10.3 Eugenics and Scientific Racism

Eugenics and Scientific Racism

Genetics has an ugly past – Eugenics. Eugenics is an inaccurate theory linked to historical and present-day forms of discrimination, racism, ableism and colonialism. It has persisted in policies and beliefs worldwide, including in Canada. Have we moved on, or are we just finding different ways to manifest the same thinking?

Hard Language

In the 21st century, we are accustomed to using vocabulary that is sensitive, respectful, and person-centered regarding physical and mental illnesses and challenges. The language used in the 19th and most of the 20th centuries was far more direct and judgmental. These terms enabled 19th and 20th-century reformers to objectify the individuals they were referring to. Understanding that relationship between language and reform is critical to understanding the attraction and authority of movements like eugenics. The language used in the original source material has been adapted to be more respectful.

The Big Picture:

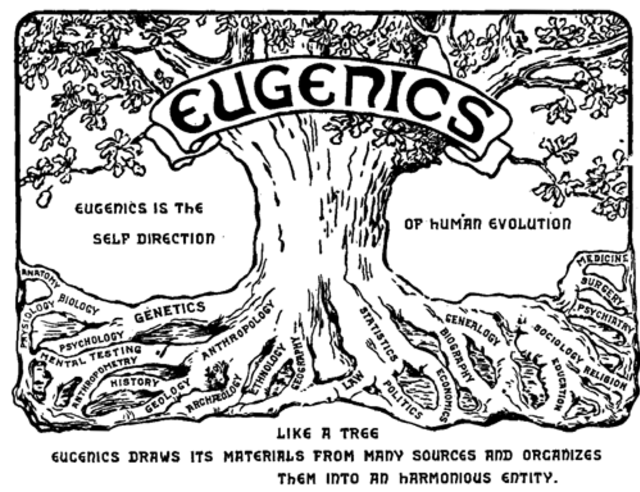

- Eugenics is the scientifically inaccurate theory that humans can be improved through selective breeding of populations.

- Eugenicists believed in a prejudiced and incorrect understanding of Mendelian genetics that claimed abstract human qualities (e.g., intelligence and social behaviours) were inherited in a simple fashion. Similarly, they believed complex diseases and disorders were solely the outcome of genetic inheritance.

- The implementation of eugenics practices has caused widespread harm, particularly to populations that are being marginalized.

- Eugenics is not a fringe movement. Starting in the late 1800s, leaders and intellectuals worldwide perpetuated eugenic beliefs and policies based on common racist and xenophobic attitudes. Many of these beliefs and policies still exist.

- The genomics communities continue to work to scientifically debunk eugenic myths and combat modern-day manifestations of eugenics and scientific racism, particularly as they affect Black, Indigenous, and people of colour, people with disabilities, and LGBTQAI2+ individuals.

Visit the NHGRI website – Eugenics: Its Origin and Development (1883-Present). Scroll down to the timeline and use the navigation arrows to learn about some of the more predominant historical examples of eugenics.

What are eugenics and scientific racism?

Eugenics is the scientifically erroneous and immoral theory of “racial improvement” and “planned breeding,” which gained popularity during the early 20th century. Eugenicists worldwide believed that they could perfect human beings and eliminate so-called social ills through genetics and heredity. They thought the use of methods such as involuntary sterilization, segregation and social exclusion would rid society of individuals deemed by them to be unfit.

Eugenics can be separated into two equally erroneous categories. Negative eugenics is described above (NIH, 2022). Positive eugenics is the encouragement of reproduction among genetically advantaged people (Thomas et al., 2016). It should be noted that the characteristics that were deemed to be more or less desirable were not determined by genes at all. These were entirely social constructs. Associating these beliefs with science distorts the evidence and undermines the credibility and validity of the findings.

Scientific racism is a practice that appropriates the methods and legitimacy of science to argue for the superiority of one race over another. Like eugenics, scientific racism grew out of:

- the misappropriation of revolutionary advances in medicine, anatomy and statistics during the 18th and 19th centuries.

- Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution through the mechanism of natural selection.

- Gregor Mendel’s laws of inheritance.

Eugenic theories and scientific racism drew support from contemporary xenophobia, antisemitism, sexism, colonialism and imperialism, as well as justifications for slavery.

How did eugenics begin?

Listen:

Genetics Unzipped is a great podcast that covers a vast array of topics in genomics. Listen to Living with the Eugenic Past: Michele Goodwin (17:36). This is one of several talks on the subject from the conference titled the same. Michele Goodwin is a Professor of Law at the Centre for Biotechnology, Global Health Policy Director at the University of California Irvine, and a senior lecturer at Harvard Medical School.

“Her talk focused on how the long shadow of eugenics and white supremacy persists into the present day and remains embedded in contemporary political frameworks, and why this pernicious ideology is taking so long to die” (The Genetics Society, 2022).

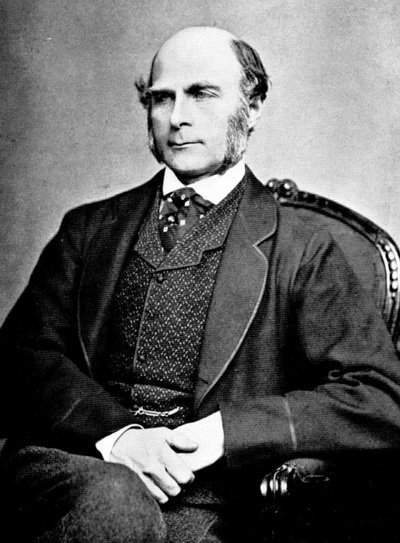

Galton defined eugenics as “the study of agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations either physically or mentally.” Galton claimed that health, disease, and social and intellectual characteristics were based upon heredity and the concept of race.

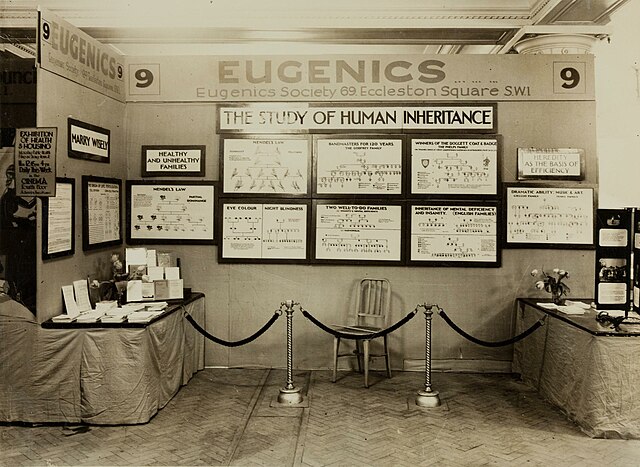

During the 1870s and 1880s, discussions of “human improvement” and the ideology of scientific racism became increasingly common. So-called experts determined individuals and groups to be superior or inferior. They believed biological and behavioural characteristics were fixed and unchangeable, placing individuals, populations and nations inside that hierarchy.

What did eugenics look like across the globe?

By the 1920s, eugenics had become a global movement. There was popular, elite and governmental support for eugenics in Germany, the United States, Great Britain, Italy, Mexico, Canada and other countries. Statisticians, economists, anthropologists, sociologists, social reformers, geneticists, public health officials and members of the general public supported eugenics through various academic and popular literature.

The most well-known application of eugenics occurred in Nazi Germany in the lead-up to World War II and the Holocaust. Nazis in Germany, Austria and other occupied territories euthanized at least 70,000 adults and 5,200 children. They implemented a campaign of forced sterilization that claimed at least 400,000 victims. This culminated in the near destruction of the Jewish people, as well as an effort to eliminate other marginalized ethnic minorities, such as the Sinti and Roma, individuals with disabilities and LGBTQ+ people.

