10.2: Types of Risks and Disruptions

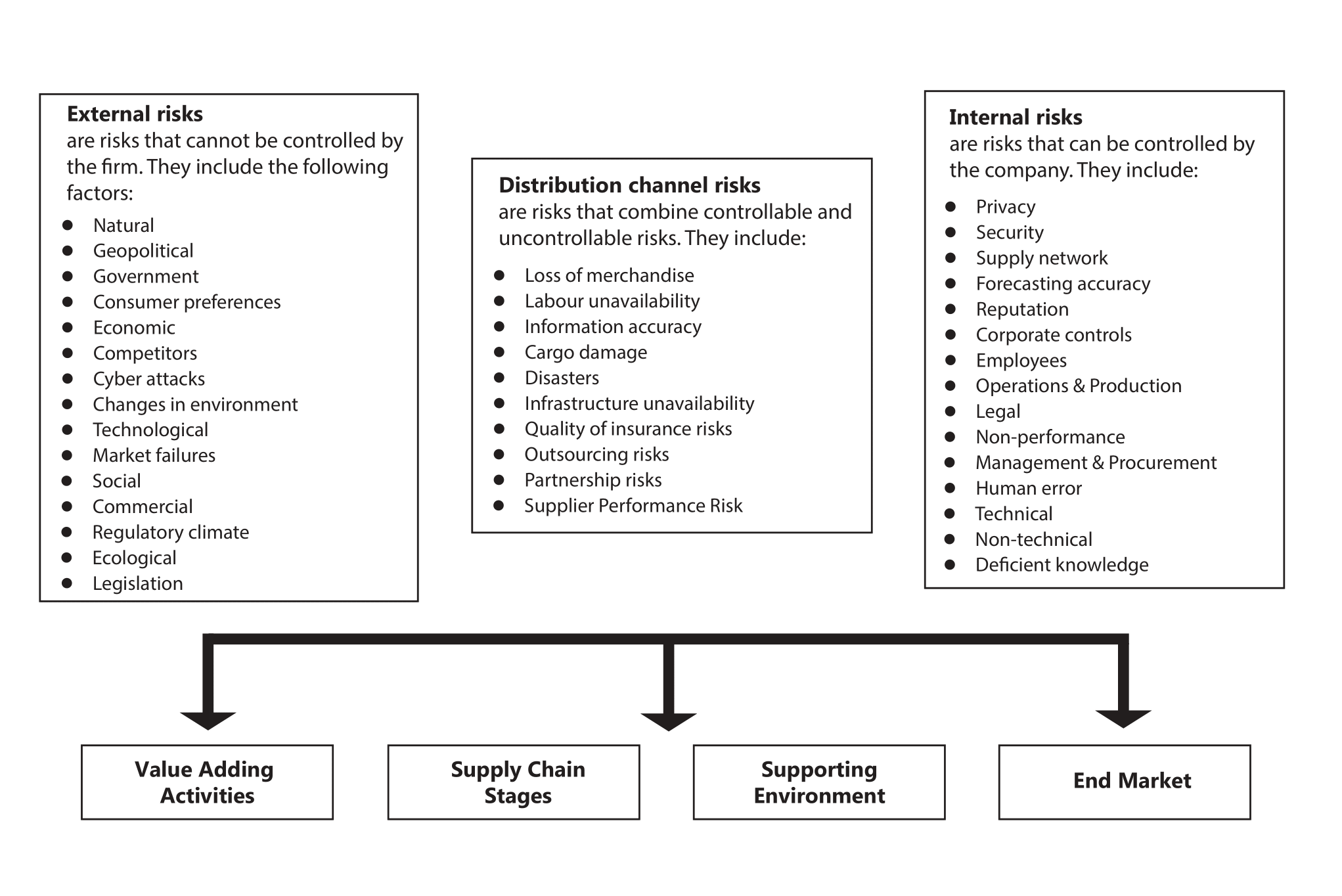

Risk is the possibility of an event that can occur and affect the supply chain. There are different types of risks: external and internal, as well as distribution channel risks. These risks can be predictable, unpredictable, controllable, uncontrollable, technical, or non-technical. Some combine a few criteria, such as predictable and uncontrollable or unpredictable and uncontrollable. External risks are risks that the firm cannot control and often are difficult to influence. Such risks require a complex approach when it comes to identifying and mitigating them.

