5 The Nature-Nurture Question

Original chapter by Eric Turkheimer adapted by the Queen’s University Psychology Department

This Open Access chapter was originally written for the NOBA project. Information on the NOBA project can be found below.

People have a deep intuition about what has been called the “nature–nurture question.” Some aspects of our behavior feel as though they originate in our genetic makeup, while others feel like the result of our upbringing or our own hard work. The scientific field of behavior genetics attempts to study these differences empirically, either by examining similarities among family members with different degrees of genetic relatedness, or, more recently, by studying differences in the DNA of people with different behavioral traits. The scientific methods that have been developed are ingenious, but often inconclusive. Many of the difficulties encountered in the empirical science of behavior genetics turn out to be conceptual, and our intuitions about nature and nurture get more complicated the harder we think about them. In the end, it is an oversimplification to ask how “genetic” some particular behavior is. Genes and environments always combine to produce behavior, and the real science is in the discovery of how they combine for a given behavior.

Learning Objectives

- Understand what the nature–nurture debate is and why the problem fascinates us.

- Understand why nature–nurture questions are difficult to study empirically.

- Know the major research designs that can be used to study nature–nurture questions.

- Appreciate the complexities of nature–nurture and why questions that seem simple turn out not to have simple answers.

Introduction

There are three related problems at the intersection of philosophy and science that are fundamental to our understanding of our relationship to the natural world: the mind–body problem, the free will problem, and the nature–nurture problem. These great questions have a lot in common. Everyone, even those without much knowledge of science or philosophy, has opinions about the answers to these questions that come simply from observing the world we live in. Our feelings about our relationship with the physical and biological world often seem incomplete. We are in control of our actions in some ways, but at the mercy of our bodies in others; it feels obvious that our consciousness is some kind of creation of our physical brains, at the same time we sense that our awareness must go beyond just the physical. This incomplete knowledge of our relationship with nature leaves us fascinated and a little obsessed, like a cat that climbs into a paper bag and then out again, over and over, mystified every time by a relationship between inner and outer that it can see but can’t quite understand.

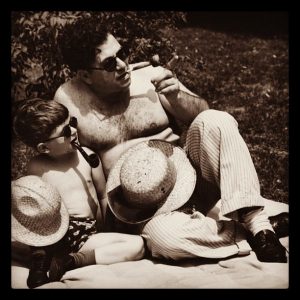

It may seem obvious that we are born with certain characteristics while others are acquired, and yet of the three great questions about humans’ relationship with the natural world, only nature–nurture gets referred to as a “debate.” In the history of psychology, no other question has caused so much controversy and offense: We are so concerned with nature–nurture because our very sense of moral character seems to depend on it. While we may admire the athletic skills of a great basketball player, we think of his height as simply a gift, a payoff in the “genetic lottery.” For the same reason, no one blames a short person for his height or someone’s congenital disability on poor decisions: To state the obvious, it’s “not their fault.” But we do praise the concert violinist (and perhaps her parents and teachers as well) for her dedication, just as we condemn cheaters, slackers, and bullies for their bad behavior.

The problem is, most human characteristics aren’t usually as clear-cut as height or instrument-mastery, affirming our nature–nurture expectations strongly one way or the other. In fact, even the great violinist might have some inborn qualities—perfect pitch, or long, nimble fingers—that support and reward her hard work. And the basketball player might have eaten a diet while growing up that promoted his genetic tendency for being tall. When we think about our own qualities, they seem under our control in some respects, yet beyond our control in others. And often the traits that don’t seem to have an obvious cause are the ones that concern us the most and are far more personally significant. What about how much we drink or worry? What about our honesty, or religiosity, or sexual orientation? They all come from that uncertain zone, neither fixed by nature nor totally under our own control.

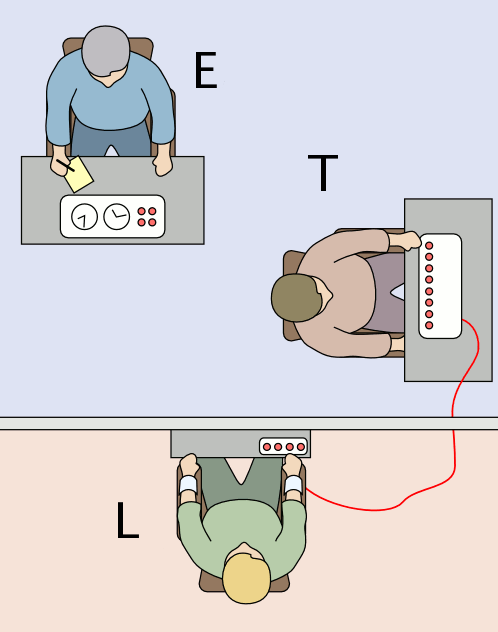

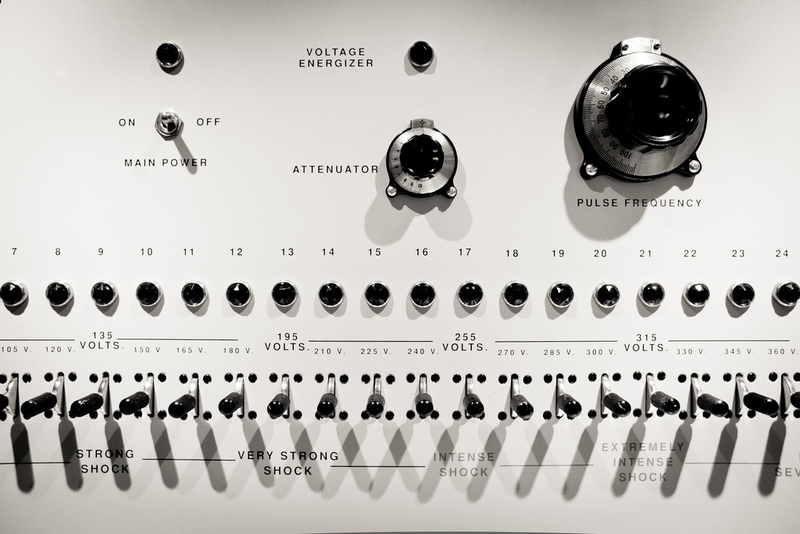

One major problem with answering nature-nurture questions about people is, how do you set up an experiment? In nonhuman animals, there are relatively straightforward experiments for tackling nature–nurture questions. Say, for example, you are interested in aggressiveness in dogs. You want to test for the more important determinant of aggression: being born to aggressive dogs or being raised by them. You could mate two aggressive dogs—angry Chihuahuas—together, and mate two nonaggressive dogs—happy beagles—together, then switch half the puppies from each litter between the different sets of parents to raise. You would then have puppies born to aggressive parents (the Chihuahuas) but being raised by nonaggressive parents (the Beagles), and vice versa, in litters that mirror each other in puppy distribution. The big questions are: Would the Chihuahua parents raise aggressive beagle puppies? Would the beagle parents raise nonaggressive Chihuahua puppies? Would the puppies’ nature win out, regardless of who raised them? Or… would the result be a combination of nature and nurture? Much of the most significant nature–nurture research has been done in this way (Scott & Fuller, 1998), and animal breeders have been doing it successfully for thousands of years. In fact, it is fairly easy to breed animals for behavioral traits.

With people, however, we can’t assign babies to parents at random, or select parents with certain behavioral characteristics to mate, merely in the interest of science (though history does include horrific examples of such practices, in misguided attempts at “eugenics,” the shaping of human characteristics through intentional breeding). In typical human families, children’s biological parents raise them, so it is very difficult to know whether children act like their parents due to genetic (nature) or environmental (nurture) reasons. Nevertheless, despite our restrictions on setting up human-based experiments, we do see real-world examples of nature-nurture at work in the human sphere—though they only provide partial answers to our many questions.

