4. Framework for Project Management

Adrienne Watt

Many different professions contribute to the theory and practice of project management. Engineers and architects have been managing major projects since pre-history. Since approximately the 1960s, there have been efforts to professionalize the practice of project management as a specialization of its own. There are many active debates around this: Should project management be a profession in the same way as engineering, accounting, and medicine? These have professional associations that certify who is legally allowed to use the job title, and who can legally practice the profession. They also provide a level of assurance of quality and discipline members who behave inappropriately. Another ongoing debate is: How much industry knowledge is required of a seasoned project manager? How easily can a project manager from one industry, say, IT, transition to another industry such as hospitality?

There are two major organizations with worldwide impact on the practice of project management: the Project Management Institute (PMI), with world headquarters in the United States, and the International Project Management Association (IPMA), with world headquarters in Switzerland. This textbook takes an approach that is closer to the PMI approach. More details are included in this chapter, along with a section on the project management office.

Project Management Institute Overview

Five volunteers founded the Project Management Institute (PMI) in 1969. Their initial goal was to establish an organization where members could share their experiences in project management and discuss issues. Today, PMI is a non-profit project management professional association and the most widely recognized organization in terms of promoting project management best practices. PMI was formed to serve the interests of the project management industry. The premise of PMI is that the tools and techniques of project management are common even among the widespread application of projects from the software to the construction industry. PMI first began offering the Project Management Professional (PMP) certification exam in 1984. Although it took a while for people to take notice, now more than 590,000 individuals around the world hold the PMP designation.

To help keep project management terms and concepts clear and consistent, PMI introduced the book A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) in 1987. It was updated it in 1996, 2000, 2004, 2009, and most recently in 2013 as the fifth edition. At present, there are more than one million copies of the PMBOK Guide in circulation. The highly regarded Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) has adopted it as their project management standard. In 1999 PMI was accredited as an American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standards developer and also has the distinction of being the first organization to have its certification program attain International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 9001 recognition. In 2008, the organization reported more than 260,000 members in over 171 countries. PMI has its headquarters in Pennsylvania, United States, and also has offices in Washington, DC, and in Canada, Mexico, and China, as well as having regional service centers in Singapore, Brussels (Belgium), and New Delhi (India). Recently, an office was opened in Mumbai (India).

Because of the importance of projects, the discipline of project management has evolved into a working body of knowledge known as PMBOK – Project Management Body of Knowledge. The PMI is responsible for developing and promoting PMBOK. PMI also administers a professional certification program for project managers, the PMP. So if you want to get grounded in project management, PMBOK is the place to start, and if you want to make project management your profession, then you should consider becoming a PMP.

So what is PMBOK?

