6 Evolutionary Theories in Psychology

Original chapter by David M. Buss adapted by the Queen’s Psychology Department

This Open Access chapter was originally written for the NOBA project. Information on the NOBA project can be found below.

Evolution or change over time occurs through the processes of natural and sexual selection. In response to problems in our environment, we adapt both physically and psychologically to ensure our survival and reproduction. Sexual selection theory describes how evolution has shaped us to provide a mating advantage rather than just a survival advantage and occurs through two distinct pathways: intrasexual competition and intersexual selection. Gene selection theory, the modern explanation behind evolutionary biology, occurs through the desire for gene replication. Evolutionary psychology connects evolutionary principles with modern psychology and focuses primarily on psychological adaptations: changes in the way we think in order to improve our survival. Two major evolutionary psychological theories are described: Sexual strategies theory describes the psychology of human mating strategies and the ways in which women and men differ in those strategies. Error management theory describes the evolution of biases in the way we think about everything.

Learning Objectives

- Learn what “evolution” means.

- Define the primary mechanisms by which evolution takes place.

- Identify the two major classes of adaptations.

- Define sexual selection and its two primary processes.

- Define gene selection theory.

- Understand psychological adaptations.

- Identify the core premises of sexual strategies theory.

- Identify the core premises of error management theory, and provide two empirical examples of adaptive cognitive biases.

Introduction

If you have ever been on a first date, you’re probably familiar with the anxiety of trying to figure out what clothes to wear or what perfume or cologne to put on. In fact, you may even consider flossing your teeth for the first time all year. When considering why you put in all this work, you probably recognize that you’re doing it to impress the other person. But how did you learn these particular behaviors? Where did you get the idea that a first date should be at a nice restaurant or someplace unique? It is possible that we have been taught these behaviors by observing others. It is also possible, however, that these behaviors—the fancy clothes, the expensive restaurant—are biologically programmed into us. That is, just as peacocks display their feathers to show how attractive they are, or some lizards do push-ups to show how strong they are, when we style our hair or bring a gift to a date, we’re trying to communicate to the other person: “Hey, I’m a good mate! Choose me! Choose me!”

However, we all know that our ancestors hundreds of thousands of years ago weren’t driving sports cars or wearing designer clothes to attract mates. So how could someone ever say that such behaviors are “biologically programmed” into us? Well, even though our ancestors might not have been doing these specific actions, these behaviors are the result of the same driving force: the powerful influence of evolution. Yes, evolution—certain traits and behaviors developing over time because they are advantageous to our survival. In the case of dating, doing something like offering a gift might represent more than a nice gesture. Just as chimpanzees will give food to mates to show they can provide for them, when you offer gifts to your dates, you are communicating that you have the money or “resources” to help take care of them. And even though the person receiving the gift may not realize it, the same evolutionary forces are influencing his or her behavior as well. The receiver of the gift evaluates not only the gift but also the gift-giver’s clothes, physical appearance, and many other qualities, to determine whether the individual is a suitable mate. But because these evolutionary processes are hardwired into us, it is easy to overlook their influence.

To broaden your understanding of evolutionary processes, this module will present some of the most important elements of evolution as they impact psychology. Evolutionary theory helps us piece together the story of how we humans have prospered. It also helps to explain why we behave as we do on a daily basis in our modern world: why we bring gifts on dates, why we get jealous, why we crave our favorite foods, why we protect our children, and so on. Evolution may seem like a historical concept that applies only to our ancient ancestors but, in truth, it is still very much a part of our modern daily lives.

Basics of Evolutionary Theory

Evolution simply means change over time. Many think of evolution as the development of traits and behaviors that allow us to survive this “dog-eat-dog” world, like strong leg muscles to run fast, or fists to punch and defend ourselves. However, physical survival is only important if it eventually contributes to successful reproduction. That is, even if you live to be a 100-year-old, if you fail to mate and produce children, your genes will die with your body. Thus, reproductive success, not survival success, is the engine of evolution by natural selection. Every mating success by one person means the loss of a mating opportunity for another. Yet every living human being is an evolutionary success story. Each of us is descended from a long and unbroken line of ancestors who triumphed over others in the struggle to survive (at least long enough to mate) and reproduce. However, in order for our genes to endure over time—to survive harsh climates, to defeat predators—we have inherited adaptive, psychological processes designed to ensure success.

At the broadest level, we can think of organisms, including humans, as having two large classes of adaptations—or traits and behaviors that evolved over time to increase our reproductive success. The first class of adaptations are called survival adaptations: mechanisms that helped our ancestors handle the “hostile forces of nature.” For example, in order to survive very hot temperatures, we developed sweat glands to cool ourselves. In order to survive very cold temperatures, we developed shivering mechanisms (the speedy contraction and expansion of muscles to produce warmth). Other examples of survival adaptations include developing a craving for fats and sugars, encouraging us to seek out particular foods rich in fats and sugars that keep us going longer during food shortages. Some threats, such as snakes, spiders, darkness, heights, and strangers, often produce fear in us, which encourages us to avoid them and thereby stay safe. These are also examples of survival adaptations. However, all of these adaptations are for physical survival, whereas the second class of adaptations are for reproduction, and help us compete for mates. These adaptations are described in an evolutionary theory proposed by Charles Darwin, called sexual selection theory.

Sexual Selection Theory

Darwin noticed that there were many traits and behaviors of organisms that could not be explained by “survival selection.” For example, the brilliant plumage of peacocks should actually lower their rates of survival. That is, the peacocks’ feathers act like a neon sign to predators, advertising “Easy, delicious dinner here!” But if these bright feathers only lower peacocks’ chances at survival, why do they have them? The same can be asked of similar characteristics of other animals, such as the large antlers of male stags or the wattles of roosters, which also seem to be unfavorable to survival. Again, if these traits only make the animals less likely to survive, why did they develop in the first place? And how have these animals continued to survive with these traits over thousands and thousands of years? Darwin’s answer to this conundrum was the theory of sexual selection: the evolution of characteristics, not because of survival advantage, but because of mating advantage.

Sexual selection occurs through two processes. The first, intrasexual competition, occurs when members of one sex compete against each other, and the winner gets to mate with a member of the opposite sex. Male stags, for example, battle with their antlers, and the winner (often the stronger one with larger antlers) gains mating access to the female. That is, even though large antlers make it harder for the stags to run through the forest and evade predators (which lowers their survival success), they provide the stags with a better chance of attracting a mate (which increases their reproductive success). Similarly, human males sometimes also compete against each other in physical contests: boxing, wrestling, karate, or group-on-group sports, such as football. Even though engaging in these activities poses a “threat” to their survival success, as with the stag, the victors are often more attractive to potential mates, increasing their reproductive success. Thus, whatever qualities lead to success in intrasexual competition are then passed on with greater frequency due to their association with greater mating success.

The second process of sexual selection is preferential mate choice, also called intersexual selection. In this process, if members of one sex are attracted to certain qualities in mates—such as brilliant plumage, signs of good health, or even intelligence—those desired qualities get passed on in greater numbers, simply because their possessors mate more often. For example, the colorful plumage of peacocks exists due to a long evolutionary history of peahens’ (the term for female peacocks) attraction to males with brilliantly colored feathers.

In all sexually-reproducing species, adaptations in both sexes (males and females) exist due to survival selection and sexual selection. However, unlike other animals where one sex has dominant control over mate choice, humans have “mutual mate choice.” That is, both women and men typically have a say in choosing their mates. And both mates value qualities such as kindness, intelligence, and dependability that are beneficial to long-term relationships—qualities that make good partners and good parents.