According to the FITT (2013), external risks can be predictable and uncontrollable. Such risks include cost fluctuations, market risks, inflation, and environmental, operational, and taxation risks. External risks can also be unpredictable and uncontrollable, such as natural hazards and sabotage, which are uncontrollable (FITT, 2013).

Internal risks are risks that the company can control, and they are technical and non-technical. These risks are controllable because the organization can eliminate or avoid them. For example, non-technical internal risks are human error, management delays, inappropriate procurement, or loss of profits (FITT, 2013). Non-technical risks are related to the interactions between stakeholders such as the public, government, regulatory partners, contractors, and communities. Technical internal risks consist of risks associated with technology and design issues. These risks impact the following parts of the organizational model of the global supply chain: value-adding activities, supply chain stages, supporting environment, and end markets such as buyer, producer, or geographic market (Smorodinskaya et al., 2021).

Risks in the global supply chain significantly influence domestic and international companies and environmental organizations overall.

The most identified risks in the global value chain are politics, accidents, natural disasters, product integrity, physical supply security (theft), cybersecurity, financial supply chain, and performance risks (Supply Chain Risk, 2020, February 18).

Exhibit 10.1 categorizes and outlines the most common supply chain risks.

Supply Chain Risks

Here is a clear explanation of Supply Chain Risk Management adapted from Amulya Gurtu & Jestin Johny’s Supply Chain Risk Management: Literature Review.

Risks cause disruption, which ripples through the network of the supply chains. Supply Chain Risk Management [SCRM] ensures the smooth functioning of supply chains. Risk can be labelled as vulnerability, uncertainty, disruption, disaster, peril, or hazard. A lack of foresight about a likely disruption in a supply chain and its causes makes a supply chain vulnerable and the SCM leaders less effective.

SCRM can be divided into two broad approaches. The first is a comprehensive risk management approach, and the second is a focused approach to a specific disruption. These specific disruptions could be security, lead times, or terrorism. For instance, in 2007, a supplier for Mattel toys used lead-based paint without Mattel’s knowledge. This caused disruptions in Mattel’s supply chains. Mattel set up quality assurance centres at the suppliers’ factories to avoid repeating the lead paint crisis. The supplier used lead-based paint to save small operational costs. The cost of disruption to Mattel was much more significant and could have been avoided.

Disruptions in supply chains are evolving to be more comprehensive and recurrent in the business environment. The scale and rate of risk events in the supply network are increasing. Disruptions determine the robustness of SCM in a company. Disruption events are described as when “the tornado hits, the bomb explodes, a supplier goes out of business, or the union begins a wildcat strike” (Sheffi & Rice, 2005). There are different types of risk identified by various academicians and practitioners from the field of SCM.

Some other parameters to classify risks in SCM are: (i) based on the sources of risk and mitigation strategies, (ii) as organizational risks, environmental risks, and network risks, (iii) demand and supply risks, (iv) industry and organizational risks, and (v) network risks.

An uncertain business environment causes supply chain risks. Uncertain business environments result from cyclical business behaviour, fluctuation in demands, or a disaster. Therefore, uncertainty may be seen as a risk that can disrupt supply chain performance. Some authors have categorized supply chain risks under operational, network, and external risks. Operational risks are due to a strategic re-engineering failure within the system. For example, a ferry named Moby Prince collided with a ship named Agip-Abruzzo in the Mediterranean Sea on 10 April 1991, causing a loss of 140 lives and 25,000 tons of oil. Network risks are derived from the supplier’s layers of network based on the title, vendor strategies, and agreements between the supply chain network vendors.

Thirdly, external risks result from an organization’s external environment, which poses a significant threat to the existing business environment. According to Silva and Reddy (2011), 73% of U.S. organizations suffered more than USD 1 billion in sales in the previous five years due to volatile disruptions in the business cycle, with the most recurrent disruption caused by unmanageable natural disasters. Such turmoil often immobilizes supply chains for an extended duration.