The science of how genes and environments work together to influence behavior is called behavioral genetics. The easiest opportunity we have to observe this is the adoption study. When children are put up for adoption, the parents who give birth to them are no longer the parents who raise them. This setup isn’t quite the same as the experiments with dogs (children aren’t assigned to random adoptive parents in order to suit the particular interests of a scientist) but adoption still tells us some interesting things, or at least confirms some basic expectations. For instance, if the biological child of tall parents were adopted into a family of short people, do you suppose the child’s growth would be affected? What about the biological child of a Spanish-speaking family adopted at birth into an English-speaking family? What language would you expect the child to speak? And what might these outcomes tell you about the difference between height and language in terms of nature-nurture?

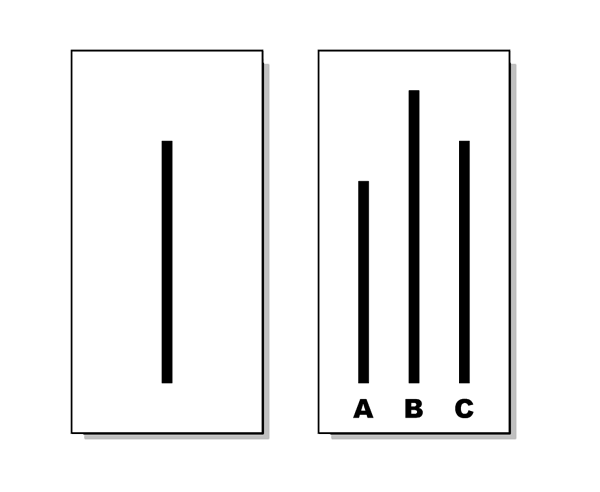

Another option for observing nature-nurture in humans involves twin studies. There are two types of twins: monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ). Monozygotic twins, also called “identical” twins, result from a single zygote (fertilized egg) and have the same DNA. They are essentially clones. Dizygotic twins, also known as “fraternal” twins, develop from two zygotes and share 50% of their DNA. Fraternal twins are ordinary siblings who happen to have been born at the same time. To analyze nature–nurture using twins, we compare the similarity of MZ and DZ pairs. Sticking with the features of height and spoken language, let’s take a look at how nature and nurture apply: Identical twins, unsurprisingly, are almost perfectly similar for height. The heights of fraternal twins, however, are like any other sibling pairs: more similar to each other than to people from other families, but hardly identical. This contrast between twin types gives us a clue about the role genetics plays in determining height. Now consider spoken language. If one identical twin speaks Spanish at home, the co-twin with whom she is raised almost certainly does too. But the same would be true for a pair of fraternal twins raised together. In terms of spoken language, fraternal twins are just as similar as identical twins, so it appears that the genetic match of identical twins doesn’t make much difference.

Twin and adoption studies are two instances of a much broader class of methods for observing nature-nurture called quantitative genetics, the scientific discipline in which similarities among individuals are analyzed based on how biologically related they are. We can do these studies with siblings and half-siblings, cousins, twins who have been separated at birth and raised separately (Bouchard, Lykken, McGue, & Segal, 1990; such twins are very rare and play a smaller role than is commonly believed in the science of nature–nurture), or with entire extended families (see Plomin, DeFries, Knopik, & Neiderhiser, 2012, for a complete introduction to research methods relevant to nature–nurture).

For better or for worse, contentions about nature–nurture have intensified because quantitative genetics produces a number called a heritability coefficient, varying from 0 to 1, that is meant to provide a single measure of genetics’ influence of a trait. In a general way, a heritability coefficient measures how strongly differences among individuals are related to differences among their genes. But beware: Heritability coefficients, although simple to compute, are deceptively difficult to interpret. Nevertheless, numbers that provide simple answers to complicated questions tend to have a strong influence on the human imagination, and a great deal of time has been spent discussing whether the heritability of intelligence or personality or depression is equal to one number or another.

One reason nature–nurture continues to fascinate us so much is that we live in an era of great scientific discovery in genetics, comparable to the times of Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton, with regard to astronomy and physics. Every day, it seems, new discoveries are made, new possibilities proposed. When Francis Galton first started thinking about nature–nurture in the late-19th century he was very influenced by his cousin, Charles Darwin, but genetics per se was unknown. Mendel’s famous work with peas, conducted at about the same time, went undiscovered for 20 years; quantitative genetics was developed in the 1920s; DNA was discovered by Watson and Crick in the 1950s; the human genome was completely sequenced at the turn of the 21st century; and we are now on the verge of being able to obtain the specific DNA sequence of anyone at a relatively low cost. No one knows what this new genetic knowledge will mean for the study of nature–nurture, but as we will see in the next section, answers to nature–nurture questions have turned out to be far more difficult and mysterious than anyone imagined.

What Have We Learned About Nature–Nurture?

It would be satisfying to be able to say that nature–nurture studies have given us conclusive and complete evidence about where traits come from, with some traits clearly resulting from genetics and others almost entirely from environmental factors, such as childrearing practices and personal will; but that is not the case. Instead, everything has turned out to have some footing in genetics. The more genetically-related people are, the more similar they are—for everything: height, weight, intelligence, personality, mental illness, etc. Sure, it seems like common sense that some traits have a genetic bias. For example, adopted children resemble their biological parents even if they have never met them, and identical twins are more similar to each other than are fraternal twins. And while certain psychological traits, such as personality or mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia), seem reasonably influenced by genetics, it turns out that the same is true for political attitudes, how much television people watch (Plomin, Corley, DeFries, & Fulker, 1990), and whether or not they get divorced (McGue & Lykken, 1992).

It may seem surprising, but genetic influence on behavior is a relatively recent discovery. In the middle of the 20th century, psychology was dominated by the doctrine of behaviorism, which held that behavior could only be explained in terms of environmental factors. Psychiatry concentrated on psychoanalysis, which probed for roots of behavior in individuals’ early life-histories. The truth is, neither behaviorism nor psychoanalysis is incompatible with genetic influences on behavior, and neither Freud nor Skinner was naive about the importance of organic processes in behavior. Nevertheless, in their day it was widely thought that children’s personalities were shaped entirely by imitating their parents’ behavior, and that schizophrenia was caused by certain kinds of “pathological mothering.” Whatever the outcome of our broader discussion of nature–nurture, the basic fact that the best predictors of an adopted child’s personality or mental health are found in the biological parents he or she has never met, rather than in the adoptive parents who raised him or her, presents a significant challenge to purely environmental explanations of personality or psychopathology. The message is clear: You can’t leave genes out of the equation. But keep in mind, no behavioral traits are completely inherited, so you can’t leave the environment out altogether, either.

Trying to untangle the various ways nature-nurture influences human behavior can be messy, and often common-sense notions can get in the way of good science. One very significant contribution of behavioral genetics that has changed psychology for good can be very helpful to keep in mind: When your subjects are biologically-related, no matter how clearly a situation may seem to point to environmental influence, it is never safe to interpret a behavior as wholly the result of nurture without further evidence. For example, when presented with data showing that children whose mothers read to them often are likely to have better reading scores in third grade, it is tempting to conclude that reading to your kids out loud is important to success in school; this may well be true, but the study as described is inconclusive, because there are genetic as well asenvironmental pathways between the parenting practices of mothers and the abilities of their children. This is a case where “correlation does not imply causation,” as they say. To establish that reading aloud causes success, a scientist can either study the problem in adoptive families (in which the genetic pathway is absent) or by finding a way to randomly assign children to oral reading conditions.

