11.1. Concepts: Circular Motion

Introduction

An object is in circular or rotational motion when it takes a circular path (such as the circumference of a circle). The angle of rotation is the angular equivalence of distance, and it is called the angular displacement.

The velocity of the object rotating is called the angular velocity. If the object rotates at a constant angular velocity, the motion will be called a uniform circular motion; if the object changes angular velocity during the rotation, the motion is called an accelerated circular motion.

In the case of an accelerated circular motion, the rate of change for the angular velocity is called the angular acceleration.

Concepts

11.1.1 Uniform circular motion

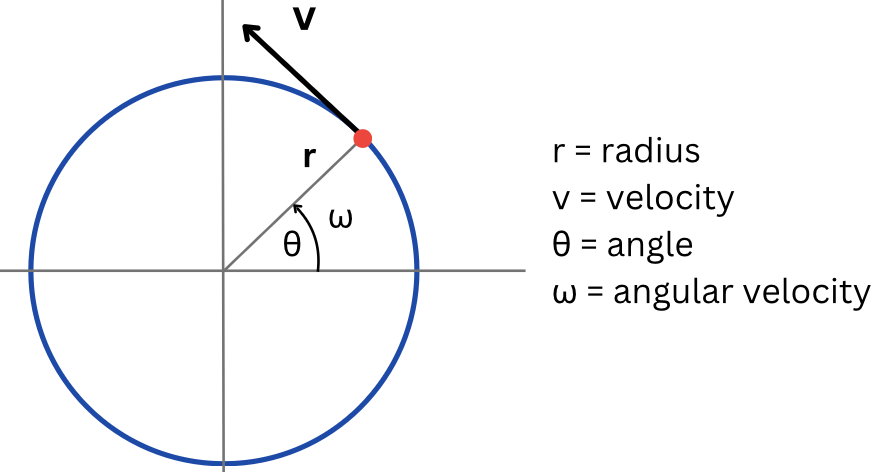

The angular displacement is represented by the angle travelled by the object undergoing the rotational motion (Figure 11.1):

The angular velocity represents the rate of change for the angle (Figure 11.1):

Combining equations (1) and (2) we find the formula that relates the tangential velocity to the angular velocity:

In the formulas and diagram above:

[latex]\theta[/latex] - represents the circular displacement in [latex]\text{[rad]}[/latex]

[latex]s[/latex] - represents the arc of the circle (circular distance traveled by the object) in

[latex]\text{[m]}[/latex]

[latex]r[/latex] - represents the radius of the circle in [latex]\text{[m]}[/latex]

[latex]\omega[/latex] - angular velocity in [latex]\text{[rad/s]}[/latex]

[latex]t[/latex] - the time elapsed in [latex]\text{[s]}[/latex]

[latex]v[/latex] - the linear or tangential velocity in [latex]\text{[m/s]}[/latex]

11.1.2 Tangential velocity. Centripetal acceleration

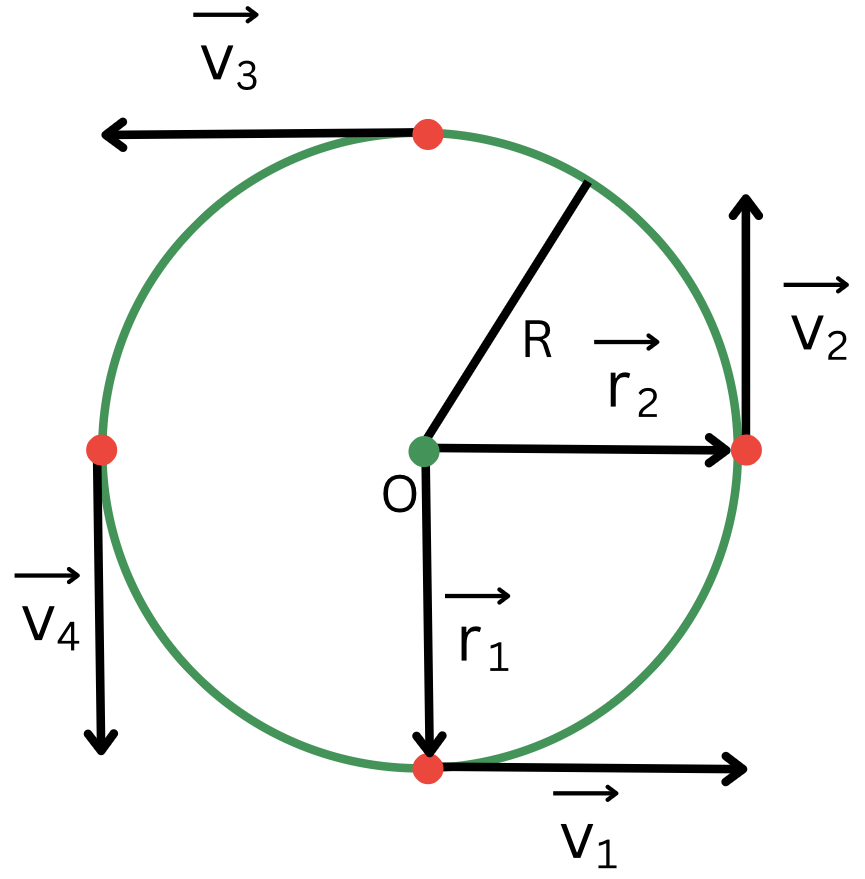

Speed is the magnitude of the velocity. And while the speed may be constant, the velocity is not. Since velocity is a vector with both magnitude and direction, we see that the direction of the velocity is always changing.

