7 Respiratory Diseases of Dogs

| Course priority #1 | Course priority #2 | Course priority #3 | |

| Dogs |

|

|

|

Nasal diseases

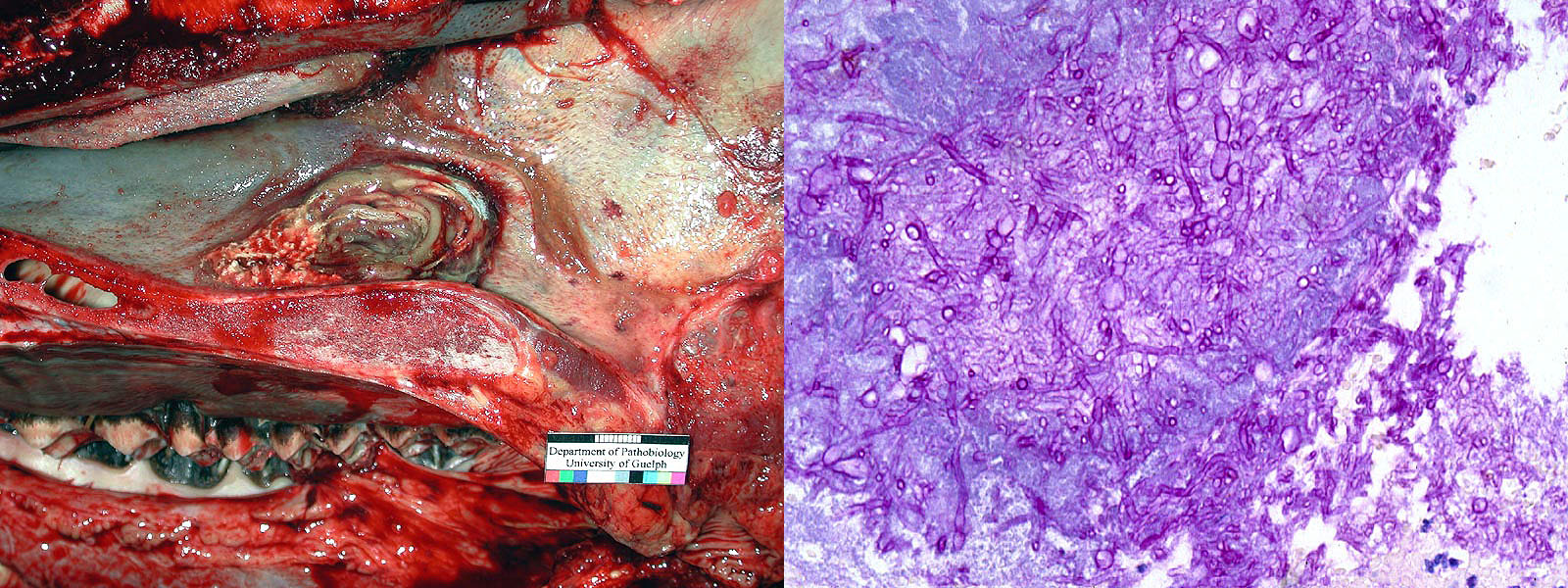

Nasal aspergillosis causes focal plaques in the nasal cavity, each formed by mats of fungal hyphae, much like plaques of mold growing on bread. Clinical signs are typically unilateral and include sneezing, nasal discharge, epistaxis, and/or nasal depigmentation.

The pathogenesis is obscure, but inhalation of large numbers of fungal hyphae might play a role. Immunosuppression seems not to be a predisposing cause.

The diagnosis is made by identifying plaques of fungal hyphae in biopsies obtained by rhinoscopy, or cytologic or histologic examination of nasal flushes. As for nasal cancer, the histologic diagnosis is usually easy of the fungal plaques are harvested by the clinician, but there is no hope of making a histologic diagnosis if the plaque is not sampled.

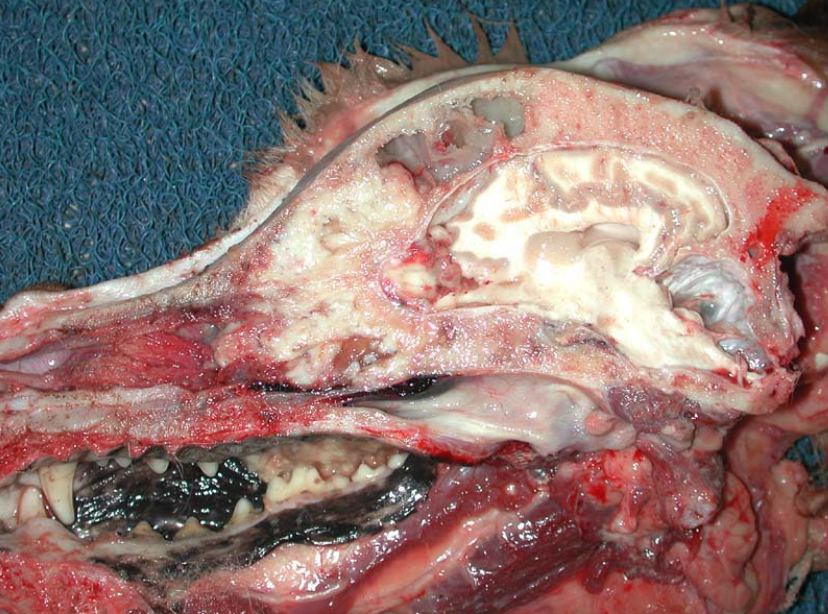

Nasal neoplasia. Adenocarcinoma is the most common nasal tumour of dogs, while chondrosarcoma and other tumours are less frequent. Nasal tumours cause nasal discharge, sneezing, hemorrhage, and sometimes nasofacial deformity or stertor.

Nasal adenocarcinoma does metastasize, but late in the disease course. Locally invasive and destructive growth is the more common clinical problem and the eventual reason for death or euthanasia. This tumour may cause exophthalmos by invasion of the retro-orbital space, seizures by invading the cribriform plate into the brain, invasion into oral cavity, or formation of a subcutaneous mass. The diagnosis is based on histologic or cytologic examination of masses that are identified in the nasal cavity. MRI or aggressive rhinoscopy may be required to identify the tumour, but this is critical to make the diagnosis.

Foreign body rhinitis: the inflammatory response is non-specific, and diagnosis depends on clinical identification of foreign material.

Allergic rhinitis: histologic lesions of eosinophilic rhinitis are suggestive but not specific, and the diagnosis must be made in conjunction with clinical signs, seasonality, and response to therapy.

Lymphoplasmacytic rhinitis: This type of inflammatory reaction can result from many chronic stimuli, but some cases respond to anti-inflammatory therapy and are thought to be immune-mediated.

