Internationally accepted good practices must be measure across various phases of the public procurement life cycle: preparing, submitting and evaluating bids, and awarding and executing contracts. Impediments to a well-functioning procurement system can arise throughout the different phases of the cycle. Private firms’ participation in the public market may be affected by issues of transparency and efficiency as early as the identification of a need by a procuring entity and can expand throughout the final execution of a service.

The Procurement Life Cycle

Unnecessary hurdles and obstacles to efficiency can occur at every step of the procurement life cycle. Each step comes with its own set of risks, but the lack of transparency, bottleneck regulations, unexpected delays and unequal access to information are challenges that suppliers can face all the way from the need assessment phase to awarding and implementing the procurement contract. Through targeted policies and strict implementation of regulations, governments have an important role in making the overall process easier for companies. Generally, international good practices can be used as goals when designing procurement policies. But beyond the guiding principles of transparency, efficiency and fairness that are beneficial to all regimes, governments must look into the specificities of their own system, identify risks and opportunities, and adopt targeted rules that will address these risks and make their systems stronger.

Transparency and access to information remain a priority in each stage of the procurement process, from the first conception of the procuring entity’s need, through contract award and all the way to final delivery and payment.

Ensuring that suppliers can easily become aware of tendering opportunities, obtain copies of tender documents, and understand how and on what grounds bids are evaluated are just a few examples of how policymakers can make procurement regimes more transparent. Transparent processes, easy access to information and open procurement markets drive down costs, improve quality and provide better value for money. They also lower the risk that any party will be improperly advantaged due to flaws in the system. Conversely, when it is difficult or costly to obtain information on the government’s needs, technical specifications and processes for submitting and evaluating bids, the procurement system is drained of efficiency, transaction costs rise, and potential bidders may be excluded from participating.

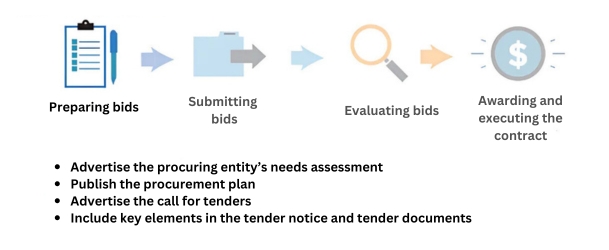

Preparing Bids

When assessing their needs and researching potential solutions, procuring entities often need to consult with the private sector to determine the solutions available, a process called market research. Early communication with the private sector often shapes the procurement, most notably the technical specifications required in the tender documents. If one or only a few suppliers are consulted during the market research, other suppliers may not be able to submit offers that comply with the technical specifications. This limits not only competition but also the procuring entity’s ability to consider the full menu of options available, and thus the opportunity to get the best value for public money. After its market research the procuring entity chooses the appropriate procurement mechanisms to conduct its procurement and specify clear technical specifications for the evaluation of offers. To ensure that potential suppliers are encouraged to compete, certain baseline information has to be included in tender documents, and a notice of tender is to be advertised, preferably through multiple channels and ideally through a central online procurement portal. These documents should be available as early as possible, if not immediately after they are final, and they should be free. Various elements of the preparation period can weigh heavily on a supplier’s decision to respond to a call for tender. Easy access to a procurement plan is critical for anticipating and planning the preparation of a proposal.

Detailed tender specifications—clearly stating the requirements to meet and the assessment method used by the procuring entity in evaluating proposals—are essential for a supplier to gauge its chances of winning the contract. Exhibit 5.2 captures elements of the procurement life cycle that take place until a supplier submits a bid.