The outcomes of nature–nurture studies have fallen short of our expectations (of establishing clear-cut bases for traits) in many ways. The most disappointing outcome has been the inability to organize traits from more– to less-genetic. As noted earlier, everything has turned out to be at least somewhat heritable (passed down), yet nothing has turned out to be absolutely heritable, and there hasn’t been much consistency as to which traits are moreheritable and which are less heritable once other considerations (such as how accurately the trait can be measured) are taken into account (Turkheimer, 2000). The problem is conceptual: The heritability coefficient, and, in fact, the whole quantitative structure that underlies it, does not match up with our nature–nurture intuitions. We want to know how “important” the roles of genes and environment are to the development of a trait, but in focusing on “important” maybe we’re emphasizing the wrong thing. First of all, genes and environment are both crucial to every trait; without genes the environment would have nothing to work on, and too, genes cannot develop in a vacuum. Even more important, because nature–nurture questions look at the differences among people, the cause of a given trait depends not only on the trait itself, but also on the differences in that trait between members of the group being studied.

The classic example of the heritability coefficient defying intuition is the trait of having two arms. No one would argue against the development of arms being a biological, genetic process. But fraternal twins are just as similar for “two-armedness” as identical twins, resulting in a heritability coefficient of zero for the trait of having two arms. Normally, according to the heritability model, this result (coefficient of zero) would suggest all nurture, no nature, but we know that’s not the case. The reason this result is not a tip-off that arm development is less genetic than we imagine is because people do not vary in the genes related to arm development—which essentially upends the heritability formula. In fact, in this instance, the opposite is likely true: the extent that people differ in arm number is likely the result of accidents and, therefore, environmental. For reasons like these, we always have to be very careful when asking nature–nurture questions, especially when we try to express the answer in terms of a single number. The heritability of a trait is not simply a property of that trait, but a property of the trait in a particular context of relevant genes and environmental factors.

Another issue with the heritability coefficient is that it divides traits’ determinants into two portions—genes and environment—which are then calculated together for the total variability. This is a little like asking how much of the experience of a symphony comes from the horns and how much from the strings; the ways instruments or genes integrate is more complex than that. It turns out to be the case that, for many traits, genetic differences affect behavior under some environmental circumstances but not others—a phenomenon called gene-environment interaction, or G x E. In one well-known example, Caspi et al. (2002) showed that among maltreated children, those who carried a particular allele of the MAOA gene showed a predisposition to violence and antisocial behavior, while those with other alleles did not. Whereas, in children who had not been maltreated, the gene had no effect. Making matters even more complicated are very recent studies of what is known as epigenetics (see module, “Epigenetics”), a process in which the DNA itself is modified by environmental events, and those genetic changes transmitted to children.

Some common questions about nature–nurture are, how susceptible is a trait to change, how malleable is it, and do we “have a choice” about it? These questions are much more complex than they may seem at first glance. For example, phenylketonuria is an inborn error of metabolism caused by a single gene; it prevents the body from metabolizing phenylalanine. Untreated, it causes intellectual disability and death. But it can be treated effectively by a straightforward environmental intervention: avoiding foods containing phenylalanine. Height seems like a trait firmly rooted in our nature and unchangeable, but the average height of many populations in Asia and Europe has increased significantly in the past 100 years, due to changes in diet and the alleviation of poverty. Even the most modern genetics has not provided definitive answers to nature–nurture questions. When it was first becoming possible to measure the DNA sequences of individual people, it was widely thought that we would quickly progress to finding the specific genes that account for behavioral characteristics, but that hasn’t happened. There are a few rare genes that have been found to have significant (almost always negative) effects, such as the single gene that causes Huntington’s disease, or the Apolipoprotein gene that causes early onset dementia in a small percentage of Alzheimer’s cases. Aside from these rare genes of great effect, however, the genetic impact on behavior is broken up over many genes, each with very small effects. For most behavioral traits, the effects are so small and distributed across so many genes that we have not been able to catalog them in a meaningful way. In fact, the same is true of environmental effects. We know that extreme environmental hardship causes catastrophic effects for many behavioral outcomes, but fortunately extreme environmental hardship is very rare. Within the normal range of environmental events, those responsible for differences (e.g., why some children in a suburban third-grade classroom perform better than others) are much more difficult to grasp.

The difficulties with finding clear-cut solutions to nature–nurture problems bring us back to the other great questions about our relationship with the natural world: the mind-body problem and free will. Investigations into what we mean when we say we are aware of something reveal that consciousness is not simply the product of a particular area of the brain, nor does choice turn out to be an orderly activity that we can apply to some behaviors but not others. So it is with nature and nurture: What at first may seem to be a straightforward matter, able to be indexed with a single number, becomes more and more complicated the closer we look. The many questions we can ask about the intersection among genes, environments, and human traits—how sensitive are traits to environmental change, and how common are those influential environments; are parents or culture more relevant; how sensitive are traits to differences in genes, and how much do the relevant genes vary in a particular population; does the trait involve a single gene or a great many genes; is the trait more easily described in genetic or more-complex behavioral terms?—may have different answers, and the answer to one tells us little about the answers to the others.

It is tempting to predict that the more we understand the wide-ranging effects of genetic differences on all human characteristics—especially behavioral ones—our cultural, ethical, legal, and personal ways of thinking about ourselves will have to undergo profound changes in response. Perhaps criminal proceedings will consider genetic background. Parents, presented with the genetic sequence of their children, will be faced with difficult decisions about reproduction. These hopes or fears are often exaggerated. In some ways, our thinking may need to change—for example, when we consider the meaning behind the fundamental American principle that all men are created equal. Human beings differ, and like all evolved organisms they differ genetically. The Declaration of Independence predates Darwin and Mendel, but it is hard to imagine that Jefferson—whose genius encompassed botany as well as moral philosophy—would have been alarmed to learn about the genetic diversity of organisms. One of the most important things modern genetics has taught us is that almost all human behavior is too complex to be nailed down, even from the most complete genetic information, unless we’re looking at identical twins. The science of nature and nurture has demonstrated that genetic differences among people are vital to human moral equality, freedom, and self-determination, not opposed to them. As Mordecai Kaplan said about the role of the past in Jewish theology, genetics gets a vote, not a veto, in the determination of human behavior. We should indulge our fascination with nature–nurture while resisting the temptation to oversimplify it.

Check Your Knowledge

To help you with your studying, we’ve included some practice questions for this module. These questions do not necessarily address all content in this module. They are intended as practice, and you are responsible for all of the content in this module even if there is no associated practice question. To promote deeper engagement with the material, we encourage you to create some questions of your own for your practice. You can then also return to these self-generated questions later in the course to test yourself.

Vocabulary

Adoption study

A behavior genetic research method that involves comparison of adopted children to their adoptive and biological parents.

Behavioral genetics

The empirical science of how genes and environments combine to generate behavior.

Heritability coefficient

An easily misinterpreted statistical construct that purports to measure the role of genetics in the explanation of differences among individuals.

Quantitative genetics

Scientific and mathematical methods for inferring genetic and environmental processes based on the degree of genetic and environmental similarity among organisms.

Twin studies

A behavior genetic research method that involves comparison of the similarity of identical (monozygotic; MZ) and fraternal (dizygotic; DZ) twins.

References

- Bouchard, T. J., Lykken, D. T., McGue, M., & Segal, N. L. (1990). Sources of human psychological differences: The Minnesota study of twins reared apart. Science, 250(4978), 223–228.

- Caspi, A., McClay, J., Moffitt, T. E., Mill, J., Martin, J., Craig, I. W., Taylor, A. & Poulton, R. (2002). Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science, 297(5582), 851–854.

- McGue, M., & Lykken, D. T. (1992). Genetic influence on risk of divorce. Psychological Science, 3(6), 368–373.

- Plomin, R., Corley, R., DeFries, J. C., & Fulker, D. W. (1990). Individual differences in television viewing in early childhood: Nature as well as nurture. Psychological Science, 1(6), 371–377.

- Plomin, R., DeFries, J. C., Knopik, V. S., & Neiderhiser, J. M. (2012). Behavioral genetics. New York, NY: Worth Publishers.

- Scott, J. P., & Fuller, J. L. (1998). Genetics and the social behavior of the dog. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Turkheimer, E. (2000). Three laws of behavior genetics and what they mean. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9(5), 160–164.