Uncommon nasal diseases: Pneumonyssoides caninum (nasal mite of dogs), Rhinosporidium seeberi (protozoan).

On the use of nasal biopsies. Nasal biopsies are highly useful in establishing the diagnosis of nasal neoplasms and nasal aspergillosis. In other cases, the lesions may be suggestive but non-diagnostic of other conditions. The two major limitations are: (1) many nasal diseases cause non-specific neutrophilic or lympho-plasmacytic inflammatory lesions, and (2) histologic diagnosis is most specific for diseases that cause focal lesions, but it may be a clinical challenge to identify and sample these focal lesions. Nonetheless, biopsy is needed to make a specific diagnosis, for a subset of nasal diseases of dogs.

Question:

List two nasal diseases of dogs for which biopsy provides a definitive diagnosis. (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

Is immunosuppression a risk factor for nasal aspergillosis? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Diseases of the larynx, trachea, and bronchi

Laryngeal paralysis. A common clinical condition especially of older dogs, but not usually a cause of death unless there is secondary aspiration pneumonia.

Brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome. Brachycephalic dogs, particularly bulldogs, may have a spectrum of malformations that cause airway obstruction: stenotic nares, everted laryngeal ventricles, elongated soft palate, and tracheal hypoplasia. Affected dogs may develop acute exacerbations due to aspiration pneumonia, probably because of the stertorous inspiratory effort.

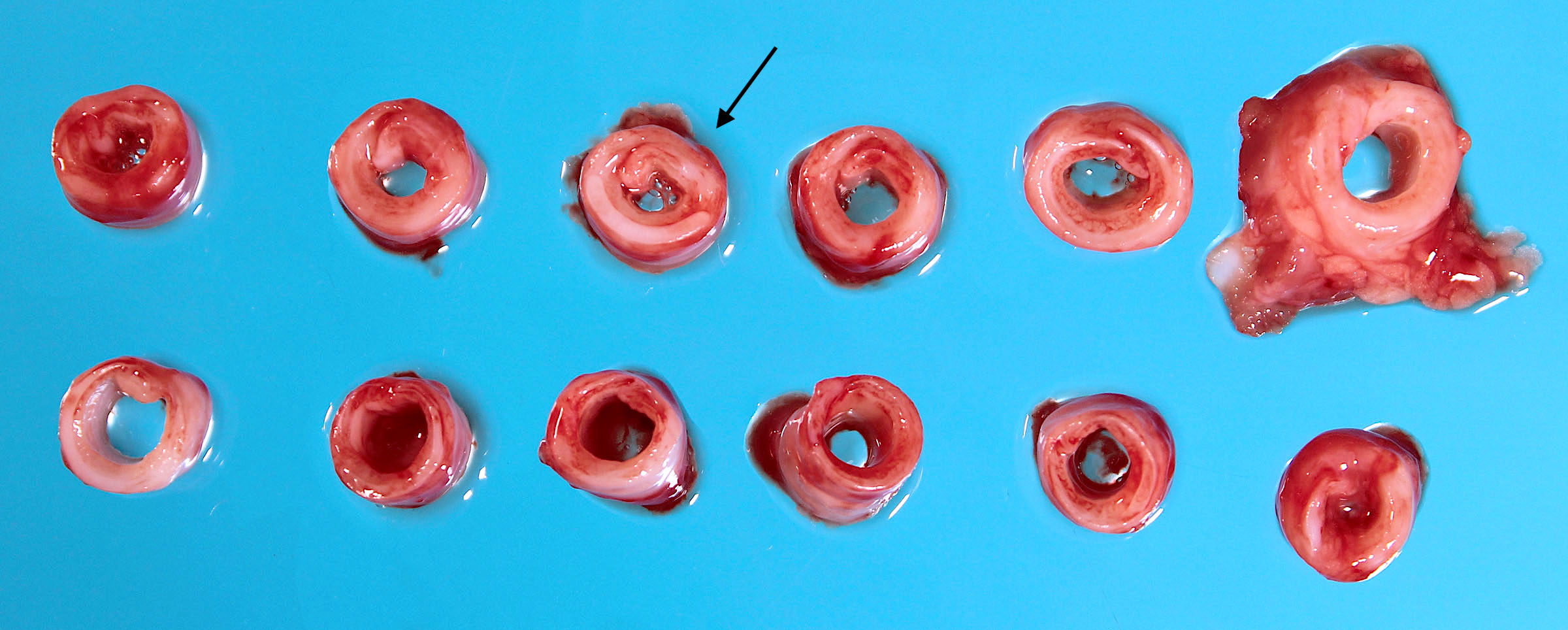

Tracheal collapse causes a chronic, honking, non-productive cough in small-breed adult dogs. Some affected dogs also have chronic bronchitis and/or myxomatous mitral valve disease. The gross lesions are a lack of normal rigidity of the tracheal cartilage, with flattening of tracheal rings, and a widened dorsal tracheal membrane. The cause is not known.

Infectious bronchitis/kennel cough is mainly caused by Bordetella bronchiseptica, with viruses such as canine adenovirus-2 and canine parainfluenza virus playing a role in some cases. Clinical signs are an acute onset of non-productive or productive cough usually after kennelling or other exposure to dogs. Mortality is rare.

Chronic bronchitis occurs in older, obese, small-breed dogs. There is a lack of specific lesions: chronic inflammation, and hyperplasia of mucus-secreting goblet cells.

Bacterial bronchopneumonia

Some cases of bronchopneumonia in dogs result from infection with relatively virulent bacterial pathogens: Bordetella bronchiseptica, Streptococcus sp., Staphylococcus sp., extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli, and others. These can cause outbreaks in kennel or shelter situations. Sporadic cases can be caused by the same pathogens or by other opportunistic bacterial pathogens. Predisposing causes should be considered such as viral infection, malnutrition or debilitation, chilling, crowding that increases the opportunity for pathogen transmission, neutropenia (parvoviral infection, chemotherapy), and rarely immunodeficiency such as ciliary dyskinesia.

Compared to such opportunistic infections, aspiration pneumonia is more frequent in dogs. Aspiration results from vomiting (parvoviral enteritis, inflammatory bowel disease), regurgitation (megaesophagus, myasthenia gravis), reduced swallowing reflex (general anesthesia, laryngeal disease, neurologic disease), brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome, or cleft palate.

