8 Respiratory Diseases of Horses

| Course priority #1 | Course priority #2 | Course priority #3 | |

| Horses |

|

|

|

equine respiratory viral infections

Common viral infections in Ontario include:

- Equine herpesviruses-1 and 4 (Equine viral rhinotracheitis)

- Equine influenza (currently due to A/equi 2 = H3N8, formerly due to A/equi 1 = H7N7)

- Equine rhinitis viruses

- (Equine viral arteritis, but this is rare in Ontario)

These viruses are common causes of upper respiratory illness. In addition, both equine herpesvirus-1 or -4 and equine influenza can cause pneumonia, which may prove fatal if secondary bacterial pneumonia develops.

Equine herpesvirus-1 is an important cause of abortion and of neonatal illness due to systemic viral infection.

EHV-1, especially certain “neuropathic” strains, can cause serious outbreaks of encephalitis.

The clinical diagnosis of viral infection is usually based on detecting viral nucleic acid by PCR testing of nasal swabs. An alternative is to demonstrate rising antibody titres in paired serum samples, taken from the same animal 3 weeks apart.

Strangles

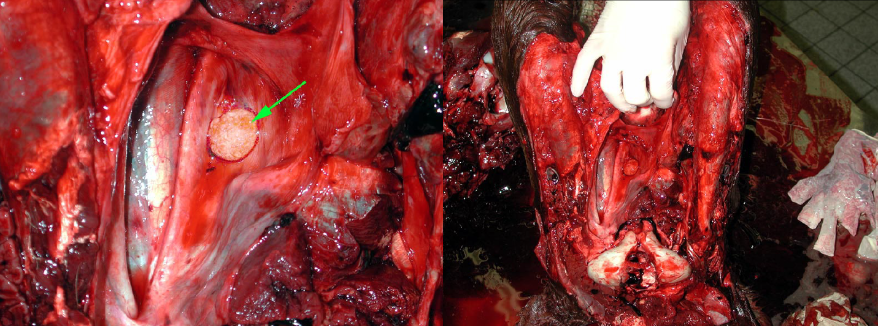

Strangles is caused by Streptococcus equi ssp. equi. Infection is by inhalation or ingestion, and the bacterium colonizes the mucosa of the nasopharynx and guttural pouch, then spreads to local lymph nodes. Affected horses have mucopurulent nasal discharge, swollen retropharyngeal and submandibular lymph nodes, and fever. The lymph nodes eventually rupture and drain pus, which is highly infectious to other horses.

Gross lesions include mucopurulent rhinitis and suppurative lymphadenitis with abscessation.

Sequelae are important in this disease:

- Bacterial bronchopneumonia due to aspiration of exudate from the nasopharynx

- Guttural pouch empyema

- “Bastard strangles” refers to hematogenous spread of infection to colonize lymph nodes and result in abscesses. Abscesses of the abdominal (mesenteric) lymph nodes are particularly consequential and may cause colic.

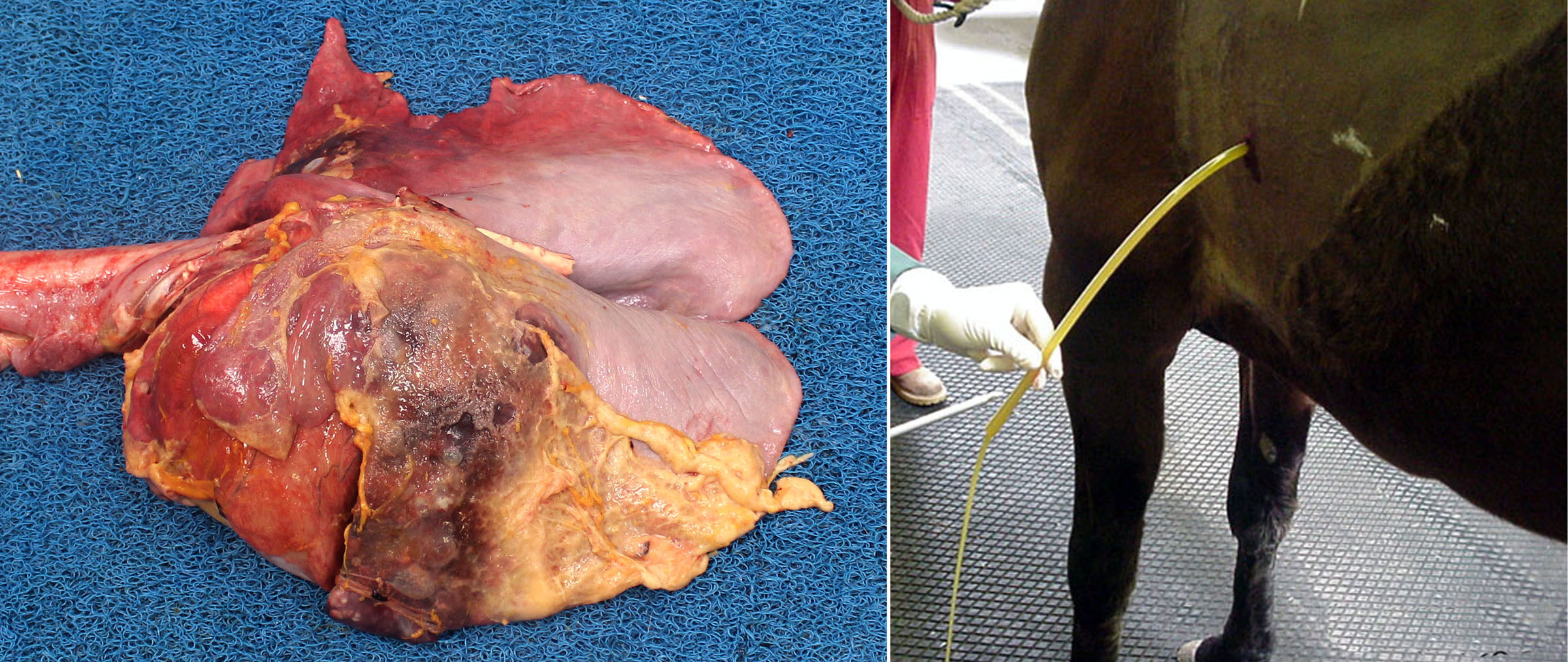

- Purpura hemorrhagica refers to systemic immune-complex-mediated vasculitis. This manifests as disseminated hemorrhages and edema in the skin of the distal limbs.