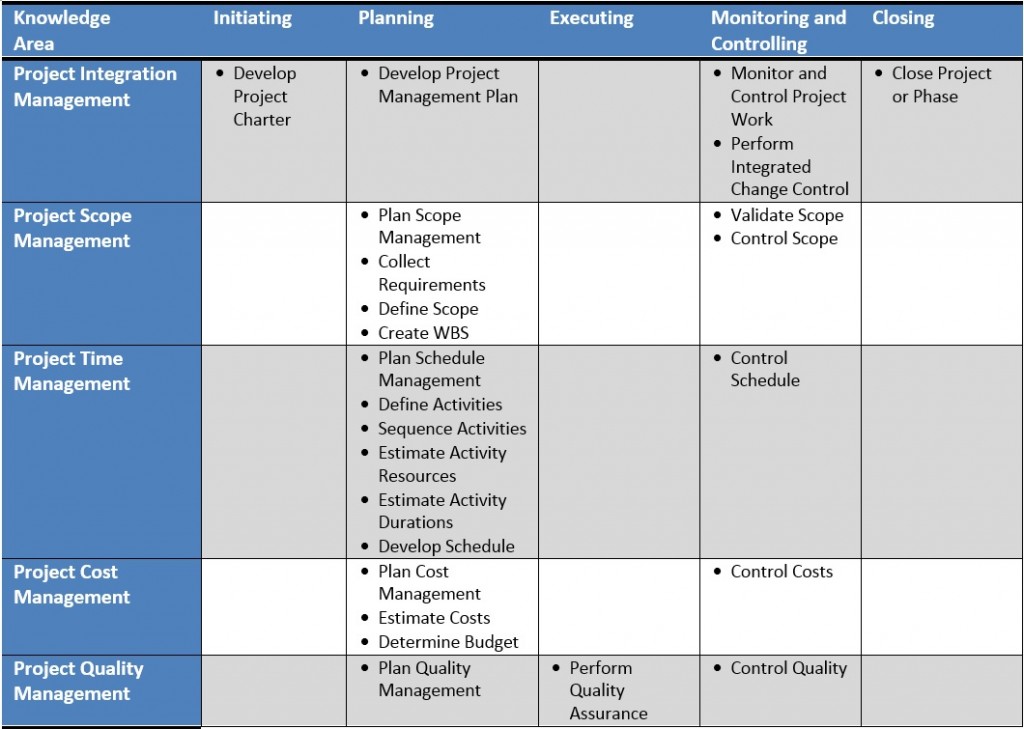

PMBOK is the fundamental knowledge you need for managing a project, categorized into 10 knowledge areas:

- Managing integration: Projects have all types of activities going on and there is a need to keep the “whole” thing moving collectively – integrating all of the dynamics that take place. Managing integration is about developing the project charter, scope statement, and plan to direct, manage, monitor, and control project change.

- Managing scope: Projects need to have a defined parameter or scope, and this must be broken down and managed through a work breakdown structure or WBS. Managing scope is about planning, definition, WBS creation, verification, and control.

- Managing time/schedule: Projects have a definite beginning and a definite ending date. Therefore, there is a need to manage the budgeted time according to a project schedule. Managing time/schedule is about definition, sequencing, resource and duration estimating, schedule development, and schedule control.

- Managing costs: Projects consume resources, and therefore, there is a need to manage the investment with the realization of creating value (i.e., the benefits derived exceed the amount spent). Managing costs is about resource planning, cost estimating, budgeting, and control.

- Managing quality: Projects involve specific deliverables or work products. These deliverables need to meet project objectives and performance standards. Managing quality is about quality planning, quality assurance, and quality control.

- Managing human resources: Projects consist of teams and you need to manage project team(s) during the life cycle of the project. Finding the right people, managing their outputs, and keeping them on schedule is a big part of managing a project. Managing human resources is about human resources planning, hiring, and developing and managing a project team.

- Managing communication: Projects invariably touch lots of people, not just the end users (customers) who benefit directly from the project outcomes. This can include project participants, managers who oversee the project, and external stakeholders who have an interest in the success of the project. Managing communication is about communications planning, information distribution, performance reporting, and stakeholder management.

- Managing risk: Projects are a discovery-driven process, often uncovering new customer needs and identifying critical issues not previously disclosed. Projects also encounter unexpected events, such as project team members resigning, budgeted resources suddenly changing, the organization becoming unstable, and newer technologies being introduced. There is a real need to properly identify various risks and manage these risks. Managing risk is about risk planning and identification, risk analysis (qualitative and quantitative), risk response (action) planning, and risk monitoring and control.

- Managing procurement: Projects procure the services of outside vendors and contractors, including the purchase of equipment. There is a need to manage how vendors are selected and managed within the project life cycle. Managing procurement is about acquisition and contracting plans, sellers’ responses and selections, contract administration, and contract closure.

- Managing stakeholders: Every project impacts people and organizations and is impacted by people and organizations. Identifying these stakeholders early, and as they arise and change throughout the project, is a key success factor. Managing stakeholders is about identifying stakeholders, their interest level, and their potential to influence the project; and managing and controlling the relationships and communications between stakeholders and the project.