Gene Selection Theory

In modern evolutionary theory, all evolutionary processes boil down to an organism’s genes. Genes are the basic “units of heredity,” or the information that is passed along in DNA that tells the cells and molecules how to “build” the organism and how that organism should behave. Genes that are better able to encourage the organism to reproduce, and thus replicate themselves in the organism’s offspring, have an advantage over competing genes that are less able. For example, take female sloths: In order to attract a mate, they will scream as loudly as they can, to let potential mates know where they are in the thick jungle. Now, consider two types of genes in female sloths: one gene that allows them to scream extremely loudly, and another that only allows them to scream moderately loudly. In this case, the sloth with the gene that allows her to shout louder will attract more mates—increasing reproductive success—which ensures that her genes are more readily passed on than those of the quieter sloth.

Essentially, genes can boost their own replicative success in two basic ways. First, they can influence the odds for survival and reproduction of the organism they are in (individual reproductive success or fitness—as in the example with the sloths). Second, genes can also influence the organism to help other organisms who also likely contain those genes—known as “genetic relatives”—to survive and reproduce (which is called inclusive fitness). For example, why do human parents tend to help their own kids with the financial burdens of a college education and not the kids next door? Well, having a college education increases one’s attractiveness to other mates, which increases one’s likelihood for reproducing and passing on genes. And because parents’ genes are in their own children (and not the neighborhood children), funding their children’s educations increases the likelihood that the parents’ genes will be passed on.

Understanding gene replication is the key to understanding modern evolutionary theory. It also fits well with many evolutionary psychological theories. However, for the time being, we’ll ignore genes and focus primarily on actual adaptations that evolved because they helped our ancestors survive and/or reproduce.

Evolutionary Psychology

Evolutionary psychology aims the lens of modern evolutionary theory on the workings of the human mind. It focuses primarily on psychological adaptations: mechanisms of the mind that have evolved to solve specific problems of survival or reproduction. These kinds of adaptations are in contrast to physiological adaptations, which are adaptations that occur in the body as a consequence of one’s environment. One example of a physiological adaptation is how our skin makes calluses. First, there is an “input,” such as repeated friction to the skin on the bottom of our feet from walking. Second, there is a “procedure,” in which the skin grows new skin cells at the afflicted area. Third, an actual callus forms as an “output” to protect the underlying tissue—the final outcome of the physiological adaptation (i.e., tougher skin to protect repeatedly scraped areas). On the other hand, a psychological adaptation is a development or change of a mechanism in the mind. For example, take sexual jealousy. First, there is an “input,” such as a romantic partner flirting with a rival. Second, there is a “procedure,” in which the person evaluates the threat the rival poses to the romantic relationship. Third, there is a behavioral output, which might range from vigilance (e.g., snooping through a partner’s email) to violence (e.g., threatening the rival).

Evolutionary psychology is fundamentally an interactionist framework, or a theory that takes into account multiple factors when determining the outcome. For example, jealousy, like a callus, doesn’t simply pop up out of nowhere. There is an “interaction” between the environmental trigger (e.g., the flirting; the repeated rubbing of the skin) and the initial response (e.g., evaluation of the flirter’s threat; the forming of new skin cells) to produce the outcome.

In evolutionary psychology, culture also has a major effect on psychological adaptations. For example, status within one’s group is important in all cultures for achieving reproductive success, because higher status makes someone more attractive to mates. In individualistic cultures, such as the United States, status is heavily determined by individual accomplishments. But in more collectivist cultures, such as Japan, status is more heavily determined by contributions to the group and by that group’s success. For example, consider a group project. If you were to put in most of the effort on a successful group project, the culture in the United States reinforces the psychological adaptation to try to claim that success for yourself (because individual achievements are rewarded with higher status). However, the culture in Japan reinforces the psychological adaptation to attribute that success to the whole group (because collective achievements are rewarded with higher status). Another example of cultural input is the importance of virginity as a desirable quality for a mate. Cultural norms that advise against premarital sex persuade people to ignore their own basic interests because they know that virginity will make them more attractive marriage partners. Evolutionary psychology, in short, does not predict rigid robotic-like “instincts.” That is, there isn’t one rule that works all the time. Rather, evolutionary psychology studies flexible, environmentally-connected and culturally-influenced adaptations that vary according to the situation.

Psychological adaptations are hypothesized to be wide-ranging, and include food preferences, habitat preferences, mate preferences, and specialized fears. These psychological adaptations also include many traits that improve people’s ability to live in groups, such as the desire to cooperate and make friends, or the inclination to spot and avoid frauds, punish rivals, establish status hierarchies, nurture children, and help genetic relatives. Research programs in evolutionary psychology develop and empirically test predictions about the nature of psychological adaptations. Below, we highlight a few evolutionary psychological theories and their associated research approaches.

Sexual Strategies Theory

Sexual strategies theory is based on sexual selection theory. It proposes that humans have evolved a list of different mating strategies, both short-term and long-term, that vary depending on culture, social context, parental influence, and personal mate value (desirability in the “mating market”).

In its initial formulation, sexual strategies theory focused on the differences between men and women in mating preferences and strategies (Buss & Schmitt, 1993). It started by looking at the minimum parental investment needed to produce a child. For women, even the minimum investment is significant: after becoming pregnant, they have to carry that child for nine months inside of them. For men, on the other hand, the minimum investment to produce the same child is considerably smaller—simply the act of sex.

These differences in parental investment have an enormous impact on sexual strategies. For a woman, the risks associated with making a poor mating choice is high. She might get pregnant by a man who will not help to support her and her children, or who might have poor-quality genes. And because the stakes are higher for a woman, wise mating decisions for her are much more valuable. For men, on the other hand, the need to focus on making wise mating decisions isn’t as important. That is, unlike women, men 1) don’t biologically have the child growing inside of them for nine months, and 2) do not have as high a cultural expectation to raise the child. This logic leads to a powerful set of predictions: In short-term mating, women will likely be choosier than men (because the costs of getting pregnant are so high), while men, on average, will likely engage in more casual sexual activities (because this cost is greatly lessened). Due to this, men will sometimes deceive women about their long-term intentions for the benefit of short-term sex, and men are more likely than women to lower their mating standards for short-term mating situations.

An extensive body of empirical evidence supports these and related predictions (Buss & Schmitt, 2011). Men express a desire for a larger number of sex partners than women do. They let less time elapse before seeking sex. They are more willing to consent to sex with strangers and are less likely to require emotional involvement with their sex partners. They have more frequent sexual fantasies and fantasize about a larger variety of sex partners. They are more likely to regret missed sexual opportunities. And they lower their standards in short-term mating, showing a willingness to mate with a larger variety of women as long as the costs and risks are low.

However, in situations where both the man and woman are interested in long-term mating, both sexes tend to invest substantially in the relationship and in their children. In these cases, the theory predicts that both sexes will be extremely choosy when pursuing a long-term mating strategy. Much empirical research supports this prediction, as well. In fact, the qualities women and men generally look for when choosing long-term mates are very similar: both want mates who are intelligent, kind, understanding, healthy, dependable, honest, loyal, loving, and adaptable.

Nonetheless, women and men do differ in their preferences for a few key qualities in long-term mating, because of somewhat distinct adaptive problems. Modern women have inherited the evolutionary trait to desire mates who possess resources, have qualities linked with acquiring resources (e.g., ambition, wealth, industriousness), and are willing to share those resources with them. On the other hand, men more strongly desire youth and health in women, as both are cues to fertility. These male and female differences are universal in humans. They were first documented in 37 different cultures, from Australia to Zambia (Buss, 1989), and have been replicated by dozens of researchers in dozens of additional cultures (for summaries, see Buss, 2012).