Calibrated data points measure the ease with which prospective bidders become aware of tendering opportunities, make an informed decision on whether to submit a bid, and acquire the information and material necessary to prepare a proposal.[1]

Advertise the Procuring Entity’s Needs Assessment

During the needs assessment phase, the procuring entity can engage the private sector to assess the procuring entity’s needs—the type of good or service needed, the quantity and the technical specifications—before drafting the tender notice.[2] To provide an equal opportunity to all firms and potential bidders, it should publicly advertise any interaction with the private sector during market research. Such advertisement promotes the transparency and integrity of the procurement process. Companies in Argentina or Brazil are able to participate in a preliminary consultation process for all interested parties to provide their input on the technical specifications of the procurement, under certain conditions. Indeed in Argentina, when the amount of the contract or the complexity of the procurement is very high, a call for consultation is published online for a minimum of 10 days and allows any person to submit comments.[3] In Brazil a public consultation is mandatory 15 days before publishing the tender documents for high-value construction and engineering contracts. Algeria, Canada, Chile, Poland and Taiwan also require publicly advertised consultations with the private sector during market research. In Canada, Chile and Taiwan consultations with the private sector are always required to be public, and notices are published online to reach a wide audience. In Poland, the procuring entity must publish a notice online and include information on the consultations in the tender documents.[4]

Publish the Procurement Plan and Advertise the Call for Tenders

To promote transparency and help bidders identify upcoming tendering that might interest them and grant them more time to prepare a viable offer, procuring entities should be required to publish their procurement plan.

More importantly, widely advertising the call for tenders is essential to attract a maximum number of offers and guarantee private sector suppliers access to tendering opportunities. In its Methodology for Assessing Procurement Systems (MAPS), the OECD promotes the publication of open tenders “in at least a newspaper of wide national circulation or on a unique official Internet site, where all public procurement opportunities are posted that is easily accessible.”[5] Channeling information to private companies on the Web is generally a good practice. But in countries where internet access can pose a challenge for users, especially SMEs and other bidders with few resources, governments may allow for a transition period so that the tendering information and materials remain accessible through traditional communication channels. With online procurement platforms, the legal framework in many economies has been revised to require only online publication. However, many economies continue to broadcast calls for tenders through traditional channels. Indeed, traditional channels provide information in countries where SMEs have less capacity and less access to online portals.

In a few economies, the transition to electronic communication support has started but not been completed. In Mozambique and Sierra Leone users can click on a link to access tender notices, with projects updated on a daily basis.

Include Key Elements in the Tender Notice and Tender Documents

To make an informed decision on whether to respond to a call for tender, a company needs easy access to the requirements to meet and to the criteria the procuring entity will use to assess bids. Both elements should be included either in the tender notice or in the tender documents. When they are available only in tender documents, they should be freely accessible. According to the OECD’s MAPS the “content of publication” should include “sufficient information to enable potential bidders to determine their ability and interest in bidding.”[6]

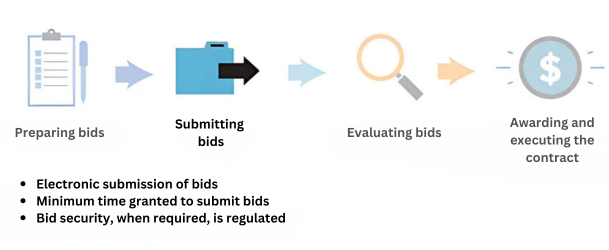

Submitting Bids

For a small company, several elements come into play between the moment a call for tender is advertised and the moment it submits a bid in response to the call. Before anything else, the company must decide whether to participate in the tendering. If it decides to do so, it must properly prepare and submit its bid and comply with the timeframe and specifications that the procuring entity imposes. The regulatory framework can substantially ease the tasks for prospective bidders. For instance, making it mandatory for the entity to address bidders’ questions on technical specifications in a timely fashion guarantees better access to information. Ensuring that the answers that are not specific to one bidder are shared with all bidders levels the playing field and conveys the notion that they are treated fairly and equally. By the same token, requiring that tender documents be distributed for free or at a regulated price prevents excessive transaction costs that could deter participation. The regulatory framework can also prevent unnecessary hurdles for prospective bidders when it comes to bid submission. In countries where accessing the internet is not challenging, the ability to submit a bid online facilitates the process for bidders. Imposing a maximum amount of bid security that the procuring entity can request from bidders also helps prevent excessive administration costs and deters participation from suppliers that are not serious candidates. Allocating a reasonable time to submit a bid is an important element for bidders.

