Conflict and Conflict Management

Conflict may occur between people or within groups in all kinds of situations. Due to the wide range of differences among people, the lack of conflict may signal the absence of effective interaction. Conflict should not be considered good or bad, rather it may be viewed as a necessity to help build meaningful relationships between people and groups. The means and how the conflict is handled will determine whether it is productive or devastating. Conflict has a potential to create positive opportunities and advancement towards a common goal, however, conflict can also devastate relationships and lead to negative outcomes ((Kazimoto, 2013; Fisher, 2000; Evans, 2013).

Defining Conflict

What is conflict? The answer to this question varies, depending on the source. The Webster Dictionary defines conflict as “the competitive or opposing action of incompatibles: an antagonistic state or action.” For some, the definition of conflict may involve war, military fight, or political dispute. For others, conflict involves a disagreement that arises when two or more people or parties pursue a common goal. Conflict means different things to different people, making it very difficult to come up with a universal or true definition. To complicate this even further, when one party may feel that they are in a conflict situation, the other party may think that they are just in a simple discussion about differing opinions (Fisher, 2000; Evans, 2013; Conflict, 2011).

To fully understand conflict and how to manage it, we first need to establish a definition that will allow us to effectively discuss conflict management and its use by today’s leaders. Conflict can be described as a disagreement among two entities that may be portrayed by antagonism or hostility. This is usually fueled by the opposition of one party to another to reach an objective that is different from the other, even though both parties are working towards a common goal (Fisher, 2000; Evans, 2013). To help us better understand what conflict is, we need to analyze its possible sources. According to American psychologist Daniel Katz, conflict may arise from 3 different sources: economic, value, and power. (Evans, 2013)

- Economic Conflict involves competing motives to attain scarce resources. This type of conflict typically occurs when behavior and emotions of each party are aimed at increasing their own gain. Each party involved may come into conflict as a result of them trying to attain the most of these resources. An example of this is when union and management conflict on how to divide and distribute company funds (Fisher, 2000; Evans, 2013).

- Value Conflict involves incompatibility in the ways of life. This type of conflict includes the different preferences and ideologies that people may have as their principles. This type of conflict is very difficult to resolve because the differences are belief-based and not fact-based. An example of this is demonstrated in international war in which each side asserts its own set of beliefs (Fisher, 2000; Evans, 2013).

- Power Conflict occurs when each party tries to exert and maintain its maximum influence in the relationship and social setting. For one party to have influence over the other, one party must be stronger (in terms of influence) than the other. This will result in a power struggle that may end in winning, losing, or a deadlock with continuous tension between both parties. This type of conflict may occur between individuals, groups, or nations. This conflict will come into play when one party chooses to take a power approach to the relationship. The key word here is “chooses.” The power conflict is a choice that is made by one party to exert its influence on the other. It is also important to note that power may enter all types of conflict since the parties are trying to control each other (Fisher, 2000; Evans, 2013).

According to Ana Shetach, an organizational consultant in team process and development, conflict can be a result from every aspect such as attitude, race, gender, looks, education, opinions, feelings, religion and cultures. Conflict may also arise from differences in values, affiliations, roles, positions, and status. Even though it seems that there is a vast array of sources for conflict, most conflict is not of a pure type and typically is a mixture of several sources (Shetach, 2012).

Conflict is an inevitable part of life and occurs naturally during our daily activities. There will always be differences of opinions or disagreements between individuals and/or groups. Conflict is a basic part of the human experience and can influence our actions or decisions in one way or another. It should not be viewed as an action that always results in negative outcomes but instead as an opportunity for learning and growth which may lead to positive outcomes. We can reach positive outcomes through effective conflict management and resolution, which will be discussed in more detail later in the chapter (Evans, 2013).

