41 Intelligence

Original chapter by Robert Biswas-Diener adapted by the Queen’s University Psychology Department

This Open Access chapter was originally written for the NOBA project. Information on the NOBA project can be found below.

Intelligence is among the oldest and longest studied topics in all of psychology. The development of assessments to measure this concept is at the core of the development of psychological science itself. This module introduces key historical figures, major theories of intelligence, and common assessment strategies related to intelligence. This module will also discuss controversies related to the study of group differences in intelligence.

Learning Objectives

- List at least two common strategies for measuring intelligence.

- Name at least one “type” of intelligence.

- Define intelligence in simple terms.

- Explain the controversy relating to differences in intelligence between groups.

Introduction

Every year hundreds of grade school students converge on Washington, D.C., for the annual Scripps National Spelling Bee. The “bee” is an elite event in which children as young as 8 square off to spell words like “cymotrichous” and “appoggiatura.” Most people who watch the bee think of these kids as being “smart” and you likely agree with this description.

What makes a person intelligent? Is it heredity (two of the 2014 contestants in the bee have siblings who have previously won)(National Spelling Bee, 2014a)? Is it interest (the most frequently listed favorite subject among spelling bee competitors is math)(NSB, 2014b)? In this module we will cover these and other fascinating aspects of intelligence. By the end of the module you should be able to define intelligence and discuss some common strategies for measuring intelligence. In addition, we will tackle the politically thorny issue of whether there are differences in intelligence between groups such as men and women.

Defining and Measuring Intelligence

When you think of “smart people” you likely have an intuitive sense of the qualities that make them intelligent. Maybe you think they have a good memory, or that they can think quickly, or that they simply know a whole lot of information. Indeed, people who exhibit such qualities appear very intelligent. That said, it seems that intelligence must be more than simply knowing facts and being able to remember them. One point in favor of this argument is the idea of animal intelligence. It will come as no surprise to you that a dog, which can learn commands and tricks seems smarter than a snake that cannot. In fact, researchers and lay people generally agree with one another that primates—monkeys and apes (including humans)—are among the most intelligent animals. Apes such as chimpanzees are capable of complex problem solving and sophisticated communication (Kohler, 1924).

Scientists point to the social nature of primates as one evolutionary source of their intelligence. Primates live together in troops or family groups and are, therefore, highly social creatures. As such, primates tend to have brains that are better developed for communication and long term thinking than most other animals. For instance, the complex social environment has led primates to develop deception, altruism, numerical concepts, and “theory of mind” (a sense of the self as a unique individual separate from others in the group; Gallup, 1982; Hauser, MacNeilage & Ware, 1996).[Also see module Theory of Mind]

The question of what constitutes human intelligence is one of the oldest inquiries in psychology. When we talk about intelligence we typically mean intellectual ability. This broadly encompasses the ability to learn, remember and use new information, to solve problems and to adapt to novel situations. An early scholar of intelligence, Charles Spearman, proposed the idea that intelligence was one thing, a “general factor” sometimes known as simply “g.” He based this conclusion on the observation that people who perform well in one intellectual area such as verbal ability also tend to perform well in other areas such as logic and reasoning (Spearman, 1904).

A contemporary of Spearman’s named Francis Galton—himself a cousin of Charles Darwin– was among those who pioneered psychological measurement (Hunt, 2009). For three pence Galton would measure various physical characteristics such as grip strength but also some psychological attributes such as the ability to judge distance or discriminate between colors. This is an example of one of the earliest systematic measures of individual ability. Galton was particularly interested in intelligence, which he thought was heritable in much the same way that height and eye color are. He conceived of several rudimentary methods for assessing whether his hypothesis was true. For example, he carefully tracked the family tree of the top-scoring Cambridge students over the previous 40 years. Although he found specific families disproportionately produced top scholars, intellectual achievement could still be the product of economic status, family culture or other non-genetic factors. Galton was also, possibly, the first to popularize the idea that the heritability of psychological traits could be studied by looking at identical and fraternal twins. Although his methods were crude by modern standards, Galton established intelligence as a variable that could be measured (Hunt, 2009).