Question:

Bastard strangles vs. purpura hemorrhagica: which of these is a consequence of bacteremia, and which is an immune complex-mediated disease? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Guttural pouch mycosis

Aspergillus sp. causes a unilateral plaque of fungal hyphae covering a fibrinonecrotic and ulcerative lesion, within the guttural pouch. The fungal plaque causes inflammation and necrosis of anatomically important structures in the guttural pouch:

- Internal carotid artery → epistaxis

- Vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves → dysphagia

- Sympathetic ganglion or nerve → Horner’s syndrome

- Laryngeal nerve→ laryngeal paralysis

Question:

What is the gross appearance of guttural pouch mycosis? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

List 2 clinically serious sequelae to mycosis of the guttural pouch in horses. (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Severe equine asthma: Heaves

Archaic names: recurrent airway obstruction, small airway disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc.

Asthma in horses has similarities to human asthma: it causes episodes of inflammation that result in obstruction of the small airways. This results in clinical signs of respiratory distress and cough. Asthma is a hypersensitivity reaction to inhaled substances in dusty or mouldy feed. Typically, asthma is not a continuous disease, but instead causes episodes of clinical signs separated by periods of normality. Although asthma is undoubtedly a hypersensitivity, it seems not to be an allergy mediated by IgE and mast cells (although there is controversy on this point).

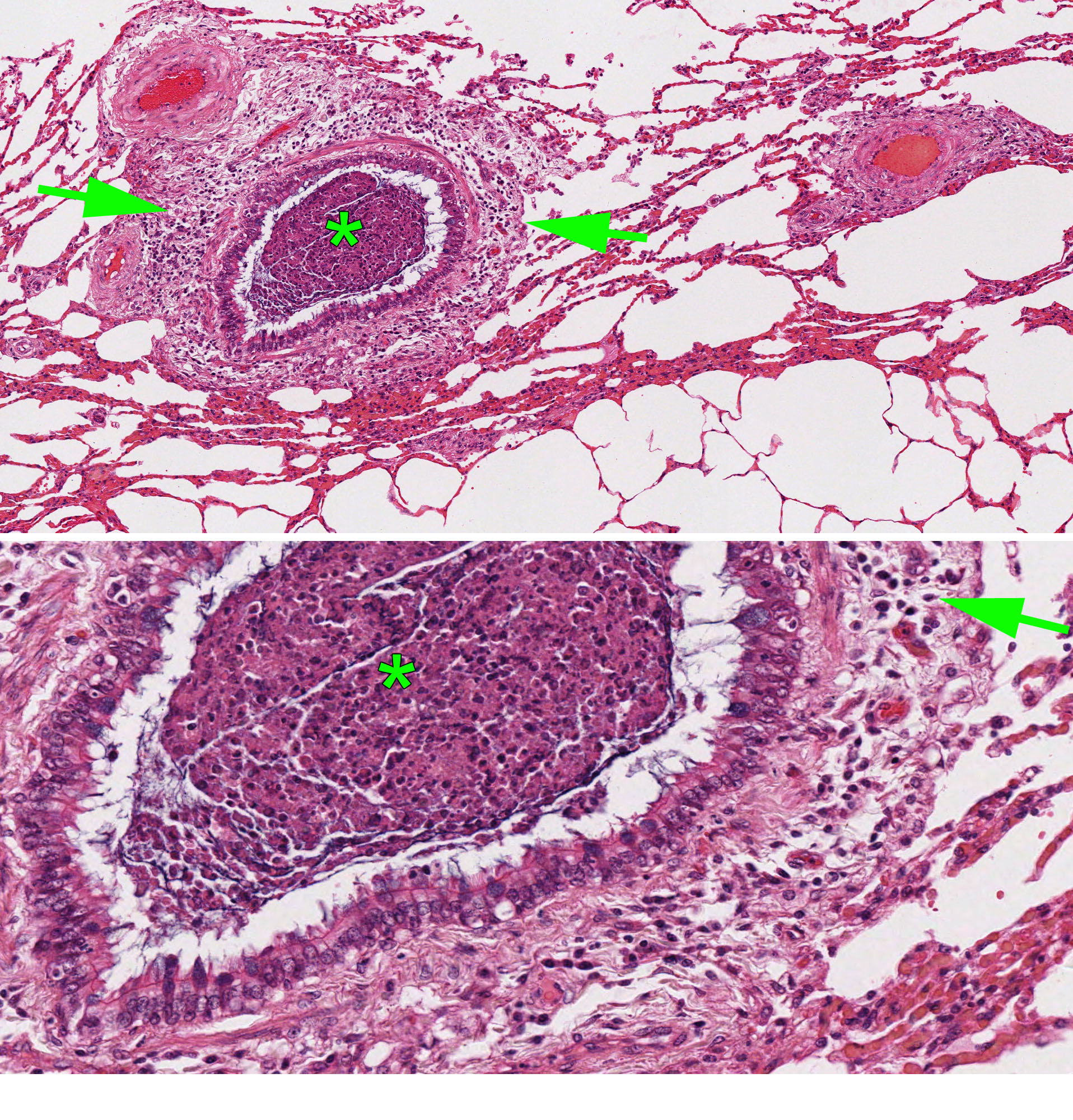

The histologic lesions target the bronchioles and include:

- Neutrophils and mucus filling the lumen of the bronchioles

- Lymphocytes and neutrophils in the walls of bronchioles

- Hypertrophy of bronchiolar smooth muscle

- Goblet cells, which are normally present only in the larger airways, are present in the small bronchioles (mucous metaplasia)

Consider the reasons for airway obstruction in horses with heaves, in light of how you would manage this clinically. Airway obstruction in this disease is due to bronchoconstriction, the presence of mucus and neutrophils in the lumen, and thickening of the bronchiolar mucosa by the inflammatory response. Inflammation triggers all of these responses—bronchoconstriction, mucus hypersecretion, leukocyte infiltration, and mucosal edema—so inhaled corticosteroids are a mainstay of therapy. Bronchodilators may be helpful in relieving the smooth muscle contraction that leads to bronchoconstriction. And mucinolytics might be used, although evidence of their effectiveness is lacking. Thus, asthma is a nice context for considering the functional effects and clinical manifestations of airway-centered inflammation.