A lack of foresight in the organization can also cause disruptions. Disruptions can ripple through the global value chain, which causes vulnerability, uncertainty, and colossal loss of money. For example, during economic hardship, disturbances in the global value chain resulted in excessive costs for many organizations. In an online survey by Vanson Bourne for Interos in 2021, supply chain disruptions cost an average of USD 228 to businesses in the United States. (Interos, 2022.)

Risks in Public Procurement

Public procurement is highly vulnerable to corruption, given the complexity of procurement processes, the high degree of official discretion, and the close interaction between the public and private sectors (OECD, 2016). Interventions to prevent corruption in public procurement have focused on procedural standardization, strengthened transparency, reduced scope for discretion, and digitization in the procurement process.

Governance Risk Assessment System (GRAS)

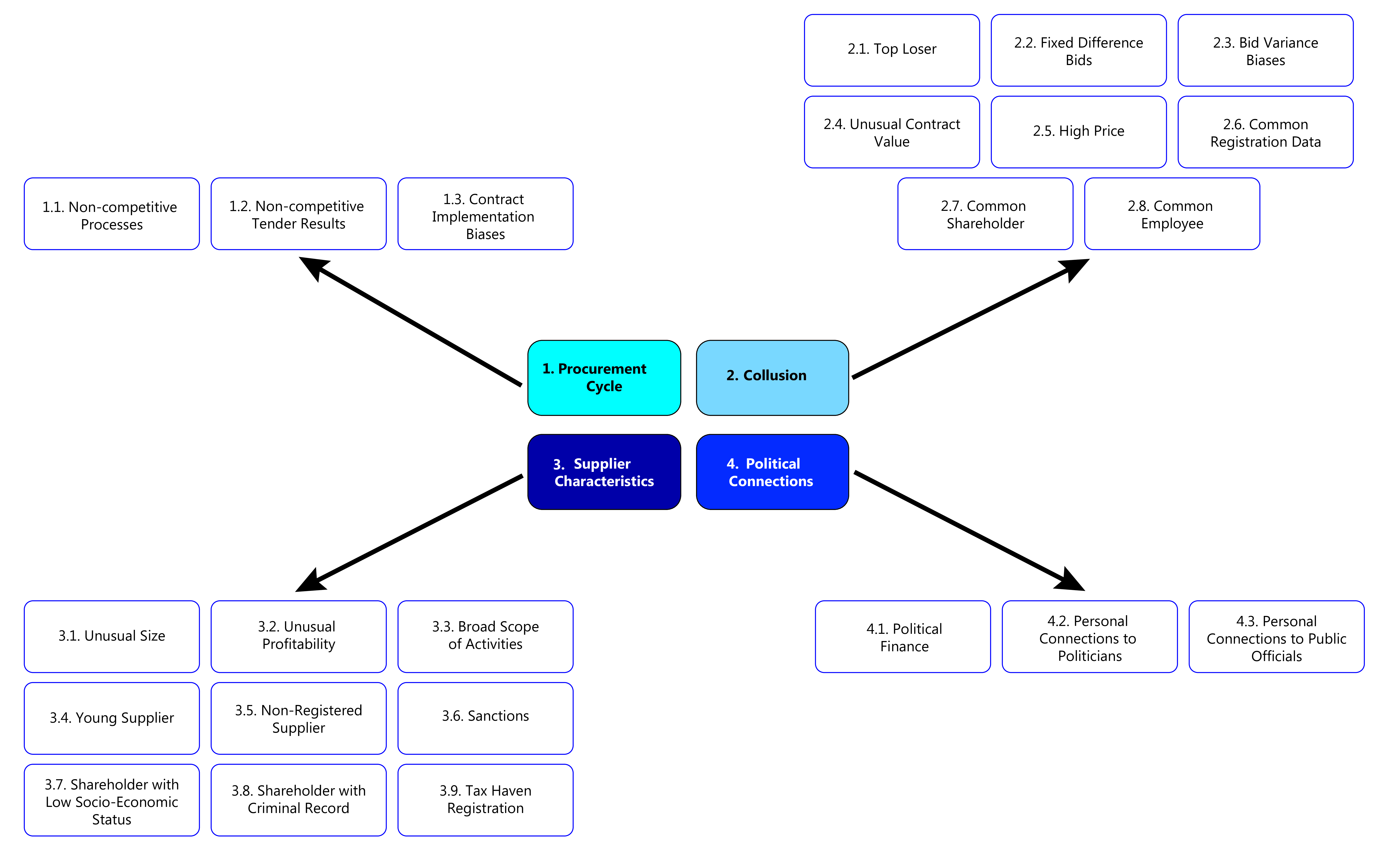

The World Bank developed the Governance Risk Assessment System (GRAS), a tool that uses advanced data analytics to improve the detection of risks of fraud, corruption, and collusion in government contracting. GRAS increases the efficiency and effectiveness of audits and investigations by identifying a wide range of risk patterns.

The GRAS database is set up with a review of four main risk groups:

- Procurement cycle

- Collusion

- Supplier characteristics

- Political connections

Risk Group 1: Procurement Cycle

The risk group for the procurement cycle comprises indicators of corrupt and fraudulent behaviours in public procurement processes. These indicators capture risky behaviours in the three main phases of public procurement: tendering, award, and contract implementation. They indicate deliberate manipulation of public procurement to favour a particular supplier. While these indicators are highly relevant on their own, they are especially useful as they further support and strengthen indicators from risk groups 3 (supplier characteristics) and 4 (political connections)

Among the red flags in the non-competitive processes subgroup, the non-publication of call for tenders is one of the most widely used (Fazekas et al, 2016). This indicator is initially defined for each tender where a call for tender publication is either present (indicator value=1) or absent (indicator value=0). This red flag points at potential corruption because not publishing the call for tenders makes it less likely that eligible bidders notice the bidding opportunity, weakening competition and allowing the contracting body to more easily award the contract to a favoured and/or connected company. This pattern is especially indicative of risks if it happens repeatedly with the same company.