How to cite this Chapter using APA Style:

Turkheimer, E. (2019). The nature-nurture question. Adapted for use by Queen’s University. Original chapter in R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/tvz92edh

Copyright and Acknowledgment:

This material is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.en_US.

This material is attributed to the Diener Education Fund (copyright © 2018) and can be accessed via this link: http://noba.to/tvz92edh.

Additional information about the Diener Education Fund (DEF) can be accessed here.

By Jeremy G. Stewart & Melissa Milanovic

This is a chapter that you've encountered already in this course. As we shift into content related to self-care, wellness, and psychopathology, and during this busy time of the academic year, we want to revisit this content with you.

Overview

Principles of Psychology (PSYC100) at Queen’s University is a course where we regularly hear that: a) students typically really enjoy the course, and b) students find the course challenging. The goal of this module is to provide an overview of some of the challenges of taking PSYC100 at Queen’s University and strategies to overcome them. In this chapter, we first describe what you know from experience: University life, in general, is at once exciting and demanding. The demands of University life provide the backdrop for the particular challenges that we think are most central to Principles of Psychology. We divide these challenges into those that have most to do with the academic content and those involving our emotional experiences while taking the course. We end by describing evidence-based strategies to overcome these academic and emotional challenges. We hope that this information will act as a reference or starting point to set you up for the best possible outcomes in this course.

Learning Objectives

- Describe factors that impact adjustment to post-secondary education, and that predict success.

- Understand that psychology is a broad science that integrates diverse approaches and methodologies that have their roots in other disciplines (e.g., Biology, Mathematics, Philosophy).

- Learn the scope of mental health problems faced by University students (including those enrolled in Principles of Psychology) and how that might affect working with course content.

- Define trigger warnings and describe the existing evidence for why they are not used in Principles of Psychology.

- Understand and use (where appropriate) strategies to overcome the academic challenges that this course may present.

- Understand and use (where appropriate) strategies to overcome the emotional challenges that this course may present.

University Life

Attending university is unquestionably a privilege. For many, their university years are a momentous period wherein their lives are enriched academically, socially, and emotionally. These years are rife with change; many people transition from late adolescence dependent on parents and/or other caregivers to adults entering the workforce to begin their careers. Along with excitement and opportunity, university life also brings a slew of normative demands and stressors. The approaches you take to navigating the academic and emotional challenges of this course, in particular, need to be weighed in the context of adjustment to university life in general.

There is now a large research literature on academic adjustment, defined as one’s ability to adequately cope with the demands of post-secondary education. The concept encompasses much more than doing well in courses; it also includes one’s motivation to learn, satisfaction with University life, and a sense of goals and purpose (e.g., Baker & Siryk, 1986). It also includes non-academic factors, particularly one’s social and emotional adaptation to University.

Not surprisingly, better academic adjustment predicts degree completion and academic achievement (Brady-Amoon & Fuentes, 2011; Gerdes & Mallinckrodt, 1994). That said, if you are in your first year (or even upper years), there are a number of challenges that you may be navigating that can impact your adjustment. These include, but are not limited to:

- Loneliness. This state of mind may be attributed to separation from family, high school and/or hometown friends, and other important people in your life.

- Financial stress. University is expensive and you may be faced with debt, the need to reduce expenses, and/or needing to increase income (e.g., through a part-time job).

- Class format. Many university classes are large (each PSYC100 section has at least 400 students formally enrolled), somewhat impersonal, and have less structure than a typical high school classroom. This format creates many challenges, including opportunities for distraction.

- Freedom. Most students have much more independence in university than they did before. With freedom and flexibility comes the need to regulate key aspects of your life, including sleep, diet, study schedule, and exercise.

- Social opportunities. University involves meeting new people with experiences, beliefs, and passions that may substantially diverge from your own. This opportunity is exciting and leads to forming new peer groups and relationships. At the same time, there is a need to choose whether or not to engage in certain recreation activities, and more broadly, how to balance one’s work life and social life.

- Personal and emotional problems. From a developmental perspective, the years during which many attend undergraduate university programs – between late adolescence and late 20s – are critical for developing personal values, beliefs, and goals, as well as intimate, trusting relationships (e.g., Erikson, 1963). Questioning one’s purpose, self-worth, relationships, etc. is normal. That said, doing so can also contribute to emotional turmoil and personal crises (more on personal and emotional challenges below).

In sum, the challenges of this Introductory Psychology course, or any course you might take, do not occur in a vacuum, but instead exist in the context of the many other demands that university life presents. This point is important to remember. We are not suggesting that PSYC100 is the only challenge in your life (we are sure that is far from true) and we do not believe that the strategies we suggest for navigating the course are “one size fits all”. We hope to shed light on some of the more common barriers, and provide a useful starting point for building a set of individualized skills and strategies.

Challenges in Principles of Psychology

At Queen’s University (and, we suspect, at many other institutions) Principles of Psychology is not a “bird course” (i.e., a course in which it is very easy to get a high grade). In fact, www.birdcourses.com rates the course a “C” for “birdiness” — their scale is the academic letter grade system, with F being the most difficult / least “birdy” course — based on input from students who have taken it in the past decade. Overall, we agree with this assessment – from our perspective, Principles of Psychology is one of the more rewarding and interesting courses offered at Queen’s. However, part of what makes it this way is also why it presents both academic and emotional challenges for students.

Academic Challenges

Psychology is a science. Perhaps the most common source of academic difficulties in Principles of Psychology stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of what psychology is. Many find the degree to which topics like neuroanatomy, endocrinology, reproductive biology, genetics, statistics, and research methods (to name a few!) are emphasized in Principles of Psychology surprising. There is a misconception that knowledge of these topics is only relevant to “hard sciences” like Biology, Chemistry, Physics, Mathematics, etc. While understandable, this view is an unhelpful, false dichotomy that we strive to debunk in this course.

The study of psychology is firmly grounded in empiricism and the scientific method. In order to understand and interpret research in psychology, it is critical to have a firm grasp of research design, hypothesis testing, and statistics. Further, one of the most exciting things about Psychology is that it is multi-disciplinary. Our thoughts and behaviors are complex, and to understand them, scientists must draw on theory and methods from diverse disciplines. One example of drawing on information from diverse fields is the National Institute of Mental Health’s influential Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project. Launched in 2008, the RDoC framework has shaped how scientists study the causes and symptoms of mental illnesses. A core RDoC tenant is that mental illness must be classified and studied at multiple “units of analysis” (e.g., molecules, cells, brain circuits, behaviours). Guided by this comprehensive understanding of mental illness, scientists and clinicians have made breakthroughs in treatment and prevention.

What does all of this mean? The bottom line is that some of the content in Principles of Psychology will overlap (and even extend) material that you may see in courses in Biology, Chemistry, Statistics, Mathematics, and others. For instance, you will learn about the anatomy and physiology of structures involved in sensation and perception, and about the statistical properties of a normal curve. Learning content that overlaps with a range of other disciplines is undoubtedly a tall order for students to tackle, but the variability and multi-disciplinary nature of psychological science is what makes it a fascinating and rewarding area of study.

Psychology is very broad. Related to the point above, Principles of Psychology covers considerable ground in the 24 weeks allotted to lectures and labs. Topics touch on many of the major disciplines in psychology, including Sensation and Perception, Clinical Psychology, Neuroscience, Developmental Psychology, Personality and Social Psychology, Learning/Behavioural Psychology, and Cognitive Psychology. These areas of psychology are in and of themselves very broad (indeed, our department devotes several upper year courses to each) and include multiple sub-disciplines. The course also touches on the history of psychology, research methods, and statistics. So, a lot to accomplish in a short period of time!

