39 Emerging Adulthood

Original chapter by Jeffrey Jensen Arnet adapted by the Queen’s University Psychology Department

This Open Access chapter was originally written for the NOBA project. Information on the NOBA project can be found below.

Emerging adulthood has been proposed as a new life stage between adolescence and young adulthood, lasting roughly from ages 18 to 25. Five features make emerging adulthood distinctive: identity explorations, instability, self-focus, feeling in-between adolescence and adulthood, and a sense of broad possibilities for the future. Emerging adulthood is found mainly in developed countries, where most young people obtain tertiary education and median ages of entering marriage and parenthood are around 30. There are variations in emerging adulthood within developed countries. It lasts longest in Europe, and in Asian developed countries, the self-focused freedom of emerging adulthood is balanced by obligations to parents and by conservative views of sexuality. In developing countries, although today emerging adulthood exists only among the middle-class elite, it can be expected to grow in the 21st century as these countries become more affluent.

Learning Objectives

- Explain where, when, and why a new life stage of emerging adulthood appeared over the past half-century.

- Identify the five features that distinguish emerging adulthood from other life stages.

- Describe the variations in emerging adulthood in countries around the world.

Introduction

Think for a moment about the lives of your grandparents and great-grandparents when they were in their twenties. How do their lives at that age compare to your life? If they were like most other people of their time, their lives were quite different than yours. What happened to change the twenties so much between their time and our own? And how should we understand the 18–25 age period today?

The theory of emerging adulthood proposes that a new life stage has arisen between adolescence and young adulthood over the past half-century in industrialized countries. Fifty years ago, most young people in these countries had entered stable adult roles in love and work by their late teens or early twenties. Relatively few people pursued education or training beyond secondary school, and, consequently, most young men were full-time workers by the end of their teens. Relatively few women worked in occupations outside the home, and the median marriage age for women in the United States and in most other industrialized countries in 1960 was around 20 (Arnett & Taber, 1994; Douglass, 2005). The median marriage age for men was around 22, and married couples usually had their first child about one year after their wedding day. All told, for most young people half a century ago, their teenage adolescence led quickly and directly to stable adult roles in love and work by their late teens or early twenties. These roles would form the structure of their adult lives for decades to come.

Now all that has changed. A higher proportion of young people than ever before—about 70% in the United States—pursue education and training beyond secondary school (National Center for Education Statistics, 2012). The early twenties are not a time of entering stable adult work but a time of immense job instability: In the United States, the average number of job changes from ages 20 to 29 is seven. The median age of entering marriage in the United States is now 27 for women and 29 for men (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2011). Consequently, a new stage of the life span, emerging adulthood, has been created, lasting from the late teens through the mid-twenties, roughly ages 18 to 25.

The Five Features of Emerging Adulthood

Five characteristics distinguish emerging adulthood from other life stages (Arnett, 2004). Emerging adulthood is:

- the age of identity explorations;

- the age of instability;

- the self-focused age;

- the age of feeling in-between; and

- the age of possibilities.

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of emerging adulthood is that it is the age of identity explorations. That is, it is an age when people explore various possibilities in love and work as they move toward making enduring choices. Through trying out these different possibilities, they develop a more definite identity, including an understanding of who they are, what their capabilities and limitations are, what their beliefs and values are, and how they fit into the society around them. Erik Erikson (1950), who was the first to develop the idea of identity, proposed that it is mainly an issue in adolescence; but that was more than 50 years ago, and today it is mainly in emerging adulthood that identity explorations take place (Côté, 2006).

The explorations of emerging adulthood also make it the age of instability. As emerging adults explore different possibilities in love and work, their lives are often unstable. A good illustration of this instability is their frequent moves from one residence to another. Rates of residential change in American society are much higher at ages 18 to 29 than at any other period of life (Arnett, 2004). This reflects the explorations going on in emerging adults’ lives. Some move out of their parents’ household for the first time in their late teens to attend a residential college, whereas others move out simply to be independent (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). They may move again when they drop out of college or when they graduate. They may move to cohabit with a romantic partner, and then move out when the relationship ends. Some move to another part of the country or the world to study or work. For nearly half of American emerging adults, residential change includes moving back in with their parents at least once (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). In some countries, such as in southern Europe, emerging adults remain in their parents’ home rather than move out; nevertheless, they may still experience instability in education, work, and love relationships (Douglass, 2005, 2007).

