153

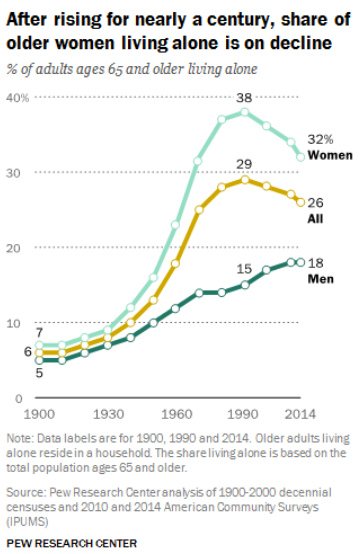

Do those in late adulthood primarily live alone? No. In 2014, of those 65 years of age and older, approximately 72% of men and 46% of women lived with their spouse (Vespa & Schondelmyer, 2015). Between 1900 and 1990 the number of older adults living alone increased, most likely due to improvements in health and longevity during this time (see Figure 9.35). Since 1990 the number of older adults living alone has declined, because of older women more likely to be living with their spouse or children (Stepler, 2016c).

Women continue to make up the majority of older adults living alone, although that number has dropped from those living alone in 1990 (Stepler, 2016a). Older women are more likely to be unmarried, living with children, with other relatives or non-relatives. Older men are more likely to be living alone than they were in 1990, although older men are more likely to reside with their spouse. The rise in divorce among those in late adulthood, along with the drop-in remarriage rate, has resulted in slightly more older men living alone today than in the past (Stepler, 2016c).

Older adults who live alone report feeling more financially strapped than do those living with others (Stepler, 2016d). According to a Pew Research Center Survey, only 33% of those living alone reported they were living comfortably, while nearly 49% of those living with others said they were living comfortably. Similarly, 12% of those living alone, but only 5% of those living with others, reported that they lacked money for basic needs (Stepler, 2016d).

Do those in late adulthood primarily live with family members? No. There are significantly fewer older adults living in multigenerational housing; that is three generations living together, than in previous generations (Erber & Szuchman, 2015). According to the Pew Research Center (2011), nearly 17% of the population lived in a house with at least two adult generations based on the 2010 census results. However, ethnic differences are noted in the percentage of multigenerational households with Hispanic (22%), Black (23%), and Asian (25%) families living together in greater numbers than White families (13%). Consequently, with the exception of some cultural groups, the majority of older adults wish to live independently for as long as they are able.

Do those in late adulthood move after retirement? No. According to Erber and Szuchman (2015), the majority of those in late adulthood remain in the same location, and often in the same house, where they lived before retiring. Although some younger late adults (65-74 years) may relocate to warmer climates, once they are older (75-84 years) they often return to their home states to be closer to adult children (Stoller & Longino, 2001). Despite the previous trends, however, the recent housing crisis has kept those in late adulthood in their current suburban locations because they are unable to sell their homes (Erber & Szuchman, 2015).

Do those in late adulthood primarily live in institutions? No. Only a small portion (3.2%) of adults older than 65 lived in an institution in 2015 (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). However, as individuals increase in age the percentage of those living in institutions, such as a nursing home, also increases. Specifically: 1% of those 65-74, 3% of those 75-84, and 10% of those 85 years and older lived in an institution in 2015. Due to the increasing number of baby boomers reaching late adulthood, the number of people who will depend on long-term care is expected to rise from 12 million in 2010 to 27 million in 2050 (United States Senate Commission on Long-Term Care, 2013). To meet this higher demand for services, a focus on the least restrictive care alternatives has resulted in a shift toward home and community-based care instead of placement in a nursing home (Gatz et al., 2016).

The Dependence-Support and Independence-Ignore Script

Dependency and the loss of independence is a central concern for many people in late adulthood. Caretakers with the best of intentions may create a dynamic that encourages ever-increasing levels of dependence. This happens through behaviour patterns (scripts) that subtly and not so subtly encourage dependency and squash independence through reinforcement.

Reinforcement is one of the foundational principles of learning theory. Central to reinforcement is the reinforcer. A reinforcer is something that increases the likelihood that a behaviour will reoccur. Within learning theory, it is well established that behaviours that are reinforced will increase in frequency and that those which are ignored or punished diminish.

The notion of reinforcement has particular relevance to familial and institutional (be it hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, or rehabilitation centres) social dynamics. The dependence-support and independence-ignore script reminds us that caretakers, be them family members or medical staff, may fall into a pattern behaviour (a script) which fosters dependency in senior citizens on the one hand extinguishes independence on the other.

Senior citizens’ independence is very important to their quality of life. In this dynamic, dependent behaviours on the part of the elderly person are attended to immediately (reinforced) while independent behaviours are at best ignored. The danger here is the creation and maintenance of a feedback loop of ever-increasing dependency, and the concurrent extinction of independent behaviours. Recognizing and changing these scripts so as to encourage and reinforce independent behaviours as much as possible has been shown to be a useful corrective – one which allows lives to be lived with dignity and with as much independence as possible.

Link to Learning

Baltes and Wahl (2009) wrote an excellent study on the dependence-support and independence-ignore script, which provides quite a lot more detail on this interesting subject. Be sure to read the study abstract, and consider acquiring the paper if you’d like to learn more.

In recent years, there has been a shift in gerontology from a focus on decline and remediation to a focus on the components of successful aging. This multi-level approach looks at a range of aspects from physical health, to mental acuity, to social relationships, productivity, and overall life satisfaction.