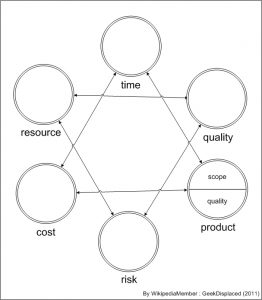

This is the big framework for managing projects and if you want to be effective in managing projects, then you need to be effective in managing each of the 10 knowledge areas that make up PMBOK (see Figure 4.1)

Certification in project management is available from the PMI, PRINCE2, ITIL, Critical Chain, and others. Agile project management methodologies (Scrum, extreme programming, Lean Six Sigma, others) also have certifications.

Introduction to the Project Management Knowledge Areas

As discussed above, projects are divided into components, and a project manager must be knowledgeable in each area. Each of these areas of knowledge will be explored in more depth in subsequent chapters. For now, lets look at them in a little more detail to prepare you for the chapters that follow.

Project Start-Up and Integration

The start-up of a project is similar to the start-up of a new organization. The project leader develops the project infrastructure used to design and execute the project. The project management team must develop alignment among the major stakeholders—those who have a share or interest—on the project during the early phases or definition phases of the project. The project manager will conduct one or more kickoff meetings or alignment sessions to bring the various parties of the project together and begin the project team building required to operate efficiently during the project.

During project start-up, the project management team refines the scope of work and develops a preliminary schedule and conceptual budget. The project team builds a plan for executing the project based on the project profile. The plan for developing and tracking the detailed schedule, the procurement plan, and the plan for building the budget and estimating and tracking costs are developed during the start-up. The plans for information technology, communication, and tracking client satisfaction are also all developed during the start-up phase of the project.

Flowcharts, diagrams, and responsibility matrices are tools to capture the work processes associated with executing the project plan. The first draft of the project procedures manual captures the historic and intuitional knowledge that team members bring to the project. The development and review of these procedures and work processes contribute to the development of the organizational structure of the project.

This is typically an exciting time on a project where all things are possible. The project management team is working many hours developing the initial plan, staffing the project, and building relationships with the client. The project manager sets the tone of the project and sets expectations for each of the project team members. The project start-up phase on complex projects can be chaotic, and until plans are developed, the project manager becomes the source of information and direction. The project manager creates an environment that encourages team members to fully engage in the project and encourages innovative approaches to developing the project plan.

Project Scope

The project scope is a document that defines the parameters—factors that define a system and determine its behavior—of the project, what work is done within the boundaries of the project, and the work that is outside the project boundaries. The scope of work (SOW) is typically a written document that defines what work will be accomplished by the end of the project—the deliverables of the project. The project scope defines what will be done, and the project execution plan defines how the work will be accomplished.

No template works for all projects. Some projects have a very detailed scope of work, and some have a short summary document. The quality of the scope is measured by the ability of the project manager and project stakeholders to develop and maintain a common understanding of what products or services the project will deliver. The size and detail of the project scope is related to the complexity profile of the project. A more complex project often requires a more detailed and comprehensive scope document.

According to the PMI, the scope statement should include the following:

- Description of the scope

- Product acceptance criteria

- Project deliverables

- Project exclusions

- Project constraints

- Project assumptions

The scope document is the basis for agreement by all parties. A clear project scope document is also critical to managing change on a project. Since the project scope reflects what work will be accomplished on the project, any change in expectations that is not captured and documented creates the opportunity for confusion. One of the most common trends on projects is the incremental expansion in the project scope. This trend is labeled “scope creep.” Scope creep threatens the success of a project because the small increases in scope require additional resources that were not in the plan. Increasing the scope of the project is a common occurrence, and adjustments are made to the project budget and schedule to account for these changes. Scope creep occurs when these changes are not recognized or not managed. The ability of a project manager to identify potential changes is often related to the quality of the scope documents.