The person best known for formally pioneering the measurement of intellectual ability is Alfred Binet. Like Galton, Binet was fascinated by individual differences in intelligence. For instance, he blindfolded chess players and saw that some of them had the ability to continue playing using only their memory to keep the many positions of the pieces in mind (Binet, 1894). Binet was particularly interested in the development of intelligence, a fascination that led him to observe children carefully in the classroom setting.

Along with his colleague Theodore Simon, Binet created a test of children’s intellectual capacity. They created individual test items that should be answerable by children of given ages. For instance, a child who is three should be able to point to her mouth and eyes, a child who is nine should be able to name the months of the year in order, and a twelve year old ought to be able to name sixty words in three minutes. Their assessment became the first “IQ test.”

“IQ” or “intelligence quotient” is a name given to the score of the Binet-Simon test. The score is derived by dividing a child’s mental age (the score from the test) by their chronological age to create an overall quotient. These days, the phrase “IQ” does not apply specifically to the Binet-Simon test and is used to generally denote intelligence or a score on any intelligence test. In the early 1900s the Binet-Simon test was adapted by a Stanford professor named Lewis Terman to create what is, perhaps, the most famous intelligence test in the world, the Stanford-Binet (Terman, 1916). The major advantage of this new test was that it was standardized. Based on a large sample of children Terman was able to plot the scores in a normal distribution, shaped like a “bell curve” (see Fig. 1). To understand a normal distribution think about the height of people. Most people are average in height with relatively fewer being tall or short, and fewer still being extremely tall or extremely short. Terman (1916) laid out intelligence scores in exactly the same way, allowing for easy and reliable categorizations and comparisons between individuals.

Looking at another modern intelligence test—the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS)—can provide clues to a definition of intelligence itself. Motivated by several criticisms of the Stanford-Binet test, psychologist David Wechsler sought to create a superior measure of intelligence. He was critical of the way that the Stanford-Binet relied so heavily on verbal ability and was also suspicious of using a single score to capture all of intelligence. To address these issues Wechsler created a test that tapped a wide range of intellectual abilities. This understanding of intelligence—that it is made up of a pool of specific abilities—is a notable departure from Spearman’s concept of general intelligence. The WAIS assesses people’s ability to remember, compute, understand language, reason well, and process information quickly (Wechsler, 1955).

One interesting by-product of measuring intelligence for so many years is that we can chart changes over time. It might seem strange to you that intelligence can change over the decades but that appears to have happened over the last 80 years we have been measuring this topic. Here’s how we know: IQ tests have an average score of 100. When new waves of people are asked to take older tests they tend to outperform the original sample from years ago on which the test was normed. This gain is known as the “Flynn Effect,” named after James Flynn, the researcher who first identified it (Flynn, 1987). Several hypotheses have been put forth to explain the Flynn Effect including better nutrition (healthier brains!), greater familiarity with testing in general, and more exposure to visual stimuli. Today, there is no perfect agreement among psychological researchers with regards to the causes of increases in average scores on intelligence tests. Perhaps if you choose a career in psychology you will be the one to discover the answer!

Types of Intelligence

David Wechsler’s approach to testing intellectual ability was based on the fundamental idea that there are, in essence, many aspects to intelligence. Other scholars have echoed this idea by going so far as to suggest that there are actually even different types of intelligence. You likely have heard distinctions made between “street smarts” and “book learning.” The former refers to practical wisdom accumulated through experience while the latter indicates formal education. A person high in street smarts might have a superior ability to catch a person in a lie, to persuade others, or to think quickly under pressure. A person high in book learning, by contrast, might have a large vocabulary and be able to remember a large number of references to classic novels. Although psychologists don’t use street smarts or book smarts as professional terms they do believe that intelligence comes in different types.