Slavery and its legacies, fears of “miscegenation,” and eugenics were deeply connected in the early 20th century. Prominent American eugenicists expounded on their concerns of “race suicide,” or the increasingly differential birthrates between immigrants and non-Nordic races compared to native-born Nordic whites. Eugenicists used these concerns to promote discriminatory policies like anti-immigration and sterilization.

American eugenicists from a variety of disciplines declared specific individuals unfit or anti-social, which resulted in the involuntary sterilization of at least 60,000 people through 30 states’ laws by the 1970s.

These eugenicists disproportionately targeted non-white people, particularly those with lower socio-economic status, and people with disabilities during the entirety of the 20th century. Eugenicists were also crucial to the enactment of discriminatory immigration legislation that was passed in 1924 (the Johnson-Reed Act), which completely excluded immigrants from Asia.

Was there eugenics in Canada?

The Eugenic Archive has a wealth of historical information in an accessible format. Check out this interactive timeline of Eugenics in Canada

The eugenicist strategy has been one of selective breeding, but that term does not do it justice. “Selective breeding” invariably involves selecting in: that is, encouraging people who were deemed to possess more desirable qualities to have a significant number of children. However, the eugenics message in Canada was more about selecting out: to find ways to deter the reproduction of what they regarded as fated populations doomed by their genes to imperil themselves, successive generations, and the nation.

Canada sterilized proportionately fewer people than the United States — the total number is believed to be slightly more than 3,000 – but record keeping was inconsistent and there is little doubt that an accurate total is unknowable (Hanson and Kind, 2013).

Listen:

Judy Lytton is a eugenics survivor and currently is on the Board for the Living Archives in Eugenics in Western Canada. Hear her story.

Concept in Action

The eugenics movement in Western Canada and the application of sterilization are discussed by historian of institutionalization Megan Davies (York University).

Watch Dr. Megan J. Davies Question 9 – Eugenics (5 mins) on YouTube

Video source: TRU Open Learning. (2015, November 17). Dr. Megan J. Davies question 9 – eugenics. https://youtu.be/1rzLfGfcwMg

Do eugenics and scientific racism still exist?

While eugenics movements especially flourished during the three decades before the end of World War II, eugenics practices such as involuntary sterilization, forced institutionalization, social ostracization, and stigma were common in many parts of Canada until at least the 1970s and, in some instances, have continued into the present in various forms. Historical injustices also lead people to fear and mistrust government bodies.

Watch Kyle Lillo describe his concerns about having children. He fears that due to his disability, the government will apprehend his children and deem him unfit to parent.

Compulsory Sterilization in Canada

Compulsory sterilization in Canada is an ongoing practice that has a documented history in the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia. Sixty Indigenous women in Saskatchewan sued the provincial government, claiming they had been forced to accept sterilization before seeing their newborn babies (Moran, 2016). In June 2021, the Standing Committee on Human Rights in Canada found that compulsory sterilization is ongoing in Canada, and its extent has been underestimated (Government of Canada, 2022). A bill was introduced to Parliament in 2024 to end the practice (Ryckewaert, 2024).

Over 9,000 Indigenous People in British Columbia were surveyed and interviewed in an inquiry into racism and discrimination in BC’s healthcare system. The In Plain Sight Report summarized the findings, which included examples of forced sterilization of Indigenous women in Canada.

With the completion of the Human Genome Project (HGP) and, more recently, advances in genomic screening technologies, there is some concern about whether generating an increasing amount of genomic information in the prenatal setting would lead to new societal pressures to terminate pregnancies where the fetus is at heightened risk for genetic disorders, such as Down Syndrome and spina bifida.

The possible genomic-based screening of embryos for behavioural, psychosocial and intellectual traits would be reminiscent of the history of eugenics in its attempt to eliminate specific individuals.

In fact, some geneticists view both genomic screening and genetic counselling as an extension of eugenics.

Human enhancement through consensual gene editing has also been described as the new eugenics. Despite its basis in science and being consensual, it has underpinnings of the historical examples of eugenics – the pursuit of a superior being at the expense of those considered inferior.