As we know, though, just because we have these mating preferences (e.g., men with resources; fertile women), people don’t always get what they want. There are countless other factors which influence who people ultimately select as their mate. For example, the sex ratio (the percentage of men to women in the mating pool), cultural practices (such as arranged marriages, which inhibit individuals’ freedom to act on their preferred mating strategies), the strategies of others (e.g., if everyone else is pursuing short-term sex, it’s more difficult to pursue a long-term mating strategy), and many others all influence who we select as our mates.

Sexual strategies theory—anchored in sexual selection theory— predicts specific similarities and differences in men and women’s mating preferences and strategies. Whether we seek short-term or long-term relationships, many personality, social, cultural, and ecological factors will all influence who our partners will be.

Error Management Theory

Error management theory (EMT) deals with the evolution of how we think, make decisions, and evaluate uncertain situations—that is, situations where there’s no clear answer how we should behave. Consider, for example, walking through the woods at dusk. You hear a rustle in the leaves on the path in front of you. It could be a snake. Or, it could just be the wind blowing the leaves. Because you can’t really tell why the leaves rustled, it’s an uncertain situation. The important question then is, what are the costs of errors in judgment? That is, if you conclude that it’s a dangerous snake so you avoid the leaves, the costs are minimal (i.e., you simply make a short detour around them). However, if you assume the leaves are safe and simply walk over them—when in fact it is a dangerous snake—the decision could cost you your life.

Now, think about our evolutionary history and how generation after generation was confronted with similar decisions, where one option had low cost but great reward (walking around the leaves and not getting bitten) and the other had a low reward but high cost (walking through the leaves and getting bitten). These kinds of choices are called “cost asymmetries.” If during our evolutionary history we encountered decisions like these generation after generation, over time an adaptive bias would be created: we would make sure to err in favor of the least costly (in this case, least dangerous) option (e.g., walking around the leaves). To put it another way, EMT predicts that whenever uncertain situations present us with a safer versus more dangerous decision, we will psychologically adapt to prefer choices that minimize the cost of errors.

EMT is a general evolutionary psychological theory that can be applied to many different domains of our lives, but a specific example of it is the visual descent illusion. To illustrate: Have you ever thought it would be no problem to jump off of a ledge, but as soon as you stood up there, it suddenly looked much higher than you thought? The visual descent illusion (Jackson & Cormack, 2008) states that people will overestimate the distance when looking down from a height (compared to looking up) so that people will be especially wary of falling from great heights—which would result in injury or death. Another example of EMT is the auditory looming bias: Have you ever noticed how an ambulance seems closer when it’s coming toward you, but suddenly seems far away once it’s immediately passed? With the auditory looming bias, people overestimate how close objects are when the sound is moving toward them compared to when it is moving away from them. From our evolutionary history, humans learned, “It’s better to be safe than sorry.” Therefore, if we think that a threat is closer to us when it’s moving toward us (because it seems louder), we will be quicker to act and escape. In this regard, there may be times we ran away when we didn’t need to (a false alarm), but wasting that time is a less costly mistake than not acting in the first place when a real threat does exist.

EMT has also been used to predict adaptive biases in the domain of mating. Consider something as simple as a smile. In one case, a smile from a potential mate could be a sign of sexual or romantic interest. On the other hand, it may just signal friendliness. Because of the costs to men of missing out on chances for reproduction, EMT predicts that men have a sexual overperception bias: they often misread sexual interest from a woman, when really it’s just a friendly smile or touch. In the mating domain, the sexual overperception bias is one of the best-documented phenomena. It’s been shown in studies in which men and women rated the sexual interest between people in photographs and videotaped interactions. As well, it’s been shown in the laboratory with participants engaging in actual “speed dating,” where the men interpret sexual interest from the women more often than the women actually intended it (Perilloux, Easton, & Buss, 2012). In short, EMT predicts that men, more than women, will over-infer sexual interest based on minimal cues, and empirical research confirms this adaptive mating bias.

Where Does Evolutionary Psychology Stand Today?

This chapter places a focus on heteronormative relationships with the purpose of sexual reproduction. What about relationships that are not heteronormative? We are lucky to have Dr. Sari van Anders as part of our department, and in this video, Dr. van Anders addresses this important question:

View video in full screen (opens in a new tab)

This is a large area of research. If you are interested in learning more, the Queen’s University Department of Psychology offers courses including Human Sexuality, Sexuality & Gender, and Gender, Hormones, & Behaviour.

Check Your Knowledge

To help you with your studying, we’ve included some practice questions for this module. These questions do not necessarily address all content in this module. They are intended as practice, and you are responsible for all of the content in this module even if there is no associated practice question. To promote deeper engagement with the material, we encourage you to create some questions of your own for your practice. You can then also return to these self-generated questions later in the course to test yourself.

Vocabulary

- Adaptations

- Evolved solutions to problems that historically contributed to reproductive success.

- Error management theory (EMT)

- A theory of selection under conditions of uncertainty in which recurrent cost asymmetries of judgment or inference favor the evolution of adaptive cognitive biases that function to minimize the more costly errors.

- Evolution

- Change over time. Is the definition changing?

- Gene Selection Theory

- The modern theory of evolution by selection by which differential gene replication is the defining process of evolutionary change.

- Intersexual selection

- A process of sexual selection by which evolution (change) occurs as a consequences of the mate preferences of one sex exerting selection pressure on members of the opposite sex.

- Intrasexual competition

- A process of sexual selection by which members of one sex compete with each other, and the victors gain preferential mating access to members of the opposite sex.

- Natural selection

- Differential reproductive success as a consequence of differences in heritable attributes.

- Psychological adaptations

- Mechanisms of the mind that evolved to solve specific problems of survival or reproduction; conceptualized as information processing devices.

- Sexual selection

- The evolution of characteristics because of the mating advantage they give organisms.

- Sexual strategies theory

- A comprehensive evolutionary theory of human mating that defines the menu of mating strategies humans pursue (e.g., short-term casual sex, long-term committed mating), the adaptive problems women and men face when pursuing these strategies, and the evolved solutions to these mating problems.

References

- Buss, D. M. (2012). Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 12, 1–49.

- Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (2011). Evolutionary psychology and feminism. Sex Roles, 64, 768–787.

- Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100, 204–232.

- Haselton, M. G., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Error management theory: A new perspective on biases in cross-sex mind reading. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 81–91.

- Haselton, M. G., Nettle, D., & Andrews, P. W. (2005). The evolution of cognitive bias. In D. M. Buss (Ed.), The handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 724–746). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Jackson, R. E., & Cormack, J. K. (2008). Evolved navigation theory and the environmental vertical illusion. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29, 299–304.

- Perilloux, C., Easton, J. A., & Buss, D. M. (2012). The misperception of sexual interest. Psychological Science, 23, 146–151.

This course makes use of Open Educational Resources. Information on the original source of this chapter can be found below.

Introduction to Psychology: 1st Canadian Edition was adapted by Jennifer Walinga from Charles Stangor’s textbook, Introduction to Psychology. For information about what was changed in this adaptation, refer to the Copyright statement at the bottom of the home page. This adaptation is a part of the B.C. Open Textbook Project.

In October 2012, the B.C. Ministry of Advanced Education announced its support for the creation of open textbooks for the 40 highest-enrolled first and second year subject areas in the province’s public post-secondary system.

Open textbooks are open educational resources (OER); they are instructional resources created and shared in ways so that more people have access to them. This is a different model than traditionally copyrighted materials. OER are defined as “teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use and re-purposing by others.” (Hewlett Foundation).

BCcampus’ open textbooks are openly licensed using a Creative Commons license, and are offered in various e-book formats free of charge, or as printed books that are available at cost.