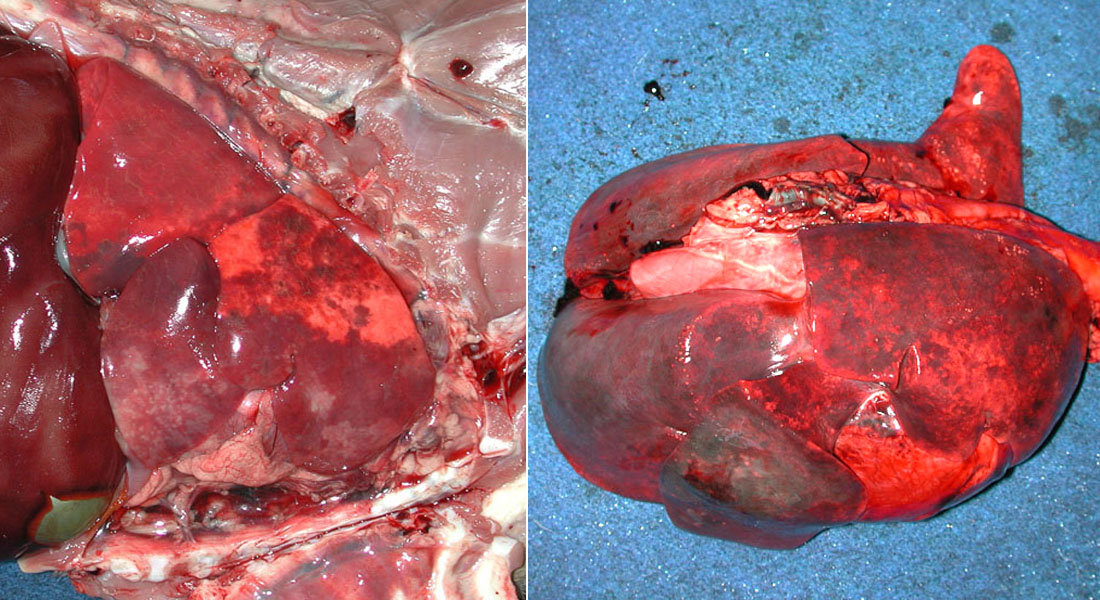

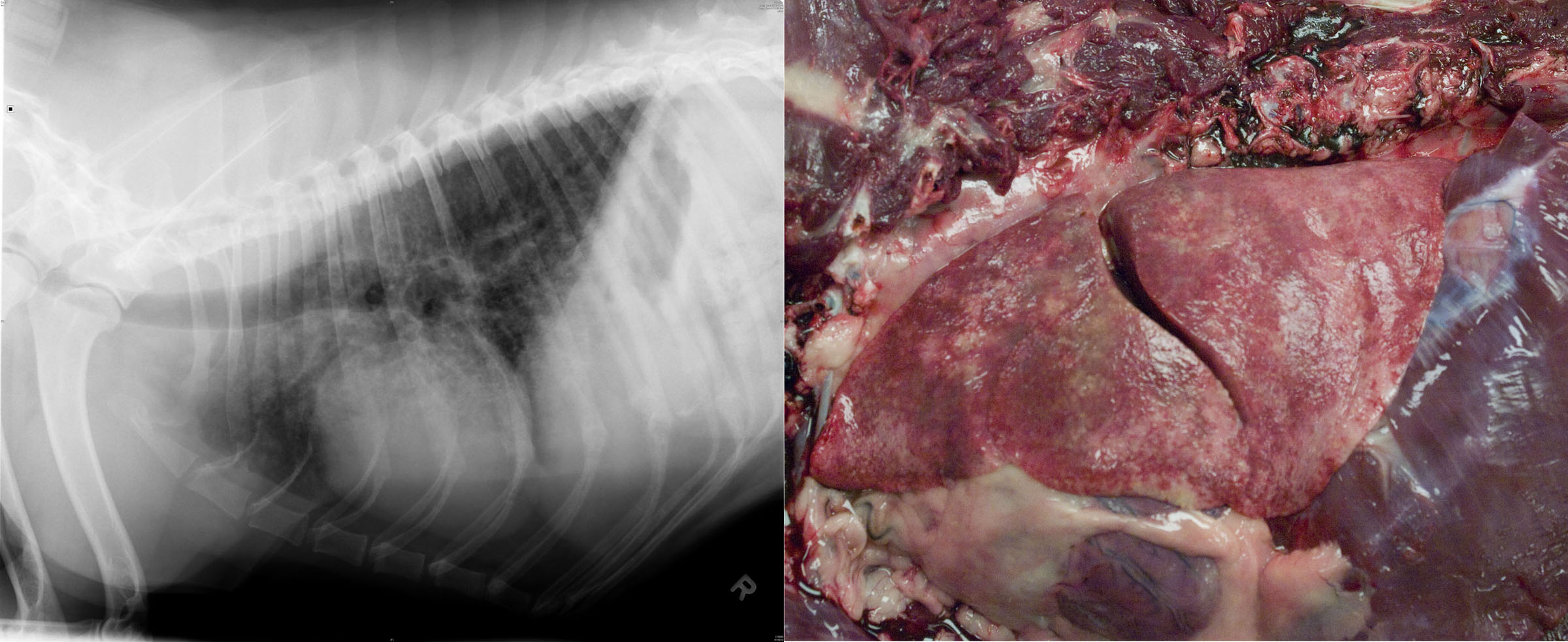

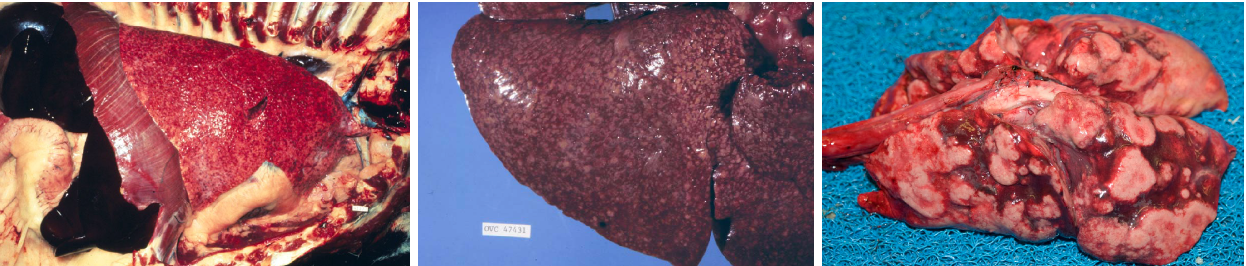

Morphology. The gross lesions may cause cranioventral reddening and consolidation, as is typical of bronchopneumonia, but lesions of bronchopneumonia in dogs may sometimes be more widespread throughout the lung. Acute bronchopneumonia in dogs is often more hemorrhagic than in other species, and the pneumonia can easily be mistaken for pulmonary hemorrhage. Lesions of aspiration pneumonia are typically focal, unilateral, or at least asymmetrical. Aspiration pneumonia in monogastric animals is often less necrotizing and foul-smelling than in ruminants.