Since conflict can result in emotions that can make a situation uncomfortable, it is often avoided. Feelings such as guilt, anger, anxiety, and fear can be a direct result of conflict, which can cause individuals to avoid it all together. Conflict can be a good thing and avoiding it to preserve a false impression of harmony can cause even more damage (Loehr, 2017a). If we analyze the CPP Global Human Capital Report, we see evidence that conflict can lead to positive outcomes within the workplace environment. This research project asked 5000 individuals about their experiences with conflict in the workplace environment. They reported, that as a result of conflict:

- 41% of respondents had better understanding of others

- 33% of respondents had improved working relationships

- 29% of respondents found a better solution to a problem

- 21% of respondents saw higher performance in the team

- 18% of respondents felt increased motivation (CPP Global Human Capital Report, 2008)

Based on this report, we can conclude that conflict can lead to positive outcomes and increased productivity, depending on the conflict itself (Loehr, 2017a). Approximately 76% of the respondents reported that conflict resulted in some type of positive outcome. This speaks volumes to the ideology that conflict within the workplace is something that should be welcomed and not avoided (CPP Global Human Capital Report, 2008).

Conflict can occur in various ways in the human experience, whether it is within one-self between differing ideas or between people. Even though this chapter will focus on the conflict at the social level, it is important that we review all the different levels of conflict that may exist. The levels of conflict that we will discuss include interpersonal, intrapersonal, intergroup, and intragroup conflict (Loehr, 2017a; Fisher, 2000; Evans, 2013).

Levels of Conflict

- Interpersonal Conflict. This level of conflict occurs when two individuals have differing goals or approaches in their relationship. Each individual has their own type of personality, and because of this, there will always be differences in choices and opinions. Compromise is necessary for managing this type of conflict and can eventually help lead to personal growth and developing relationships with others. If interpersonal conflict is not addressed, it can become destructive to the point where a mediator (leader) may be needed (Loehr, 2017a; Fisher, 2000; Evans, 2013).

- Intrapersonal Conflict. This level of conflict occurs within an individual and takes place within the person’s mind. This is a physiological type of conflict that can involve thoughts and emotions, desires, values, and principles. This type of conflict can be difficult to resolve if the individual has trouble interpreting their own inner battles. It may lead to symptoms that can become physically apparent, such as anxiety, restlessness, or even depression. This level of conflict can create other levels of conflict if the individual is unable to come to a resolution on their own. An individual who is unable to come to terms on their own inner conflicts may allow this to affect their relationships with other individuals and therefore create interpersonal conflict. Typically, it is best for an individual dealing with intrapersonal conflict to communicate with others who may help them resolve their conflict and help relieve them of the situation (Loehr, 2017a; Fisher, 2000; Evans, 2013).

- Intergroup/Interprofessional Conflict. This level of conflict occurs when two different groups or teams within the same organization have a disagreement. This may be a result of competition for resources, differences in goals or interests, or even threats to group identity. This type of conflict can be very destructive and escalate very quickly if not resolved effectively. This can ultimately lead to high costs for the organization or poor patient outcomes. On the other hand, intergroup conflict can lead to remarkable progress towards a positive outcome for the organization if it is managed appropriately (Loehr, 2017a; Fisher, 2000; Evans, 2013).

- Intragroup Conflict. This level of conflict can occur between two individuals who are within the same group or team. Similar to interpersonal conflict, disagreements between team members typically are a result of different personalities. Within a team, conflict can be very beneficial as it can lead to progress to accomplishing team objectives and goals. However, if intragroup conflict is not managed correctly, it can disrupt the harmony of the entire team and result in slowed productivity (Loehr, 2017a; Fisher, 2000; Evans, 2013).

Regardless of the level of conflict that takes place, there are several methods that can be employed to help manage conflicts. And with the seemingly infinite triggers for conflict, management of conflict is a constant challenge for leaders. To help address this, we will next discuss what conflict management is and then later examine the role of leadership in conflict management and resolution.

Conflict Management

Conflict Management may be defined as the process of reducing negative outcomes of conflict while increasing the positive. Effectively managed conflicts can lead to a resolution that will result in positive outcomes and productivity for the team and/or organization (Loehr, 2017b; Evans, 2013). MRTs need to be able to manage conflict when it occurs, and their ability to manage them is critical to the success of the individuals and/or teams involved (Guttman, 2004). There are several models available for leaders to use when determining their conflict management behavior.

As shown in Figure 3.5, you can consider several strategies to prevent or manage conflict including:

- Use a client-centred approach to frame discussions.

- Use an evidence-informed approach to make decisions.

- Be open to hearing varying disciplinary perspectives.

- Engage in self-reflection.

- Engage in respectful discussions.

- Reflect on the perspectives of all team members.

- Share your perspective and rationale.

Figure: Conflict management strategies.