Events do occur that require the scope of the project to change. Changes in the marketplace may require change in a product design or the timing of the product delivery. Changes in the client’s management team or the financial health of the client may also result in changes in the project scope. Changes in the project schedule, budget, or product quality will have an effect on the project plan. Generally, the later in the project the change occurs, the greater the increase to the project costs. Establishing a change management system for the project that captures changes to the project scope and assures that these changes are authorized by the appropriate level of management in the client’s organization is the responsibility of the project manager. The project manager also analyzes the cost and schedule impact of these changes and adjusts the project plan to reflect the changes authorized by the client. Changes to the scope can cause costs to increase or decrease.

Project Schedule and Time Management

The definition of project success often includes completing the project on time. The development and management of a project schedule that will complete the project on time is a primary responsibility of the project manager, and completing the project on time requires the development of a realistic plan and the effective management of the plan. On smaller projects, project managers may lead the development of the project plan and build a schedule to meet that plan. On larger and more complex projects, a project controls team that focuses on both costs and schedule planning and controlling functions will assist the project management team in developing the plan and tracking progress against the plan.

To develop the project schedule, the project team does an analysis of the project scope, contract, and other information that helps the team define the project deliverables. Based on this information, the project team develops a milestone schedule. The milestone schedule establishes key dates throughout the life of a project that must be met for the project to finish on time. The key dates are often established to meet contractual obligations or established intervals that will reflect appropriate progress for the project. For less complex projects, a milestone schedule may be sufficient for tracking the progress of the project. For more complex projects, a more detailed schedule is required.

To develop a more detailed schedule, the project team first develops a work breakdown structure (WBS)—a description of tasks arranged in layers of detail. Although the project scope is the primary document for developing the WBS, the WBS incorporates all project deliverables and reflects any documents or information that clarifies the project deliverables. From the WBS, a project plan is developed. The project plan lists the activities that are needed to accomplish the work identified in the WBS. The more detailed the WBS, the more activities that are identified to accomplish the work.

After the project team identifies the activities, the team sequences the activities according to the order in which the activities are to be accomplished. An outcome from the work process is the project logic diagram. The logic diagram represents the logical sequence of the activities needed to complete the project. The next step in the planning process is to develop an estimation of the time it will take to accomplish each activity or the activity duration. Some activities must be done sequentially, and some activities can be done concurrently. The planning process creates a project schedule by scheduling activities in a way that effectively and efficiently uses project resources and completes the project in the shortest time.

On larger projects, several paths are created that represent a sequence of activities from the beginning to the end of the project. The longest path to the completion of the project is the critical path. If the critical path takes less time than is allowed by the client to complete the project, the project has a positive total float or project slack. If the client’s project completion date precedes the calculated critical path end date, the project has a negative float. Understanding and managing activities on the critical path is an important project management skill.

To successfully manage a project, the project manager must also know how to accelerate a schedule to compensate for unanticipated events that delay critical activities. Compressing—crashing—the schedule is a term used to describe the techniques used to shorten the project schedule. During the life of the project, scheduling conflicts often occur, and the project manager is responsible for reducing these conflicts while maintaining project quality and meeting cost goals.

Project Costs

The definition of project success often includes completing the project within budget. Developing and controlling a project budget that will accomplish the project objectives is a critical project management skill. Although clients expect the project to be executed efficiently, cost pressures vary on projects. On some projects, the project completion or end date is the largest contributor to the project complexity. The development of a new drug to address a critical health issue, the production of a new product that will generate critical cash flow for a company, and the competitive advantage for a company to be first in the marketplace with a new technology are examples of projects with schedule pressures that override project costs.

The accuracy of the project budget is related to the amount of information known by the project team. In the early stages of the project, the amount of information needed to develop a detailed budget is often missing. To address the lack of information, the project team develops different levels of project budget estimates. The conceptual estimate (or “ballpark estimate”) is developed with the least amount of knowledge. The major input into the conceptual estimate is expert knowledge or past experience. A project manager who has executed a similar project in the past can use those costs to estimate the costs of the current project.