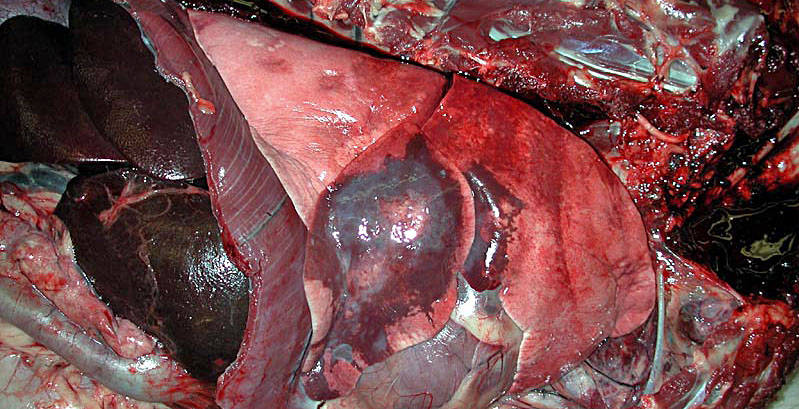

In dogs, even if the entire lung is dark red, consolidation may affect only a single lobe, and this lobar pneumonia most frequently involves the right middle lobe. Aspiration pneumonia should be considered in such cases. The differential diagnosis for lobar lesions in dogs includes lung lobe torsion, and histiocytic sarcoma which is uncommon but often invades to fill a single lobe of the lung.

Question:

List three predisposing factors for aspiration pneumonia in adult dogs, and two for puppies less than 5 months old. (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

List two bacterial pathogens that can cause outbreaks of lung disease. What form of lung disease is expected? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

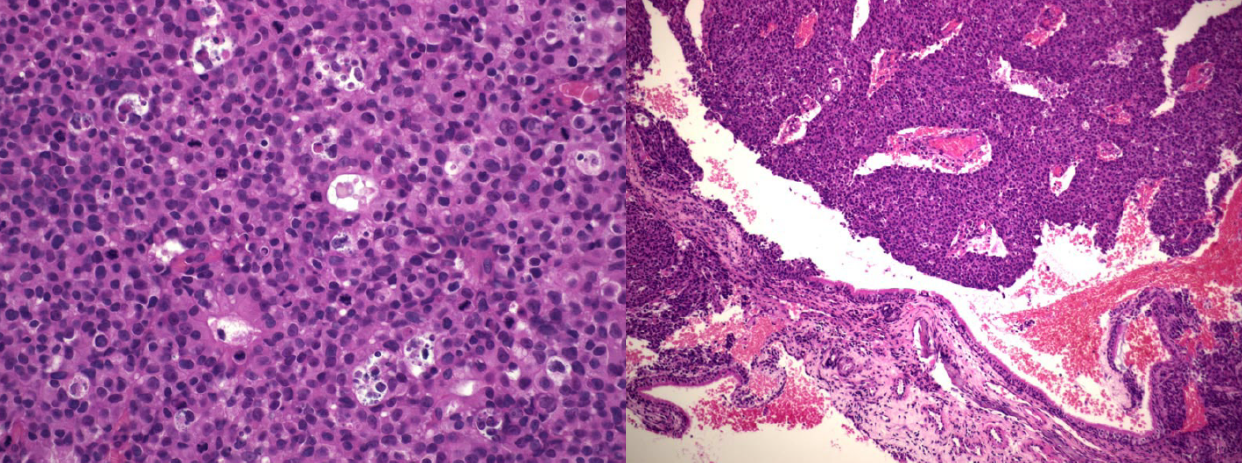

Canine distemper

This is caused by canine distemper virus, a morbillivirus (Paramyxoviridae) related to measles. The host range includes canids, mustelids (e.g. ferrets, which are very sensitive), procyonids (e.g. raccoons), and seals. Although the virus is endemic in Ontario wildlife, clinical disease is uncommon in dogs in Ontario, a great success of vaccination. The disease is very common where vaccination is not widely practiced, and cases do occur in unvaccinated animals, pet stores and shelters in Ontario.

Acquired by inhalation, the infection causes viremia and systemic infection of epithelial and lymphoid tissues. Immunosuppression, due to destruction of lymphoid tissue, predisposes to bacterial pneumonia, toxoplasmosis, and other infections.

Clinical signs reflect one or more of respiratory disease, encephalitis, and/or immunosuppression. Acute signs include fever, oculonasal discharge, cough, dyspnea, and depression. Neurologic signs may include ataxia, convulsions, myoclonus, blindness. Skin lesions of nasal and foot pad hyperkeratosis occur in chronic stages.

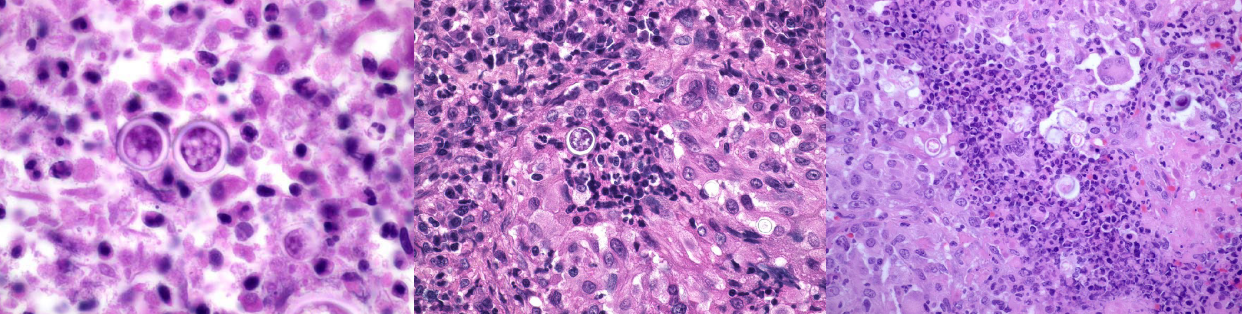

Morphology: Gross lung lesions typically affect the cranioventral lung, with patchy areas of reddening and slight firmness. The gross findings are not specific. Histologic lesions in lung and other tissues are characteristic, with epithelial necrosis in which surviving cells form intracytoplasmic (and sometimes intranuclear) inclusion bodies and syncytial cells.