For more information about this project, please contact opentext@bccampus.ca.

If you are an instructor who is using this book for a course, please fill out an adoption form.

Copyright and Acknowledgements

This material is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

This is the first chapter in the main body of the text. You can change the text, rename the chapter, add new chapters, and add new parts.

Original chapter by Anda Gershon and Renee Thompson adapted by the Queen’s University Psychology Department

This Open Access chapter was originally written for the NOBA project. Information on the NOBA project can be found below.

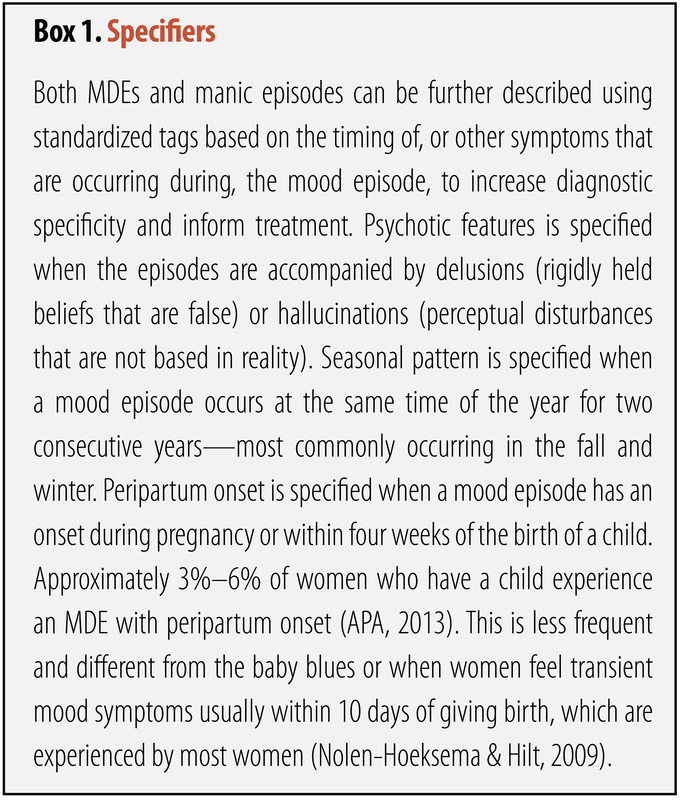

Everyone feels down or euphoric from time to time, but this is different from having a mood disorder such as major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Mood disorders are extended periods of depressed, euphoric, or irritable moods that in combination with other symptoms cause the person significant distress and interfere with his or her daily life, often resulting in social and occupational difficulties. In this module, we describe major mood disorders, including their symptom presentations, general prevalence rates, and how and why the rates of these disorders tend to vary by age, gender, and race. In addition, biological and environmental risk factors that have been implicated in the development and course of mood disorders, such as heritability and stressful life events, are reviewed. Finally, we provide an overview of treatments for mood disorders, covering treatments with demonstrated effectiveness, as well as new treatment options showing promise.

It is important to note that although "mood disorders" may be used in this chapter, the DSM-5 uses the classifications of "Depressive Disorders" and "Bipolar and Related Disorders."

What Are Mood Disorders?

Mood Episodes

Everyone experiences brief periods of sadness, irritability, or euphoria. This is different than having a mood disorder, such as MDD or BD, which are characterized by a constellation of symptoms that causes people significant distress or impairs their everyday functioning.

Major Depressive Episode

A major depressive episode (MDE) refers to symptoms that co-occur for at least two weeks and cause significant distress or impairment in functioning, such as interfering with work, school, or relationships. Core symptoms include feeling down or depressed or experiencing anhedonia—loss of interest or pleasure in things that one typically enjoys. According to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5; APA, 2013), the criteria for an MDE require five or more of the following nine symptoms, including one or both of the first two symptoms, for most of the day, nearly every day:

- depressed mood

- diminished interest or pleasure in almost all activities

- significant weight loss or gain or an increase or decrease in appetite

- insomnia or hypersomnia

- psychomotor agitation or retardation

- fatigue or loss of energy

- feeling worthless or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- diminished ability to concentrate or indecisiveness

- recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, or a suicide attempt

These symptoms cannot be caused by physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition (e.g., hypothyroidism).

Manic or Hypomanic Episode

The core criterion for a manic or hypomanic episode is a distinct period of abnormally and persistently euphoric, expansive, or irritable mood and persistently increased goal-directed activity or energy. The mood disturbance must be present for one week or longer in mania (unless hospitalization is required) or four days or longer in hypomania. Concurrently, at least three of the following symptoms must be present in the context of euphoric mood (or at least four in the context of irritable mood):

- inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- increased goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation

- reduced need for sleep

- racing thoughts or flight of ideas

- distractibility

- increased talkativeness

- excessive involvement in risky behaviors

Manic episodes are distinguished from hypomanic episodes by their duration and associated impairment; whereas manic episodes must last one week and are defined by a significant impairment in functioning, hypomanic episodes are shorter and not necessarily accompanied by impairment in functioning.

Mood Disorders

Unipolar Mood Disorders

Two major types of unipolar disorders described by the DSM-5 (APA, 2013) are major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder (PDD; dysthymia). MDD is defined by one or more MDEs, but no history of manic or hypomanic episodes. Criteria for PDD are feeling depressed most of the day for more days than not, for at least two years. At least two of the following symptoms are also required to meet criteria for PDD:

- poor appetite or overeating

- insomnia or hypersomnia

- low energy or fatigue

- low self-esteem

- poor concentration or difficulty making decisions

- feelings of hopelessness

Like MDD, these symptoms need to cause significant distress or impairment and cannot be due to the effects of a substance or a general medical condition. To meet criteria for PDD, a person cannot be without symptoms for more than two months at a time. PDD has overlapping symptoms with MDD. If someone meets criteria for an MDE during a PDD episode, the person will receive diagnoses of PDD and MDD.

Bipolar Mood Disorders

Three major types of BDs are described by the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). Bipolar I Disorder (BD I), which was previously known as manic-depression, is characterized by a single (or recurrent) manic episode. A depressive episode is not necessary but commonly present for the diagnosis of BD I. Bipolar II Disorder is characterized by single (or recurrent) hypomanic episodes and depressive episodes. Another type of BD is cyclothymic disorder, characterized by numerous and alternating periods of hypomania and depression, lasting at least two years. To qualify for cyclothymic disorder, the periods of depression cannot meet full diagnostic criteria for an MDE; the person must experience symptoms at least half the time with no more than two consecutive symptom-free months; and the symptoms must cause significant distress or impairment.

It is important to note that the DSM-5 was published in 2013, and findings based on the updated manual will be forthcoming. Consequently, the research presented below was largely based on a similar, but not identical, conceptualization of mood disorders drawn from the DSM-IV (APA, 2000).

How Common Are Mood Disorders? Who Develops Mood Disorders?

Depressive Disorders

In a nationally representative sample, lifetime prevalence rate for MDD is 16.6% (Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005). This means that nearly one in five Americans will meet the criteria for MDD during their lifetime. The 12-month prevalence—the proportion of people who meet criteria for a disorder during a 12-month period—for PDD is approximately 0.5% (APA, 2013).

Although the onset of MDD can occur at any time throughout the lifespan, the average age of onset is mid-20s, with the age of onset decreasing with people born more recently (APA, 2000). Prevalence of MDD among older adults is much lower than it is for younger cohorts (Kessler, Birnbaum, Bromet, Hwang, Sampson, & Shahly, 2010). The duration of MDEs varies widely. Recovery begins within three months for 40% of people with MDD and within 12 months for 80% (APA, 2013). MDD tends to be a recurrent disorder with about 40%–50% of those who experience one MDE experiencing a second MDE (Monroe & Harkness, 2011). An earlier age of onset predicts a worse course. About 5%–10% of people who experience an MDE will later experience a manic episode (APA, 2000), thus no longer meeting criteria for MDD but instead meeting them for BD I. Diagnoses of other disorders across the lifetime are common for people with MDD: 59% experience an anxiety disorder; 32% experience an impulse control disorder, and 24% experience a substance use disorder (Kessler, Merikangas, & Wang, 2007).