Exhibit 5.3 shows how regulatory framework and procedures facilitate bidders’ access to information while preparing their bids and ease the bid submission process.[7]

Electronic Submission of Bids

Using electronic means to conduct public procurement is widely perceived as a step toward procurement efficiency. It increases access to tendering opportunities, eases compliance with procedures and reduces transaction costs for bidding firms. The submission of bids through an electronic portal is only one of the options available on an online portal. For bidders, submitting a bid online offers a safer option for delivering proposals efficiently. Except for a few countries like Chile and the Republic of Korea, where electronic submission of bids has become the rule, e-bidding is possible only in limited circumstances in most economies measured. In Poland the ability to submit a bid online is contingent on the procuring entity’s approval. E-bidding can also be possible for just a few government agencies, as in Hong Kong SAR, China, where only one government department can receive bids online. Restrictions can also apply to bidders. In the United States a company has to go through an authorization process to bid online. As a result, e-bidding mandated at the national level and across all procuring entities remains the exception for open calls for tender. In addition to online submissions, sending a bid by email is another efficient option to reduce transaction costs for bidders.

Minimum Time to Submit Bids

Granting suppliers enough time to prepare and submit their bids can ensure fairness, especially for SMEs as preparing a bid can require hiring consultants, preparing plans, producing samples and performing other time-consuming tasks. If the timeframe to do so is too short, smaller companies have less chance to meet the deadline and submit a solid proposal. But for efficiency the timeframe should not be excessive either.

Policy makers thus have to strike the right balance between fairness and efficiency in determining the bidding timeframe, taking the reliability of the postal system into account versus online platforms and email. The 2014 European Union directive on public procurement shows that a longer timeframe to submit a bid is not necessarily better. Indeed, the directive lowered the minimum time for suppliers to submit a bid for procurement. The timeframe is now 15 to 52 days depending on the type of bid process.

Bid Security, When Required, Is Regulated

Bid security is an efficient instrument for procuring entities to ensure that they receive only serious offers, which bidders will maintain until the selection is made. On the amount of bid security, there is no internationally accepted good practice. The amount should be substantial enough that it deters suppliers from submitting frivolous offers. But when the amount of the bid security is too high, it can deter potential bidders. Since the amount of bid security adds to the cost of submitting a bid, expensive bid security can deter SMEs and other bidders with limited resources. Procuring entities may thus strike a balance in determining what’s appropriate. The law can also provide a list of acceptable forms of bid security and mandate that bidders, not procuring entities, can choose the form that best suits them.

Evaluating Bids

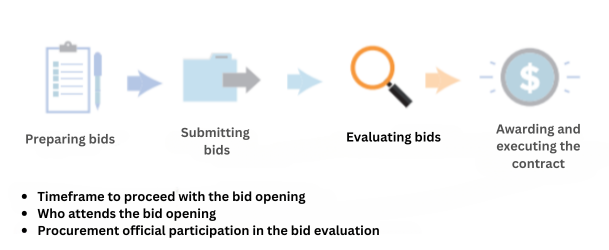

The bid opening session should be transparent, and the bid evaluation should follow the technical specifications and other award criteria detailed in the tender documents. But if the legal framework does not provide clear enough guidance, or if the procuring entity is not transparent enough about how bids are evaluated, suppliers can perceive the evaluation phase as a subjective decision to select the supplier it prefers to do business with. If this perception is allowed to persist, suppliers may lose faith in the system’s integrity, feeling that the process is rigged against them and they may ultimately opt out of the procurement market. The regulations should describe the bid opening process, such as specifying which parties can attend the bid opening sessions and whether any aspects of it will be recorded. Exhibit 5.4 looks at whether the bid evaluation is open, transparent and fair to guarantee bidders that the process follows the best standards of transparency.[8]