First, use a client-centred approach. This ensures the focus is on the client as a whole person and that the patient is cared for in ways that respect their “autonomy, voice, self-determination, and participation” in their own care (Registered Nurses Association of Ontario, 2006).

Second, use an evidence-informed approach. This will help you critically engage in discussions that are informed by the evidence, rather than personal preference.

Third, it is essential that you be open to hearing, respectfully discussing, and reflecting on the perspectives of all team members (Lyndon et al., 2011). In addition to sharing your perspective, share the rationale for it. Along with a client-centred and evidence-informed approach, this kind of effective dialogue will benefit the person who is the focus of care and decisions: the client.

DESC Framework for Managing conflicts

Conflict is not uncommon on interprofessional teams, especially when there are diverse perspectives from multiple staff regarding patient care. MRTs must be prepared to manage conflict to support the needs of their team members. When conflict occurs, the DESC tool can be used to help resolve conflict by using “I statements.” DESC is a mnemonic that stands for the following:

- D: Describe the specific situation or behavior; provide concrete data.

- E: Express how the situation makes you feel/what your concerns are using “I” statements.

- S: Suggest other alternatives and seek agreement.

- C: Consequences stated in terms of impact on established team goals while striving for consensus (AHRQ, 2014).

The DESC tool should be implemented in a private area with a focus on WHAT is right, not WHO is right.

The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI)

The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument is an assessment tool that helps measure an individual’s behavior in conflict situations. The assessment takes less than 15 minutes to complete and provides feedback to an individual about how effectively they can use five different conflict-handling modes. TKI helps leaders understand how individual or team dynamics are affected by each of the modes, as well as helping leaders decide on which mode to employ in different conflict situations (Kilmann & Thomas, n.d.).

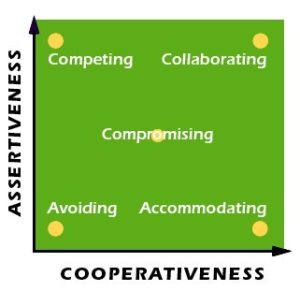

The TKI is based on two dimensions of behavior that help characterize the five different conflict-handling modes. The first dimension is assertiveness, and this describes the extent to which a person will try to fulfill their own concerns. The second is cooperativeness, and this describes the extent to which a person will try to fulfil others’ concerns. The five conflict-handling modes fall within a scale of assertiveness and cooperativeness as shown in the figure below. They include: avoiding, accommodating, competing, collaborating, and compromising (Loehr, 2017b; Kilmann & Thomas, n.d.).

(source:killmanndiagnostics.com)

The TKI Five Conflict-Handling Modes (Avoiding, Accommodating, Competing, Collaborating, and Compromising)

Avoiding

This mode is low assertiveness and low cooperative. The MRT withdraws from the conflict, and therefore no one wins. They do not pursue their own concerns nor the concerns of others. The leader may deal with the conflict in a passive attitude in hopes that the situation just “resolves itself.” In many cases, avoiding conflict may be effective and beneficial, but on the other hand, it prevents the matter from being resolved and can lead to larger issues. Situations when this mode is useful include: when emotions are elevated and everyone involved needs time to calm down so that productive discussions can take place, the issue is of low importance, the team is able to resolve the conflict without participation from leadership, there are more important matters that need to be addressed, and the benefit of avoiding the conflict outweighs the benefit of addressing it. This mode should not be used when the conflict needs to be resolved in a timely manner and when the reason for ignoring the conflict is just that (Loehr, 2017a; Mediate.com; Kilmann & Thomas, n.d.).

Accommodating

This mode is low assertiveness and high cooperation. The MRT ignores their own concerns in order to fulfill the concerns of others. They are willing to sacrifice their own needs to “keep the peace” within the team. Therefore, the leader loses and the other person or party wins. This mode can be effective, as it can yield an immediate solution to the issue but may also reveal the MRT as a “doormat” who will accommodate to anyone who causes conflict. Situations when this mode is useful include: when an individual realizes they are wrong and accepts a better solution, when the issue is more important to the other person or party which can be seen as a good gesture and builds social credits for future use, when damage may result if the MRT continues to push their own agenda, when an MRT wants to allow the team to develop and learn from their own mistakes, and when harmony needs to be maintained to avoid trouble within the team. This mode should not be used when the outcome is critical to the success of the team and when safety is an absolute necessity to the resolution of the conflict (Loehr, 2017b; Mediate.com; Kilmann & Thomas, n.d.).