When more information is known, the project team can develop a rough order of magnitude (ROM) estimate. Additional information such as the approximate square feet of a building, the production capacity of a plant, and the approximate number of hours needed to develop a software program can provide a basis for providing a ROM estimate. After a project design is more complete, a project detailed estimate can be developed. For example, when the project team knows the number of rooms, the type of materials, and the building location of a home, they can provide a detailed estimate. A detailed estimate is not a bid.

The cost of the project is tracked relative to the progress of the work and the estimate for accomplishing that work. Based on the cost estimate, the cost of the work performed is compared against the cost budgeted for that work. If the cost is significantly higher or lower, the project team explores reasons for the difference between expected costs and actual costs.

Project costs may deviate from the budget because the prices in the marketplace were different from what was expected. For example, the estimated costs for lumber on a housing project may be higher than budgeted or the hourly cost for labor may be lower than budgeted. Project costs may also deviate based on project performance. For example, a project team estimated that the steel design for a bridge over a river would take 800 labor hours, but 846 hours were actually expended. The project team captures the deviation between costs budgeted for work and the actual cost for work, revises the estimate as needed, and takes corrective action if the deviation appears to reflect a trend.

The project manager is responsible for assuring that the project team develops cost estimates based on the best information available and revises those estimates as new or better information becomes available. The project manager is also responsible for tracking costs against the budget and conducting an analysis when project costs deviate significantly from the project estimate. The project manager then takes appropriate corrective action to ensure that project performance matches the revised project plan.

Project Quality

Project quality focuses on the end product or service deliverables that reflect the purpose of the project. The project manager is responsible for developing a project execution approach that provides for a clear understanding of the expected project deliverables and the quality specifications. The project manager of a housing construction project not only needs to understand which rooms in the house will be carpeted but also what grade of carpet is needed. A room with a high volume of traffic will need a high-grade carpet.

The project manager is responsible for developing a project quality plan that defines the quality expectations and ensures that the specifications and expectations are met. Developing a good understanding of the project deliverables through documenting specifications and expectations is critical to a good quality plan. The processes for ensuring that the specifications and expectations are met are integrated into the project execution plan. Just as the project budget and completion dates may change over the life of a project, the project specifications may also change. Changes in quality specifications are typically managed in the same process as cost or schedule changes. The impact of the changes is analyzed for impact on cost and schedule, and with appropriate approvals, changes are made to the project execution plan.

The PMI’s A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) has an extensive chapter on project quality management. The material found in this chapter would be similar to material found in a good operational management text.

Although any of the quality management techniques designed to make incremental improvement to work processes can be applied to a project work process, the character of a project (unique and relatively short in duration) makes small improvements less attractive on projects. Rework on projects, as with manufacturing operations, increases the cost of the product or service and often increases the time needed to complete the reworked activities. Because of the duration constraints of a project, the development of the appropriate skills, materials, and work processes early in the project is critical to project success. On more complex projects, time is allocated to developing a plan to understand and develop the appropriate levels of skills and work processes.

Project management organizations that execute several similar types of projects may find process improvement tools useful in identifying and improving the baseline processes used on their projects. Process improvement tools may also be helpful in identifying cost and schedule improvement opportunities. Opportunities for improvement must be found quickly to influence project performance. The investment in time and resources to find improvements is greatest during the early stages of the project, when the project is in the planning stages. During later project stages, as pressures to meet project schedule goals increase, the culture of the project is less conducive to making changes in work processes.

Another opportunity for applying process improvement tools is on projects that have repetitive processes. A housing contractor that is building several identical houses may benefit from evaluating work processes in the first few houses to explore the opportunities available to improve the work processes. The investment of $1,000 in a work process that saves $200 per house is a good investment as long as the contractor is building more than five houses.

Project Team: Human Resources and Communications

Staffing the project with the right skills, at the right place, and at the right time is an important responsibility of the project management team. The project usually has two types of team members: functional managers and process managers. The functional managers and team focus on the technology of the project. On a construction project, the functional managers would include the engineering manager and construction superintendents. On a training project, the functional manager would include the professional trainers; on an information technology project, the software development managers would be functional managers. The project management team also includes project process managers. The project controls team would include process managers who have expertise in estimating, cost tracking, planning, and scheduling. The project manager needs functional and process expertise to plan and execute a successful project.