Emerging adulthood is also a self-focused age. Most American emerging adults move out of their parents’ home at age 18 or 19 and do not marry or have their first child until at least their late twenties (Arnett, 2004). Even in countries where emerging adults remain in their parents’ home through their early twenties, as in southern Europe and in Asian countries such as Japan, they establish a more independent lifestyle than they had as adolescents (Rosenberger, 2007). Emerging adulthood is a time between adolescents’ reliance on parents and adults’ long-term commitments in love and work, and during these years, emerging adults focus on themselves as they develop the knowledge, skills, and self-understanding they will need for adult life. In the course of emerging adulthood, they learn to make independent decisions about everything from what to have for dinner to whether or not to get married.

Another distinctive feature of emerging adulthood is that it is an age of feeling in-between, not adolescent but not fully adult, either. When asked, “Do you feel that you have reached adulthood?” the majority of emerging adults respond neither yes nor no but with the ambiguous “in some ways yes, in some ways no” (Arnett, 2003, 2012). It is only when people reach their late twenties and early thirties that a clear majority feels adult. Most emerging adults have the subjective feeling of being in a transitional period of life, on the way to adulthood but not there yet. This “in-between” feeling in emerging adulthood has been found in a wide range of countries, including Argentina (Facio & Micocci, 2003), Austria (Sirsch, Dreher, Mayr, & Willinger, 2009), Israel (Mayseless & Scharf, 2003), the Czech Republic (Macek, Bejček, & Vaníčková, 2007), and China (Nelson & Chen, 2007).

Finally, emerging adulthood is the age of possibilities, when many different futures remain possible, and when little about a person’s direction in life has been decided for certain. It tends to be an age of high hopes and great expectations, in part because few of their dreams have been tested in the fires of real life. In one national survey of 18- to 24-year-olds in the United States, nearly all—89%—agreed with the statement, “I am confident that one day I will get to where I want to be in life” (Arnett & Schwab, 2012). This optimism in emerging adulthood has been found in other countries as well (Nelson & Chen, 2007).

International Variations

The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood originally were based on research involving about 300 Americans between ages 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions (Arnett, 2004). To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally?

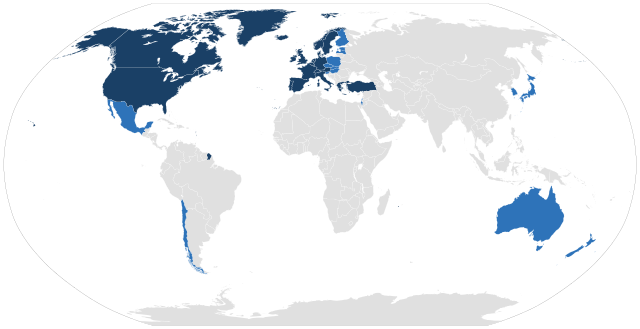

The answer to this question depends greatly on what part of the world is considered. Demographers make a useful distinction between the developing countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population and the economically developed countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), including the United States, Canada, western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The current population of OECD countries (also called developed countries) is 1.2 billion, about 18% of the total world population (UNDP, 2011). The rest of the human population resides in developing countries, which have much lower median incomes; much lower median educational attainment; and much higher incidence of illness, disease, and early death. Let us consider emerging adulthood in OECD countries first, then in developing countries.

