8.2 Identifying Inherent Risks

Inherent risks are those that are generally associated with and considered to be an unavoidable or naturally occurring part of a particular activity. Knee injuries from playing soccer, getting sunburned while playing outdoors on a hot sunny day, pulling a hamstring during a fitness class, or cutting a finger during a cooking workshop are all considered inherent risks; risks that would not be present if the activity were not being offered or engaged in. In organizations, inherent risks can be identified by walking around and/or talking with staff, volunteers, and participants in 5 areas:

- Facilities – Maintenance, up-keep, damage, vandalism

- Equipment – worn, damaged, broken; age-appropriate, activity-appropriate

- Personnel – adequate supervision, qualifications

- Program/event/activity – location, activities, security, etc.

- Participants – medical history, readiness for the activity, ability, mental/emotional state

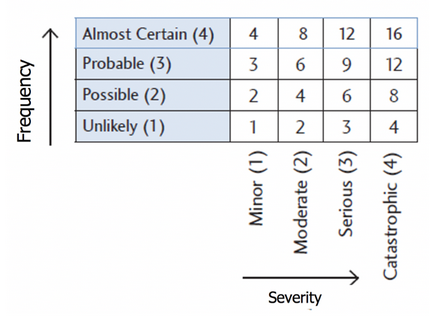

Risk Management Matrix

The magnitude (size) of a risk can be determined by using a simple formula:

Frequency × Severity = Magnitude

The term Frequency refers to the likelihood of an injury/damage/loss occurring. The term Severity refers to the seriousness of the resulting injury/damage/loss. In the formula, a points system is applied to both Frequency and Severity, from 1-4:

Frequency (1-4)

1 – Unlikely – less likely to happen than not

2 – Possible – just as likely to happen as not

3 – Probable – more likely to happen than not

4 – Almost certain – sure to happen

Severity (1-4)

1 – Minor = will have an impact, BUT can be dealt with through internal adjustments

2 – Moderate = will have an impact and will require a change

3 – Serious = will have a significant impact

4 – Catastrophic = will have a debilitating impact

After determining the Frequency (1-4) and the Severity (1-4) of a given risk, multiply the two numbers to arrive at the Magnitude of the risk (from 1-16 points). The higher the number, the higher the potential for a catastrophic outcome. It can be expressed in chart format:

Identify-Assess-Manage-Review (IAMR)

IAMR is a Risk Management process tool that can be applied by anyone involved in the planning, leading or evaluating of a recreation activity.

Identify

- List all the potential risks inherent to the activity

- Examine what else could go wrong (within reason) in the indoor or outdoor space(s) where the activity is taking place.

- Environmental Domain (Environmental Hazards): Things in the immediate environment that pose a danger where the activity is happening, indoors or outdoors. Outdoor examples include severe weather, animal encounters, rocky or uneven terrain, proximity to water elements, and broken equipment. Indoor examples include exposed electrical wires, sagging ceiling tiles, and trip hazards like loose carpeting or cables.

- Human Domain (Human Hazards): Things to do with the human condition that pose a danger to participants, indoors or outdoors, before or during the activity. Examples include participant or leader fatigue, lack of qualifications or experience (leader), unresolved conflicts among participants, hunger, anger, leader immaturity, over-estimation of participant capabilities, and lack of emergency procedures.

- Note: In any given recreational activity, the number and severity of Human Hazards almost always outweigh Environmental Hazards.

Assess

- After identifying each individual risk (there can be many), each gets assessed for its magnitude using the Frequency × Severity = Magnitude formula.

Manage

There are four primary ways in which risks can be effectively managed:

- Accept – When an organization or activity leader is prepared to accept the risk(s) of having participants take part in a specific activity. The activity leader(s) deems the risk minor enough to be acceptable and leaves it as is (e.g., a paper cut while doing an Origami paper-folding activity).

- The programmer must be very aware of public perception (optics) when making the decision to accept a risk

- Used most frequently when the consequences are small and the frequency low

- Be aware that if something does go wrong, the public will be quick to pass judgment and demand to know, “WHAT WERE YOU THINKING?!”

- Reduce – Judging that risk is acceptable but serious enough to require proactive reduction, often through modification of the activity (like adding frequent hydration breaks) or the addition of safety equipment (ie, helmets, safety goggles, application of sunscreen

- Transfer – Liability for the risk is transferred from the activity leader/agency to an insurance provider, often by means of a participant signing a waiver or assumption of risk form. In the event of an accident or incident (barring gross negligence on behalf of the provider), accountability falls to the participant and the burden of responsibility to the insurance provider.

A Note about Waivers:

-

- Signed waivers and/or Assumption of Risk forms can effectively distancing the organization from responsibility, however, waivers do not absolve activity leaders or agencies from showing a Duty of Care

- When signed, a waiver is legally binding

- Waivers discourage lawsuits. They can heighten a participant’s awareness that they have a role to play in ensuring their own safety. If a participant is injured during the course of an activity, a signed waiver ‘proves’ the participant was aware of the risks when they chose to participate

- Only adults can sign waivers (18+ yrs). You cannot waive the rights of a child

- Waivers can bring an aura of seriousness to an activity prior to engaging in it (ie; white-water rafting, rock-climbing, zip-lining)

- Eliminate (Avoid) – The most extreme course of action: Judging that a risk associated with an activity could be severe or catastrophic, the activity is therefore eliminated or avoided. Sometimes, ELIMINATING a behaviour or specific activity is clearly the safest and arguably most correct course of action. For example:

- The elimination of tackle football in some Canadian high schools

- The prohibition of body-checking at all levels of recreational hockey divisions in Ontario (with the exception of competitive divisions)

- Camps eliminating games or activities that have historically caused physical injuries like British Bulldog, Piggyback Races, or building human pyramids).

When you remove the activity, you remove the risk. However, elimination is rarely seen as the best answer to reducing risk, as going to this extreme often means destroying the very nature or aims of a given activity, like the thrill that comes with bungee-jumping or free-diving, or the feelings of joy that comes after a successful outing with a group of adults with complex health concerns.

Review

“Review” is a crucially important step in the Risk Management Process.

- The recreation leader reflects on how effectively risks were managed in a given activity.

- Questions to ask: What could have gone better? Were there any unexpected safety issues or risks that occurred that needed to be noted so they could be addressed proactively next time?

- The Review step establishes if there is anything the recreation leader will do differently the next time they run this activity.