Competing

This mode is high assertiveness and low cooperation. The MRT fulfills their own concerns at the expense of others. The MRT uses any appropriate power they have to win the conflict. This is a powerful and effective conflict-handling mode and can be appropriate and necessary in certain situations. The misuse of this mode can lead to new conflict; therefore, MRTs who use this conflict-handling mode need to be mindful of this possibility so that they are able to reach a productive resolution. Situations when this mode is useful include: an immediate decision is needed, an outcome is critical and cannot be compromised, strong leadership needs to be demonstrated, unpopular actions are needed, when company or organizational welfare is at stake, and when self-interests need to be protected. This mode should be avoided when: relationships are strained and may lead to retaliation, the outcome is not very important to the MRT, it may result in weakened support and commitment from followers, and when the MRT is not very knowledgeable of the situation (Loehr, 2017b; Mediate.com; Kilmann & Thomas, n.d.).

Collaborating

This mode is high assertiveness and high cooperation. In this mode both individuals or teams win the conflict. The MRT works with the team to ensure that a resolution is met that fulfills both of their concerns. This mode will require a lot of time, energy and resources to identify the underlying needs of each party. This mode is often described as “putting an idea on top of an idea on top of an idea” to help develop the best resolution to a conflict that will satisfy all parties involved. The best resolution in this mode is typically a solution to the conflict that would not have been produced by a single individual. Many leaders encourage collaboration because not only can it lead to positive outcomes, but more importantly it can result in stronger team structure and creativity. Situations when this mode is useful include: the concerns of parties involved are too important to be compromised, to identify and resolve feelings that have been interfering with team dynamics, to improve team structure and commitment, to merge ideas from individuals with different viewpoints on a situation, and when the objective is to learn. This mode should be avoided in situations where time, energy and resources are limited, a quick and vital decision needs to be made, and the conflict itself is not worth the time and effort (Loehr, 2017b; Mediate.com; Kilmann & Thomas, n.d.).

Compromising

This mode is moderate assertiveness and moderate cooperative. It is often described as “giving up more than one would want” to allow for each individual to have their concerns partially fulfilled. This can be viewed as a situation where neither person wins or losses, but rather as an acceptable solution that is reached by either splitting the difference between the two positions, trading concerns, or seeking a middle ground. MRTs who use this conflict-handling mode may be able to produce acceptable outcomes but may put themselves in a situation where team members will take advantage of the them. This can be a result of the team knowing that their leader will compromise during negotiations. Compromising can also lead to a less optimal outcome because less effort is needed to use this mode. Situations when this mode is effective include: a temporary and/or quick decision to a complex issue is needed, the welfare of the organization will benefit from the compromise of both parties, both parties are of equal power and rank, when other modes of conflict-handling are not working, and when the goals are moderately important and not worth the time and effort. This mode should be avoided when partial satisfaction of each party’s concerns may lead to propagation of the issue or when a leader recognizes that their team is taking advantage of their compromising style (Loehr, 2017b; Mediate.com; Kilmann & Thomas, n.d.).

MRTs should be capable of using all five conflict-handling modes and should not limit themselves to using only one mode during times of conflict (Loehr, 2017b). MRTs must be able to adapt to different conflict situations and recognize which type of conflict-handling mode is best to employ given the conflict at hand (Mediate.com). The use of these modes can result in positive or negative resolutions and it is imperative that today’s leaders understand how to effectively employ them (Loehr, 2017b; Mediate.com; Kilmann & Thomas, n.d.).

Points of Consideration

The positive lens of conflict

A starting point is to transform how you view conflict. Have you ever considered viewing conflict from a positive lens? Conflict suggests that you have an opinion that you hold as meaningful or important. In itself, this is a good thing. It can be beneficial to approach conflict as an opportunity. You can learn and grow by truly listening to another person’s view and sharing your own. Part of this is seeking to understand what the perceived threat is for you and for the other person(s). If approached professionally, this sharing can help you feel good that you have shared your opinion, why it matters to you, and participated collaboratively and respectfully to manage the conflict. Additionally, by learning and growing while engaging professionally with another person, this can sometimes create a connection that cultivates your relationship with them. It can also add to a positive resolution related to the conflict with the potential for creative and divergent thinking.