EA in OECD Countries: The Advantages of Affluence

The same demographic changes as described above for the United States have taken place in other OECD countries as well. This is true of participation in postsecondary education as well as median ages for entering marriage and parenthood (UNdata, 2010). However, there is also substantial variability in how emerging adulthood is experienced across OECD countries. Europe is the region where emerging adulthood is longest and most leisurely. The median ages for entering marriage and parenthood are near 30 in most European countries (Douglass, 2007). Europe today is the location of the most affluent, generous, and egalitarian societies in the world—in fact, in human history (Arnett, 2007). Governments pay for tertiary education, assist young people in finding jobs, and provide generous unemployment benefits for those who cannot find work. In northern Europe, many governments also provide housing support. Emerging adults in European societies make the most of these advantages, gradually making their way to adulthood during their twenties while enjoying travel and leisure with friends.

The lives of Asian emerging adults in developed countries such as Japan and South Korea are in some ways similar to the lives of emerging adults in Europe and in some ways strikingly different. Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults tend to enter marriage and parenthood around age 30 (Arnett, 2011). Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults in Japan and South Korea enjoy the benefits of living in affluent societies with generous social welfare systems that provide support for them in making the transition to adulthood—for example, free university education and substantial unemployment benefits.

However, in other ways, the experience of emerging adulthood in Asian OECD countries is markedly different than in Europe. Europe has a long history of individualism, and today’s emerging adults carry that legacy with them in their focus on self-development and leisure during emerging adulthood. In contrast, Asian cultures have a shared cultural history emphasizing collectivism and family obligations. Although Asian cultures have become more individualistic in recent decades as a consequence of globalization, the legacy of collectivism persists in the lives of emerging adults. They pursue identity explorations and self-development during emerging adulthood, like their American and European counterparts, but within narrower boundaries set by their sense of obligations to others, especially their parents (Phinney & Baldelomar, 2011). For example, in their views of the most important criteria for becoming an adult, emerging adults in the United States and Europe consistently rank financial independence among the most important markers of adulthood. In contrast, emerging adults with an Asian cultural background especially emphasize becoming capable of supporting parents financially as among the most important criteria (Arnett, 2003; Nelson, Badger, & Wu, 2004). This sense of family obligation may curtail their identity explorations in emerging adulthood to some extent, as they pay more heed to their parents’ wishes about what they should study, what job they should take, and where they should live than emerging adults do in the West (Rosenberger, 2007).

Another notable contrast between Western and Asian emerging adults is in their sexuality. In the West, premarital sex is normative by the late teens, more than a decade before most people enter marriage. In the United States and Canada, and in northern and eastern Europe, cohabitation is also normative; most people have at least one cohabiting partnership before marriage. In southern Europe, cohabiting is still taboo, but premarital sex is tolerated in emerging adulthood. In contrast, both premarital sex and cohabitation remain rare and forbidden throughout Asia. Even dating is discouraged until the late twenties, when it would be a prelude to a serious relationship leading to marriage. In cross-cultural comparisons, about three fourths of emerging adults in the United States and Europe report having had premarital sexual relations by age 20, versus less than one fifth in Japan and South Korea (Hatfield and Rapson, 2006).

EA in Developing Countries: Low But Rising

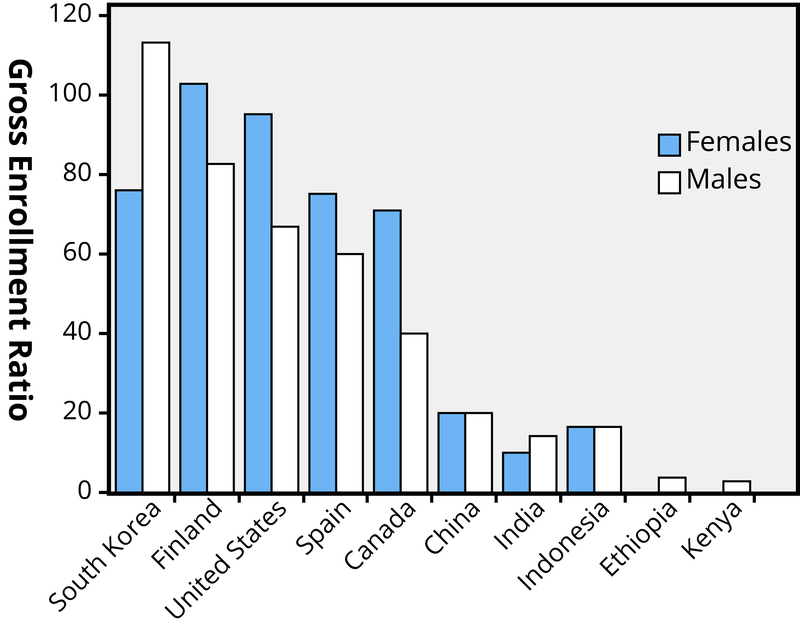

Emerging adulthood is well established as a normative life stage in the developed countries described thus far, but it is still growing in developing countries. Demographically, in developing countries as in OECD countries, the median ages for entering marriage and parenthood have been rising in recent decades, and an increasing proportion of young people have obtained post-secondary education. Nevertheless, currently it is only a minority of young people in developing countries who experience anything resembling emerging adulthood. The majority of the population still marries around age 20 and has long finished education by the late teens. As you can see in Figure 1, rates of enrollment in tertiary education are much lower in developing countries (represented by the five countries on the right) than in OECD countries (represented by the five countries on the left).

For young people in developing countries, emerging adulthood exists only for the wealthier segment of society, mainly the urban middle class, whereas the rural and urban poor—the majority of the population—have no emerging adulthood and may even have no adolescence because they enter adult-like work at an early age and also begin marriage and parenthood relatively early. What Saraswathi and Larson (2002) observed about adolescence applies to emerging adulthood as well: “In many ways, the lives of middle-class youth in India, South East Asia, and Europe have more in common with each other than they do with those of poor youth in their own countries.” However, as globalization proceeds, and economic development along with it, the proportion of young people who experience emerging adulthood will increase as the middle class expands. By the end of the 21st century, emerging adulthood is likely to be normative worldwide.

Conclusion

The new life stage of emerging adulthood has spread rapidly in the past half-century and is continuing to spread. Now that the transition to adulthood is later than in the past, is this change positive or negative for emerging adults and their societies? Certainly there are some negatives. It means that young people are dependent on their parents for longer than in the past, and they take longer to become full contributing members of their societies. A substantial proportion of them have trouble sorting through the opportunities available to them and struggle with anxiety and depression, even though most are optimistic. However, there are advantages to having this new life stage as well. By waiting until at least their late twenties to take on the full range of adult responsibilities, emerging adults are able to focus on obtaining enough education and training to prepare themselves for the demands of today’s information- and technology-based economy. Also, it seems likely that if young people make crucial decisions about love and work in their late twenties or early thirties rather than their late teens and early twenties, their judgment will be more mature and they will have a better chance of making choices that will work out well for them in the long run.

What can societies do to enhance the likelihood that emerging adults will make a successful transition to adulthood? One important step would be to expand the opportunities for obtaining tertiary education. The tertiary education systems of OECD countries were constructed at a time when the economy was much different, and they have not expanded at the rate needed to serve all the emerging adults who need such education. Furthermore, in some countries, such as the United States, the cost of tertiary education has risen steeply and is often unaffordable to many young people. In developing countries, tertiary education systems are even smaller and less able to accommodate their emerging adults. Across the world, societies would be wise to strive to make it possible for every emerging adult to receive tertiary education, free of charge. There could be no better investment for preparing young people for the economy of the future.

Check Your Knowledge

To help you with your studying, we’ve included some practice questions for this module. These questions do not necessarily address all content in this module. They are intended as practice, and you are responsible for all of the content in this module even if there is no associated practice question. To promote deeper engagement with the material, we encourage you to create some questions of your own for your practice. You can then also return to these self-generated questions later in the course to test yourself.

Vocabulary

- Collectivism

- Belief system that emphasizes the duties and obligations that each person has toward others.

- Developed countries

- The economically advanced countries of the world, in which most of the world’s wealth is concentrated.

- Developing countries

- The less economically advanced countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population. Most are currently developing at a rapid rate.

