10.4: Legal and Practical Risks

An Approach to Evaluating Risk

Businesses regularly face a range and variety of risks with gradations of variable severity and frequency. Some risks are minor and easily managed or mitigated while others may entail undesirable conditions and outcomes.

Measuring and evaluating risk is a multi-step process due to the variety of factors that must be considered to accurately assess the potential risks (gains and losses) associated with any given situation. These factors include the likelihood of an event occurring, the potential impact of the event, the ability to mitigate the risks, and the ability to transfer the risks to a third party. Measuring risk involves a thorough analysis of the legal consequences and related elements that contribute to the overall risk profile of a situation. Financial decision-making requires that we evaluate severity levels based on what an individual or a firm can comfortably accept (attitudes toward risk or risk appetite).

Risk and Consequence

Risky actions and activities can lead to a variety of legal consequences. Civil cases involve private disputes between individuals or organizations and are usually resolved by awarding monetary damages, but in some cases, they could involve criminal penalties. A criminal case involves a governmental decision—whether provincial or federal—to prosecute a defendant (a person or organization) for violating society’s laws. The penalties assessed in the case may include imprisonment, financial compensation, loss of license or other sanctions.

In both civil and criminal actions, attorney fees may be expensive, regardless of the outcome of the matter. On the civil side, courts can also impose injunctions (an order to perform or not perform a specific action), and if the financial consequences are severe enough, a firm might risk bankruptcy.

Bankruptcy law governs the rights of creditors and insolvent debtors who cannot pay their debts. In broadest terms, bankruptcy deals with the seizure of the debtor’s assets and their distribution to the debtor’s various creditors. In bankruptcy, the firm might be liquidated or reorganized. This is explored in greater detail in a later section of this resource.

Typical Risk Attitudes

Different people and companies may view the legal risks described above very differently. For instance, some individuals do not mind the prospect of personal bankruptcy and some companies are structured to sustain substantial risk. Others view the prospect of being sued with trepidation. In other words, different people and firms have different attitudes toward the risk-return trade-off.

People are risk averse when they avoid risks, preferring as much security and certainty as reasonably affordable to lower their discomfort level. They may be willing to pay extra to have the security of knowing that unpleasant risks would be removed from their lives. Economists and risk management professionals consider most people to be risk averse.

A risk seeker is a person who hopes to maximize the value of investments by taking higher risks. Much like a gambler, a risk seeker is someone who will accept risk to access greater rewards despite limited probability and unfavourable odds.

A person or entity is said to be risk neutral when risk preference lies between these two extremes. Risk-neutral individuals will not pay extra to have the risk transferred to someone else, nor will they pay to engage in a risky endeavour. Economists consider most widely held or publicly traded corporations as making decisions in a risk-neutral manner since their shareholders can diversify away risk—to take actions that seemingly are not related or have opposite effects or to invest in many possible unrelated products or entities such that the impact of any one event decreases the overall risk.

A Model for Evaluating Legal Risk

This section seeks to provide a simple, non-mathematical model for evaluating legal risk. A “model” is a simplified framework for evaluating a real-life situation. It is not intended to capture all the nuances involved in a particular choice, but it may be useful to decision-makers. The model presented here relies on simple categorization of the likelihood of an event, the consequences of that event, and the decisionmaker’s approach to evaluating risk.

The initial step is to evaluate the likelihood of the event to determine if it is “low” (unlikely), “medium” (somewhat likely), or “high” (very likely). For example, you might think of a low-probability event as one that rarely occurs in a cohort of similar companies, a medium-probability event as one that has occurred several times in the last year for similar companies, and a high-probability event as one that will almost certainly result in litigation.