Because projects are temporary, the staffing plan for a project typically reflects both the long-term goals of skilled team members needed for the project and short-term commitment that reflects the nature of the project. Exact start and end dates for team members are often negotiated to best meet the needs of individuals and the project. The staffing plan is also determined by the different phases of the project. Team members needed in the early or conceptual phases of the project are often not needed during the later phases or project closeout phases. Team members needed during the implementation phase are often not needed during the conceptual or closeout phases. Each phase has staffing requirements, and the staffing of a complex project requires detailed planning to have the right skills, at the right place, at the right time.

Typically a core project management team is dedicated to the project from start-up to closeout. This core team would include members of the project management team: project manager, project controls, project procurement, and key members of the function management or experts in the technology of the project. Although longer projects may experience more team turnover than shorter projects, it is important on all projects to have team members who can provide continuity through the project phases.

For example, on a large commercial building project, the civil engineering team that designs the site work where the building will be constructed would make their largest contribution during the early phases of the design. The civil engineering lead would bring on different civil engineering specialties as they were needed. As the civil engineering work is completed and the structural engineering is well underway, a large portion of the civil engineers would be released from the project. The functional managers, the engineering manager, and civil engineering lead would provide expertise during the entire length of the project, addressing technical questions that may arise and addressing change requests.

Project team members can be assigned to the project from a number of different sources. The organization that charters the project can assign talented managers and staff from functional units within the organization, contract with individuals or agencies to staff positions on the project, temporarily hire staff for the project, or use any combination of these staffing options. This staffing approach allows the project manager to create the project organizational culture. Some project cultures are more structured and detail oriented, and some are less structured with less formal roles and communication requirements. The type of culture the project manager creates depends greatly on the type of project.

Communications

Completing a complex project successfully requires teamwork, and teamwork requires good communication among team members. If those team members work in the same building, they can arrange regular meetings, simply stop by each other’s office space to get a quick answer, or even discuss a project informally at other office functions. Many complex projects in today’s global economy involve team members from widely separated locations, and the types of meetings that work within the same building are not possible. Teams that use electronic methods of communicating without face-to-face meetings are called virtual teams.

Communicating can be divided into two categories: synchronous and asynchronous. If all the parties to the communication are taking part in the exchange at the same time, the communication is synchronous. A telephone conference call is an example of synchronous communication. When the participants are not interacting at the same time, the communication is asynchronous. (The letter a at the beginning of the word means not.) Communications technologies require a variety of compatible devices, software, and service providers, and communication with a global virtual team can involve many different time zones. Establishing effective communications requires a communications plan.

Project Risk

Risk exists on all projects. The role of the project management team is to understand the kinds and levels of risks on the project and then to develop and implement plans to mitigate these risks. Risk represents the likelihood that an event will happen during the life of the project that will negatively affect the achievement of project goals. The type and amount of risk varies by industry type, complexity, and phase of the project. The project risk plan will also reflect the risk profile of the project manager and key stakeholders. People have different comfort levels with risk, and some members of the project team will be more risk averse than others.

The first step in developing a risk management plan involves identifying potential project risks. Some risks are easy to identify, such as the potential for a damaging storm in the Caribbean, and some are less obvious. Many industries or companies have risk checklists developed from past experience. The Construction Industry Institute published a 100-item risk checklist that provides examples and areas of project risks. No risk checklist will include all potential risks. The value of a checklist is the stimulation of discussion and thought about the potential risks on a project.

The project team analyzes the identified risks and estimates the likelihood of the risks occurring. The team then estimates the potential impact on project goals if the event does occur. The outcome from this process is a prioritized list of estimated project risks with a value that represents the likelihood of occurrence and the potential impact on the project.