- Emerging adulthood

- A new life stage extending from approximately ages 18 to 25, during which the foundation of an adult life is gradually constructed in love and work. Primary features include identity explorations, instability, focus on self-development, feeling incompletely adult, and a broad sense of possibilities.

- Individualism

- Belief system that exalts freedom, independence, and individual choice as high values.

- OECD countries

- Members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, comprised of the world’s wealthiest countries.

- Tertiary education

- Education or training beyond secondary school, usually taking place in a college, university, or vocational training program.

References

- Arnett, J. J. (2012). New horizons in emerging and young adulthood. In A. Booth & N. Crouter (Eds.), Early adulthood in a family context (pp. 231–244). New York, NY: Springer.

- Arnett, J. J. (2011). Emerging adulthood(s): The cultural psychology of a new life stage. In L.A. Jensen (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental psychology: New syntheses in theory, research, and policy (pp. 255–275). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from late teens through the twenties. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Arnett, J. J. (2003). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 63–75.

- Arnett, J. J., & Taber, S. (1994). Adolescence terminable and interminable: When does adolescence end? Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 23, 517–537.

- Arnett, J. J. & Schwab, J. (2012). The Clark University poll of emerging adults: Thriving, struggling, & hopeful. Worcester, MA: Clark University.

- Arnett, J.J. (2007). The long and leisurely route: Coming of age in Europe today. Current History, 106, 130-136.

- Côté, J. (2006). Emerging adulthood as an institutionalized moratorium: Risks and benefits to identity formation. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century(pp. 85–116). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press.

- Douglass, C. B. (2007). From duty to desire: Emerging adulthood in Europe and its consequences. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 101–108.

- Douglass, C. B. (2007). From duty to desire: Emerging adulthood in Europe and its consequences. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 101–108.

- Douglass, C. B. (2005). Barren states: The population “implosion” in Europe. New York, NY: Berg.

- Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York, NY: Norton.

- Facio, A., & Micocci, F. (2003). Emerging adulthood in Argentina. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 21–31

- Goldscheider, F., & Goldscheider, C. (1999). The changing transition to adulthood: Leaving and returning home. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hatfield, E., & Rapson, R. L. (2006). Love and sex: Cross-cultural perspectives. New York, NY: University Press of America.

- Macek, P., Bejček, J., & Vaníčková, J. (2007). Contemporary Czech emerging adults: Generation growing up in the period of social changes. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 444–475.

- Mayseless, O., & Scharf, M. (2003). What does it mean to be an adult? The Israeli experience. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 5–20.

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2012). The condition of education, 2012. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from http://www.nces.gov

- Nelson, L. J., & Chen, X. (2007) Emerging adulthood in China: The role of social and cultural factors. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 86–91.

- Nelson, L. J., Badger, S., & Wu, B. (2004). The influence of culture in emerging adulthood: Perspectives of Chinese college students. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 26–36.

- Phinney, J. S. & Baldelomar, O. A. (2011). Identity development in multiple cultural contexts. In L. A. Jensen (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental psychology: New syntheses in theory, research and policy (pp. 161-186). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Rosenberger, N. (2007). Rethinking emerging adulthood in Japan: Perspectives from long-term single women. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 92–95.

- Saraswathi, T. S., & Larson, R. (2002). Adolescence in global perspective: An agenda for social policy. In B. B. Brown, R. Larson, & T. S. Saraswathi, (Eds.), The world’s youth: Adolescence in eight regions of the globe (pp. 344–362). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Sirsch, U., Dreher, E., Mayr, E., & Willinger, U. (2009). What does it take to be an adult in Austria? Views of adulthood in Austrian adolescents, emerging adults, and adults.Journal of Adolescent Research, 24, 275–292.

- U.S. Bureau of the Census (2011). Statistical abstract of the United States. Washington, DC: Author.