Next, categorize the severity of the outcome as “slight,” “manageable,” or “severe.” For modeling purposes, a slight outcome is one that would not harm the financial health of the company in a significant way. An example might be a somewhat frivolous lawsuit, which is settled as a “nuisance suit” for a few thousand dollars. A manageable outcome is one that would generate discussion among managers about a possible loss, such as a small business having to potentially pay the medical bills for a customer who is injured in an accident caused by the company’s negligence. This kind of outcome might worry managers but does not risk the future of the business. A severe outcome is one that risks bankruptcy, criminal charges, or other substantial long-term consequences for the firm.

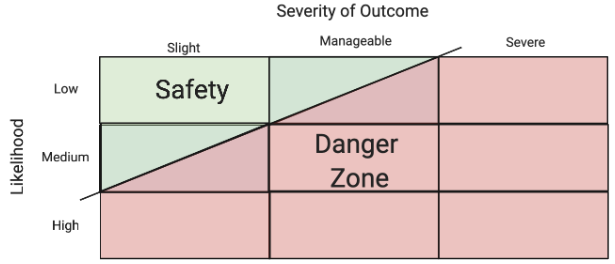

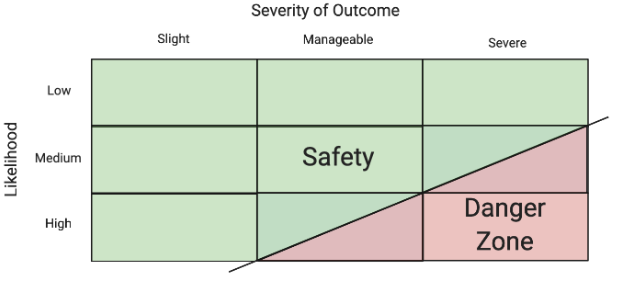

Finally, identify the attitude towards risk. Is the firm risk-averse, risk-neutral, or risk-seeking? In our model, the attitude toward risk forms the shaded “danger zone” in the grid, dividing causes of little from significant concern. The more risk-averse the individual or firm, the farther up and to the left we shift the dividing line, and the more risk-seeking the firm, the farther lower and to the right we shift the line. An extremely risk-averse firm would avoid even low-probability severe events (as shown in Exhibit 10.5(a)), while an extremely risk-seeking firm might avoid only high-probability severe events (as shown in Exhibit 10.5(b)).

Applying this model might look something like the following. We (1) classify the risk tolerance of the firm, (2) then the likelihood of the legal event, and (3) the severity of the consequence. Finally, (4) we analyze how those three interact and offer a conclusion: Is this a high-risk decision in the legal danger zone or a low-risk decision in the zone of safety?

Suppose a ride-sharing firm was considering whether to expand to a city that has somewhat hostile regulations for ridesharing. However, the consequences for entering the market and losing a legal challenge are simply to withdraw or pay an insubstantial fine. Let’s apply the model:

- We might thus classify this firm as risk-seeking based on its past attitude towards the law and the potential rewards at stake.

- As the new market appears hostile, the likelihood of legal challenge is assessed to be medium or high.

- Relative to the size of the firm, a modest fine is a small consequence. We might then classify the severity of the outcome as low.

- Although the likelihood of legal action is medium to high, the potential consequence is slight.

- This decision is likely a low-risk legal decision within the legal safety zone for the firm. They might also be classified as risk-neutral because the company finds it advantageous to engage in legally risky behaviour.

Organizations seek to reduce the legal risks they have identified and assessed. Reducing legal risk exposure may be referred to as risk mitigation. It is worthwhile to highlight some potential methods to mitigate legal risk which may be overlooked or undervalued. These methods include the following:

Insurance

Both individuals and businesses have significant needs for various types of insurance to provide protection for health care, for their property, and for legal claims made against them by others. Insurance allows individuals to pay a certain amount today to avoid uncertain losses in the future.