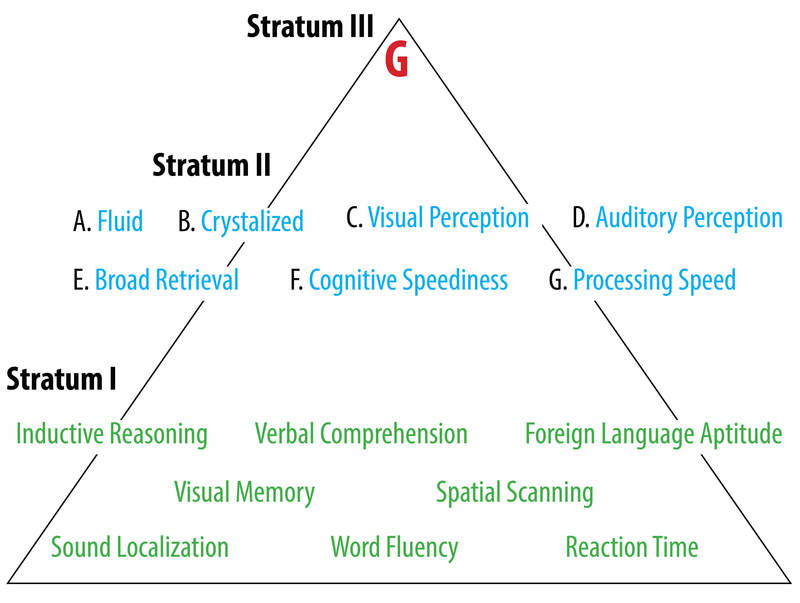

There are many ways to parse apart the concept of intelligence. Many scholars believe that Carroll ‘s (1993) review of more than 400 data sets provides the best currently existing single source for organizing various concepts related to intelligence. Carroll divided intelligence into three levels, or strata, descending from the most abstract down to the most specific (see Fig. 2). To understand this way of categorizing simply think of a “car.” Car is a general word that denotes all types of motorized vehicles. At the more specific level under “car” might be various types of cars such as sedans, sports cars, SUVs, pick-up trucks, station wagons, and so forth. More specific still would be certain models of each such as a Honda Civic or Ferrari Enzo. In the same manner, Carroll called the highest level (stratum III) the general intelligence factor “g.” Under this were more specific stratum II categories such as fluid intelligence and visual perception and processing speed. Each of these, in turn, can be sub-divided into very specific components such as spatial scanning, reaction time, and word fluency.

Thinking of intelligence as Carroll (1993) does, as a collection of specific mental abilities, has helped researchers conceptualize this topic in new ways. For example, Horn and Cattell (1966) distinguish between “fluid” and “crystalized” intelligence, both of which show up on stratum II of Carroll’s model. Fluid intelligence is the ability to “think on your feet;” that is, to solve problems. Crystalized intelligence, on the other hand, is the ability to use language, skills and experience to address problems. The former is associated more with youth while the latter increases with age. You may have noticed the way in which younger people can adapt to new situations and use trial and error to quickly figure out solutions. By contrast, older people tend to rely on their relatively superior store of knowledge to solve problems.

Harvard professor Howard Gardner is another figure in psychology who is well-known for championing the notion that there are different types of intelligence. Gardner’s theory is appropriately, called “multiple intelligences.” Gardner’s theory is based on the idea that people process information through different “channels” and these are relatively independent of one another. He has identified 8 common intelligences including 1) logic-math, 2) visual-spatial, 3) music-rhythm, 4) verbal-linguistic, 5) bodily-kinesthetic, 6) interpersonal, 7) intrapersonal, and 8) naturalistic (Gardner, 1985). Many people are attracted to Gardner’s theory because it suggests that people each learn in unique ways. There are now many Gardner- influenced schools in the world.

Another type of intelligence is Emotional intelligence. Unlike traditional models of intelligence that emphasize cognition (thinking) the idea of emotional intelligence emphasizes the experience and expression of emotion. Some researchers argue that emotional intelligence is a set of skills in which an individual can accurately understand the emotions of others, can identify and label their own emotions, and can use emotions. (Mayer & Salovey, 1997). Other researchers believe that emotional intelligence is a mixture of abilities, such as stress management, and personality, such as a person’s predisposition for certain moods (Bar-On, 2006). Regardless of the specific definition of emotional intelligence, studies have shown a link between this concept and job performance (Lopes, Grewal, Kadis, Gall, & Salovey, 2006). In fact, emotional intelligence is similar to more traditional notions of cognitive intelligence with regards to workplace benefits. Schmidt and Hunter (1998), for example, reviewed research on intelligence in the workplace context and show that intelligence is the single best predictor of doing well in job training programs, of learning on the job. They also report that general intelligence is moderately correlated with all types of jobs but especially with managerial and complex, technical jobs.

There is one last point that is important to bear in mind about intelligence. It turns out that the way an individual thinks about his or her own intelligence is also important because it predicts performance. Researcher Carol Dweck has made a career out of looking at the differences between high IQ children who perform well and those who do not, so-called “under achievers.” Among her most interesting findings is that it is not gender or social class that sets apart the high and low performers. Instead, it is their mindset. The children who believe that their abilities in general—and their intelligence specifically—is a fixed trait tend to underperform. By contrast, kids who believe that intelligence is changeable and evolving tend to handle failure better and perform better (Dweck, 1986). Dweck refers to this as a person’s “mindset” and having a growth mindset appears to be healthier.

Correlates of Intelligence

The research on mindset is interesting but there can also be a temptation to interpret it as suggesting that every human has an unlimited potential for intelligence and that becoming smarter is only a matter of positive thinking. There is some evidence that genetics is an important factor in the intelligence equation. For instance, a number of studies on genetics in adults have yielded the result that intelligence is largely, but not totally, inherited (Bouchard, 2004). Having a healthy attitude about the nature of smarts and working hard can both definitely help intellectual performance but it also helps to have the genetic leaning toward intelligence.

Carol Dweck’s research on the mindset of children also brings one of the most interesting and controversial issues surrounding intelligence research to the fore: group differences. From the very beginning of the study of intelligence researchers have wondered about differences between groups of people such as men and women. With regards to potential differences between the sexes some people have noticed that women are under-represented in certain fields. In 1976, for example, women comprised just 1% of all faculty members in engineering (Ceci, Williams & Barnett, 2009).

Even today women make up between 3% and 15% of all faculty in math-intensive fields at the 50 top universities. This phenomenon could be explained in many ways: it might be the result of inequalities in the educational system, it might be due to differences in socialization wherein young girls are encouraged to develop other interests, it might be the result of that women are—on average—responsible for a larger portion of childcare obligations and therefore make different types of professional decisions, or it might be due to innate differences between these groups, to name just a few possibilities. The possibility of innate differences is the most controversial because many people see it as either the product of or the foundation for sexism. In today’s political landscape it is easy to see that asking certain questions such as “are men smarter than women?” would be inflammatory. In a comprehensive review of research on intellectual abilities and sex Ceci and colleagues (2009) argue against the hypothesis that biological and genetic differences account for much of the sex differences in intellectual ability. Instead, they believe that a complex web of influences ranging from societal expectations to test taking strategies to individual interests account for many of the sex differences found in math and similar intellectual abilities.

A more interesting question, and perhaps a more sensitive one, might be to inquire in which ways men and women might differ in intellectual ability, if at all. That is, researchers should not seek to prove that one group or another is better but might examine the ways that they might differ and offer explanations for any differences that are found. Researchers have investigated sex differences in intellectual ability. In a review of the research literature Halpern (1997) found that women appear, on average, superior to men on measures of fine motor skill, acquired knowledge, reading comprehension, decoding non-verbal expression, and generally have higher grades in school. Men, by contrast, appear, on average, superior to women on measures of fluid reasoning related to math and science, perceptual tasks that involve moving objects, and tasks that require transformations in working memory such as mental rotations of physical spaces. Halpern also notes that men are disproportionately represented on the low end of cognitive functioning including in intellectual disability, dyslexia, and attention deficit disorders (Halpern, 1997).

Other researchers have examined various explanatory hypotheses for why sex differences in intellectual ability occur. Some studies have provided mixed evidence for genetic factors while others point to evidence for social factors (Neisser, et al, 1996; Nisbett, et al., 2012). One interesting phenomenon that has received research scrutiny is the idea of stereotype threat. Stereotype threat is the idea that mental access to a particular stereotype can have real-world impact on a member of the stereotyped group. In one study (Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1999), for example, women who were informed that women tend to fare poorly on math exams just before taking a math test actually performed worse relative to a control group who did not hear the stereotype. One possible antidote to stereotype threat, at least in the case of women, is to make a self-affirmation (such as listing positive personal qualities) before the threat occurs. In one study, for instance, Martens and her colleagues (2006) had women write about personal qualities that they valued before taking a math test. The affirmation largely erased the effect of stereotype by improving math scores for women relative to a control group but similar affirmations had little effect for men (Martens, Johns, Greenberg, & Schimel, 2006).