How can nurses address eugenics and scientific racism?

Nurses can commit to interrogating the legacies of eugenics and scientific racism to further develop ethical and equitable uses of genomics. Understanding the history of eugenics, including forced sterilizations and discriminatory practices, helps healthcare providers recognize the deep-seated mistrust some patients may have toward medical institutions. This awareness can guide providers in delivering trauma-informed care. By integrating these practices, healthcare providers can create a safer, more supportive environment for all patients, particularly those who have experienced trauma. This history emphasizes the potential for misuse of genetic information and reinforces the need for nurses to remain vigilant against discrimination and stigmatization based on genetic traits. Nurses can integrate this knowledge and awareness into practice to ensure genomic services are provided ethically, equitably, and inclusively.

It is also crucial that nurses critically evaluate medical literature to identify scientific racism, and challenge unscientific medical practices such as the misrepresentation of race as a biological variable rather than a social construct.

Read:

Dordunoo, D., Abernethy, P., Kayuni, J., McConkey, S., & Aviles-G, M. L. (2022). Dismantling “race” in health research. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 54(3), 239-245. https://doi.org/10.1177/08445621221074849

Questions for Reflection

- What can nurses do to avoid making assumptions about their patients based on skin colour or perceived racial background?

- How can nurses identify and address the impacts of racism, including frequency, intensity, and duration of racist encounters in their patients’ lives when assessing their health and planning their care?

- Why do the authors propose using the term racism instead of race as a variable in health research and practice and how would this help quantify the social determinants of health that are related to racism?

Attribution & References

Except where otherwise noted, this page is adapted from

- Eugenics and Scientific Racism: Fact Sheet courtesy of National Human Genome Research Institute, Public domain with attribution

- 7.8 Eugenics In Canadian History: Post-Confederation by John Douglas Belshaw, CC BY 4.0 International License

- First paragraph under Compulsory Sterilization in Canada is reused from Compulsory sterilization in Canada In Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0

- How can nurses address eugenics and scientific racism? Written by Andrea Gretchev is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 International License

References

Government of Canada, Public Services and Procurement Canada, Integrated Services Branch, Government Information Services, Publishing and Depository Services. (2022, July). The scars that we carry : forced and coerced sterilization of persons in Canada. Part II / Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights ; the Honourable Salma Ataullahjan, chair, the Honourable Wanda Thomas Bernard, deputy chair.: YC32-0/441-4E-PDF – Government of Canada Publications – Canada.ca. https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.913511/publication.html

McLaren, A. (1990). Our own master race: Eugenics in Canada, 1885-1945. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart.

Moran, P. (2016, January 15). Indigenous women kept from seeing their newborn babies until agreeing to sterilization, says lawyer. CBC Radio. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-november-13-2018-1.4902679/indigenous-women-kept-from-seeing-their-newborn-babies-until-agreeing-to-sterilization-says-lawyer-1.49026934

NIH. (May 18, 2022). Eugenics and scientific racism. https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/Eugenics-and-Scientific-Racism

The Genetics Society. (2022, November 27). Living with the eugenic past: Michele Goodwin. Genetics Unzipped: The Genetics Society Podcast. https://geneticsunzipped.com/blog/2022/11/27/adelphi-genetics-michele-goodwin?rq=living%20with%20the%20eugenic

Ryckewaert, L. (2024, March 25). Senate bill seeking to criminalize forced sterilizations raises concerns over unintended consequences. The Hill Times.https://www.hilltimes.com/story/2024/03/25/senate-bill-seeking-to-criminalize-forced-sterilizations-raises-concerns-over-unintended-consequences/415997/

Thomas, G. M. & Katz Rothman, B. (2016). Keeping the backdoor of eugenics ajar: Disability and future prenatal screening. AMA Journal of Ethics, 18(4), 406-415. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/keeping-backdoor-eugenics-ajar-disability-and-future-prenatal-screening/2016-04