Women experience two to three times higher rates of MDD than do men (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009). This gender difference emerges during puberty (Conley & Rudolph, 2009). Before puberty, boys exhibit similar or higher prevalence rates of MDD than do girls (Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002). MDD is inversely correlated with socioeconomic status (SES), a person’s economic and social position based on income, education, and occupation. Higher prevalence rates of MDD are associated with lower SES (Lorant, Deliege, Eaton, Robert, Philippot, & Ansseau, 2003), particularly for adults over 65 years old (Kessler et al., 2010). Independent of SES, results from a nationally representative sample found that European Americans had a higher prevalence rate of MDD than did African Americans and Hispanic Americans, whose rates were similar (Breslau, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Kendler, Su, Williams, & Kessler, 2006). The course of MDD for African Americans is often more severe and less often treated than it is for European Americans, however (Williams et al., 2007). Native Americans have a higher prevalence rate than do European Americans, African Americans, or Hispanic Americans (Hasin, Goodwin, Stinson & Grant, 2005). Depression is not limited to industrialized or western cultures; it is found in all countries that have been examined, although the symptom presentation as well as prevalence rates vary across cultures (Chentsova-Dutton & Tsai, 2009).

Bipolar Disorders

The lifetime prevalence rate of bipolar spectrum disorders in the general U.S. population is estimated at approximately 4.4%, with BD I constituting about 1% of this rate (Merikangas et al., 2007). Prevalence estimates, however, are highly dependent on the diagnostic procedures used (e.g., interviews vs. self-report) and whether or not sub-threshold forms of the disorder are included in the estimate. BD often co-occurs with other psychiatric disorders. Approximately 65% of people with BD meet diagnostic criteria for at least one additional psychiatric disorder, most commonly anxiety disorders and substance use disorders (McElroy et al., 2001). The co-occurrence of BD with other psychiatric disorders is associated with poorer illness course, including higher rates of suicidality (Leverich et al., 2003). A recent cross-national study sample of more than 60,000 adults from 11 countries, estimated the worldwide prevalence of BD at 2.4%, with BD I constituting 0.6% of this rate (Merikangas et al., 2011). In this study, the prevalence of BD varied somewhat by country. Whereas the United States had the highest lifetime prevalence (4.4%), India had the lowest (0.1%). Variation in prevalence rates was not necessarily related to SES, as in the case of Japan, a high-income country with a very low prevalence rate of BD (0.7%).

With regard to ethnicity, data from studies not confounded by SES or inaccuracies in diagnosis are limited, but available reports suggest rates of BD among European Americans are similar to those found among African Americans (Blazer et al., 1985) and Hispanic Americans (Breslau, Kendler, Su, Gaxiola-Aguilar, & Kessler, 2005). Another large community-based study found that although prevalence rates of mood disorders were similar across ethnic groups, Hispanic Americans and African Americans with a mood disorder were more likely to remain persistently ill than European Americans (Breslau et al., 2005). Compared with European Americans with BD, African Americans tend to be underdiagnosed for BD (and over-diagnosed for schizophrenia) (Kilbourne, Haas, Mulsant, Bauer, & Pincus, 2004; Minsky, Vega, Miskimen, Gara, & Escobar, 2003), and Hispanic Americans with BD have been shown to receive fewer psychiatric medication prescriptions and specialty treatment visits (Gonzalez et al., 2007). Misdiagnosis of BD can result in the underutilization of treatment or the utilization of inappropriate treatment, and thus profoundly impact the course of illness.

As with MDD, adolescence is known to be a significant risk period for BD; mood symptoms start by adolescence in roughly half of BD cases (Leverich et al., 2007; Perlis et al., 2004). Longitudinal studies show that those diagnosed with BD prior to adulthood experience a more pernicious course of illness relative to those with adult onset, including more episode recurrence, higher rates of suicidality, and profound social, occupational, and economic repercussions (e.g., Lewinsohn, Seeley, Buckley, & Klein, 2002). The prevalence of BD is substantially lower in older adults compared with younger adults (1% vs. 4%) (Merikangas et al., 2007).

What Are Some of the Factors Implicated in the Development and Course of Mood Disorders?

Mood disorders are complex disorders resulting from multiple factors. Causal explanations can be attempted at various levels, including biological and psychosocial levels. Below are several of the key factors that contribute to onset and course of mood disorders are highlighted.

Depressive Disorders

Research across family and twin studies has provided support that genetic factors are implicated in the development of MDD. Twin studies suggest that familial influence on MDD is mostly due to genetic effects and that individual-specific environmental effects (e.g., romantic relationships) play an important role, too. By contrast, the contribution of shared environmental effect by siblings is negligible (Sullivan, Neale & Kendler, 2000) The mode of inheritance is not fully understood although no single genetic variation has been found to increase the risk of MDD significantly. Instead, several genetic variants and environmental factors most likely contribute to the risk for MDD (Lohoff, 2010).

One environmental stressor that has received much support in relation to MDD is stressful life events. In particular, severe stressful life events—those that have long-term consequences and involve loss of a significant relationship (e.g., divorce) or economic stability (e.g., unemployment) are strongly related to depression (Brown & Harris, 1989; Monroe et al., 2009). Stressful life events are more likely to predict the first MDE than subsequent episodes (Lewinsohn, Allen, Seeley, & Gotlib, 1999). In contrast, minor events may play a larger role in subsequent episodes than the initial episodes (Monroe & Harkness, 2005).

Depression research has not been limited to examining reactivity to stressful life events. Much research, particularly brain imagining research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), has centered on examining neural circuitry—the interconnections that allow multiple brain regions to perceive, generate, and encode information in concert. A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies showed that when viewing negative stimuli (e.g., picture of an angry face, picture of a car accident), compared with healthy control participants, participants with MDD have greater activation in brain regions involved in stress response and reduced activation of brain regions involved in positively motivated behaviors (Hamilton, Etkin, Furman, Lemus, Johnson, & Gotlib, 2012).

Other environmental factors related to increased risk for MDD include experiencing early adversity (e.g., childhood abuse or neglect; Widom, DuMont, & Czaja, 2007), chronic stress (e.g., poverty) and interpersonal factors. For example, marital dissatisfaction predicts increases in depressive symptoms in both men and women. On the other hand, depressive symptoms also predict increases in marital dissatisfaction (Whisman & Uebelacker, 2009). Research has found that people with MDD generate some of their interpersonal stress (Hammen, 2005). People with MDD whose relatives or spouses can be described as critical and emotionally overinvolved have higher relapse rates than do those living with people who are less critical and emotionally overinvolved (Butzlaff & Hooley, 1998).

People’s attributional styles or their general ways of thinking, interpreting, and recalling information have also been examined in the etiology of MDD (Gotlib & Joormann, 2010). People with a pessimistic attributional style tend to make internal (versus external), global (versus specific), and stable (versus unstable) attributions to negative events, serving as a vulnerability to developing MDD. For example, someone who when he fails an exam thinks that it was his fault (internal), that he is stupid (global), and that he will always do poorly (stable) has a pessimistic attribution style. Several influential theories of depression incorporate attributional styles (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989; Abramson Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978).