Question:

What anatomic structure is targetted by the lesions of heaves (severe equine asthma)? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

What are 3 mechanisms of airway obstruction in heaves? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Rhodococcus equi

Rhodococcus equi is a gram-positive bacterium present in soil. Disease is more common on farms with heavy Rhodococcus equi contamination of the soil, and where foals are kept in dusty paddocks. It is a facultative intracellular pathogen that survives within macrophages, similar to mycobacteria to which Rhodococcus is closely related. This is of clinical importance because many antibiotics are not effective against intracellular bacteria.

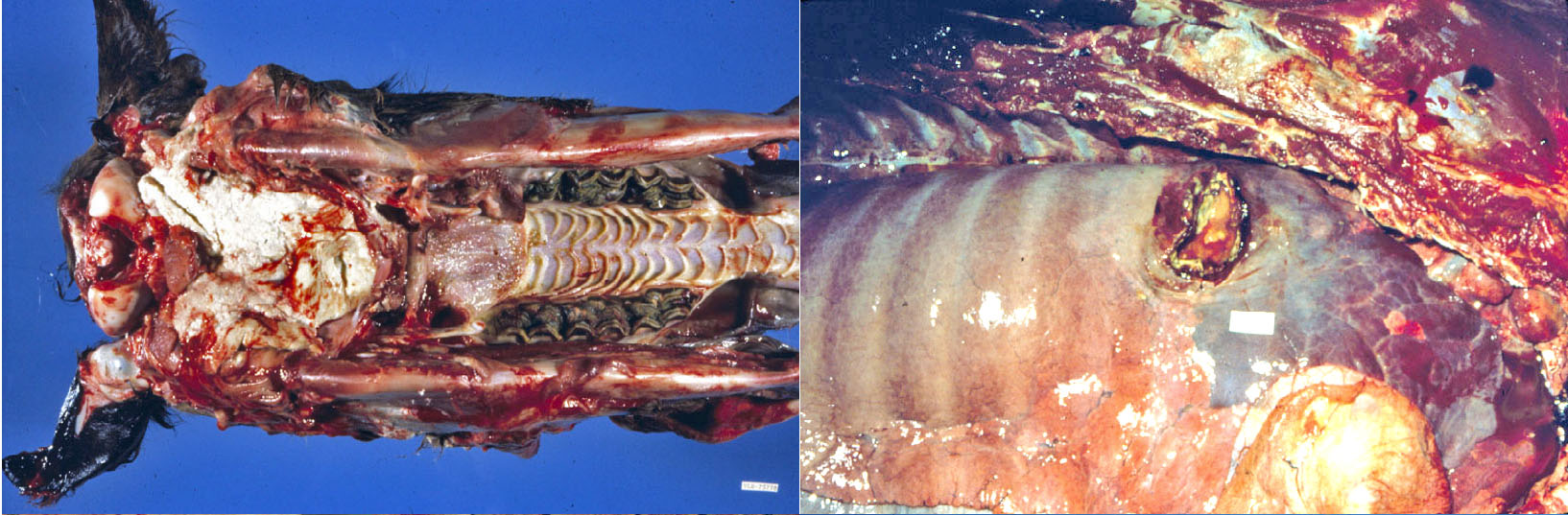

The infection causes enzootic or sporadic disease, and occasional outbreaks, affecting 2-6-month-old foals. The infection and the lesions are always chronic, but clinical signs may be either acute or chronic.

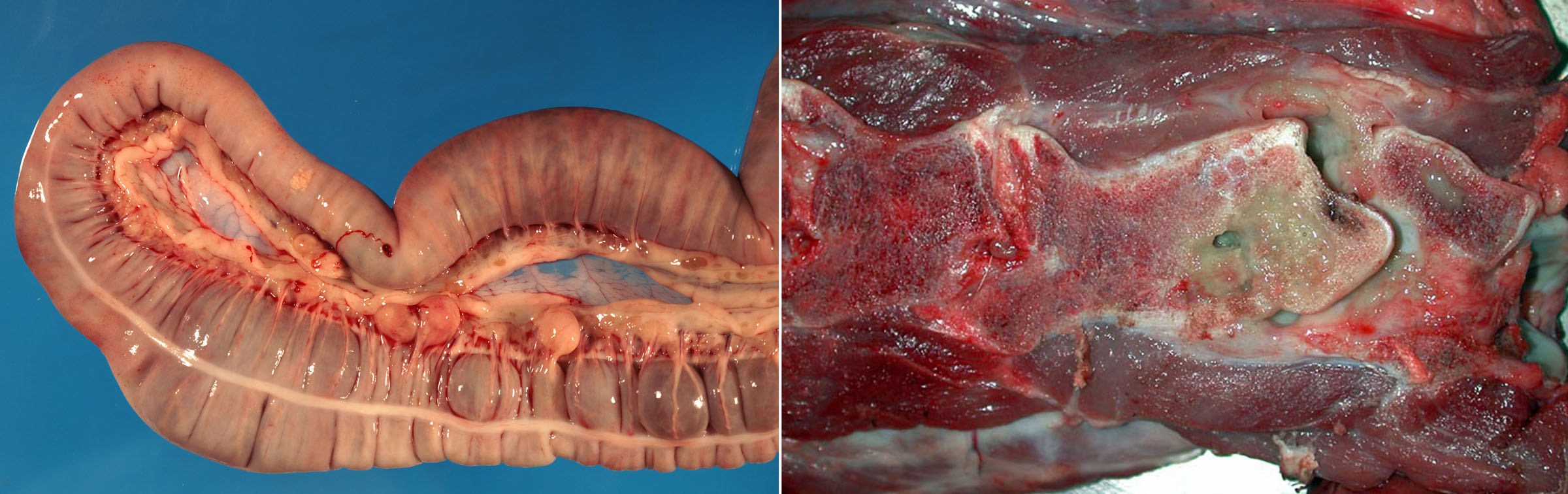

The respiratory form (due to inhalation of bacteria) is most common, with coughing, depression, fever, and weight loss. Other forms that may occur with or without respiratory disease include a colonic form causing diarrhea (due to ingestion of bacteria from the environment, or expectoration of bacteria from the lungs), or polyarthritis causing lameness and swollen joints. The colonic form consists of abscesses in colonic lymph nodes and sometimes colonic ulcers.