The project team then develops a risk mitigation plan that reduces the likelihood of an event occurring or reduces the impact on the project if the event does occur. The risk management plan is integrated into the project execution plan, and mitigation activities are assigned to the appropriate project team member. The likelihood that all the potential events identified in the risk analysis would occur is extremely rare. The likelihood that one or more events will happen is high.

The project risk plan reflects the risk profile of the project and balances the investment of the mitigation against the benefit for the project. One of the more common risk mitigation approaches is the use of contingency. Contingency is funds set aside by the project team to address unforeseen events. Projects with a high-risk profile will typically have a large contingency budget. If the team knows which activities have the highest risk, contingency can be allocated to activities with the highest risk. When risks are less identifiable to specific activities, contingency is identified in a separate line item. The plan includes periodic risk-plan reviews during the life of the project. The risk review evaluates the effectiveness of the current plan and explores possible risks not identified in earlier sessions.

Project Procurement

The procurement effort on projects varies widely and depends on the type of project. Often the client organization will provide procurement services on less complex projects. In this case, the project team identifies the materials, equipment, and supplies needed by the project and provides product specifications and a detailed delivery schedule. When the procurement department of the parent organization provides procurement services, a liaison from the project can help the procurement team better understand the unique requirements of the project and the time-sensitive or critical items of the project schedule.

On larger, more complex projects, personnel are dedicated to procuring and managing the equipment, supplies, and materials needed by the project. Because of the temporary nature of projects, equipment, supplies, and materials are procured as part of the product of the project or for the execution of the project. For example, the bricks procured for a construction project would be procured for the product of the project, and the mortar mixer would be equipment procured for the execution of the project work. At the end of the project, equipment bought or rented for the execution of the work of the project are sold, returned to rental organizations, or disposed of some other way.

More complex projects will typically procure through different procurement and management methods. Commodities are common products that are purchased based on the lowest bid. Commodities include items like concrete for building projects, office supplies, or even lab equipment for a research project. The second type of procurement includes products that are specified for the project. Vendors who can produce these products bid for a contract. The awarding of a contract can include price, ability to meet the project schedule, the fit for purpose of the product, and other considerations important to the project. Manufacturing a furnace for a new steel mill would be provided by a project vendor. Equipment especially designed and built for a research project is another example. These vendors’ performances become important parts of the project, and the project manager assigns resources to coordinate the work and schedule of the vendor. The third procurement approach is the development of one or more partners. A design firm that is awarded the design contract for a major part of the steel mill and a research firm that is conducting critical subparts of the research are examples of potential project partners. A partner contributes to and is integrated into the execution plan. Partners perform best when they share the project vision of success and are emotionally invested in the project. The project management team builds and implements a project procurement plan that recognizes the most efficient and effective procurement approach to support the project schedule and goals.

Project Stakeholder Management

People and organizations can have many different relationships to the project. Most commonly, these relationships can be grouped into those who will be impacted by the project and those who can impact the project.

A successful project manager will identify stakeholders early in the project. For each stakeholder, it is important to identify what they want or need and what influence or power they have over the project. Based on this information, the need to communicate with the stakeholder or stakeholder group can be identified, followed by the creation of a stakeholder management plan. A stakeholder register is used to identify and track the interactions between the project and each stakeholder. This register must be updated on a regular basis, as new stakeholders can arise at any time, and the needs and interest levels of a particular stakeholder may change through the course of the project.

Source: A.Watt

Scrum Development Overview

“Scrum” is another formal project management/product development methodology and part of agile project management. Scrum is a term from rugby (scrimmage) that means a way of restarting a game. It’s like restarting the project efforts every X weeks. It’s based on the idea that you do not really know how to plan the whole project up front, so you start and build empirical data, and then re-plan and iterate from there.