Businesses face a host of risks that could result in substantial liabilities. Many types of policies are available, including policies for owners, landlords, and tenants (covering liability incurred on the premises); for manufacturers and contractors (for liability incurred on all premises); for a company’s products and completed operations (for liability that results from warranties on products or injuries caused by products); for owners and contractors (protective liability for damages caused by independent contractors engaged by the insured); and for contractual liability (for failure to abide by performances required by specific contracts). Depending on the business context, insurance may be required by law, or it may be a viable risk management application that businesses should consider and review regularly.

Regulatory Review

Many firms find it worthwhile to preemptively hire an attorney to review a product for regulatory and litigation risk before launching it. For a fee, a specialized attorney can examine the product and provide a report on potential regulatory violations and lawsuit risks. Many firms might be surprised at the substantially increased risk of litigation based on innocuous statements on packaging, for instance.

Limitation and Exclusion Clauses

The use of liability waivers, exclusion clauses, hardship clauses (force majeure), warning labels, caution signs, safety rails, and related activities can help prevent litigation. Liability waivers may reduce litigation risk by requiring that individuals specifically agree they will not sue in case of injury during an activity as long as such limitation and exclusion clauses are not contrary to public policy or are unconscionable. Physical safeguards against injury can help reduce the probability of potential negligence lawsuits by preventing injury in the first place. Businesses that practice prudent preemptive tort defence can lower their legal risks substantially.

Knowing the Law

Another way to reduce legal risk is to be familiar with the law. An attorney will not always be around to consult, or it may be cost-prohibitive to use their services at times. The law is vast and complicated, but many legal concepts foundational to business are easy to understand.

The more one knows about the law, the easier it is to avoid compromising legal situations, be conversant with those who can offer legal counsel, and make decisions that balance legal and ethical interests with other strategic concerns.

Approaching law from a risk management approach is crucial to evaluate the legal environment of business.

Evaluating legal risk requires understanding the likelihood of legal action, the severity of the consequences, and the risk tolerance level of the company. Even low-probability legal events can be so severe that risk-averse firms may take action to avoid them, while even high-probability legal events may not bother risk-seeking firms.

Preemptively avoiding tort liability (employing smart contracting principles) and enacting safety messaging and protocols can help to avoid business risks. Insurance against legal claims can also reduce uncertainty at a price.

Public Procurement Playbook

Watch this video to learn more about contracts and issues in the procurement process.

Source: Skill Dynamics. (2012, March 5). Legal Course: Contracts and Issues in Procurement. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p1kHJ0Pj6M0

Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Processes for Mitigating Risk

Negotiation

We frequently engage in negotiations as we go about our daily activities, often without being consciously aware that we are doing so. Negotiation can be simple, e.g., two friends deciding on a place to eat dinner, or complex, e.g., governments of several nations trying to establish import and export quotas across multiple industries. When a formal proceeding is started in the court system, alternative dispute resolution (ADR), or ways of solving an issue with the intent to avoid litigation, may be employed. Negotiation is often the first step used in ADR. While there are other forms of alternative dispute resolution, negotiation is considered the simplest because it does not require outside parties. A Government of Canada webpage defines ‘negotiation” as: “…a discussion between at least two parties that leads to an outcome of a certain issue.”[1]

This is an uncomplicated definition that captures a fundamental feature of negotiation — it is undertaken with the intention of leading to an outcome. There are several ways of thinking about negotiation, including how many parties are involved. For example, if two small business owners find themselves in a disagreement over property lines, they will frequently engage in dyadic negotiation. Put simply, dyadic negotiation involves two individuals interacting with one another to resolve a dispute. If a third neighbour overhears the dispute and believes one or both of them are wrong about the property line, then group negotiation could ensue. Group negotiation involves more than two individuals or parties, and by its very nature, it is often more complex, time-consuming, and challenging to resolve.