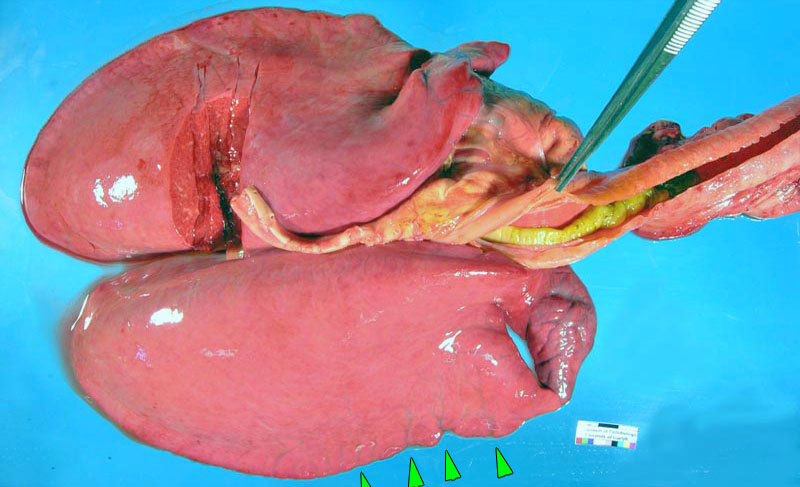

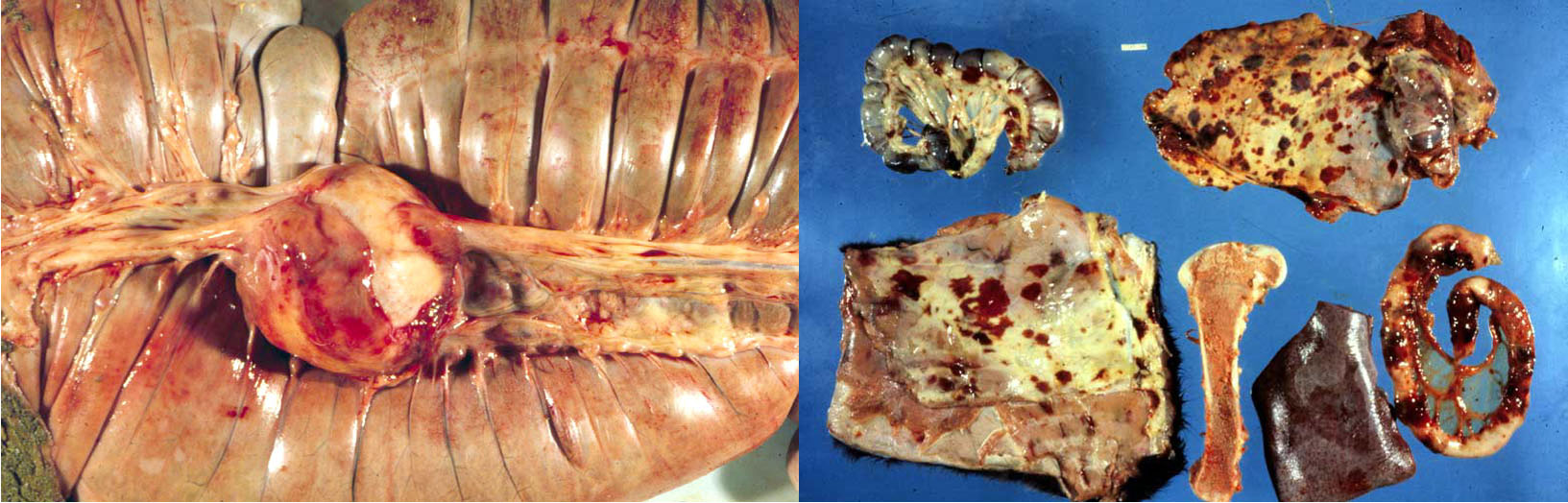

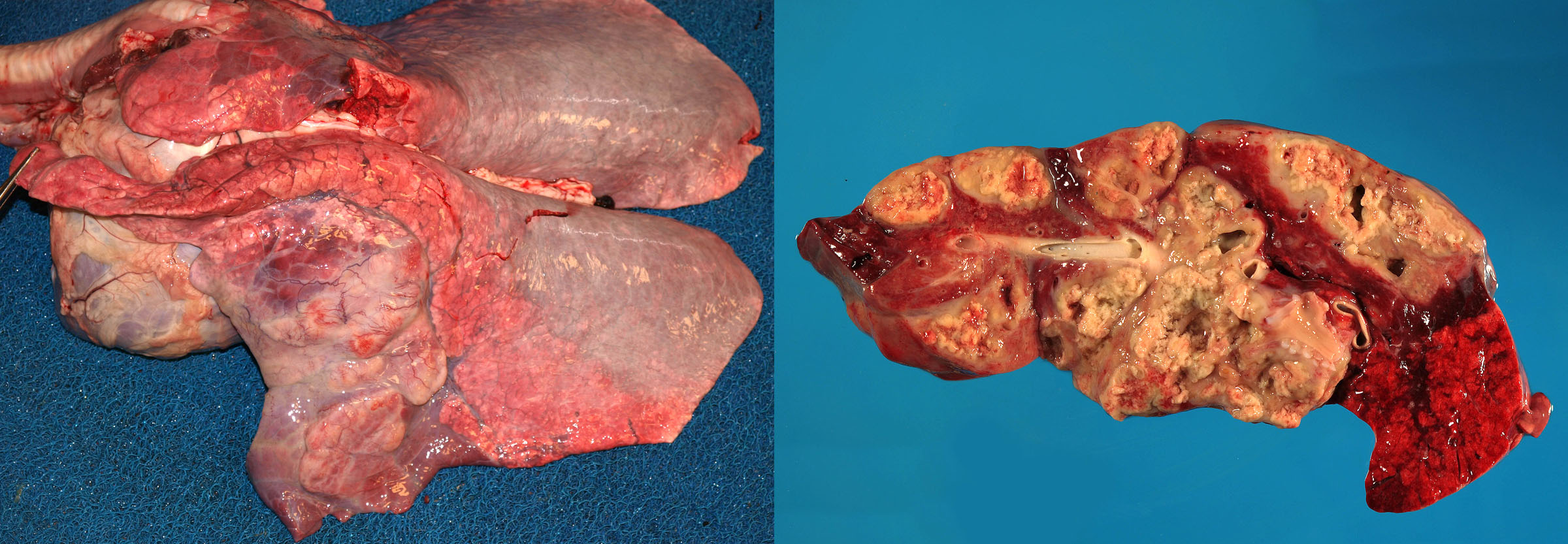

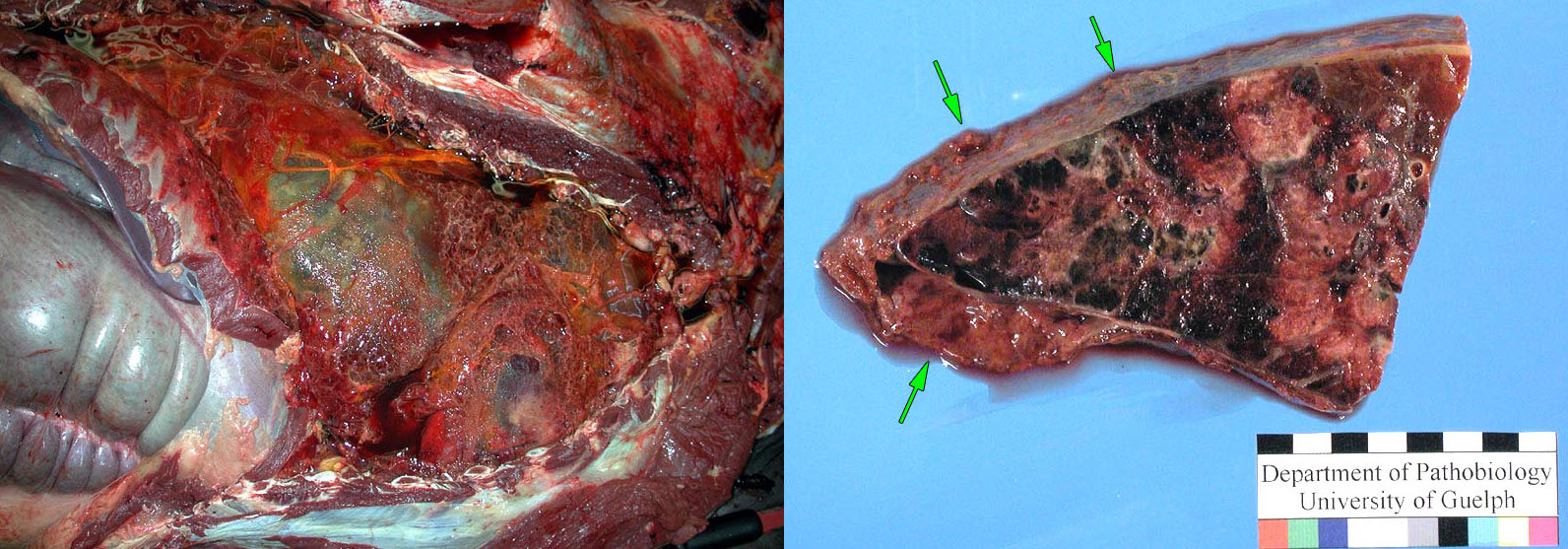

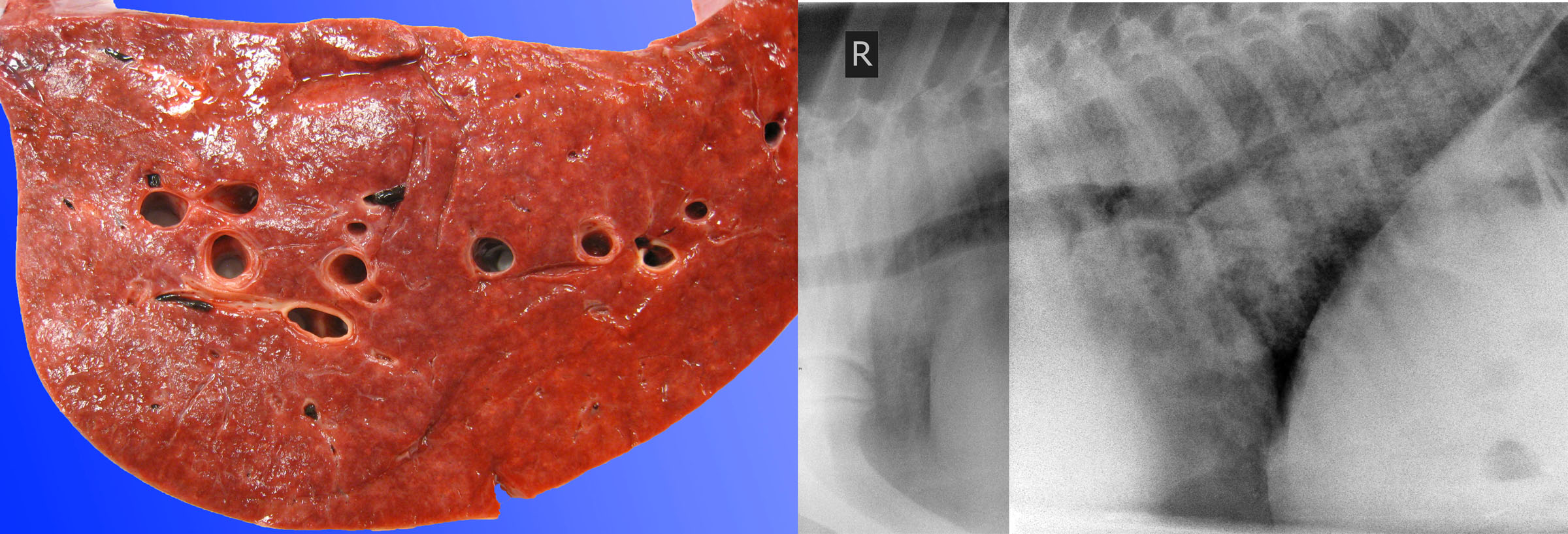

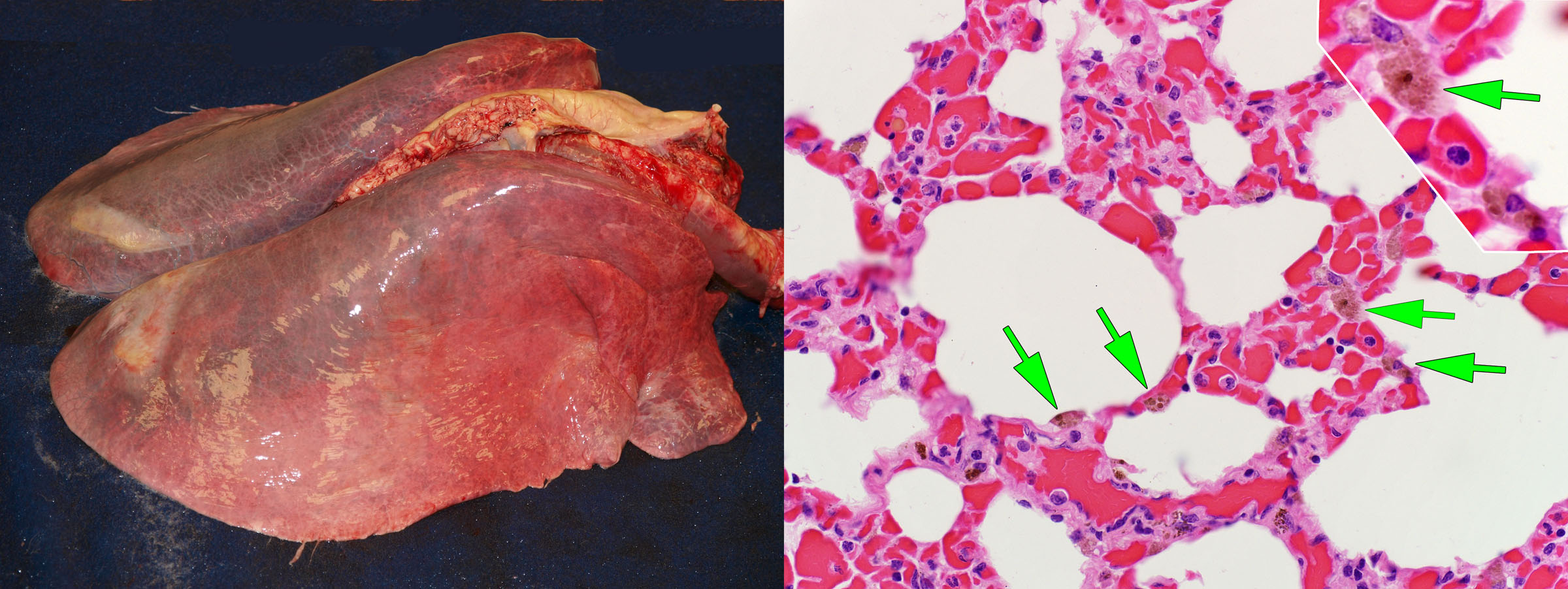

Because the bacteria are not highly toxigenic, lung lesions are often very extensive before clinical signs become apparent. This is always a chronic disease, even if the clinical presentation is acute. Grossly, the lung lesions usually have a cranioventral pattern of consolidation, and these consolidated lesions contain multifocal pyogranulomas that develop into abscesses. Mild cases may have multifocal pyogranulomas or abscesses without consolidation of adjacent lung tissue. Bronchial lymph nodes also contain pyogranulomas or abscesses.