Bipolar Disorders

Although there have been important advances in research on the etiology, course, and treatment of BD, there remains a need to understand the mechanisms that contribute to episode onset and relapse. There is compelling evidence for biological causes of BD, which is known to be highly heritable (McGuffin, Rijsdijk, Andrew, Sham, Katz, & Cardno, 2003). It may be argued that a high rate of heritability demonstrates that BD is fundamentally a biological phenomenon. However, there is much variability in the course of BD both within a person across time and across people (Johnson, 2005). The triggers that determine how and when this genetic vulnerability is expressed are not yet understood; however, there is evidence to suggest that psychosocial triggers may play an important role in BD risk (e.g., Johnson et al., 2008; Malkoff-Schwartz et al., 1998).

In addition to the genetic contribution, biological explanations of BD have also focused on brain function. Many of the studies using fMRI techniques to characterize BD have focused on the processing of emotional stimuli based on the idea that BD is fundamentally a disorder of emotion (APA, 2000). Findings show that regions of the brain thought to be involved in emotional processing and regulation are activated differently in people with BD relative to healthy controls (e.g., Altshuler et al., 2008; Hassel et al., 2008; Lennox, Jacob, Calder, Lupson, & Bullmore, 2004).

However, there is little consensus as to whether a particular brain region becomes more or less active in response to an emotional stimulus among people with BD compared with healthy controls. Mixed findings are in part due to samples consisting of participants who are at various phases of illness at the time of testing (manic, depressed, inter-episode). Sample sizes tend to be relatively small, making comparisons between subgroups difficult. Additionally, the use of a standardized stimulus (e.g., facial expression of anger) may not elicit a sufficiently strong response. Personally engaging stimuli, such as recalling a memory, may be more effective in inducing strong emotions (Isacowitz, Gershon, Allard, & Johnson, 2013).

Within the psychosocial level, research has focused on the environmental contributors to BD. A series of studies show that environmental stressors, particularly severe stressors (e.g., loss of a significant relationship), can adversely impact the course of BD. People with BD have substantially increased risk of relapse (Ellicott, Hammen, Gitlin, Brown, & Jamison, 1990) and suffer more depressive symptoms (Johnson, Winett, Meyer, Greenhouse, & Miller, 1999) following a severe life stressor. Interestingly, positive life events can also adversely impact the course of BD. People with BD suffer more manic symptoms after life events involving attainment of a desired goal (Johnson et al., 2008). Such findings suggest that people with BD may have a hypersensitivity to rewards.

Evidence from the life stress literature has also suggested that people with mood disorders may have a circadian vulnerability that renders them sensitive to stressors that disrupt their sleep or rhythms. According to social zeitgeber theory (Ehlers, Frank, & Kupfer, 1988; Frank et al., 1994), stressors that disrupt sleep, or that disrupt the daily routines that entrain the biological clock (e.g., meal times) can trigger episode relapse. Consistent with this theory, studies have shown that life events that involve a disruption in sleep and daily routines, such as overnight travel, can increase bipolar symptoms in people with BD (Malkoff-Schwartz et al., 1998).

What Are Some of the Well-Supported Treatments for Mood Disorders?

Depressive Disorders

There are many treatment options available for people with MDD. First, a number of antidepressant medications are available, all of which target one or more of the neurotransmitters implicated in depression.The earliest antidepressant medications were monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). MAOIs inhibit monoamine oxidase, an enzyme involved in deactivating dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. Although effective in treating depression, MAOIs can have serious side effects. Patients taking MAOIs may develop dangerously high blood pressure if they take certain drugs (e.g., antihistamines) or eat foods containing tyramine, an amino acid commonly found in foods such as aged cheeses, wine, and soy sauce. Tricyclics, the second-oldest class of antidepressant medications, block the reabsorption of norepinephrine, serotonin, or dopamine at synapses, resulting in their increased availability. Tricyclics are most effective for treating vegetative and somatic symptoms of depression. Like MAOIs, they have serious side effects, the most concerning of which is being cardiotoxic. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; e.g., Fluoxetine) and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs; e.g., Duloxetine) are the most recently introduced antidepressant medications. SSRIs, the most commonly prescribed antidepressant medication, block the reabsorption of serotonin, whereas SNRIs block the reabsorption of serotonin and norepinephrine. SSRIs and SNRIs have fewer serious side effects than do MAOIs and tricyclics. In particular, they are less cardiotoxic, less lethal in overdose, and produce fewer cognitive impairments. They are not, however, without their own side effects, which include but are not limited to difficulty having orgasms, gastrointestinal issues, and insomnia.

Other biological treatments for people with depression include electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and deep brain stimulation. ECT involves inducing a seizure after a patient takes muscle relaxants and is under general anesthesia. ECT is viable treatment for patients with severe depression or who show resistance to antidepressants although the mechanisms through which it works remain unknown. A common side effect is confusion and memory loss, usually short-term (Schulze-Rauschenbach, Harms, Schlaepfer, Maier, Falkai, & Wagner, 2005). Repetitive TMS is a noninvasive technique administered while a patient is awake. Brief pulsating magnetic fields are delivered to the cortex, inducing electrical activity. TMS has fewer side effects than ECT (Schulze-Rauschenbach et al., 2005), and while outcome studies are mixed, there is evidence that TMS is a promising treatment for patients with MDD who have shown resistance to other treatments (Rosa et al., 2006). Most recently, deep brain stimulation is being examined as a treatment option for patients who did not respond to more traditional treatments like those already described. Deep brain stimulation involves implanting an electrode in the brain. The electrode is connected to an implanted neurostimulator, which electrically stimulates that particular brain region. Although there is some evidence of its effectiveness (Mayberg et al., 2005), additional research is needed.

Several psychosocial treatments have received strong empirical support, meaning that independent investigations have achieved similarly positive results—a high threshold for examining treatment outcomes. These treatments include but are not limited to behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, and interpersonal therapy. Behavior therapies focus on increasing the frequency and quality of experiences that are pleasant or help the patient achieve mastery. Cognitive therapies primarily focus on helping patients identify and change distorted automatic thoughts and assumptions (e.g., Beck, 1967). Cognitive-behavioral therapies are based on the rationale that thoughts, behaviors, and emotions affect and are affected by each other. Interpersonal Therapy for Depression focuses largely on improving interpersonal relationships by targeting problem areas, specifically unresolved grief, interpersonal role disputes, role transitions, and interpersonal deficits. Finally, there is also some support for the effectiveness of Short-Term Psychodynamic Therapy for Depression (Leichsenring, 2001). The short-term treatment focuses on a limited number of important issues, and the therapist tends to be more actively involved than in more traditional psychodynamic therapy.

Bipolar Disorders

Patients with BD are typically treated with pharmacotherapy. Antidepressants such as SSRIs and SNRIs are the primary choice of treatment for depression, whereas for BD, lithium is the first line treatment choice. This is because SSRIs and SNRIs have the potential to induce mania or hypomania in patients with BD. Lithium acts on several neurotransmitter systems in the brain through complex mechanisms, including reduction of excitatory (dopamine and glutamate) neurotransmission, and increasing of inhibitory (GABA) neurotransmission (Lenox & Hahn, 2000). Lithium has strong efficacy for the treatment of BD (Geddes, Burgess, Hawton, Jamison, & Goodwin, 2004). However, a number of side effects can make lithium treatment difficult for patients to tolerate. Side effects include impaired cognitive function (Wingo, Wingo, Harvey, & Baldessarini, 2009), as well as physical symptoms such as nausea, tremor, weight gain, and fatigue (Dunner, 2000). Some of these side effects can improve with continued use; however, medication noncompliance remains an ongoing concern in the treatment of patients with BD. Anticonvulsant medications (e.g., carbamazepine, valproate) are also commonly used to treat patients with BD, either alone or in conjunction with lithium.