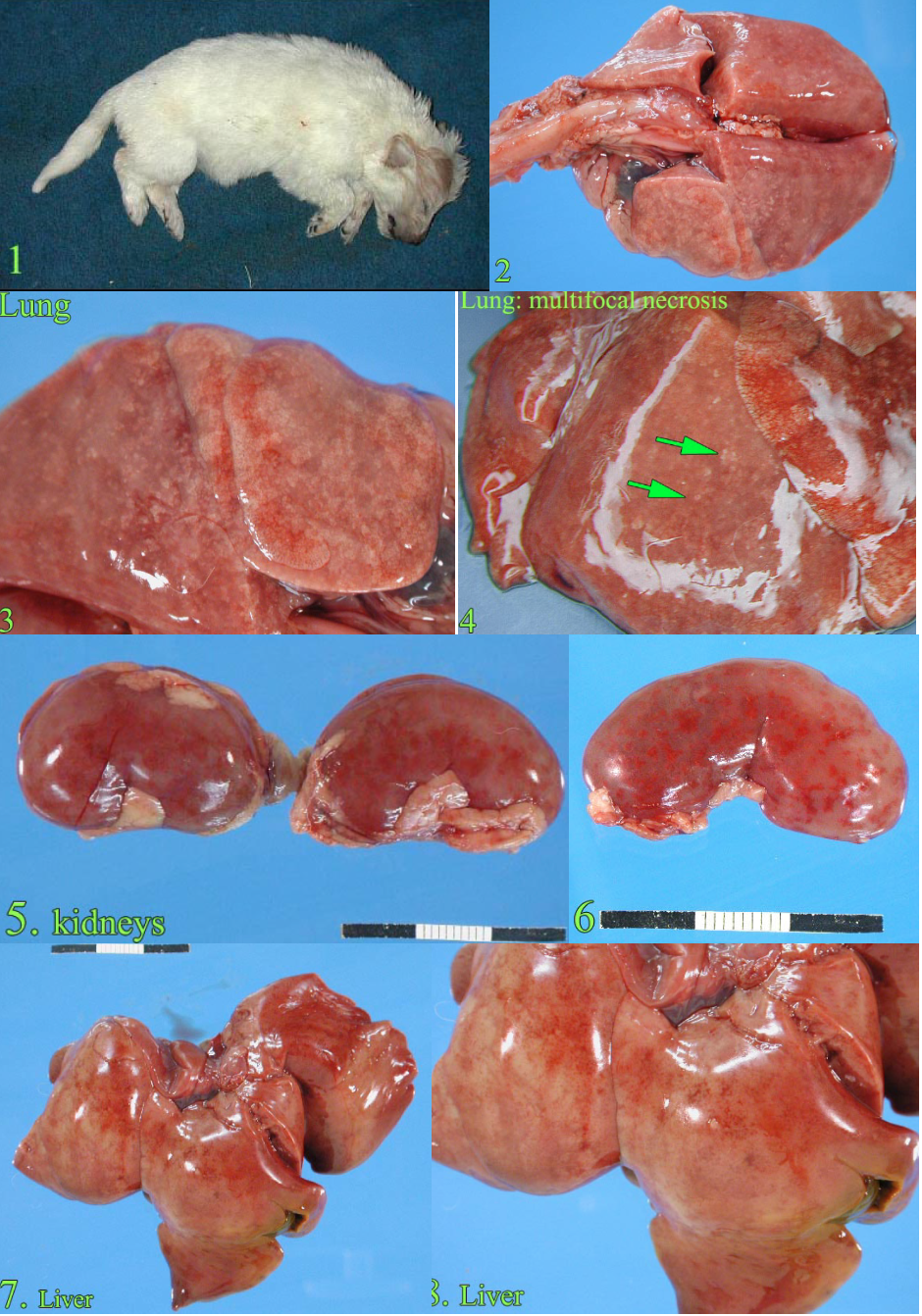

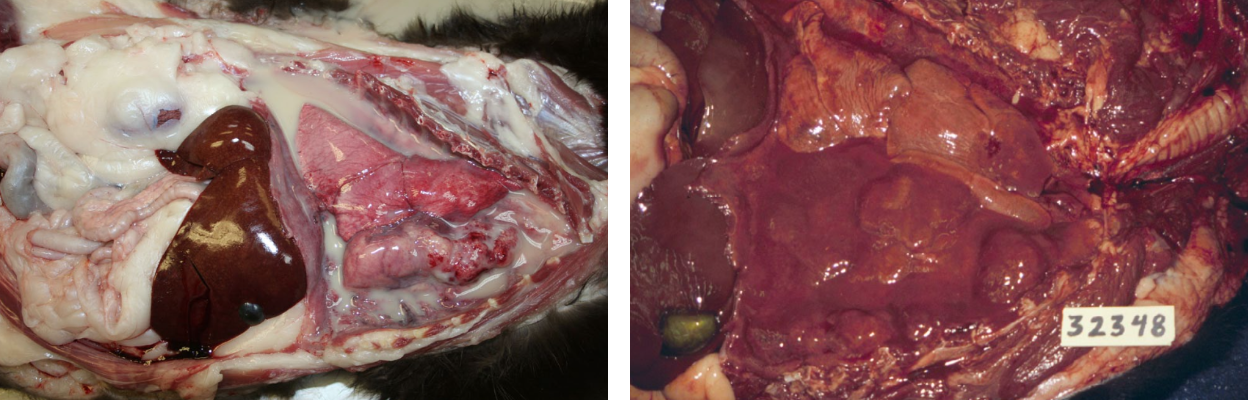

Canine herpesvirus

Canine herpesvirus causes fatal viremia in puppies less than about 6 weeks of age. The infection may be transmitted by new dogs entering the population, or latent infections in the bitch may be re-activated at the time of parturition, thus resulting in infection and disease in the neonates. The virus grows better at temperatures cooler than 37˚C, and chilling of neonatal puppies is thus a risk factor. Lesions are of diffuse interstitial pneumonia and multifocal necrosis in kidney and liver. These foci of necrosis often have hemorrhage, appearing as red or white spots in kidney, liver, and lung.

The histologic lesions are characteristic, as intranuclear inclusion bodies are frequent.

Non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema and Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Left heart failure causes pulmonary congestion and edema. A much less common similar condition has causes other than heart failure, and is thus known as non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema (NCPE) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). ARDS is a term that defines an acute onset of severe hypoxemia, without left atrial hypertension. In humans, ARDS is frequent, often fatal, and usually secondary to other diseases. A similar condition is recognized in dogs. Some cases have acute bacterial pneumonia. Others represent diffuse interstitial lung disease, and are the result of a broad spectrum of initiating conditions that result in damage to alveolar epithelium or endothelium:

- Systemic diseases that increase the permeability of lung capillaries: massive trauma, sepsis, SIRS such as from pancreatitis or immune hemolytic anemia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, lung trauma/contusion, whole-body or head trauma, strangulation

- Conditions that damage alveolar epithelium: aspiration of sterile gastric acid, viral infection, toxicants, inhalation of toxic fire gases (smoke inhalation)

Morphology: The gross appearance is of interstitial lung disease: heavy, wet, diffusely firm lungs. Histologic lesions are of alveolar edema with hyaline membranes and, in later stages, proliferation of type II pneumocytes.