These types of controversies compel many lay people to wonder if there might be a problem with intelligence measures. It is natural to wonder if they are somehow biased against certain groups. Psychologists typically answer such questions by pointing out that bias in the testing sense of the word is different than how people use the word in everyday speech. Common use of bias denotes a prejudice based on group membership. Scientific bias, on the other hand, is related to the psychometric properties of the test such as validity and reliability. Validity is the idea that an assessment measures what it claims to measure and that it can predict future behaviors or performance. To this end, intelligence tests are not biased because they are fairly accurate measures and predictors. There are, however, real biases, prejudices, and inequalities in the social world that might benefit some advantaged group while hindering some disadvantaged others.

Conclusion

Although you might not be able to spell “esquamulose” or “staphylococci” – indeed, you might not even know what they mean—you don’t need to count yourself out in the intelligence department. Now that we have examined intelligence in depth we can return to our intuitive view of those students who compete in the National Spelling Bee. Are they smart? Certainly, they seem to have high verbal intelligence. There is also the possibility that they benefit from either a genetic boost in intelligence, a supportive social environment, or both. Watching them spell difficult words there is also much we do not know about them. We cannot tell, for instance, how emotionally intelligent they are or how they might use bodily-kinesthetic intelligence. This highlights the fact that intelligence is a complicated issue. Fortunately, psychologists continue to research this fascinating topic and their studies continue to yield new insights.

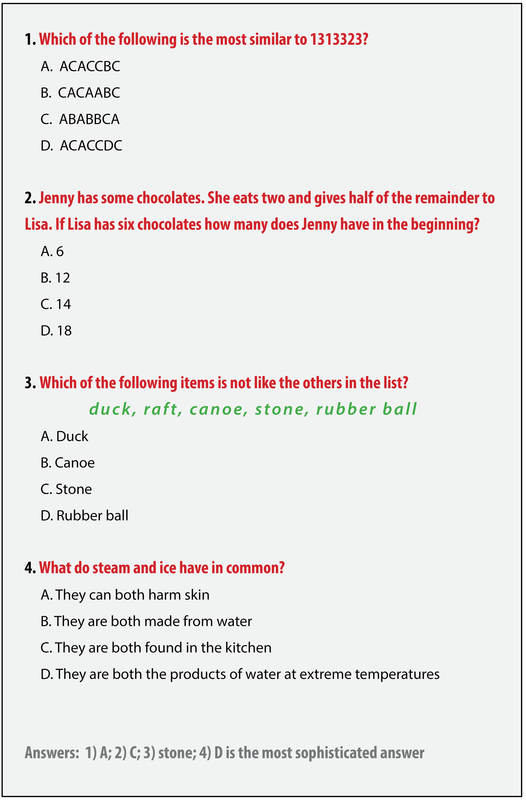

Check Your Knowledge

To help you with your studying, we’ve included some practice questions for this module. These questions do not necessarily address all content in this module. They are intended as practice, and you are responsible for all of the content in this module even if there is no associated practice question. To promote deeper engagement with the material, we encourage you to create some questions of your own for your practice. You can then also return to these self-generated questions later in the course to test yourself.

Vocabulary

- G

- Short for “general factor” and is often used to be synonymous with intelligence itself.

- Intelligence

- An individual’s cognitive capability. This includes the ability to acquire, process, recall and apply information.

- IQ

- Short for “intelligence quotient.” This is a score, typically obtained from a widely used measure of intelligence that is meant to rank a person’s intellectual ability against that of others.

- Norm

- Assessments are given to a representative sample of a population to determine the range of scores for that population. These “norms” are then used to place an individual who takes that assessment on a range of scores in which he or she is compared to the population at large.

- Standardize

- Assessments that are given in the exact same manner to all people . With regards to intelligence tests standardized scores are individual scores that are computed to be referenced against normative scores for a population (see “norm”).

- Stereotype threat

- The phenomenon in which people are concerned that they will conform to a stereotype or that their performance does conform to that stereotype, especially in instances in which the stereotype is brought to their conscious awareness.

References

- Bar-On, R. (2006). The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicometha, 18(Suppl.), 13–25.

- Binet, A. (1894). Psychologie des grands calculateurs et joueurs d’échecs. Paris: Librairie Hachette.