Risk Group 2: Collusion

The collusion risk group comprises indicators that signal collusive behaviour among bidders, such as cartels and bid-rigging practices. GRAS collusion indicators capture collusive outputs, such as coordinated bid prices or persistent losers in tenders, and the means by which companies may coordinate bidding, such as common shareholders or employees across supposedly competing firms. Collusive behaviours involving private actors, i.e. bidders, may take place without the participation of public sector actors (e.g. officials in a buying organization). However, GRAS can identify if corruption and collusion take place together by simultaneously applying collusion and corruption-related red flags.

One of the price-based collusion indicators is Benford’s law. Benford’s law is a statistical rule commonly used in forensic accounting, election monitoring, and the study of economic crime, including collusion and corruption (Berger and Hill, 2015).

Another price-based indicator is relative price, that is, the awarded contract price divided by the initial estimation. The lower the relative price, the greater the savings that could be achieved by competition. Naturally, bid prices—hence contract prices—might be higher than the initial estimations, as budgeting for complex projects is difficult ex-ante. However, repeatedly high relative prices are unusual in an otherwise competitive market: either buyers repeatedly underestimate costs, which is unlikely, or bidders coordinate their bid prices.

Exhibit 10.2 provides an overview of the GRAS groups and the areas of risk covered by these groups.

Risk Group 3: Supplier Characteristics

The risk group of Supplier characteristics comprises indicators for features of government suppliers that indicate likely fraudulent or corrupt behaviour. Suppliers participating in corrupt exchanges act as vehicles of rent extraction and distribution. Just as corrupt government contracting differs from competitive tendering and contract implementation, companies participating in corrupt exchanges are expected to differ from their peers in a number of key features. High-risk supplier characteristics are diverse. Nearly all indicators in this group require combining company and public procurement indicators and data; in some cases, indicators are based on linked datasets such as sanction or debarment lists. Most risk indicators in this group are directly related to specific suppliers, with some related to specific individuals, such as shareholders, and then aggregated at the company level.