One challenging aspect is learning and mastering a lot of information. The diversity of topics covered makes this learning tricky, as you might feel as though you are “shifting gears” frequently, rather than cruising seamlessly from one content area to the next. This challenge makes students more flexible, efficient, and altogether better learners, and this is one of the benefits of studying psychology. So the potential added layer of difficulty in the short-term is worthwhile in the long term! Second, lectures, readings, learning labs, and quizzes will emphasize common threads or connections among course topics. We have made an effort to have content build on itself wherever possible, andto demonstrate how very diverse areas of psychology share common basic principles and themes.

Multiple Methods of Learning. Especially in the blended version of Principles of Psychology (students attend lecture), the material is presented and learned in several formats. Relative to traditional models, this instructional approach improves performance and attendance, partly because students prefer blended courses to traditional courses (Stockwell et al., 2015). However, active engagement with course material (e.g., preparing for and participating in learning labs; completing quizzes; preparing for lecture by reviewing and annotating textbook readings) takes time. It also is harder than passively absorbing content by simply “showing up” for weekly lectures and labs. Making full use of the different ways of learning offered in Principles of Psychology may mean prioritizing them regularly from week-to-week.

Fully benefitting from the richness Principles of Psychology demands organization, scheduling, and planning ahead. University life is busy and presents opportunities and challenges that you will be juggling while enrolled in this course. AndPrinciples of Psychology is only one of the courses in which you are enrolled! Thus, in many ways, this course (and most others) asks you to reflect on what’s important to you and purposefully adjust your behavior so that it is in line with your priorities and goals. This reflection takes self-knowledge and maturity; it’s disarmingly difficult at times to act in a value-consistent manner. In fact, some psychotherapies aim to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety in part by helping patients identify values and change behaviour in accordance with them (e.g., Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2011). Structuring your time (see “Strategies to Overcome Academic Challenges” below) is a great place to start. If nothing else, it can make a proverbial mountain look more like a molehill, and is a good way to set yourself up for success in this course.

Emotional Challenges

Principles of Psychology may be more emotionally taxing than many or all of your other courses. Generally, this response is because much of (but not all) of the content tackles human processes – how we perceive, think, feel, and behave. In short, the course content can be highly relatable, and you may make connections with what you’ve learned about yourself, your loved ones, and/or other important people in your life. In our experience, this relatability interacts with what students bring into the course. We can all probably think about significant hardships we’ve endured and moments in our lives that have tested us to our limits; we all bring our unique emotional histories. Here, we focus briefly on what we know about the mental health of university students and aspects of the course content that may be especially challenging for those with lived experience with mental illness.

University Mental Health. In late 2014, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) World Mental Health International College Student (WMH-ICS) surveys were launched. The initial round of surveys were completed by over 14,000 first-year university students across 19 institutions in 8 countries. The scope and rigor of these surveys has already provided unparalleled insight into the mental health of university students and the impact mental illness has on adjustment and functioning.

The results are sobering. More than 1 in 3 (35.3%) of first year students reported at least one diagnosable mental illness (according to the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders [4th ed.]; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) in their lifetimes. Among these, the most common were Major Depressive Disorder (21.2%) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (18.6%), mental illnesses characterized by low mood and/or a lack of pleasure and persistent, frequent anxiety, respectively. Although less common, alcohol and substance use disorders affected more than 1 in 5 students (Auerbach et al., 2018). Critically, more than 80% of these mental illnesses began prior to the start of university, and fewer than 1 in 5 students with at least one mental illness reported receiving even minimally adequate treatment in the year prior to being surveyed. Perhaps consequently, pre-matriculation mental illnesses are related to University attrition (Auerbach et al., 2016).

The WMH-ICS surveys also have shed light on how common suicidal thoughts and behaviors may be among incoming students. In their lifetimes, nearly one-third (32.7%) of students reported seriously thinking of killing themselves on purpose (i.e., suicidal ideation) while 17.5% (more than 1 in 6) reported having made a plan to die by suicide (e.g., what method they would use and where they would do it). Finally, before starting University, more than 1 in 25 students (4.3%) reported having done something to purposefully injure themselves with some intent to die by their own hands (i.e., a suicide attempt) (Mortier et al., 2018). Further, an additional 4.8% to 6.4% of students experienced first onsets of suicidal thoughts or behaviours during university annually (Mortier et al., 2016). That means that each year, we would expect approximately 1 in 5 students who had never experienced suicidal thoughts and behaviours in their lives to first report them in any given university year.

These are alarming statistics. It may not be surprising that the presence of mental illness(es) and/or suicidal thoughts and behaviours are associated with poorer academic performance (Bruffaerts et al., 2018; Mortier et al., 2015) and not completing one’s program of study (Auerbach et al., 2016). However, mental illness and suicide can impact our lives in indirect ways, even if we are not personally coping with these. Given how widespread these problems are, if we ourselves are not experiencing symptoms related to mental illness and/or suicidal thoughts and behaviours, someone we love and are very close to—a parent, sibling, partner, friend—certainly is.

There are two take-home points from this discussion. First, mental health problems are common. If you are coping with them, you certainly aren’t alone. Research suggests that mental illness reduces student academic success and adjustment in university overall, but very few people receive the treatment that might help. Accessing personal support systems and professional help will increase your ability to navigate university life (see strategies below as well). Second, your lived experiences with symptoms related to mental illness will provide a unique lens through which to view the material; it may also leave you open to strong and/or unexpected reactions to aspects of the course content. It’s impossible to predict what may be most jarring; nonetheless, below we turn to some notable parts of the course content that may be most emotionally challenging.

Course content. As much of the content of Principles of Psychology concerns the study of us – what we think and feel, how we act, and what we experience – parts of the material may resonate with you deeply. Indeed, we hope this is the case! The potential downside is you may come across content that you find challenging or activating.

Given the prevalence of mental illness and suicide in the general population, an obvious area in which you may face some tough course content is the Clinical Psychology section. This section will: give a broad overview of the history of mental illness; cover the symptoms, course, and causes of several psychiatric conditions; and discuss available treatments. Hearing about the specific symptoms of mental illnesses and the impacts these can have on people’s lives can remind us of our own personal experiences and/or what our loved ones have been through. In general, hearing about precursors to psychiatric symptoms – for example, child abuse, major traumatic events (e.g., being the victim of violence), and substance use – can be upsetting. Hearing about the hardships people face and the fundamental inequalities that can bring on and perpetuate mental illness can be moving. A challenge of this course, and this section in particular, is noticing how these things impact us, taking care of ourselves as needed, and using our experiences as fuel for our scholarship. These challenges are tricky to accomplish, and we provide some strategies that could prove helpful below.

The emotional challenges of the course content do not end necessarily with the Clinical Psychology section. For example, a major topic in Social Psychology concerns how people create “in groups” (others with whom one feels they have a lot in common) and “out groups” (others who share few of one’s broad characteristics and/or belies). Creating these dichotomies has an important evolutionary and interpersonal function. Nonetheless, our tendency to think in terms of “in groups” and “out groups” can contribute to stereotypes, bigotry, and hatred. Many of us and particularly those with lived experience of discrimination may find this difficult to discuss and learn about. As another example, a large and vibrant area of research in Developmental Psychology concerns how children form caring relationships with their parents, and how those relationships are fostered (or thwarted) by parenting practices over time. Learning about attachment styles (e.g., Bowlby, 1969) can be quite provocative depending on your experiences with being cared for and parented when you were young.

The key take away is that, more than many other courses, the content within Principles of Psychology may trigger strong feelings and reactions. We think that the strong emotions psychology may generate is a strength of psychology and something that can make it intrinsically fascinating. We also think that the potential for content to be provocative is something to keep in the back of your mind and watch in a very purposeful way (see more below).

Strategies for Successfully Navigating this Course

Strategies to Overcome Academic Challenges

The change from a high school to university course load can feel dramatic. Suddenly there are extensive readings to complete each week, assignments to stay on top of, and examinations to prepare for, across multiple courses. It can be easy to become overwhelmed with the amount of academic material to manage. The following are some strategies to help manage your academic demands to help facilitate your ability to manage your time effectively.

Scheduling your time. It is very helpful to get into the habit of creating a weekly schedule. This scheduling not only helps you to sort out what work you plan to focus on each week, and when, but also ensures you are scheduling balanced activities into your life outside of your academics. Having a schedule can lead you to be more productive with your time and manage feelings of being overwhelmed by all of the things you need to do each week.

The Student Academic Success Services at Queen’s University provides a helpful technique for generating a weekly schedule (http://sass.queensu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Weekly-Schedule-Template-2019.docx.pdf) that helps you to make sure you are scheduling your time to include all of your fixed commitments (such as classes, appointments, and team meetings), health habits (such as eating, sleeping, exercise and relaxing), time for homework and everything else (including grocery shopping, laundry, and socializing).

Keeping focused. Do you get easily distracted? Perhaps when you sit down to do some work, your mind wanders to all the other things you need to do, such as “will I remember to text my friend later to hang out?” or “I have to remember to do that online quiz before tomorrow night”. Using a distraction pad to write down wandering thoughts and to-do items while you are working can help you to make sure you are not forgetting anything important, by writing them down for later. This practice also keeps you from getting distracted by going to do the task that has popped into your mind while working on something else.

Getting distracting thoughts out of your head by writing them down on paper can help you focus on the task at hand. You can then set a specific time each evening to review your distraction pad, at which time you can decide which items are insignificant and can be forgotten, and which items are important. You can then turn the important items into specific actions, and plan for when you will tackle them by slotting them into your weekly schedule.

Not only can your thoughts distract you from attending to your work, but electronic devices also can be very distracting. It is important that each time you sit down to complete a session of work, you decide if you need your digital device in order to do it. If you do not need it, consider leaving your phone or computer in another room, or at home if you plan to work somewhere outside of your home. If you do need your device, consider blocking unnecessary sites with digital applications, or schedule short breaks (e.g., 5-10 minutes) approximately every hour to check for notifications on social media. Of course, everyone’s attention span is different, so it is important that you find the limits of your attention for a particular task. Once you have figured out how long you can focus for on the particular activity or subject, you can break down your tasks into goals or chunks of work that you anticipate will take that long to complete.

Effective Studying. Finding a place to work. Where do you study most often? When you are sitting down to do your school work, consider your environment. Are you someone who needs a quiet space, or do you prefer to be around people and music? How distracted do you get by your phone and computer? Reflect on what the ideal work environment is for you, and plan to find a space that is most conducive to your own ability to focus when planning to do your coursework. You may not know what works best for you yet, and that is okay! Try out a few spaces (e.g., residence room, coffee shop, library cubicle, study rooms on campus) before making your decision.

Setting yourself up for success. Before you start a session of work, set a goal for yourself. For example, I would like to read this week’s chapter for Psych 100 in the next 50 minutes. Set a time commitment to your goal, minimize distractions, and be sure to schedule yourself a break so that you can rest your mind before moving on to the next task.

The skills discussed so far take practice to develop, and they may be new skills for you. Now is a great time to connect with people who are trained to teach and develop good study habits. At Queen’s University, we have an entire team dedicated to helping students learn how to learn. The team is called Student Academic Success Services, or SASS for short. SASS has a number of learning and writing resources to assist you with your academics, including free 1-on-1 appointments with learning strategists for Queen’s students (https://sass.queensu.ca/).

Strategies to Overcome Emotional Challenges

Forewarned is forearmed. Among the emotional challenges of Principles of Psychology is encountering material that could be upsetting to you. Upsetting content could be something you read in your textbook, read or watch online, or hear in lecture. Oftentimes course content that is most likely to affect us connects with some important experiences we have had, or that have happened to people we love, or both.

A deceptively simple strategy for addressing the emotional challenges of this course is looking well ahead in your syllabus. Doing so might allow you to identify, well in advance, topics that you might find difficult to learn and/or read about because of personal experiences. This approach would give you time to find out more about the content by asking your teaching assistants, instructors, or course coordinators (e.g., Undergraduate Chair in Psychology). Knowing what’s coming might allow you to prepare for certain topics. For instance, you might decide to review and practice some recommended coping skills (described below) and/or recruit a friend, partner, or other source of support to attend a lecture with you. Further, you might schedule activities that you find fun or distracting on days you know you will be encountering content you are likely to find distressing.

Although you may come across them in other courses, Principles of Psychology does not give trigger warnings for any course content. The reasons are both scientific and pedagogical. From a scientific standpoint, studies that have investigated the effects of trigger warnings are mixed, but the bottom line is they either have no impact or a slightly negative impact on overall student well-being. On the pedagogical side, the use of trigger warnings may lead to the avoidance of course material which impedes learning this material. Beyond course material, a more important learning opportunity also may be missed. Since trigger warnings may encourage avoidance of things that are upsetting, there are no opportunities to experience potential “triggers” and learn that you can cope, that the threat is not as bad as you thought, or that the intense emotional reaction you have does not last forever. Indeed, this principle of exposure to things that may be triggering or upsetting is a cornerstone of psychological treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety disorders (e.g., Abramowitz, Deacon, & Whiteside, 2019; Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 2007). Further, avoidance is a key mechanism that drives the persistence and worsening of many mental health symptoms (e.g., Ottenbreit, Dobson, & Quigley, 2014). For the interested reader, Box 1 presents more information about trigger warnings and further rationale for why these are not used in Principles of Psychology.

Trigger Warnings

Trigger warnings are advance notifications at the start of a video, piece of writing, or, in educational contexts, a lecture or topic, that contains potentially distressing material. Trigger warnings involve a description of the potentially distressing content with the goal of providing the opportunity to prepare for or avoid this content. On the surface, if trigger warnings help people cope with challenging information, this might reduce negative reactions and ultimately protect mental health.

Our primary reason for not using trigger warnings is the lack of scientific evidence that they do what they are supposed to. If trigger warnings protected students from discomfort or distress, using them might have benefits that outweigh their psychological costs (see below). For instance, in a series of carefully designed experiments, Bridgland and colleagues (2019) gave some participants trigger warnings about a graphic photo and measured their levels of negative affect (e.g., adjectives like “distressed”) and anxiety before and after viewing the photo. Another group of participants did not receive any warning. In five separate studies, the groups (warned and unwarned) did not differ in their emotional reactions to graphic, upsetting content. This general effect – that trigger warnings do not impact emotional reactions to potentially upsetting content – has been replicated in studies using a graphic written passage (Bellet, Jones, & McNally, 2018) and videos (Sanson, Strange, & Garry, 2019). Sanson and colleagues (2019) summarize their series of six well designed studies as follows: “people who saw trigger warnings, compared to people who did not, judged material to be similarly negative, experienced similarly frequent intrusive thoughts and avoidance, and comprehended subsequent material similarly well.” Ultimately, trigger warnings are not helping to reduce or offset the things that they are supposed to (e.g., distress, intrusive memories), which raises questions about their appropriateness for educational contexts.

You may be thinking that, even if they are not overtly helpful, trigger warnings can’t hurt, so why not use them? Although “hurt” may be an exaggeration, there is emerging evidence that trigger warnings may have unintended negative consequences. The initial impetus for trigger warnings came out of clinical research on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Briefly, some people with PTSD experience intense recollections (e.g., flashbacks; sensory experiences) of a traumatic event that are triggered by reminders of the trauma. Thus, it was thought warnings of these types of triggers might be helpful. However, critics of trigger warnings have long maintained that trigger warnings encourage avoidance (which fuels the persistence of symptoms and impedes learning coping strategies necessary for treatment) and increase the salience of trauma to an individual’s identity. The result is that PTSD symptoms worsen over time and people do not recover (McNally, 2014, 2016; Rosenthal et al., 2005). In line with these criticisms, studies have uncovered some of the negative side effects of trigger warnings. First, compared to the unwarned, those who receive trigger warnings report greater negative affect and anxiety before viewing the potentially distressing content (Bellet et al., 2018; Bridgland et al., 2019; Gainsburg & Earl, 2018). Second, people who receive trigger warnings avoid the content more (Bridgland et al., 2019; Gainsburg & Earl, 2018); in the context of a University course, this translates to missed learning opportunities in the absence of documented benefits. Finally, trigger warnings may affect people’s beliefs about their own resilience versus vulnerability. In one study, compared to unwarned participants, people who viewed trigger warnings rated themselves, and people in general, as more emotionally vulnerable following traumatic events (Bellet et al., 2018).

In balance, we think trigger warnings likely do very little to make tough content easier to consume. Further, we are concerned about the potential unintended side effects of such warnings. For those reasons, trigger warnings are not used in Principles of Psychology.

If not trigger warnings, then what?

There are ways to cope with potentially upsetting content that do not involve trigger warnings. Strategies that we recommend including:

- Looking ahead at the syllabus

- Reading keywords at the end of each chapter to see if content may be difficult

- Connecting with a member of the instructional team if there is a specific area you are concerned about

If you know you will encounter information that may be distressing, some strategies for engaging with that content include:

- Bringing a friend or family member to lecture on a day where content may be difficult

- Planning light and fun activities following what may be a difficult lecture

- Using coping and relaxation techniques, described below

Coping and Mental Hygiene. Coping means dedicating time and conscious effort to the management of your stress levels and problems that you are faced with. Stress can surface as a result of many factors, including homework, exams, work, volunteer positions, extracurricular activities, and problems in family and peer relations. When we are coping, we are utilizing techniques and engaging in activities that will help us minimize the effects of these stressors on our wellbeing.

A significant part of coping is recognizing the importance of mental hygiene. You are likely familiar with the term hygiene, which refers to practices we engage in that are important for maintaining our health and preventing diseases, such as showering and brushing our teeth. Mental hygiene follows the same general principle, referring to practices we engage in that are important for maintaining our mental health and preventing psychological conditions such as burnout and mental illness.

In this module we will discuss some coping skills that you can use to facilitate mental hygiene and manage your own wellness.

Self-care. You have likely heard of the term self-care. What does it mean to you?

True self-care is not salt baths and chocolate cake, it is making the choice to build a life you don’t need to regularly escape from – Brianna Wiest

Self-care tends to get a reputation in society and the media as simply being the act of taking a bubble bath or eating chocolate to reward oneself. However, self-care is actually multi-faceted, consisting of all of the activities needed to promote and maintain your health, across multiple domains. It is about developing for yourself a life that you feel you can manage, enjoy, and not need to escape from. Self-care activities are not just physical activities, but also mental, emotional, and spiritual. These activities include nutrition, sleep, hygiene, exercise, time with family and friends, as well as time alone and leisure. To engage in self-care is to deliberately choose activities that are nourishing, restorative, and that strengthen your connections with others.

One of the things that makes self-care tricky is that there are many different areas. If you’re spending all your time and energy on your physical health and school, you may find you’re not getting enough social time! Similarly, if you are staying up really late every night of the week to spend time with friends, the exhaustion is going to catch up with you. An important part of engaging in self-care is finding what activities are restorative for you and being sure to schedule them into your week so that your schedule is well-balanced.

Our culture tends to reward people who deal with their stress by working harder and faster to produce more in a shorter time. You might feel compelled to do this, by engaging in cramming sessions to pump out work, and cutting out healthy habits in favour of freeing up more time to focus on studies. However, this behaviour can have a negative effect on your physical and mental health, which can result in burnout, which is a state of physical, mental and emotional collapse caused by overwork or stress.

Our bodies are equipped with something called the fight or flight system, which is activated when we are under stress. This response consists of a series of biochemical changes that prepare our bodies to deal with threat or danger. Primitive people needed rapid bursts in energy to fight or flee from predators such as saber-toothed tigers. This response can help us in threatening situations today, such as having to respond quickly to a car that cuts you off on the highway. However, not only can this system become activated when we are faced with serious dangers in our environment, but it also can activate when we are under a great deal of stress and feeling overwhelmed. Luckily, our bodies are also equipped with a relaxation response which can counter the activation of our fight/flight response.

Take a moment to consider how you relax. Some people enjoy down time, for example, reading an enjoyable book. Others might prefer scheduling time with friends, perhaps going out to dinner or seeing a movie. Some people relax through exercise or yoga. We are all different and what helps one person to relax won’t necessarily be what best helps another. It is important to find out what relaxing activities help you to unwind, and to be sure to make time for these activities throughout the week to help maintain mental wellness.

The following are some techniques you can try out, which can help you to manage your stress levels and overcome emotional challenges. These techniques are drawn from evidence-based therapy protocols (e.g., Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Beck, 1979, Beck, 2011; Dialectical Behaviour Therapy, Linehan, 2015; Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2011). These psychological therapies have been extensively researched, and are used to improve individuals’ well-being across multiple mental and physical health problems.

Deep breathing. Breathing is a fundamental necessity of life that we can often take for granted. Certain breathing patterns can contribute to feelings of anxiety, panic attacks, low mood, muscle tension and fatigue. When we’re anxious or stressed out, our breathing tends to become rapid and shallow. In contrast, when we are relaxed, our breathing is much deeper and slower. A technique that can help manage your stress levels, is to engage in deep breathing. This form of breathing has been found to be effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety and improving feelings of relaxation. When you recognize that you are breathing in a quick and shallow way, consciously make the choice to engage in slower breathing for a few minutes. For each breath, focus on inhaling air deep into the lungs through your nose as the abdomen expands. After holding this breath for a few moments, exhale the air out of your mouth, noticing your abdomen contracting. The process of deep breathing signals to your body that it is safe to relax and activates your relaxation response.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation. Maybe you have noticed when you are in a stressful situation or feeling overwhelmed that there is a tightening in your body. Perhaps you feel it in your shoulders, or back, or maybe you get headaches. When we are stressed, we hold tightness in our muscles and this sends signals to our brain that we are stressed out. Not only can this negatively affect how our bodies feel, but it can also influence our mood and our thoughts that we have. A good way to relax our mind, is to deliberately relax our body, taking purposeful steps to relax our muscles. Using the technique of progressive muscle relaxation, you go through each muscle group in your body, one by one, tensing the muscle groups and holding that tension for a several seconds, followed by releasing the tension in the muscle group. This relaxing of our tension sends feedback to our brain that we are feeling calm and relaxed.

Visualization. Have you ever heard people say “go to your happy place”? This saying may be a reference to a technique called visualization. Research (e.g., Rossman, 2000) shows that focusing the imagination in a positive way can result in a state of ease, mood regulation, and can have a relaxing effect (e.g., imagining a place where you feel calm and safe). Some people do this on their own by really imagining what this place looks like, feels like, and smells like. Some people prefer to be guided to a calm place with an audio track.

Grounding. Grounding is a set of simple strategies to help detach from emotional pain, such as sadness, anger, or anxiety. When you are feeling overwhelmed with emotion, it can be helpful to find a way to detach so that you can gain control of your feelings and cope. Grounding focuses on distraction strategies that help you cope with intense emotions and anchor you to the present moment. There are several ways that you can ground yourself, and it can be done any time, any place, and anywhere. When engaging in grounding, you want to focus on the present moment, rather than ruminating about the past or worrying about the future.

Mental Grounding

- - Describe your environment in detail using all of your senses. Describe what you see in the room, hear, taste, and smell. What is the temperature? What objects do you see, and what textures do you feel? For example: I am in the lecture hall. I see three brown walls, one in front and two to either side. I see a professor and she is pacing back and forth. The temperature is cool. I feel the armrests on my chair, and the pen in my hand.

- - Play a categories game with yourself. Try to think of as many “types of animals”, “cars”, “TV shows”, “sports” as you can.

- - Describe an everyday activity in great detail. For example, describing a meal that you cook (e.g., first I boil the water, then I put salt in it, then I pour the pasta noodles in, and while that is cooking I sauté vegetables and add them to tomato sauce)

- - Use humour. Think of something funny, like a joke or a funny clip from a TV show that you enjoyed.

- - Say a coping statement, such as I can handle this, I will be okay, I will get through this.

Physical Grounding

- - Grab tightly the arm rests of your chair

- - Touch objects around you for the tactile sensation, such as writing utensils, your clothing, or items in your pocket.

- - Walk slowly, noticing each footstep that you take and how your foot curves as you bring it down to meet contact with the ground.

- - Eat something and describe the flavour and texture of the bite to yourself as you hold the item of food in your mouth.

Planned exercise. Physical activity, in addition to having significant health benefit, is often recommended for emotional wellbeing as a technique for managing stress levels. Indeed, research has found that college students who exercised at least 3 days per week were less likely to report poor mental health and perceived stress than students who did not (Vankim & Nelson, 2013). Multiple studies indicate that physical activity improves mood and reduces symptoms of anxiety and depression (Rethorst et al., 2009; Rimer et al., 2012; Trivedi et al., 2011; Ross & Hayes, 1988; Stephens, 1988).

The Athletics and Recreation Centre (ARC) at Queen’s University offers a wide array of fitness opportunities to become active throughout the year, from fitness equipment, to swimming, gymnasiums, racquet courts and more (https://rec.gogaelsgo.com/sports/2013/7/26/Fac-Serv_0726133714.aspx)

Cultural, Diversity and Faith-based resources.

Culture influences our experience in many ways and can have a significant impact on our mental health, playing a role in how we relate to others, manage our emotions, and experience and express psychological distress (Roberts & Burleson, 2013). Queen’s University has several resources and spaces for individuals seeking cultural and spiritual connection:

- Queen’s University African and Caribbean Students Association: https://myams.org/portfolio-items/african-and-caribbean-students-association/

Healthy eating. Maintaining a healthy, balanced diet is not only important for physical health, but also emotional and mental health. Negative affect (e.g., anxiety, frustration, sadness, boredom, depression, fatigue, stress) has been related to food consumption in order to distract oneself from, or cope with, it. The foods consumed are often the “comfort foods” with high sugar and fats, that can provide immediate satisfaction and may even manage mood in the short term; however, leading to greater preference for indulgent foods over healthy foods (Gardner et al., 2014). Research also shows that unhealthy dietary patterns are related to poorer mental health in youth (O’Neil et al., 2014). Better overall diet quality and lower intake of simple carbohydrates and processed foods are related to lower depressive symptoms (Jacka et al., 2011; Mikolajczyk, Ansari, & Maxwell, 2009, Christensen & Somers, 1996; Quehl et al., 2017). Canada’s Food Guide 2019 (https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/) is a great resource that provides tips and recipes for maintaining a healthy, balanced diet.

Thirty-nine percent of Canadian post-secondary students experience some degree of food insecurity, which ranges from worry about running out of food and having limited food selection, to missing meals, reducing food intake, or going without food for an entire day or longer due to lack of money for food. Queen’s University provides the Swipe it Forward program, for short-term meal support (https://dining.queensu.ca/swipeitforward/). The Queen’s University Student Government (AMS) offers a confidential and non-judgmental food bank service to members of the university community (https://myams.org/team-details/food-centre/)

Using Resources. If you find something in Principles of Psychology, or any course, to be very distressing (e.g., a discussion of mental health symptoms that you recognize in yourself) seeking help and support is also a very useful part of coping and mental hygiene. The staff (teaching assistants, course coordinator, and instructors) involved in Principles of Psychology can be good points of contact, especially for connecting you with University-based supports and accommodations (where relevant). If you are concerned about your mental health, here are some additional contacts that you might find useful:

Your family doctor

Book an appointment with your doctor. They can offer advice or refer you to other more specific services to get help. If you do not have a family doctor in Kingston or the surrounding area, Queen’s University Student Wellness Services has a team of doctors and other health professionals: (http://queensu.ca/studentwellness/health-services).

University Counselling Service

The Counselling Service at Queen’s University can help you to address personal or emotional problems that may be interfering with having a positive experience at Queen’s and reaching academic and personal success. This service offers a free and confidential service. The Counselling Service is not only for those with a diagnosis. It can be contacted for any reason: (http://queensu.ca/studentwellness/counselling-services)

Additional Counselling Services and Information Sources

Resolve Counselling (previously k3c) in Kingston: https://www.resolvecounselling.org/

Sexual Assault Centre Kingston: http://sackingston.com/

Teens Health (information resource): http://www.teenshealth.org/

Telephone Lines

24-hour crisis line in the Kingston area: 613-544-4229

Kids Help Phone: 1-800-668-6868 (https://kidshelpphone.ca/)

Telephone Aid Line Kingston (TALK) line: 613-544-1771 (http://www.telephoneaidlinekingston.com/)

Good2Talk (specific for post-secondary students): 1-866-925-5454 (https://good2talk.ca/)

IN AN EMERGENCY

If you are experiencing suicidal thoughts and think that you might be unable to keep yourself safe, visit Kingston General Hospital Emergency Department or call 911.

Resources for Relaxation and Coping

BREATHE 2 RELAX - Breathe2Relax includes breathing exercises to help you cope and relax

MINDSHIFT - Mindshift teaches you how to relax and cope with anxiety

VIRTUAL HOPE BOX - Virtual Hope Box helps you with coping, relaxation, distraction, and positive thinking

THINKFULL - ThinkFull teaches you to cope with stress, solve problems, and live well

FLOWY - Flowy is a game that makes breathing fun, which can help with anxiety

Websites and Free Downloads:

- AnxietyBCYouth :http://youth.anxietybc.com/don%E2%80%99t-tell-me-relax

- Audio files for mental vacation: http://youth.anxietybc.com/mental-vacations

- Visualization for confidence-building: http://youth.anxietybc.com/confidence-builders

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation For Management of Anxiety and Stress (Long Version WITH Music): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6053dnI4Rxg&feature=youtu.be

- McGill University Audio Files for Relaxation: https://www.mcgill.ca/counselling/getstarted/relax-meditate

- The benefits of exercising and how to start: http://youth.anxietybc.com/being-active-facts

Resources for Time Management

EVERNOTE - Capture, organize, and share notes from anywhere (computer or phone)

2Do - Task manager that allows you to enter in your thoughts and ideas before you forget

30/30 - A task manager that allows you to set up a list of tasks, and a length of time for each of them. It uses a timer to tell you when to move on to the next task

Websites and Free Downloads

- Remember the milk https://www.rememberthemilk.com/app/#all

An online to-do list and task manager (can be accessed by phone and computer)

- Google Calendar https://calendar.google.com/calendar

Online scheduling system, allows you to set reminders for scheduled events

- Joe’s Goals http://www.joesgoals.com

Online tool to keep track of your goals

- Self-control https://selfcontrolapp.com

Blocks access to distracting websites for a set period of time that you choose – while still allowing you access to the internet (for Macintosh computers)

- Freedom https://freedom.to

Website blocker to improve focus and productivity.

- RescueTime https://www.rescuetime.com

Shows you how you spend your time on your computer and provides tools to help you be more productive.

- The Pomodoro Technique https://cirillocompany.de/pages/pomodoro-technique

Use a timer to keep yourself on track, both for your working sessions and for your breaks

Free online timer at https://tomato-timer.com

Create your own cue cards to help studying

- Dropbox https://www.dropbox.com

Helpful for working on team projects, and keeps all your files in one place that can be accessed from anywhere with internet (computers, phones)

- Student Academic Success Services at Queen’s University http://sass.queensu.ca/

Access time management templates, strategies, and tools

References

Abramowitz, J. S., Deacon, B. J., & Whiteside, S. P. (2019). Exposure therapy for anxiety: Principles and practice. Guilford Publications.