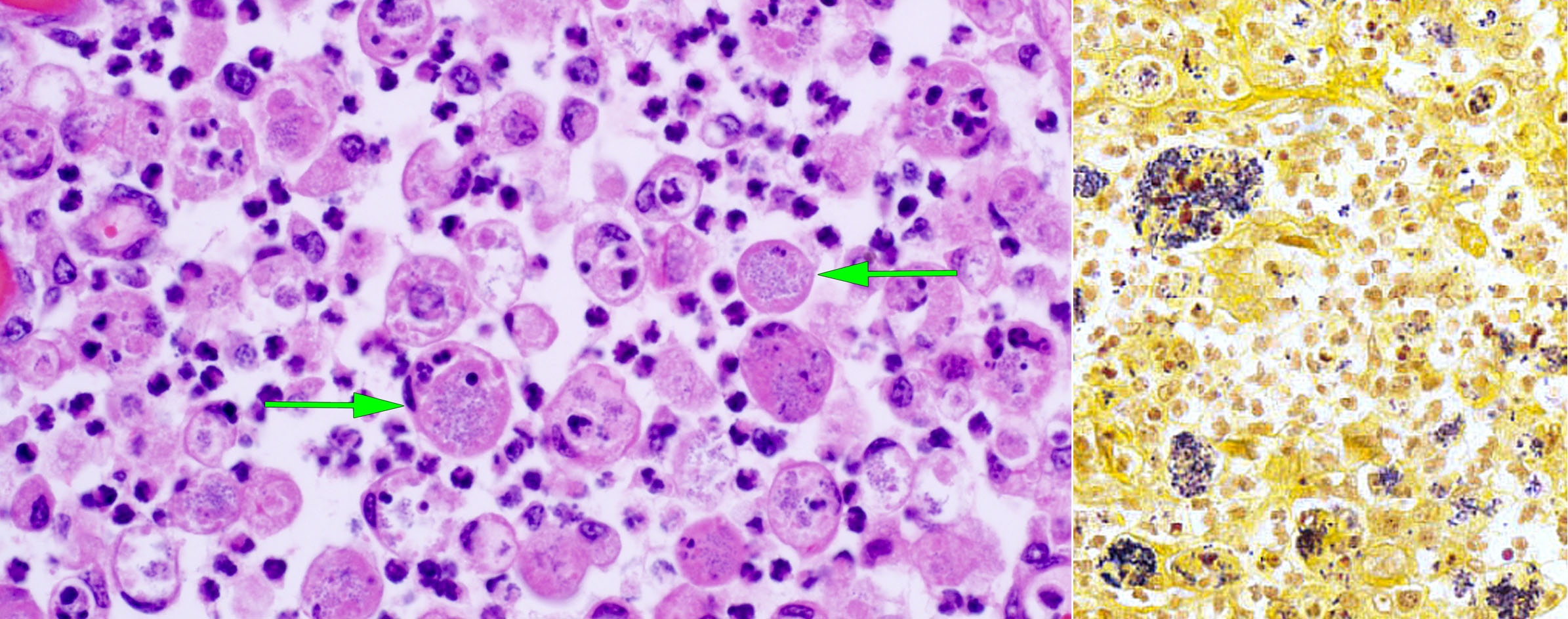

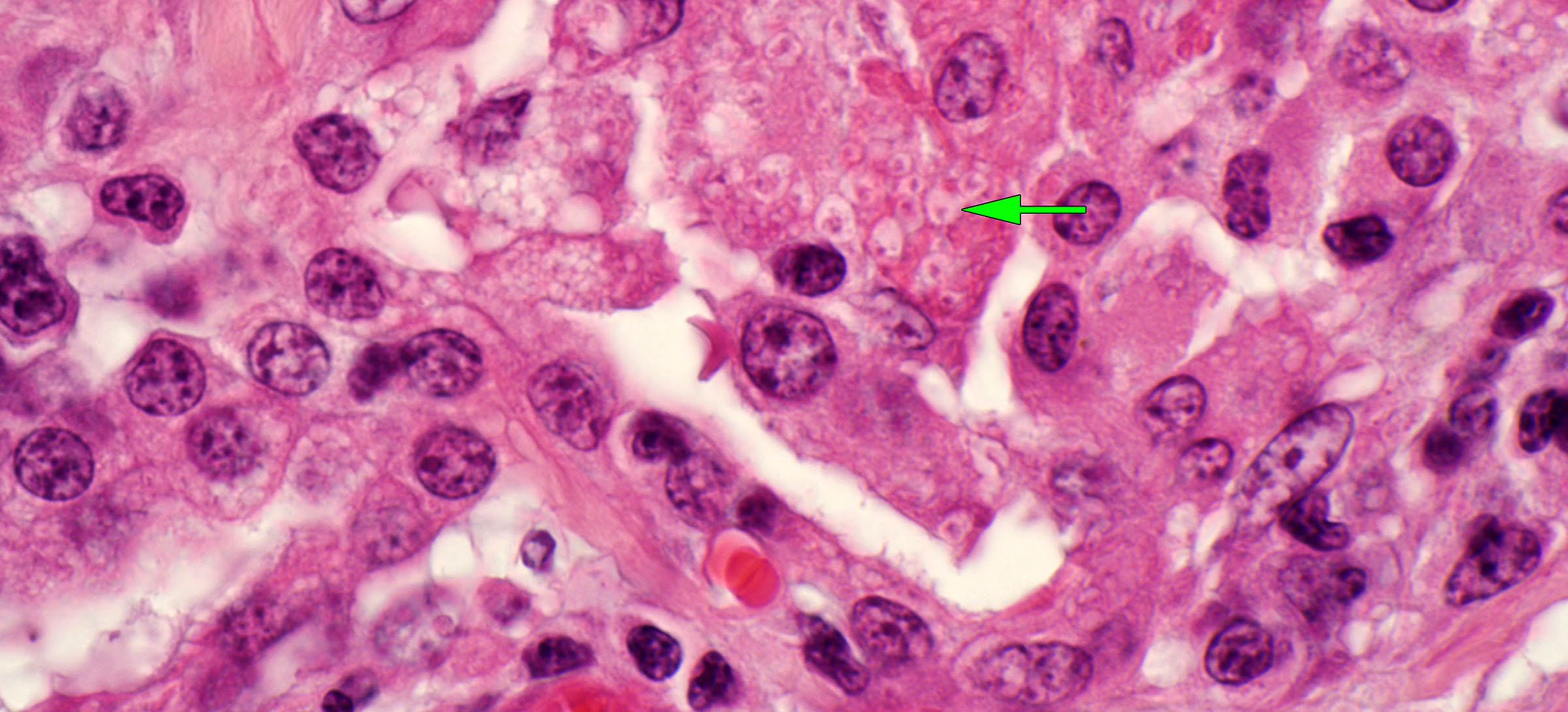

Histologic findings are infiltrates of neutrophils and macrophages in alveoli and bronchioles. These often contain multinucleated giant cells, and some macrophages contain innumerable intracytoplasmic Gram-positive bacteria.

The diagnosis is confirmed by bacterial culture of fresh or frozen lung tissue, taken from the most severely affected area of lung.

Question:

Describe the expected gross lesions of Rhodococcus equi infection of the respiratory tract. (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

Why is Rhodococcus pneumonia resistant to many antibiotics that are effective for other forms of pneumonia in horses? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

In Rhodococcus infection, what are the two pathogeneses of the lesions in the colonic lymph nodes? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Pleuropneumonia

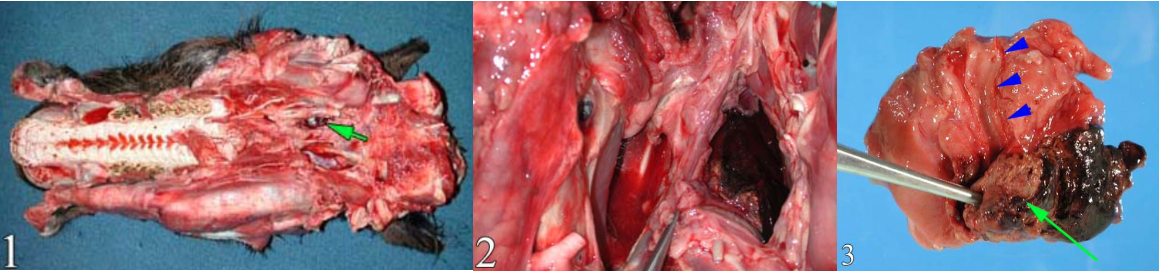

Pleuritis affects mature horses—often young adults—especially following transportation. Most cases have an underlying bronchopneumonia, with pleuritis developing as bacteria migrate into the pleural space. Many cases represent aspiration pneumonia that develops when horses are transported with their heads held up. The resulting clinical signs include fever, variable dyspnea, depression and anorexia, and muffled or absent heart and lung sounds.

Grossly, the pleuritis is characterized by abundant, often foul-smelling, cloudy fluid with fibrin clots and/or fibrous adhesions. The pleural exudate is so overwhelming that it is easy to overlook the underlying lung lesion. However, careful inspection usually reveals a localized area of bronchopneumonia that is firm, deep red, and may have areas of necrosis.

Question:

How does the pathogenesis of fibrinous pleuritis in a feedlot calf differ from that in a racehorse? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

interstitial (BRONCHOINTERSTITIAL) pneumonia of foals

This is a somewhat common cause of acutely fatal respiratory disease in 2-8-month-old foals. The cause is unknown. Suggested causes are an unidentified viral infection, hyperthermia caused by erythromycin therapy for Rhodococcus, or an aberrant inflammatory response to Rhodococcus infection. Some cases have concurrent but mild lesions of Rhodococcus equi pneumonia.

The disease is sporadic, or rarely affects multiple foals. It is characterized by an acute onset of severe dyspnea, and poor response to therapy.