One of the most widely used red flags for suppliers is the registration of the supplier or one of its significant shareholders in a secrecy jurisdiction. We identify tax havens using the Financial Secrecy Index of the Tax Justice Network. Awarding a public contract to a company registered in a tax haven presents the risk that anonymous company ownership conceals a conflict of interest of a politically connected owner. Another related risk is the potential loss of tax revenue from the successful supplier through tax evasion or tax avoidance (Fazekas & Kocsis, 2020).

Risk Group 4: Political Connections

The risk group of political connections comprises indicators that capture the relational aspects of corruption, some point directly at conflict of interest while others represent organization-level relationships such as a company donating to a political party. Corruption in public procurement, due to its very nature, involves informal coordination between a range of public, i.e. politicians and bureaucrats, and private actors (Fazekas et al, 2018). Political connections can be demonstrated in a number of ways, such as through political finance, e.g., campaign donations, or personal connections, e.g., family ties.

Risk indicators in this risk group are initially assessed at the level of relations, which are then traced back to specific suppliers, for example, identifying a former politician employed by a government supplier. Among risk indicators surrounding political connections, one of the most widely studied and probably most relevant is the employment of top politicians by companies to gain government favours (Goldman et al., 2013). Former politicians can open doors for a future supplier, share insider information or facilitate bribery in return for contracts. Studies have found that suppliers’ connections to political decision-makers increase their procurement revenue.

Building on the positive results of the GRAS pilot in Brazil, the World Bank seeks to promote implementation of the system in other countries and jurisdictions. Engagement with the government is an essential first step in GRAS implementation. Government agencies, in particular those responsible for anti-corruption, procurement, law enforcement and oversight, as well as public finances, are the obvious clients for a governance risk assessment tool. GRAS relies on public data collected and managed by governments; their buy-in is essential in securing data access and making efforts to improve data disclosure as part of a transparency agenda.

Real Cases in Public Procurement: Learning from Experience

Urban Forestry — Ensuring Value for Money for Tree Maintenance Services

Issue: In a report in April 2019, the Toronto Auditor General found that the City of Toronto failed to manage a contract with an estimated loss of productivity of $2.6 million per year in taxpayers’ money.

Background: The City of Toronto assigns tree maintenance work to city staff members and local contractors. This involves pruning, watering, planting and tree removal. 62% of the sampled contractor logs found discrepancies between the hours claimed, the activity logs and the vehicle’s GPS logs.

Daily logs are meant to provide proof that the service was completed, and the city pays according to the work hours reported on the log. The City’s urban forestry vehicles do not have GPS, so this analysis was only completed on the contractors’ crew.

According to the auditor general’s report, 28 out of the 45 contractor crews sampled did just over 2.5 hours of productive work per day, posing the question, “What happens for the rest of the eight-hour day?” The report stated that the crews spent less time working on trees than documented and took extra breaks throughout the day.

The auditor general proposed 10 recommendations to help Urban Forestry improve its contract management and operational efficiency. The investigation followed in the wake of the death of a senior citizen who was struck and killed by a falling branch.

Outcome: In 2021, the council voted to look at new ways to improve arborist services with a review of internal processes and strengthened contract management. In 2023, a motion was approved to look at insourcing the entire service.

Discussion Questions:

- Should the city stop hiring private companies and handle tasks internally?

- How would vendor management support the compliance of urban forestry?

- What suggestions do you have for this scenario?