Conflict Management Approach to Resolution

Conflict resolution is about finding a reasonable solution to varying perspectives. This may involve you and the other person(s) sharing your perspective to enhance understanding of the issue. It may result in you or the other person shifting your perspective in a way that a reasonable solution is arrived upon related to the conflict. Often, when conversation goes beyond the disagreement on the surface and instead explores the perceived or actual threat on each side, more options for compromise and resolving the conflict emerge.

Professionalism should always guide how you approach and manage conflict. In educational institutions and in medical radiation technology, professionalism is essential. As a student, specifically an MRT student, you are developing your professional self as an MRT. This means that you have a responsibility to uphold values of honesty, respect, and integrity in all your interactions.

Engaging in effective conflict resolution takes practice. Remember, as an MRT student, you are learning and growing in so many ways. As such, engaging in reflection on how you participate in conflict resolution in terms of what was effective and what was not effective is important to your professional development.

Fortunately, conflict resolution is a skill that you can learn, and that is a good thing. There are several conflict resolution strategies that can inform your communication:

- Approach the situation with a “spirit of inquiry” (Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, 2007, p. 26).

- You should enter the discussion with an open mind and strive to understand the other person’s perspective.

- Reflect on what the perceived or actual threat is for you, and seek to understand what the other person(s)’ perceived or actual threat is. This may be a very different conversation from the issue that started the conflict.

- Assume the goodwill of another person.

- This means avoid entering a situation with a negative attitude. It is best to assume the other person’s willingness to engage in kind and professional discussions. However, do note that assuming goodwill does not mean that the other person will end up agreeing with your perspective or behave in that manner. It may be that after a full discussion, you agree to disagree.

- Use “I” statements when you engage in conflict resolution.

- These statements are important because they convey how you feel (from your standpoint) and open the opportunity for discussion. “I” statements are difficult to counter-argue because they are your perspective on the situation, as opposed to “you” statements which insinuate knowing the other person’s position without understanding and can lead to accusations and feelings of blame.

- Do not raise your voice.

- Raising your voice is not helpful to resolve a conflict, it escalates the situation and makes people defensive. There is a famous quote by Desmond Tutu, who says “Don’t raise your voice, improve your argument.”

- In email, avoid capital letters, bolding and exclamation marks as it can be interpreted as shouting or anger. Also, never write anything in an email that you would not directly say to a person.

- Be clear and provide rationale for your perspective.

- This strategy can help the other person understand your perspective.

Points of Consideration

Courage and conflict

Addressing conflict sometimes takes courage. You may feel uncertain about how to address it and frightened that it will affect your relationship with the other person(s). There may be power dynamics involved. For example, you may need to address an issue with a person in a position of authority, such as a class professor or clinical instructor. Be courageous and act despite the fear, vulnerability, and uncertainty you may feel. It is better to be direct with the person you have a conflict with than to harbour resentment. Recognize this fear, vulnerability, and uncertainty. But also recognize the positive feelings associated with being courageous. You accomplish something important when you deal with conflict. You get courageous by being courageous.

One strategy to help you address the conflict is to write it down on a piece of paper and say it out loud. This can help you identify and acknowledge emotions attached to the conflict. Then when you address the conflict with the individual, you can focus on the issue and not the personal emotions which could impact the discussion. Ask to meet with the person and have a face-to-face discussion as opposed to trying to talk about the issue via email or text.

Case Example

Consider a situation in which a family is upset about the care their loved one is receiving, and tells you that after watching you do a patient transfer, you “clearly don’t know what you’re doing.”

Analysis

The family member’s words could cause a sense of threat for you. Perhaps you may fear a sense of being falsely accused and reported and are unsure of the consequences that might ensue. You may get very defensive and insist that you did “nothing wrong.” On the other hand, this family may be feeling a very different threat, i.e., perhaps they fear their loved one’s condition is deteriorating, and they may lose them soon. Any small error (or perceived error) in their loved one’s care may trigger fear around losing them. Having a conversation with the family to acknowledge the threat (i.e., fear) they are experiencing may be beneficial to resolving the conflict over their perception of your care.