- Bouchard, T.J. (2004). Genetic influence on human psychological traits – A survey. Current Directions in Psychological Science 13(4), 148–151.

- Carroll, J. B. (1993). Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor-analytic studies. Cambridge, England:Cambridge University Press.

- Carroll, J. B. (1993). Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor-analytic studies. Cambridge, England:Cambridge University Press.

- Ceci, S. J., Williams, W. & Barnett, S. M. (2009). Women’s underrepresentation in science: socio cultural and biological considerations. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 218-261.

- Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American psychologist, 41(10), 1040-1048.

- Flynn J. R. (1987). “Massive IQ gains in 14 nations: What IQ tests really measure”. Psychological Bulletin 101, 171–191.

- Gallup, G. G. (1982). Self‐awareness and the emergence of mind in primates. American Journal of Primatology, 2(3), 237-248.

- Gardner, H. (1985). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

- Halpern, D. F. (1997). Sex differences in intelligence: Implications for education. American Psychologist, 52(10), 1091-1102.

- Halpern, D. F. (1997). Sex differences in intelligence: Implications for education. American Psychologist, 52(10), 1091-1102.

- Hauser, M. D., MacNeilage, P., & Ware, M. (1996). Numerical representations in primates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93(4), 1514-1517.

- Horn, J. L., & Cattell, R. B. (1966). Refinement and test of the theory of fluid and crystallized general intelligences. Journal of Educational Psychology, 57(5), 253-270.

- Hunt, M. (2009). The story of psychology. New York: Random House, LLC.

- Hunt, M. (2009). The story of psychology. New York: Random House, LLC.

- Kohler, W. (1924). The mentality of apes. Oxford: Harcourt, Brace.

- Lopes, P. N., Grewal, D., Kadis, J., Gall, M., & Salovey, P. (2006). Evidence that emotional intelligence is related to job performance and affect and attitudes at work. Psicothema, 18(Suppl.), 132–138.

- Martens, A., Johns, M., Greenberg, J., & Schimel, J. (2006). Combating stereotype threat: The effect of self-affirmation on women’s intellectual performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(2), 236-243.

- Martens, A., Johns, M., Greenberg, J., & Schimel, J. (2006). Combating stereotype threat: The effect of self-affirmation on women’s intellectual performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(2), 236-243.

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. J. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications (pp. 3–34). New York: Basic.

- National Spelling Bee. (2014a). Statistics. Retrieved from: http://www.spellingbee.com/statistics

- National Spelling Bee. (2014b). Get to Know the Competition. Retrieved from: http://www.spellingbee.com/UserFiles/topblog—-good2341418.html

- Neisser, U., Boodoo, G., Bouchard, Jr., T.J., Boykin, A. W., Brody, N., Ceci, S., Halpern, D., Loehlin, J. C., Perloff, R., Sternberg, R. J. & Urbina, S. (1996). Intelligence: Knowns and unknowns. American Psychologist, 51, 77-101.

- Nisbett, R. E., Aronson, J., Blair, C., Dickens, W., Flynn, J., Halpern, D. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2012). Intelligence: new findings and theoretical developments. American Psychologist, 67(2), 130-160.

- Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. E. (1998). The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: Practical and theoretical implications of 85 years of research findings. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 262–274

- Spearman, C. (1904). ” General Intelligence,” Objectively Determined and Measured. The American Journal of Psychology, 15(2), 201-292.

- Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(1), 4-28.

- Terman, L. M. (1916). The measurement of intelligence: An explanation of and a complete guide for the use of the Stanford revision and extension of the Binet-Simon Intelligence Scale. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Terman, L. M. (1916). The measurement of intelligence: An explanation of and a complete guide for the use of the Stanford revision and extension of the Binet-Simon Intelligence Scale. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Wechsler, D. (1955). Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Oxford: Psychological Corporation.

How to cite this Chapter using APA Style:

Biswas-Diener, R. (2019). Intelligence. Adapted for use by Queen’s University. Original chapter in R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology.Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/ncb2h79v

Copyright and Acknowledgment:

This material is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.en_US.

This material is attributed to the Diener Education Fund (copyright © 2018) and can be accessed via this link: http://noba.to/ncb2h79v.

Additional information about the Diener Education Fund (DEF) can be accessed here.