Question:

What gross lesions in the lung are expected with heart failure? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

What 2 histologic lesions are characteristic of acute interstitial lung disease (ARDS) in dogs? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Eosinophilic lung disease

(aka Eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy, eosinophilic granulomatosis)

Eosinophilic lung diseases in dogs are rare. They include a confusing spectrum of names, reflecting the fact that these probably include several distinct diseases. Recognize that eosinophilic lung diseases of dogs form infiltrates in the lung that are visible grossly and radiographically, some diseases are immune-mediated while others are caused by parasitism such as Dirofilaria. Many cases are responsive to corticosteroid therapy, and are therefore more commonly seen clinically than at postmortem.

Question:

Briefly explain how a thymoma in an adult dog leads to bronchopneumonia. (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Uremic pneumonopathy

Uremic toxins injure blood vessels in the lung, appearing as diffusely reddened lungs with histologic evidence of mineralization of alveolar septa. Some affected dogs have clinical signs of hyperpnea or dyspnea.

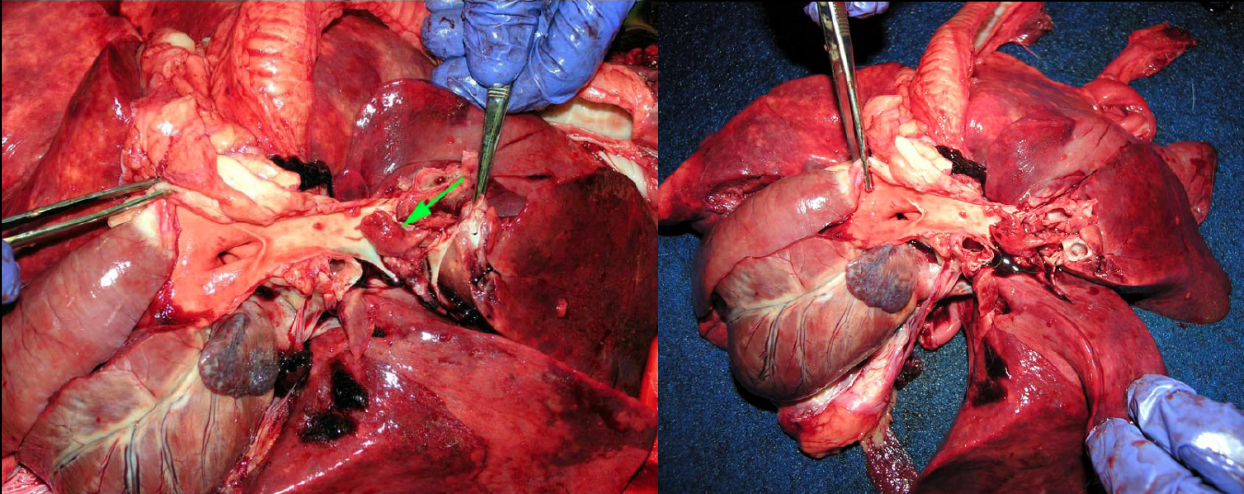

Pulmonary thromboembolism

Grossly visible thrombi within pulmonary arteries are a surprise when performing a postmortem examination on a dog with acute respiratory distress and otherwise non-diagnostic lesions in the lung or heart. But, you need to open the pulmonary artery to detect this lesion! This is best done when dissecting the right heart: continuing the cut along the right ventricular outflow tract, pulmonic valve, and the right and left branches of the pulmonary artery deep into the caudal lobes of the right and left lungs.

This condition is always secondary to another disease:

- Embolism from other sites such as endocarditis, or jugular phlebitis secondary to venipuncture or catheterization

- Increased coagulative tendency: glomerular disease (with loss of anti-thrombin), immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, disseminated neoplasia, hyperadrenocorticism, corticosteroid therapy, or heartworm disease.

Question:

What is the most inexpensive method of identifying pulmonary emboli at necropsy? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Blastomycosis

Blastomyces dermatitidis is a dimorphic fungus: it grows as a yeast form at 37˚C, but as hyphae at environmental temperatures. The hyphae are found in the soil and are infectious to animals and humans. The yeast form is not contagious, so handling infected tissues should not cause respiratory infection … but you can develop a skin infection if you cut yourself with a contaminated scalpel.

Blastomycosis is particularly common in certain geographic areas and related to soil chemistry, including one area focused on Kenora, extending from Winnipeg to Sudbury and the Ottawa Valley.

Infection begins in the lung, and may spread to skin, eye, bone, and/or other viscera. Infection induces granulomatous inflammation, forming multiple soft white nodules. In older dogs, metastatic neoplasia is a more likely differential diagnosis.

Although the multifocal appearance of the pulmonary lesions suggests an embolic pneumonia, the pulmonary infection is acquired by inhalation. It seems likely that the multiple nodules could represent intrapulmonary spread from a primary focus, but this has not been studied.

The diagnosis depends on identifying yeast in affected lesions by cytologic examination of aspirates or impression smears, or in histologic sections of affected tissues. Clinically, detection of Blastomyces antigen in urine is an effective and non-invasive test.

Question:

Other than lung, what 3 tissues are most often affected by blastomycosis? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Other fungal pneumonias

Dogs occasionally develop pneumonia due to Cryptococcus neoformans or Cryptococcus gattii (more common in cats), Histoplasma capsulatum (enteric disease is more common), and Coccidioides immitis (in the arid southwestern United States).

Parasites

Dirofilaria immitis resides in the pulmonary arteries. It is covered elsewhere.