Grossly, the lungs are diffusely firm with rubbery texture. Histologic lesions are bronchiolar necrosis, hyaline membranes, and/or proliferation of alveolar type II pneumocytes. The diagnosis is based on the gross and histologic lesions. Attempts to isolate viruses have been inconsistent and mostly futile.

Question:

In 2–8-month-old foals with interstitial (bronchointerstitial) pneumonia, what is the gross appearance of the lung? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

In 2–8-month-old foals with interstitial (bronchointerstitial) pneumonia, what is the common concurrent disease? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Pneumocystis carinii

An uncommon cause of interstitial pneumonia in foals, thought to be always secondary to immunosuppression.

Equine adenovirus

Fatal pneumonia in immunosuppressed foals, such as Arabian foals, with combined immunodeficiency. The diagnosis is based on histologic identification of the characteristic inclusion bodies.

Hyaline membrane disease

(aka Neonatal equine respiratory distress syndrome “NERDS”)

Premature foals have immature type II pneumocytes, and these cells have not matured enough to produce adequate surfactant. This results in increased surfacant tension within the lung, atelectasis because the alveoli can’t inflate. Furthermore, because of abnormal pressures on the alveolar surface, physical damage to type I pneumocytes leads to formation of hyaline membranes. Affected foals are dyspneic, hypoxemic, and sometimes have secondary cerebral injury due to hypoxemia. Differential diagnoses for interstitial lung disease in neonatal foals include meconium aspiration syndrome, equine herpesvirus-1 infection, and septicemia. In contrast, the above-described condition (interstitial / bronchointerstitial pneumonia of foals) occurs in 2–8-month old animals.

Septicemia in neonatal foals

A variety of Gram-negative bacteria cause septicemia in foals: Actinobacillus equuli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, E. coli, and others.

It is important to search for predisposing causes, such as inadequate intake of colostrum, concurrent diseases including bronchopneumonia, chilling, or dirty environments.

The acute lesions may be surprisingly subtle at necropsy. The lungs are diffusely edematous and may be firm, and there may be pinpoint white foci in lungs, kidneys, and other tissues. Lesions are more florid in other cases, with fibrinous exudates in body cavities.

Equine herpesvirus

EHV-1 is an important cause of diffuse interstitial lung disease in neonatal foals. It is discussed above with upper respiratory disease.

Meconium aspiration syndrome

Aspiration of meconium by a distressed fetus causes interstitial pneumonia in neonatal foals, calves, and human infants. The diagnosis is based on histologic findings.

Question:

What are three causes of diffuse interstitial lung disease in neonatal foals? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage

EIPH commonly manifests as bilateral epistaxis immediately after racing. Infrequently, hemorrhage is so massive that it causes sudden death during a race, and this condition is known as exercise-associated fatal pulmonary hemorrhage (EAFPH).

Dictyocaulus arnfieldi

Donkeys are the natural host, and this nematode may cause disease in horses exposed to pastures contaminated by donkey feces. Donkeys are not numerous in Ontario, but D. arnfieldi is rarer still. As for other Dictyocaulus spp., the worms are grossly visible in the caudal bronchi.

Question:

Indicate the distribution and likely cause of bronchopneumonia in a neonatal foal. (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

Indicate the distribution and likely cause of interstitial lung disease in a neonatal foal. (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

What is the pathophysiologic basis for dyspnea in a foal with interstitial lung disease? That is, what are two alterations in lung physiology that cause respiratory failure? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Answer:

Bastard strangles vs. purpura hemorrhagica: which of these is a consequence of bacteremia, and which is an immune complex-mediated disease?

Bacteremia —> bastard strangles (visceral abscesses)

Circulating immune complexes —> purpura hemorrhagica (vasculitis, petechiae, and edema)

Answer:

What is the gross appearance of guttural pouch mycosis?

A focal plaque of fungal growth, often with necrosis and inflammation of the adjacent tissue, and sometimes, with hemorrhage filling the pouch.

Answer:

List 2 clinically serious sequelae to mycosis of the guttural pouch in horses.

Hemorrhage from carotid artery, facial nerve paralysis, and others.

Answer:

What anatomic structure is targeted by the lesions of heaves (severe equine asthma)?

Bronchioles: small airways.

Answer:

What are 3 mechanisms of airway obstruction in heaves?

Bronchoconstriction. Mucus and neutrophils in the lumen. Edematous swelling of the airway mucosa.

Answer:

Describe the expected gross lesions of Rhodococcus equi infection of the respiratory tract.

Cranioventral bronchopneumonia, with abscessation or granulomas within the consolidated cranioventral areas of lung.

Answer:

Why is Rhodococcus pneumonia resistant to many antibiotics that are effective for other forms of pneumonia in horses?

Intracellular location within macrophages. Presence within abscesses. (Drug delivery is poor to both of these locations).

Answer:

In Rhodococcus infection, what are the two pathogeneses of the lesions in the colonic lymph nodes?

Ingestion of Rhodococcus equi from the environment (dust, soil)

Bacteria are coughed up from lung lesions, swallowed, and reach the intestine.

Answer:

How does the pathogenesis of fibrinous pleuritis in a feedlot calf differ from that in a racehorse?

Feedlot calf: hematogenous spread of Histophilus somni results in pleuritis with normal lung tissue.

Racehorse: the pleuritis is usually secondary to an underlying bacterial pneumonia.

Answer:

In 2–8-month-old foals with interstitial (bronchointerstitial) pneumonia, what is the gross appearance of the lung?

Diffusely firm, rubbery texture, fails to collapse.

Answer:

In 2–8-month-old foals with interstitial (bronchointerstitial) pneumonia, what is the common concurrent disease?

Rhodococcus equi pneumonia, which may be either mild or severe.

Answer:

What are three causes of diffuse interstitial lung disease in neonatal foals?

Hyaline membrane disease, septicemia, Equine herpesvirus-1, meconium aspiration syndrome.

Answer:

Indicate the distribution and likely cause of bronchopneumonia in a neonatal foal.

Cranioventral distribution.

Streptococcus zooepidemicus & others.

Answer:

Indicate the distribution and likely cause of interstitial lung disease in a neonatal foal.

Generalized/diffuse distribution.

Hyaline membrane disease, septicemia, EHV-1 infection, meconium aspiration.

Answer:

What is the pathophysiologic basis for dyspnea in a foal with interstitial lung disease? That is, what are two alterations in lung physiology that cause respiratory failure?

Obstruction to gas exchange, reduced lung compliance, reduced functional lung volume.