Timeframe to Proceed with the Bid Opening

The legal framework in half the economies surveyed requires the bid opening session immediately after the closing of the bid submission period—or indicates the timeframe for the bid opening session to take place. In Bolivia, a company can refer to the mandatory timeline determined by the procuring entity for each procurement, which states the date, time and place for the bid opening session. In Spain, it knows the exact date, time and place of the bid opening session, but that can be up to 30 calendar days after the closing of the bid submission period. In Australia, Jamaica, Namibia or Sweden, the legal framework is vague and guarantees only that the session takes place as soon as possible or practicable. In Afghanistan, Cameroon and Morocco, a company has, in practice, no guarantee that the procuring entity will comply with the law and respect the time imposed to proceed with the bid opening.

Who Attends the Bid Opening

To ensure the transparency of the competitive bidding system, all bidders or their representatives should be able to attend the bid opening session. Many economies allow the presence of bidders and their representatives at the bid opening and some are open to the public. In cases where procurement is conducted electronically, as in Chile, the Republic of Korea, the Netherlands and Taiwan, China the electronic bid opening can be conducted without the bidders. But in these instances, bidders can be notified electronically of the opening of their bids. In the Netherlands a company would systematically receive an automatic electronic notification when its bid is opened. In Chile the bid opening is conducted automatically, through the information system, on the day and time established in the notice of invitation to tender and in the tender documents. The information system provides the bidders with information about the session. In such cases a company could attend the bid opening in person. In Canada, Hong Kong SAR, China, Ireland, Lebanon and Malaysia, the regulatory framework is silent on who can attend the bid opening session.

Procurement Official Participation in the Bid Evaluation

Once the bid evaluation is underway, the bidder will want to know whether the best person possible has been appointed to evaluate bids. It knows that in some economies, public officials involved in the initial stages of the procurement cannot take part in the evaluation. To guarantee the efficiency of the bid evaluation, the procurement official conducting the needs assessment and drafting the technical specifications should not be prevented from participating in the bid evaluation. Indeed, if procuring officials are prevented from participating in any procurement, there is a real danger of excluding the most qualified officials from the bid evaluation. There are also benefits from having an integrated evaluation team.

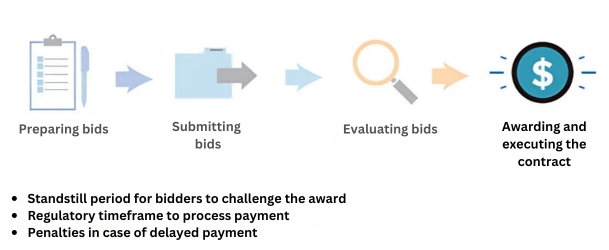

Awarding and Executing Contracts

Once the bidder that best satisfies the technical specifications and award criteria is identified, the contract has to be awarded promptly and transparently. The legal framework should require that a contract award be published, as stated in Article 23 of UNCITRAL Model Law on Public Procurement. In addition, losing bidders should be informed of the award and given an opportunity to learn why they did not win. Awarding the contract is the end of the formal procurement process, but the contract must still be managed, and the supplier must be paid in return for its performance. Many procurement systems do not cover this phase of the procurement life cycle. Indeed, even internationally accepted procurement models—such as the World Trade Organization’s Revised Agreement on Government Procurement and the UNCITRAL Model Law on Public Procurement—do not provide guidance or good practices for contract management. The legal framework should specify a timeframe for making payments and provide additional compensation when the procuring entity fails to pay on time. Indeed, delays in payment can have severe consequences for private sector suppliers, particularly SMEs, which typically do not have large cash flows. Exhibit 5.5 assesses whether, once the best bid has been identified, the contract is awarded transparently and the losing bidders are informed of the procuring entity’s decision.[9]

Once the execution of the contract is taking place, the procuring entity should be encouraged to manage the payment process through an online system, offering the possibility for the supplier to sign the contract and request payments online. It should also comply with clear regulations when it comes to paying the supplier on time—and specify penalties for delayed payment.