While dyadic and group negotiations may involve different dynamics, one of the most important aspects of any negotiation, regardless of the number of negotiators, is the objective. Negotiation experts recognize two major goals of negotiation: relational and outcome. Relational goals are focused on building, maintaining, or repairing a partnership, connection, or rapport with another party. Outcome goals, on the other hand, concentrate on achieving certain end results. The goal of any negotiation is influenced by numerous factors, such as whether there will be contact with the other party in the future. For example, when a business negotiates with a supply company that it intends to do business with soon, it will try to focus on “win-win” solutions that provide the most value for each party. In contrast, if an interaction is of a one-time nature, that same company might approach a supplier with a “win-lose” mentality, viewing its objective as maximizing its own value at the expense of the other party’s value. This approach is referred to as zero-sum negotiation and is considered a “hard” negotiating style. Zero-sum negotiation is based on the notion that there is a “fixed pie,” and the larger the slice that one party receives, the smaller the slice the other party will receive. Win-win approaches to negotiation are sometimes referred to as integrative, while win-lose approaches are called distributive.

Negotiation Style

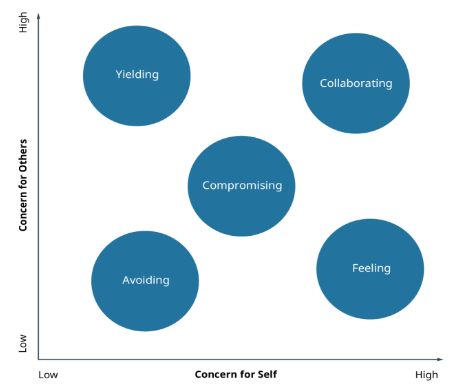

Everyone has a different way of approaching negotiation, depending on the circumstance and the person’s personality. However, the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) is a questionnaire that provides a systematic framework for categorizing five broad negotiation styles. It is closely associated with work done by conflict resolution experts Dean Pruitt and Jeffrey Rubin. These styles are often considered in terms of the level of self-interest instead of how other negotiators feel. These five general negotiation styles include:

Forcing

If a party has high concern for itself and low concern for the other party, it may adopt a competitive approach that only takes into account the outcomes it desires. This negotiation style is most prone to zero-sum thinking. For example, a car dealership that tries to give each customer as little as possible for his or her trade-in vehicle would be applying a forcing negotiation approach. While the party using the forcing approach is only considering its own self-interests, this negotiating style often undermines the party’s long-term success. For example, in the car dealership example, if customers feel they have not received a fair trade-in value after the sale, they may leave negative reviews, will not refer their friends and family to that dealership and will not return to it when the time comes to buy another car.

Collaborating

If a party has high concern and care for itself and the other party, it will often employ a collaborative negotiation style that seeks maximum gain for both. In this negotiating style, parties recognize that acting in their mutual interests may create greater value and synergies.

Compromising

A compromising negotiation approach will occur when parties share concerns for themselves and the other party. While it is not always possible to collaborate, parties can often find certain points that are more important to one than the other and, in that way, find ways to isolate what is most important to each party.

Avoiding

When a party has low concern for itself and the other party, it will often try to avoid negotiation completely.

Yielding

Finally, when a party has low self-concern and high concern for the other party, it will yield to demands that may not be in its best interest. As with avoidance techniques, it is important to ask why the party has low self-concern. It may be due to an unfair power differential between the two parties that has caused the weaker party to feel it is futile to represent its own interests.

Exhibit 10.6 illustrates why negotiation is often fraught with ethical issues.

Limitations to Negotiation

In a negotiation, there is no neutral third party to ensure that rules are followed, that the negotiation strategy is fair (the parties involved may have unequal bargaining power), or that the overall outcome is sound. Moreover, any party can walk away whenever it wishes. There is no guarantee of realizing an intended outcome.

Mediation

Mediation is a method of dispute resolution that relies on an impartial third-party decision-maker, known as a mediator, to settle a dispute. While requirements vary by location or jurisdiction, a mediator is someone who has been trained in conflict resolution, though they may not have any expertise in the subject matter that is being disputed. Mediation is a form of dispute resolution. It is often undertaken because it can help disagreeing parties avoid the time-consuming and expensive procedures involved in court litigation. Courts will often recommend that a plaintiff, or the party initiating a lawsuit, and a defendant, or the party that is accused of wrongdoing, attempt mediation before proceeding to trial. This recommendation is especially true for issues that are filed in small claims courts, where judges attempt to streamline dispute resolution.

For businesses, the savings associated with mediation can be substantial. Mediation is distinguished by its focus on solutions. Instead of focusing on discoveries, testimonies, and expert witnesses to assess what has happened in the past, it is future-oriented. Mediators focus on generating approaches to disputes that overcome obstacles to settlement.

Benefits of Mediation

Successful mediators work to immediately establish a personal rapport with the disputing parties. They often have a short time to interact with the parties and work to position themselves as trustworthy facilitators. The mediator’s conflict resolution skills are critical in guiding the parties toward reaching a resolution. Benefits of mediation include:

Confidentiality

Since court proceedings become a matter of public record, it can be advantageous to use mediation to preserve anonymity. This aspect can be especially important when dealing with sensitive matters, where one or both parties feel it is best to keep the situation private. Discussions during a mediation are not admissible as evidence if the parties proceed to litigation.

Creativity

Mediators are trained to find ways to resolve disputes and may apply outside-the-box thinking to suggest a resolution that the parties had not considered. Since disagreeing parties can be feeling emotionally contentious toward one another, they may not be able to consider other solutions. In addition, a skilled mediator may be able to recognize cultural differences between the parties that are influencing the parties’ ability to reach a compromise, and thus leverage this awareness to create a novel solution.

Control

When a case goes to trial, both parties give up a certain degree of control over the outcome. A judge may come up with a solution to which neither party is in favour. In contrast, mediation gives the disputing parties opportunities to find common ground on their own terms before relinquishing control to outside forces. Parties often enter into a legally binding contract that embodies the terms of the resolution immediately after a successful mediation. Therefore, the terms of the mediation can become binding if they are reduced to a contract.

Arbritation

According to the Government of Canada “Dispute Resolution Reference Guide:” “Arbitration is perhaps the most widely known dispute resolution process. Like litigation, arbitration utilizes an adversarial approach that requires a neutral party to render a decision.” (https://justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/csj-sjc/dprs-sprd/res/drrg-mrrc/06.html).

Arbitration is overseen by a neutral arbitrator or an individual who is responsible for deciding on how to resolve a dispute and who can decide on an award or a course of action that the arbiter believes is fair, given the situation. An award can be a monetary payment that one party must pay to the other; however, awards need not always be financial in nature. An award may require that one business stop engaging in a certain practice that is deemed unfair to the other business. As distinguished from mediation, in which the mediator simply serves as a facilitator who is attempting to help the disagreeing parties reach an agreement, an arbitrator acts more like a judge in a court trial and often has legal expertise, although they may or may not have subject matter expertise. Many arbitrators are current or retired lawyers and judges.

Types of Arbitration Agreements

Parties can enter into either voluntary or involuntary arbitration. In voluntary arbitration, the disputing parties have decided, of their own accord, to seek arbitration as a way to potentially settle their dispute. Depending on provincial laws (each province and territory in Canada has its own separate arbitration legislation) and the nature of the dispute, disagreeing parties may have to attempt arbitration before resorting to litigation; this requirement is known as involuntary arbitration because it is forced upon them by an outside party.

Arbitration can be either binding or non-binding. In binding arbitration, the decision of the arbitrator(s) is final, and except in rare circumstances, neither party can appeal the decision through the court system. In non-binding arbitration, the arbitrator’s award can be considered a recommendation; it is only finalized if both parties agree that it is an acceptable solution. Having a neutral party assess the situation may help disputants to rethink and reassess their positions and reach a future compromise.