- UNdata (2010). Gross enrollment ratio in tertiary education. United Nations Statistics Division. Retrieved November 5, 2010, from http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=GenderStat&f=inID:68

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2011). Human development report. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

How to cite this Chapter using APA Style:

Arnett, J. J. (2019). Emerging adulthood. Adapted for use by Queen’s University. Original chapter in R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology.Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/3vtfyajs

Copyright and Acknowledgment:

This material is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.en_US.

This material is attributed to the Diener Education Fund (copyright © 2018) and can be accessed via this link: http://noba.to/3vtfyajs.

Additional information about the Diener Education Fund (DEF) can be accessed here.

Arnett, J. J., & Taber, S. (1994). Adolescence terminable and interminable: When does adolescence end? Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 23, 517–537.

Douglass, C. B. (2005). Barren states: The population “implosion” in Europe. New York, NY: Berg.

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2012). The condition of education, 2012. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from http://www.nces.gov

U.S. Bureau of the Census (2011). Statistical abstract of the United States. Washington, DC: Author.

A new life stage extending from approximately ages 18 to 25, during which the foundation of an adult life is gradually constructed in love and work. Primary features include identity explorations, instability, focus on self-development, feeling incompletely adult, and a broad sense of possibilities.

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from late teens through the twenties. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York, NY: Norton.

Côté, J. (2006). Emerging adulthood as an institutionalized moratorium: Risks and benefits to identity formation. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 85–116). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press.

Goldscheider, F., & Goldscheider, C. (1999). The changing transition to adulthood: Leaving and returning home. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Douglass, C. B. (2007). From duty to desire: Emerging adulthood in Europe and its consequences. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 101–108.

Rosenberger, N. (2007). Rethinking emerging adulthood in Japan: Perspectives from long-term single women. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 92–95.

Arnett, J. J. (2003). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 63–75.

Arnett, J. J. (2012). New horizons in emerging and young adulthood. In A. Booth & N. Crouter (Eds.), Early adulthood in a family context (pp. 231–244). New York, NY: Springer.

Facio, A., & Micocci, F. (2003). Emerging adulthood in Argentina. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 21–31

Sirsch, U., Dreher, E., Mayr, E., & Willinger, U. (2009). What does it take to be an adult in Austria? Views of adulthood in Austrian adolescents, emerging adults, and adults.Journal of Adolescent Research, 24, 275–292.

Mayseless, O., & Scharf, M. (2003). What does it mean to be an adult? The Israeli experience. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 5–20.

Macek, P., Bejček, J., & Vaníčková, J. (2007). Contemporary Czech emerging adults: Generation growing up in the period of social changes. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 444–475.

Nelson, L. J., & Chen, X. (2007) Emerging adulthood in China: The role of social and cultural factors. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 86–91.

Arnett, J. J. & Schwab, J. (2012). The Clark University poll of emerging adults: Thriving, struggling, & hopeful. Worcester, MA: Clark University.

Members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, comprised of the world’s wealthiest countries.

The economically advanced countries of the world, in which most of the world’s wealth is concentrated.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2011). Human development report. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

The less economically advanced countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population. Most are currently developing at a rapid rate.

UNdata (2010). Gross enrollment ratio in tertiary education. United Nations Statistics Division. Retrieved November 5, 2010, from http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=GenderStat&f=inID:68

Arnett, J.J. (2007). The long and leisurely route: Coming of age in Europe today. Current History, 106, 130-136.

Education or training beyond secondary school, usually taking place in a college, university, or vocational training program.

Arnett, J. J. (2011). Emerging adulthood(s): The cultural psychology of a new life stage. In L.A. Jensen (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental psychology: New syntheses in theory, research, and policy (pp. 255–275). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Belief system that exalts freedom, independence, and individual choice as high values.

Belief system that emphasizes the duties and obligations that each person has toward others.

Phinney, J. S. & Baldelomar, O. A. (2011). Identity development in multiple cultural contexts. In L. A. Jensen (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental psychology: New syntheses in theory, research and policy (pp. 161-186). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Nelson, L. J., Badger, S., & Wu, B. (2004). The influence of culture in emerging adulthood: Perspectives of Chinese college students. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 26–36.