There are several adjunctive treatment options for people with BD. Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT; Frank et al., 1994) is a psychosocial intervention focused on addressing the mechanism of action posited in social zeitgeber theory to predispose patients who have BD to relapse, namely sleep disruption. A growing body of literature provides support for the central role of sleep dysregulation in BD (Harvey, 2008). Consistent with this literature, IPSRT aims to increase rhythmicity of patients’ lives and encourage vigilance in maintaining a stable rhythm. The therapist and patient work to develop and maintain a healthy balance of activity and stimulation such that the patient does not become overly active (e.g., by taking on too many projects) or inactive (e.g., by avoiding social contact). The efficacy of IPSRT has been demonstrated in that patients who received this treatment show reduced risk of episode recurrence and are more likely to remain well (Frank et al., 2005).

Conclusion

Everyone feels down or euphoric from time to time. For some people, these feelings can last for long periods of time and can also co-occur with other symptoms that, in combination, interfere with their everyday lives. When people experience an MDE or a manic episode, they see the world differently. During an MDE, people often feel hopeless about the future, and may even experience suicidal thoughts. During a manic episode, people often behave in ways that are risky or place them in danger. They may spend money excessively or have unprotected sex, often expressing deep shame over these decisions after the episode. MDD and BD cause significant problems for people at school, at work, and in their relationships and affect people regardless of gender, age, nationality, race, religion, or sexual orientation. If you or someone you know is suffering from a mood disorder, it is important to seek help. Effective treatments are available and continually improving. If you have an interest in mood disorders, there are many ways to contribute to their understanding, prevention, and treatment, whether by engaging in research or clinical work.

Check Your Knowledge

To help you with your studying, we’ve included some practice questions for this module. These questions do not necessarily address all content in this module. They are intended as practice, and you are responsible for all of the content in this module even if there is no associated practice question. To promote deeper engagement with the material, we encourage you to create some questions of your own for your practice. You can then also return to these self-generated questions later in the course to test yourself.

Vocabulary

- Anhedonia

- Loss of interest or pleasure in activities one previously found enjoyable or rewarding.

- Attributional style

- The tendency by which a person infers the cause or meaning of behaviors or events.

- Chronic stress

- Discrete or related problematic events and conditions which persist over time and result in prolonged activation of the biological and/or psychological stress response (e.g., unemployment, ongoing health difficulties, marital discord).

- Early adversity

- Single or multiple acute or chronic stressful events, which may be biological or psychological in nature (e.g., poverty, abuse, childhood illness or injury), occurring during childhood and resulting in a biological and/or psychological stress response.

- Grandiosity

- Inflated self-esteem or an exaggerated sense of self-importance and self-worth (e.g., believing one has special powers or superior abilities).

- Hypersomnia

- Excessive daytime sleepiness, including difficulty staying awake or napping, or prolonged sleep episodes.

- Psychomotor agitation

- Increased motor activity associated with restlessness, including physical actions (e.g., fidgeting, pacing, feet tapping, handwringing).

- Psychomotor retardation

- A slowing of physical activities in which routine activities (e.g., eating, brushing teeth) are performed in an unusually slow manner.

- Zeitgeber is German for “time giver.” Social zeitgebers are environmental cues, such as meal times and interactions with other people, that entrain biological rhythms and thus sleep-wake cycle regularity.

- Socioeconomic status (SES)

- A person’s economic and social position based on income, education, and occupation.

- Suicidal ideation

- Recurring thoughts about suicide, including considering or planning for suicide, or preoccupation with suicide.

References

- Abramson, L. Y, Seligman, M. E. P., & Teasdale, J. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49–74. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.87.1.49

- Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96, 358–373. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.3.431

- Altshuler, L., Bookheimer, S., Townsend, J., Proenza, M. A., Sabb, F., Mintz, J., & Cohen, M. S. (2008). Regional brain changes in bipolar I depression: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Bipolar Disorders, 10, 708–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00617.x

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. New York, NY: Hoeber.

- Blazer, D., George, L. K., Landerman, R., Pennybacker, M., Melville, M. L., Woodbury, M., et al. (1985). Psychiatric disorders. A rural/urban comparison. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42, 651–656. PMID: 4015306. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300013002

- Breslau, J., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Kendler, K. S., Su, M., Williams, D., & Kessler, R. C. (2006). Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a US national sample. Psychological Medicine, 36, 57–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006161

- Breslau, J., Kendler, K. S., Su, M., Gaxiola-Aguilar, S., & Kessler, R. C. (2005). Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychological Medicine, 35, 317–327. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704003514

- Brown, G. W., & Harris, T. O. (1989). Life events and illness. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Butzlaff, R. L., & Hooley, J. M. (1998). Expressed emotion and psychiatric relapse: A meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 547–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.6.547

- Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E., & Tsai, J. L. (2009). Understanding depression across cultures. In I. H. Gotlib & C.L. Hammen (Eds.), Handbook of depression (2nd ed., pp. 363–385). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Conley, C. S., & Rudolph, K. D. (2009). The emerging sex difference in adolescent depression: Interacting contributions of puberty and peer stress. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 593–620. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000327

- Dunner, D. L. (2000). Optimizing lithium treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(S9), 76–81.

- Ehlers, C. L., Frank, E., & Kupfer, D. J. (1988). Social zeitgebers and biological rhythms: a unified approach to understanding the etiology of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 45, 948–952. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800340076012

- Ellicott, A., Hammen, C., Gitlin, M., Brown, G., & Jamison, K. (1990). Life events and the course of bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 1194–1198.

- Frank, E., Kupfer, D. J., Ehlers, C. L., Monk, T., Cornes, C., Carter, S., et al. (1994). Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy for bipolar disorder: Integrating interpersonal and behavioral approaches. Behavior Therapy, 17, 143–149.

- Frank, E., Kupfer, D. J., Thase, M. E., Mallinger, A. G., Swartz, H. A., Fagiolini, A. M., et al. (2005). Two-year outcomes for interpersonal and social rhythm therapy in individuals with bipolar I disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 996–1004. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.996

- Geddes, J. R., Burgess, S., Hawton, K., Jamison, K., & Goodwin, G. M. (2004). Long-term lithium therapy for bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 217–222. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.217

- Gonzalez, J. M., Perlick, D. A., Miklowitz, D. J., Kaczynski, R., Hernandez, M., Rosenheck, R. A., et al. (2007). Factors associated with stigma among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder in the STEP-BD study. Psychiatric Services, 58, 41–48. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.1.41

- Goodwin, F. K., & Jamison, K. R. (2007). Manic-depressive illness: Bipolar disorders and recurrent depression. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Gotlib, I. H., & Joormann, J. (2010). Cognition and depression: Current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 285–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131305

- Hamilton, J. P., Etkin, A., Furman, D. F., Lemus, M. G., Johnson, R. F., & Gotlib, I. H. (2012). Functional neuroimaging of major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis and new integration of baseline activation and neural response data. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169, 693–703.