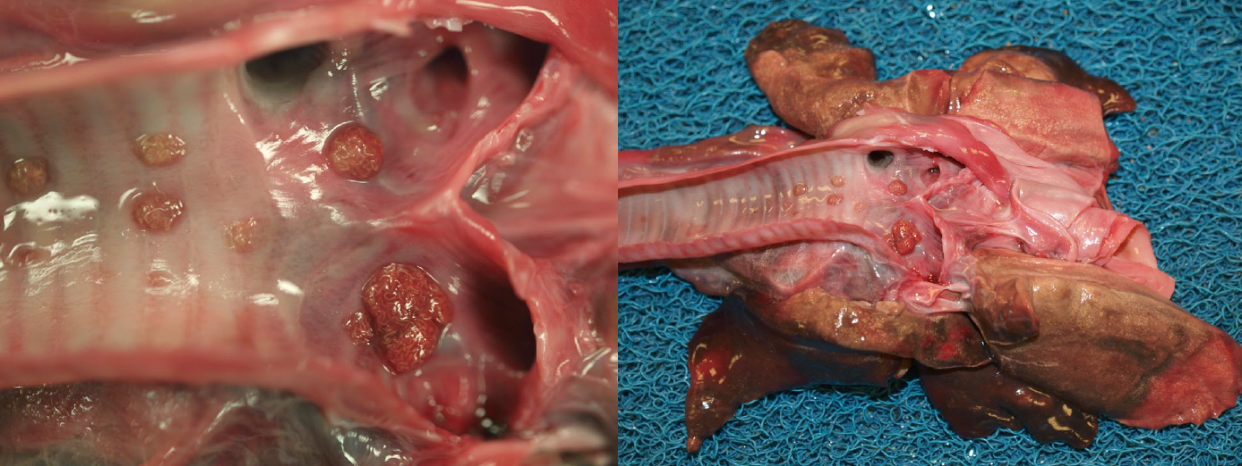

Oslerus osleri (formerly Filaroides osleri) forms nodules at the tracheal bifurcation, and is usually an incidental finding.

Crenosoma vulpis is a thread-like worm in bronchi. Snails or slugs are intermediate hosts. The disease is seen in the Maritimes.

Paragonimus kellicotti: see cat parasites.

Toxocara canis larval migration occasionally causes mild coughing in puppies, or rarely more severe disease.

Angiostrongylus vasorum. A nematode parasite of the lung tissue and pulmonary vessels, that is quite common on the eastern and western shores of the Atlantic Ocean, but rarely identified in Ontario.

Pulmonary neoplasia

Primary lung tumours are infrequent in dogs. Adenocarcinoma is the most common, followed by squamous cell carcinoma, histiocytic sarcoma, and various sarcomas including chondrosarcoma.

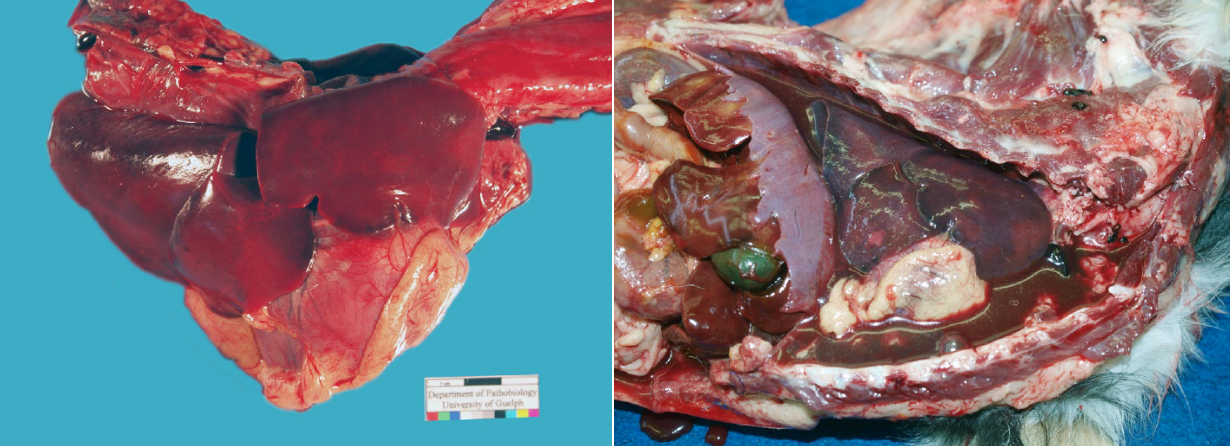

Most lung tumours are metastases that have originated elsewhere. Common canine cancers that metastasize to the lung include carcinomas (mammary, thyroid, urothelial), oral melanoma, splenic or right atrial hemangiosarcoma, osteosarcoma of long bones, histiocytic sarcoma, and lymphoma. Clinical manifestations of lung cancer were discussed in the section on general pathology.

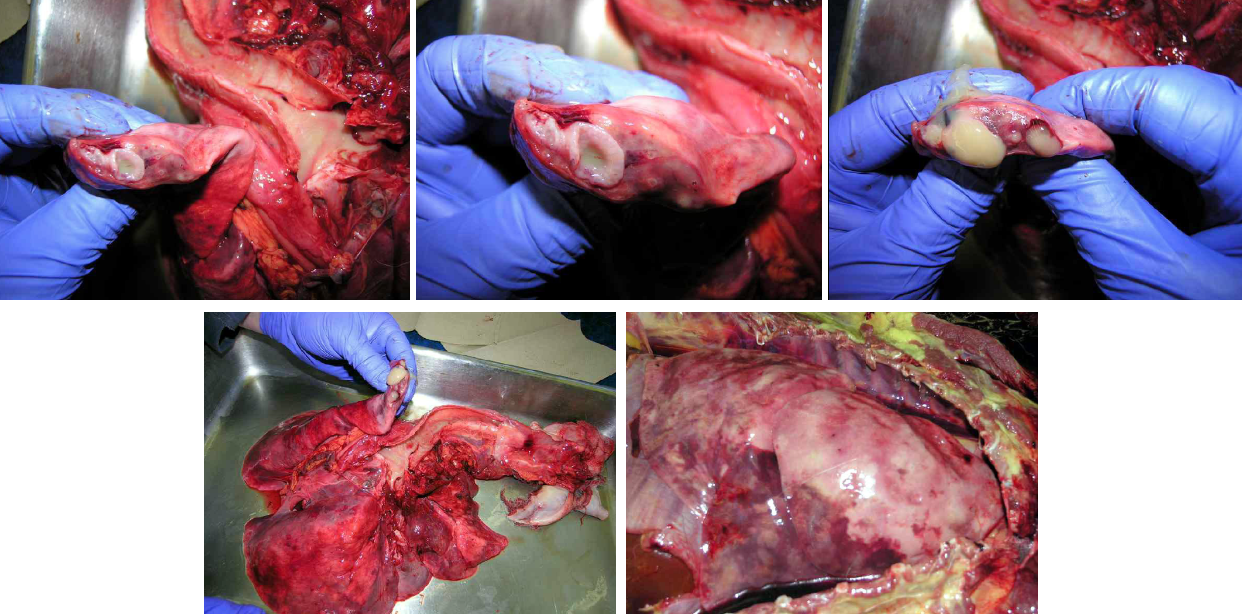

Pleuritis

Chronic and progressively worsening pleuritis occurs in large-breed dogs secondary to penetrating injury or migrating plant awns contaminated with Actinomyces spp. or Nocardia asteroides. The chest cavity is filled with exudate—often bloody—and there is atelectasis as a result.