Issues Covered by Arbitration Agreements

There are many instances in which arbitration agreements may prove helpful as a form of alternative dispute resolution. While arbitration can be useful for resolving family law matters, such as divorce, custody, and child support issues, in the domain of business law, it has three major applications:

Labour

Arbitration has often been used to resolve labour disputes through interest arbitration and grievance arbitration. Interest arbitration addresses disagreements about the terms to be included in a new contract, e.g., workers of a union want their break time increased from 15 to 25 minutes. In contrast, grievance arbitration covers disputes about the implementation of existing agreements. In the example previously given, if the workers felt they were being forced to work through their 15-minute break, they might engage in this type of arbitration to resolve the matter.

Business Transactions

Whenever two parties conduct business transactions, there is potential for misunderstandings and mistakes. Both business-to-business transactions and business-to-consumer transactions can potentially be solved through arbitration. Any individual or business who is unhappy with a business transaction can attempt arbitration.

Property Disputes

Businesses can have various types of property disputes. These might include disagreements over physical property, e.g., deciding where one property ends and another begins, or intellectual property, e.g., trade secrets, inventions, and artistic works.

Civil Disputes

Typically, civil disputes, as opposed to criminal matters, attempt to use arbitration as a means of dispute resolution. While definitions can vary across jurisdictions, a civil matter is generally one that is brought when one party has a grievance against another party and seeks monetary damages. In contrast, in a criminal matter, a government pursues an individual or group for violating laws meant to establish the best interests of the public.

Ethics of Commercial Arbitration Clauses

Going to court to solve a dispute is a costly endeavour, and for large companies, it is possible to incur millions of dollars in legal expenses. While arbitration is meant to be a form of dispute resolution that helps disagreeing parties find a low-cost, time-efficient solution, it has become increasingly important to question whose expenses are being lowered, and to what effect. Many consumer advocates are fighting against what are known as forced-arbitration clauses, in which consumers agree to settle all disputes through arbitration, effectively waiving their right to sue a company in court. Some of these forced arbitration clauses cause the other party to forfeit their right to appeal an arbitration decision or participate in any kind of class action lawsuit, in which individuals who have a similar issue sue as one collective group.

Arbitration Procedures

When parties enter into arbitration, certain procedures are followed, although not all arbitration agreements have the same procedures. It depends on the types of agreements made in advance by the disputing parties. Typically, the initial step identifies the number of arbitrators needed, along with how they will be chosen. Parties that enter into willing arbitration may have more control over this decision, while those that do so unwillingly may have a limited pool of arbitrators from which to choose. In the case of willing arbitration, parties may decide to have three arbitrators, one chosen by each of the disputants and the third chosen by the elected arbitrators. Next, a timeline is established, and evidence is presented by both parties. Since arbitration is less formal than court proceedings, the evidence phase typically goes faster than it would in a courtroom setting. Finally, the arbitrator will decide and inform the parties in writing of the award.

Judicial Enforcement of Arbitration Awards

While it might seem that the party that is awarded a settlement by an arbitrator has reason to be relieved that the matter is resolved, sometimes this decision represents just one more step toward actually receiving the award. While a party may honour the award and voluntarily comply, this outcome is not always the case. In cases where the other party does not comply, the next step is to petition the court to enforce the arbitrator’s decision. This task can be accomplished by numerous mechanisms, depending on the governing laws.

Checkpoint 10.4

Image Descriptions

Exhibit 10.5(a): The image is a risk assessment matrix divided into a grid with three columns and three rows. The horizontal axis is labeled “Severity of Outcome” with categories “Slight,” “Manageable,” and “Severe.” The vertical axis is labeled “Likelihood” with levels “Low,” “Medium,” and “High.” The matrix features two distinct zones: a green “Safety” zone and a red “Danger Zone.” The “Safety” zone appears in the top left, covering low likelihood with slight and manageable outcomes and extending partially into medium likelihood with slight outcomes. The “Danger Zone” covers all high likelihood risks and extends into medium likelihood with manageable and severe outcomes, as well as low likelihood with severe outcomes. A diagonal line separates these two zones, highlighting the transition from acceptable to urgent risks. The matrix indicates a tendency toward a risk-averse firm that avoids most risks.