We call this velocity tangential velocity as its direction is tangent to the circle.

Therefore, linear acceleration, which is, by definition, the change in velocity divided by time, will not be zero.

Acceleration has the same direction as the change in velocity; in this case it points toward the centre of rotation. This is called the centripetal acceleration.

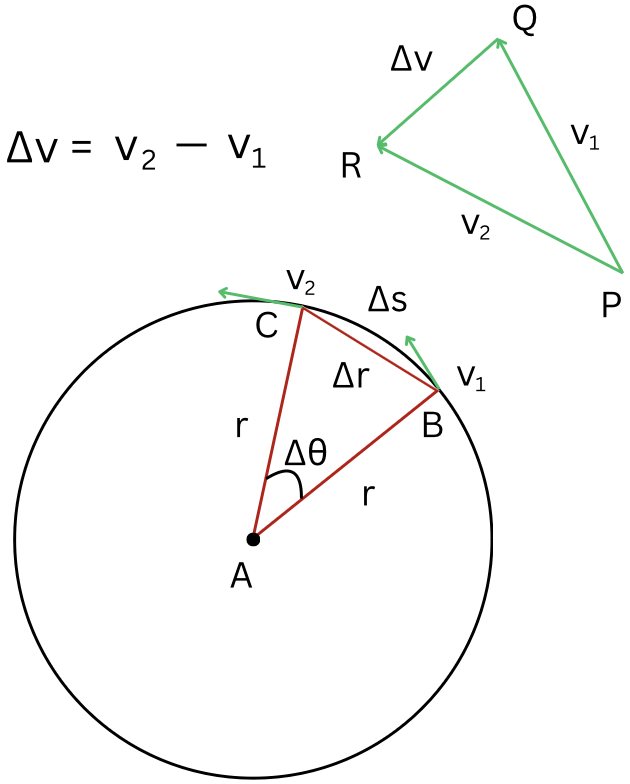

Using the properties of similar triangles (ABC and PQR, which are isosceles triangles), it can be derived that the centripetal acceleration is:

In the above formula:

[latex]a_c[/latex] - represents the centripetal acceleration (a linear acceleration directed towards the centre of the circle) in [latex][\text{m/s}^2][/latex]

[latex]v[/latex] - represents the linear velocity in [latex][\text{m/s}][/latex]

[latex]r[/latex] - represents the radius of the circle in [latex][\text{m}][/latex]

If we use formula (3) and substitute v for its expression in terms of [latex]\omega[/latex], then centripetal acceleration can also be expressed as:

In the above formula:

[latex]\omega[/latex] - represents the angular velocity in [latex][\text{rad/s}][/latex]

The centripetal acceleration is produced by a force (according to Newton’s second law). This force is called the centripetal force and can be calculated as:

Circular motion is also described by period and frequency.

Period represents the time to travel one complete circle and is measured in [latex]\text{[s]}[/latex].

Frequency represents the number of revolutions per unit of time and is measured in [latex]\text{[1/s] or [Hz]}[/latex].

The relationship between period and frequency is:

The relationship between angular velocity and period is:

It follows that:

11.1.3 Accelerated circular motion

When the angular velocity changes in time (either increasing or decreasing), the motion will be called an accelerated circular motion.

The angular acceleration represents the rate of change for the velocity:

In the above formula:

[latex]\alpha[/latex] - represents the angular acceleration in [latex][\text{rad/s}^2][/latex]

[latex]\Delta\omega[/latex] - represents the change in angular velocity in [latex][\text{rad/s}][/latex]

[latex]t[/latex] - time in which the velocity changed in [latex]\text{[s]}[/latex]

The formulas that describe the accelerated circular motion can be obtained by replacing the quantities of linear motion (such as displacement, velocity, and acceleration) by the quantities of circular motion (such as angular displacement, angular velocity and angular acceleration). This is shown in the table below:

| Linear motion | Circular motion |

|---|---|

| [latex]V_f = V_i + at[/latex] | [latex]\omega_f = \omega_i + \alpha t[/latex] |

| [latex]s = V_i t + \frac{1}{2} a t^2[/latex] | [latex]\theta = \omega_i t + \frac{1}{2} \alpha t^2[/latex] |

| [latex]s = \frac{V_i + V_f}{2} \times t[/latex] | [latex]\theta = \frac{\omega_i + \omega_f}{2} \times t[/latex] |

| [latex]V_f^2 = V_i^2 + 2as[/latex] | [latex]\omega_f^2 = \omega_i^2 + 2 \alpha \theta[/latex] |