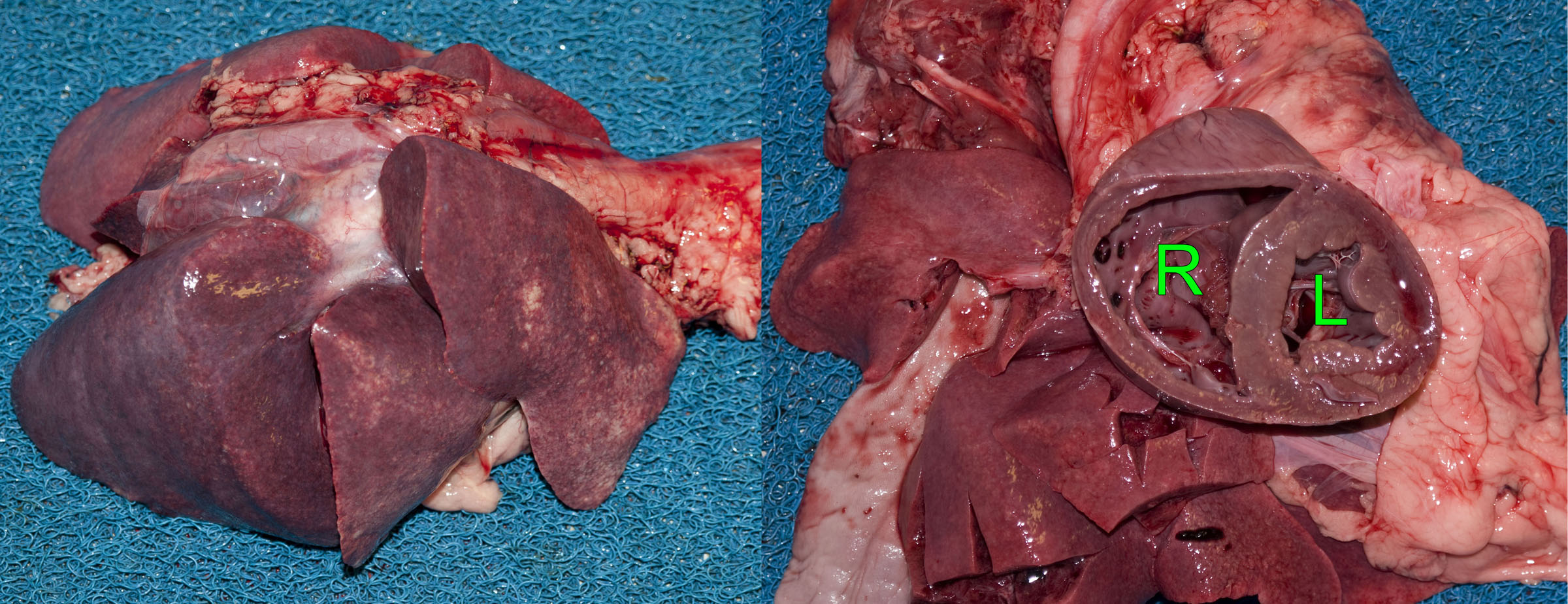

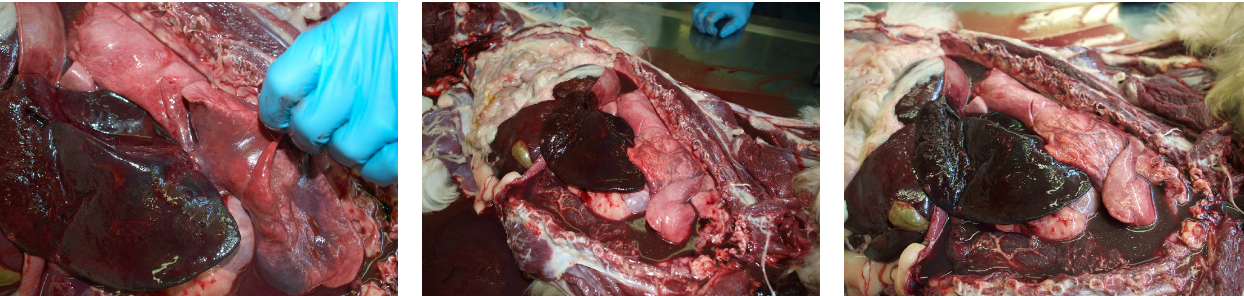

Lung lobe torsion

Dogs present with an acute onset of respiratory distress. Look for an underlying tumour. Because this often affects the right middle lung lobe, it can resemble aspiration pneumonia. There is usually concurrent hydrothorax, chylothorax or sometimes hemothorax. It is uncertain if the pleural effusion precedes and predisposes to torsion, or if venous obstruction by the torsion causes the effusion; both can probably occur.

Question:

What are the two main differential diagnoses for swelling and red discolouration of the right middle lung lobe? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Answer:

List two nasal diseases of dogs for which biopsy provides a definitive diagnosis.

Nasal neoplasia, aspergillosis.

Answer:

Is immunosuppression a risk factor for nasal aspergillosis?

No, immunosuppression predisposes to systemic aspergillosis, but not nasal aspergillosis.

Answer:

List three predisposing factors for aspiration pneumonia in adult dogs, and two for puppies less than 5 months old.

Adults: anesthesia, neurologic disease, laryngeal disease, megaesophagus, myasthenia gravis, …

Puppies: cleft palate, parvoviral enteritis.

Answer:

List two bacterial pathogens that can cause outbreaks of lung disease. What form of lung disease is expected?

Bordetella bronchiseptica, Streptococcus canis.

Bronchopneumonia.

Answer:

What gross lesions in the lung are expected with heart failure?

Diffuse pulmonary edema and congestion: red, heavy lungs that ooze fluid from the cut surface and have excessive foam in the trachea.

Answer:

What 2 histologic lesions are characteristic of acute interstitial lung disease (ARDS) in dogs?

Hyaline membranes, alveolar edema.

Answer:

Briefly explain how a thymoma in an adult dog leads to bronchopneumonia.

Thymoma —> megaesophagus —> regurgitation —> aspiration pneumonia

Answer:

What is the most inexpensive method of identifying pulmonary emboli at postmortem examination?

Open the pulmonary arteries all the way to the caudal lobes of the lung!

Answer:

Other than lung, what 3 tissues are most often affected by blastomycosis?

Skin, eye, bone.

Answer:

What are the two main differential diagnoses for swelling and red discolouration of the right middle lung lobe?

Aspiration pneumonia, lung lobe torsion.