[back]

Exhibit 10.5(b): The image is a risk assessment matrix with a two-dimensional grid. The horizontal axis is labeled “Severity of Outcome” with three categories: Slight, Manageable, and Severe. The vertical axis is labeled “Likelihood” and is divided into Low, Medium, and High categories. The matrix is predominantly shaded green, representing the Safety Zone, covering most of the left side and extending slightly towards the right. It includes areas with risks of low to medium likelihood and slight to manageable severity. The bottom right section is shaded pink, denoting the Danger Zone, which includes risks that are highly likely and have high severity. A diagonal line separates the green Safety Zone from the pink Danger Zone, extending from the top of the Severe severity of outcome column through the manageable column and ending at the high likelihood square. The alignment suggests an emphasis on avoiding only those risks that have the possibility of severe outcomes.

[back]

Exhibit 10.6: The image is a diagram depicting the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Model Instrument (TKI) model. It features a coordinate plane with two axes: “Concern for Self” on the horizontal axis and “Concern for Others” on the vertical axis. Both axes range from “Low” to “High.” There are five blue circles placed strategically within the plane to represent different conflict-handling styles. Starting from the top-left corner and moving clockwise, the circles are labeled: “Yielding,” “Collaborating,” “Forcing,” “Avoiding,” and “Compromising.”

[back]

Attributions

“10.4 Legal and Practical Risks” is adapted from “Chapter 2: Legal Risk Management” from Business Law and Ethics Canadian Edition, copyright © 2023 by Craig Ervine, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Exhibits 10.5(a) and 10.5 (b) are taken from “Chapter 2: Legal Risk Management” from Business Law and Ethics Canadian Edition, copyright © 2023 by Craig Ervine, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Exhibit 10.6 is taken from Figure 2.3 in “Chapter 2: Legal Risk Management” from Business Law and Ethics Canadian Edition, copyright © 2023 by Craig Ervine, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The multiple choice questions in the Checkpoint boxes were created using the output from the Arizona State University Question Generator tool and are shared under the Creative Commons – CC0 1.0 Universal License.

Image descriptions and alt text for the exhibits were created using the Arizona State University Image Accessibility Creator and are shared under the Creative Commons – CC0 1.0 Universal License.

- Government of Canada. (n.d.). Win-win negotiations. Canada.ca. Retrieved November 20, 2024, from https://www.canada.ca/en/heritage-information-network/services/intellectual-property-copyright/guide-developing-digital-licensing-agreement-strategy/win-win-negotiations.html ↵

Someone who avoid risks, preferring as much security and certainty as reasonably affordable to lower their discomfort level.

Someone who will accept risk to access greater rewards despite limited probability and unfavourable odds.

Someone who will not pay extra to have the risk transferred to someone else, nor will they pay to engage in a risky endeavour.

Employing smart contracting principles and protocols that help to avoid business risks.

To be held accountable for wrong actions (other than under contract.)

Two individuals interacting with one another to resolve a dispute.

Involves more than two individuals or parties to resolve a dispute.

Goals focused on building, maintaining, or repairing a partnership, connection, or rapport with another party.

Concentrate on achieving certain end results. The goal of any negotiation is influenced by numerous factors.

The tendency to view a negotiation as purely distributive; what one side wins, the other side loses.

The submission of a dispute to a neutral party who hears the case and makes a decision. Arbitration takes the place of a trial before a judge or jury.

That which is commonly employed in simple conflicts where both parties only need guidance.

Interest arbitration is a type of arbitration that is used to resolve collective bargaining disputes.

A final and binding process to resolve disputes about the interpretation of an agreement during the life of that agreement.