- Hammen, C. (2005). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938

- Harvey, A. G. (2008). Sleep and Circadian Rhythms in Bipolar Disorder: Seeking synchrony, harmony and regulation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 820–829. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010098

- Hasin, D. S., Goodwin, R. D., Sintson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. (2005). Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097

- Hassel, S., Almeida, J. R., Kerr, N., Nau, S., Ladouceur, C. D., Fissell, K., et al. (2008). Elevated striatal and decreased dorsolateral prefrontal cortical activity in response to emotional stimuli in euthymic bipolar disorder: No associations with psychotropic medication load. Bipolar Disorders, 10, 916–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00641.x

- Isaacowitz, D. M., Gershon, A., Allard, E. S., & Johnson, S. L. (2013). Emotion in aging and bipolar disorder: Similarities, differences and lessons for further research. Emotion Review, 5, 312–320. doi: 10.1177/1754073912472244

- Johnson, S. L. (2005). Mania and dysregulation in goal pursuit: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25, 241–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.11.002

- Johnson, S. L., Cueller, A. K., Ruggero, C., Winett-Perlman, C., Goodnick, P., White, R., et al. (2008). Life events as predictors of mania and depression in bipolar I disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 268–277. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.268

- Johnson, S. L., Winett, C. A., Meyer, B., Greenhouse, W. J., & Miller, I. (1999). Social support and the course of bipolar disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 558–566. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.4.558

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jim, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

- Kessler, R. C., Birnbaum, H., Bromet, E., Hwang, I., Sampson, N., & Shahly, V. (2010). Age differences in major depression: Results from the National Comorbidity Surveys Replication (NCS-R). Psychological Medicine, 40, 225–237. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990213

- Kessler, R. C., Merikangas, K. R., & Wang, P. S. (2007). Prevalence, comorbidity, and service utilization for mood disorders in the United States at the beginning of the 21st century. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 137–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091444

- Kilbourne, A. M., Haas, G. L., Mulsant, B. H., Bauer, M. S., & Pincus, H. A. (2004) Concurrent psychiatric diagnoses by age and race among persons with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services, 55, 931–933. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.931

- Leichsenring, F. (2001). Comparative effects of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy in depression: A meta-analytic approach. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 401–419. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00057-4

- Lennox, B. R., Jacob, R., Calder, A. J., Lupson, V., & Bullmore, E. T. (2004). Behavioural and neurocognitive responses to sad facial affect are attenuated in patients with mania. Psychological Medicine, 34, 795–802. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704002557

- Lenox, R. H., & Hahn C. G. (2000). Overview of the mechanism of action of lithium in the brain: fifty-year update. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61 (S9), 5–15.

- Leverich, G. S., Altshuler, L. L., Frye, M. A., Suppes, T., Keck, P. E. Jr, McElroy, S. L., et al. (2003). Factors associated with suicide attempts in 648 patients with bipolar disorder in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 506–515. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v64n0503

- Leverich, G. S., Post, R. M., Keck, P. E. Jr, Altshuler, L. L., Frye, M. A., Kupka, R. W., et al. (2007). The poor prognosis of childhood-onset bipolar disorder. Journal of Pediatrics, 150, 485–490. PMID: 17452221. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.10.070

- Lewinsohn, P. M., Allen, N. B., Seeley, J. R., & Gotlib, I. H. (1999). First onset versus recurrence of depression: differential processes of psychosocial risk. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 483–489. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.3.483

- Lewinsohn, P. M., Seeley, J. R., Buckley, M. E., & Klein, D. N. (2002). Bipolar disorder in adolescence and young adulthood. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 11, 461–475. doi: 10.1016/S1056-4993(02)00005-6

- Lohoff, F. W. (2010). Overview of genetics of major depressive disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 12, 539–546. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0150-6

- Lorant, V., Deliege, D., Eaton, W., Robert, A., Philippot, P., & Ansseau, A. (2003). Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157, 98–112. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf182

- Malkoff-Schwartz, S., Frank, E., Anderson, B. P., Sherrill, J. T., Siegel, L., Patterson, D., et al. (1998). Stressful life events and social rhythm disruption in the onset of manic and depressive bipolar episodes: a preliminary investigation. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 702–707. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.702

- Mayberg, H. S., Lozano, A. M., Voon, V., McNeely, H. E., Seminowixz, D., Hamani, C., Schwalb, J. M., & Kennedy, S. H. (2005). Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron, 45, 651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.014

- McElroy, S. L., Altshuler, L. L., Suppes, T., Keck, P. E. Jr, Frye, M. A., Denicoff, K. D., et al. (2001). Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 420–426. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.420

- McGuffin, P., Rijsdijk, F., Andrew, M., Sham, P., Katz, R., Cardno, A. (2003). The heritability of bipolar affective disorder and the genetic relationship to unipolar depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 497–502. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.497

- Merikangas, K. R., Akiskal, H. S., Angst, J., Greenberg, P. E., Hirschfeld, R. M., Petukhova, M., et al. (2007). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543

- Merikangas, K. R., Jin, R., He, J. P., Kessler, R. C., Lee, S., Sampson, N. A., et al. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68, 241–251. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.12

- Minsky, S., Vega, W., Miskimen, T., Gara, M., & Escobar, J. (2003). Diagnostic patterns in Latino, African American, and European American psychiatric patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 637–644. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.637

- Monroe, S. M., & Harkness, K. L. (2011). Recurrence in major depression: A conceptual analysis. Psychological Review, 118, 655–674. doi: 10.1037/a0025190

- Monroe, S. M., & Harkness, K. L. (2005). Life stress, the “Kindling” hypothesis, and the recurrence of depression: Considerations from a life stress perspective. Psychological Review, 112, 417–445. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.2.417

- Monroe, S.M., Slavich, G.M., Georgiades, K. (2009). The social environment and life stress in depression. In Gotlib, I.H., Hammen, C.L (Eds.) Handbook of depression (2nd ed., pp. 340-360). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Hilt, L. M. (2009). Gender differences in depression. In I. H. Gotlib & Hammen, C. L. (Eds.), Handbook of depression (2nd ed., pp. 386–404). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Perlis, R. H., Miyahara, S., Marangell, L. B., Wisniewski, S. R., Ostacher, M., DelBello, M. P., et al. (2004). Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD). Biological Psychiatry, 55, 875–881. PMID: 15110730. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.10.003

- Rosa, M. A., Gattaz, W. F., Pascual-Leone, A., Fregni, F., Rosa, M. O., Rumi, D. O., … Marcolin, M. A. (2006). Comparison of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroconvulsive therapy in unipolar non-psychotic refractory depression: a randomized, single-blind study. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 9, 667–676. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706007127

- Schulze-Rauschenbach, S. C., Harms, U., Schlaepfer, T. E., Maier, W., Falkai, P., & Wagner, M. (2005). Distinctive neurocognitive effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 410–416. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.5.410

- Shields, B. (2005). Down Came the Rain: My Journey Through Postpartum Depression. New York: Hyperion.

- Sullivan, P., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2000). Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1552–1562. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552

- Twenge, J. M., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2002). Age, gender, race, SES, and birth cohort differences on the Children’s Depression Inventory: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 578–588. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.4.578

- Whisman, M. A., & Uebelacker, L. A. (2009). Prospective associations between marital discord and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 24, 184–189. doi: 10.1037/a0014759

- Widom, C. S., DuMont, K., & Czaja, S. J. (2007). A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 49–56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.49

- Williams, D. R., Gonzalez, H. M., Neighbors, H., Nesse, R., Abelson, J. M., Sweetman, J., & Jackson, J. S. (2007). Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305

- Wingo, A. P., Wingo, T. S., Harvey, P. D., & Baldessarini, R. J. (2009). Effects of lithium on cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70, 1588–1597. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08r04972

How to cite this Chapter using APA Style:

Gershon, A. & Thompson, R. (2019). Depressive Disorders & Bipolar and Related Disorders. Adapted for use by Queen’s University. Original chapter in R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from https://nobaproject.com/modules/mood-disorders

Copyright and Acknowledgment:

This material is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.en_US.

This material is attributed to the Diener Education Fund (copyright © 2018) and can be accessed via this link: http://noba.to/5d98nsy4.

Additional information about the Diener Education Fund (DEF) can be accessed here.