Sources: Based on information from https://www.torontoauditor.ca/report/review-of-urban-forestry-ensuring-value-for-money-for-tree-maintenance-services/ and Review of Urban Forestry – Ensuring Value for Money for Tree Maintenance Services (toronto.ca)

Checkpoint 10.2

Image Descriptions

Exhibit 10.1: The image is a structured diagram categorizing various types of risks related to business or supply chain management. It divides risks into three main categories: External Risks, Distribution Channel Risks, and Internal Risks. Each category is presented within a framed box. The External Risks box lists factors such as natural, geopolitical, government, consumer preferences, economic, competitors, cyber attacks, changes in environment, technological, market failures, social, commercial, regulatory climate, ecological, and legislation. The Distribution Channel Risks box includes loss of merchandise, labour unavailability, information accuracy, cargo damage, disasters, infrastructure unavailability, quality of insurance risks, outsourcing risks, partnership risks, and supplier performance risk. The Internal Risks box identifies privacy, security, supply network, forecasting accuracy, reputation, corporate controls, employees, operations and production, legal, non-performance, management and procurement, human error, technical, non-technical, and deficient knowledge. Below these boxes, arrows point towards four business aspects: Value Adding Activities, Supply Chain Stages, Supporting Environment, and End Market, indicating the areas impacted by these risks.

[back]

Exhibit 10.2: The image depicts a framework diagram that outlines potential risk factors in procurement processes. At the center, four main coloured categories are displayed: “Procurement Cycle” in cyan, “Collusion” in light blue, “Supplier Characteristics” in dark blue, and “Political Connections” in navy blue. Arrows extend from each category to subcategories listed around the perimeter. Each subcategory is contained within a white rectangular box with a blue border. The subcategories for “Procurement Cycle” include: “1.1 Non-competitive Processes,” “1.2 Non-competitive Tender Results,” and “1.3 Contract Implementation Biases.” For “Collusion,” subcategories are: “2.1 Top Loser,” “2.2 Fixed Difference Bids,” “2.3 Bid Variance Biases,” “2.4 Unusual Contract Value,” “2.5 High Price,” “2.6 Common Registration Data,” “2.7 Common Shareholder,” and “2.8 Common Employee.” “Supplier Characteristics” subcategories include: “3.1 Unusual Size,” “3.2 Unusual Profitability,” “3.3 Broad Scope of Activities,” “3.4 Young Supplier,” “3.5 Non-Registered Supplier,” “3.6 Sanctions,” “3.7 Shareholder with Low Socio-Economic Status,” “3.8 Shareholder with Criminal Record,” and “3.9 Tax Haven Registration.” Finally, “Political Connections” contains the subcategories: “4.1 Political Finance,” “4.2 Personal Connections to Politicians,” and “4.3 Personal Connections to Public Officials.”

[back]

Attributions

“10.2 Types of Risks and Disruptions” is remixed and adapted from the following:

Supply Chain Risk Management: Literature Review, copyright © 2021 by Amulya Gurtu & Jestin Johny is used under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0, except where otherwise noted.

“Section 7.3: Types of Risks and Disruptions” from Global Value Chain, copyright © 2022 by Dr. Kiranjot Kaur and Iuliia Kau, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Governance Risk Assessment System (GRAS): Advanced Data Analytics for Detecting Fraud, Corruption, and Collusion in Public Expenditures, copyright © 2023 World Bank, licensed under a Deed – Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 IGO – Creative Commons License, except where otherwise noted.

Exhibit 10.1 is adapted from Figure 7.3 in “Section 7.3: Types of Risks and Disruptions” from Global Value Chain, copyright © 2022 by Dr. Kiranjot Kaur and Iuliia Kau, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Exhibit 10.2 is adapted from Figure 1 in Governance Risk Assessment System (GRAS): Advanced Data Analytics for Detecting Fraud, Corruption, and Collusion in Public Expenditures, copyright © 2023 World Bank, licensed under a Deed – Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 IGO – Creative Commons License, except where otherwise noted. This rendition copyright © 2024 Conestoga College, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

The multiple choice questions in the Checkpoint boxes were created using the output from the Arizona State University Question Generator tool and are shared under the Creative Commons – CC0 1.0 Universal License.

Image descriptions and alt text for the exhibits were created using the Arizona State University Image Accessibility Creator and are shared under the Creative Commons – CC0 1.0 Universal License.

An act that involves promising, proposing or giving any undue advantage to a person performing a public function for themselves or any other person, in return for acting or omitting to act in a certain way.

A statistical rule commonly used in forensic accounting, election monitoring, and the study of economic crime, including collusion and corruption.

The awarded contract price divided by the initial estimation.