Standstill Period for Bidders to Challenge the Award

A standstill period—between announcing a potential awardee and signing the contract— ensures that bidders have enough time to examine the award and decide whether to initiate a review procedure. This is particularly important in economies where an annulment of the contract is not possible,[10] or when a complaint does not trigger a suspension of the procurement process. In accord with UNCITRAL the period should be long enough to file any challenge to the proceedings, but not so short as to interfere unduly with the procurement.[11] A minimum of 10 days is a recognized standstill period, as reflected in judgments by the European Union Court of Justice,[12] and the WTO’s Government Procurement Agreement. The standstill period and the time limits for the review body should be synchronized.[13]

Regulatory Timeframe to Process Payment

A company has fulfilled its contractual obligations and submitted a request for payment to the procuring entity. It is now waiting to be paid for services rendered. It knows that an efficient public procurement system processes payments to suppliers within a limited number of calendar days once a request for payment is submitted. In Poland, in compliance with the 2014 European Union directive on public procurement, the company is guaranteed payment within 30 days of the date of issuing certificates of works or documenting performance, as per the law.[14]

In several economies, delays of more than 30 days are common in practice. In many economies, suppliers have to wait longer than 60 calendar days for payment. In Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, The Gambia, Honduras, Mozambique, Mauritius, Nepal, Serbia, Turkey and Vietnam a company can find the payment schedule and forms in the contract. But in some economies, payment processing takes more than 30 days. The two most prominent reasons are the length of administrative procedures and budgetary constraints. In Senegal a company receives payment within 15 days of submitting its request.[15] But in Kenya the procuring entity has to process the payment in 30 days if the said company is owned by youths, women or persons with disabilities.[16]

Penalties in case of Delayed Payments

Many economies do not mandate procuring entities to pay penalties to suppliers in cases of late payment. A company is entitled to receive penalties if the procuring entity fails to pay on time in two-thirds of the economies surveyed. In Canada it automatically receives interest when an account is overdue.[17] Even in economies where penalties are legally granted to suppliers, half do not follow their laws in practice, including many in Europe and Central Asia and in Latin America and the Caribbean. In Mexico a supplier would probably see, as part of the procurement contract, provisions for penalties if payment is delayed. Even so, the entitled suppliers rarely request such penalties.

Checkpoint 5.4

Image Descriptions

Exhibit 5.2: The image is a flowchart illustrating the process of preparing bids. The chart is composed of four stages represented by icons and text, connected by arrows pointing to the right. The first stage shows a clipboard icon labeled “Preparing bids.” The second stage has a folder icon labeled “Submitting bids” in gray text. The third stage displays a magnifying glass icon labeled “Evaluating bids” in gray text. The final stage features a dollar sign inside a circle, labeled “Awarding and executing the contract” in gray text. Below the flowchart is a list of tasks in bullet points under preparing bids, including advertising the procuring entity’s needs, publishing the procurement plan, advertising the call for tenders, and including key elements in tender documentation.

[back]

Exhibit 5.3: The image is a visual representation of a bid submission and evaluation process in project procurement. It features a linear flowchart consisting of four main steps. The first step, “Preparing bids,” shows a clipboard with a piece of paper and a pen. The next icon is a blue briefcase with a black arrow, signifying “Submitting bids.” This section highlights that electronic submissions are possible, a minimum submission time is regulated, and bid security may be required. The third step, “Evaluating bids,” is depicted by a magnifying glass. Finally, the last step, “Awarding and executing the contract,” is represented by a circular icon with a dollar sign, suggesting financial elements. Each step is labeled below its respective icon.

[back]

Exhibit 5.4: The image presents a flowchart illustrating the bid submission and evaluation process. It consists of a horizontal sequence of icons, each representing a step in the process, with adjacent text labels. From left to right, the steps include: “Preparing bids,” depicted by a clipboard icon; “Submitting bids,” shown with a briefcase icon; “Evaluating bids,” highlighted in orange with a magnifying glass icon; and “Awarding and executing the contract,” represented by a dollar sign inside a circle. Below the main icons, three bullet points detail specific aspects of the “Evaluating bids” step: the timeframe for bid opening, who attends the bid opening, and the participation of procurement officials in the bid evaluation. The overall color scheme is light blue and orange, with the “Evaluating bids” step prominently emphasized.

[back]

Exhibit 5.5: The image is a flowchart illustrating the bid process. It consists of four main stages represented by icons and captions from left to right: “Preparing bids” features a clipboard; “Submitting bids” shows a briefcase; “Evaluating bids” is depicted with a magnifying glass; and “Awarding and executing the contract” is represented by a dollar sign in a circle. Below these stages, three bullet points detail key aspects of the final step: a standstill period for challenges, regulatory timeframe for payments, and penalties for delayed payments.

[back]

Attributions

“5.4: The Procurement Life Cycle in Canada and the World” is adapted from Benchmarking Public Procurement 2016: Assessing Public Procurement Systems in 77 Economies by the World Bank Group (2016), licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO License except where otherwise noted.

Exhibits 5.2, 5.3, 5.4, and 5.5 are taken from Benchmarking Public Procurement 2016: Assessing Public Procurement Systems in 77 Economies by the World Bank Group (2016), licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO License, except where otherwise noted.

The multiple choice questions in the Checkpoint boxes were created using the output from the Arizona State University Question Generator tool and are shared under the Creative Commons – CC0 1.0 Universal License.

Image descriptions and alt text for the exhibits were created using the Arizona State University Image Accessibility Creator and are shared under the Creative Commons – CC0 1.0 Universal License.

- The thematic coverage of the subindicator is broader than is presented here, and additional data points are available on the Benchmarking Public Procurement website (http://bpp.worldbank.org). ↵

- Or any other governmental entity conducting the needs assessment ↵

- Article 32 of Executive Decree No. 893/2013 on Public Procurement of Argentina. ↵

- Article 31 of the Public Procurement Law of Poland, as amended in 2014. ↵

- OECD 2010 ↵

- Idem. ↵

- The thematic coverage of the subindicator is broader than is presented here, and additional data points are available on the Benchmarking Public Procurement website (http://bpp.worldbank.org) ↵

- The thematic coverage of the subindicator is broader than is presented here, and additional data points are available on the Benchmarking Public Procurement website (http://bpp.worldbank.org). ↵

- The thematic coverage of the subindicator is broader than is presented here, and additional data points are available on the Benchmarking Public Procurement website (http://bpp.worldbank.org). ↵

- UNCTAD 2014 ↵

- Idem. ↵

- Case C81/98 Alcatel Austria and Others v Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Verkehr, and C212/02 Commission v Austria. ↵

- OECD 2007b. ↵

- Article 8 of the Act on Payment Terms in Commercial Transactions of 8 March 2013. ↵

- Article 104 of the Public Procurement Law of Senegal. ↵

- Regulation 34 of the Public Procurement & Disposal (Amendment) Regulations of Kenya, 2013. ↵

- Section 4.70.30.1 of the PWGSC Supply Manual of Canada ↵

The procurement life cycle starts with the need assessment by the procuring entity and ends with the execution of the contract.

The framework that comprises all public procurement laws and regulations, legal texts of general application, binding judicial decisions and administrative rulings in connection with public procurement.

Security required from suppliers by the procuring entity to secure the fulfillment of obligations. Examples include bank guarantees etc.