Scrum uses sequential sprints for development. Sprints are like small project phases (ideally two to four weeks). The idea is to take one day to plan for what can be done now, then develop what was planned for, and demonstrate it at the end of the sprint. Scrum uses a short daily meeting of the development team to check what was done yesterday, what is planned for the next day, and what if anything is impeding the team members from accomplishing what they have committed to. At the end of the sprint, what has been demonstrated can then be tested, and the next sprint cycle starts.

Scrum methodology defines several major roles. They are:

- Product owners: essentially the business owner of the project who knows the industry, the market, the customers, and the business goals of the project. The product owner must be intimately involved with the Scrum process, especially the planning and the demonstration parts of the sprint.

- Scrum Master: somewhat like a project manager, but not exactly. The Scrum Master’s duties are essentially to remove barriers that impede the progress of the development team, teach the product owner how to maximize return on investment (ROI) in terms of development effort, facilitate creativity and empowerment of the team, improve the productivity of the team, improve engineering practices and tools, run daily standup meetings, track progress, and ensure the health of the team.

- Development team: self-organizing (light-touch leadership), empowered group; they participate in planning and estimating for each sprint, do the development, and demonstrate the results at the end of the sprint. It has been shown that the ideal size for a development team is 7 +/- 2. The development team can be broken into “teamlets” that “swarm” on user stories, which are created in the sprint planning session.

Typically, the way a product is developed is that there is a “front burner” (which has stories/tasks for the current sprint), a “back burner” (which has stories for the next sprint), and a “fridge” (which has stories for later, as well as process changes). One can look at a product as having been broken down like this: product -> features -> stories -> tasks.

Often effort estimations are done using “story points” (tiny = 1 SP, small = 2 SP, medium = 4 SP, large = 8 SP, big = 16+ SP, unknown = ? SP) Stories can be of various types. User stories are very common and are descriptions of what the user can do and what happens as a result of different actions from a given starting point. Other types of stories are from these areas: analysis, development, QA, documentation, installation, localization, and training.

Planning meetings for each sprint require participation by the product owner, the Scrum Master, and the development team. In the planning meeting, they set the goals for the upcoming sprint and select a subset of the product backlog (proposed stories) to work on. The development team decomposes stories to tasks and estimates them. The development team and product owner do final negotiations to determine the backlog for the following sprint.

The Scrum methodology uses metrics to help with future planning and tracking of progress; for example, “burn down” – the number of hours remaining in the sprint versus the time in days; “velocity” – essentially, the amount of effort the team expends. (After approximately three sprints with the same team, one can get a feel for what the team can do going forward.)

Some caveats about using Scrum methodology: 1) You need committed, mature developers; 2) You still need to do major requirements definition, some analysis, architecture definition, and definition of roles and terms up front or early; 3) You need commitment from the company and the product owner; and 4) It is best for products that require frequent new releases or updates, and less effective for large, totally new products that will not allow for frequent upgrades once they are released.

The Project Management Office

Many large and even medium-sized organizations have created a department to oversee and support projects throughout the organization. This is an attempt to reduce the high numbers of failed projects (see the Project Management Overview chapter.) These offices are usually called the project management office or PMO.

The PMO may be the home of all the project managers in an organization, or it may simply be a resource for all project managers, who report to their line areas.

Typical objectives of a PMO are:

- Help ensure that projects are aligned with organizational objectives

- Provide templates and procedures for use by project managers

- Provide training and mentorship

- Provide facilitation

- Stay abreast of the latest trends in project management

- Serve as a repository for project reports and lessons learned

The existence and role of PMOs tends to be somewhat fluid. If a PMO is created, and greater success is not experienced in organizational projects, the PMO is at risk of being disbanded as a cost-saving measure. If an organization in which you are a project manager or a project team member has a PMO, try to make good use of the resources available. If you are employed as a resource person in a PMO, remember that your role is not to get in the way and create red tape, but to enable and enhance the success of project managers and projects within the organization.

Attribution

This chapter of Project Management is a derivative copy of Project Management by Merrie Barron and Andrew Barron licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported and Project Management From Simple to Complex by Russel Darnall, John Preston, Eastern Michigan University licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported.