4 Pleural diseases

Pleural diseases are relatively common in small animal practice. Fluid within the pleural cavity compresses the lungs, leading to atelectasis, and failure of ventilation of the lung.

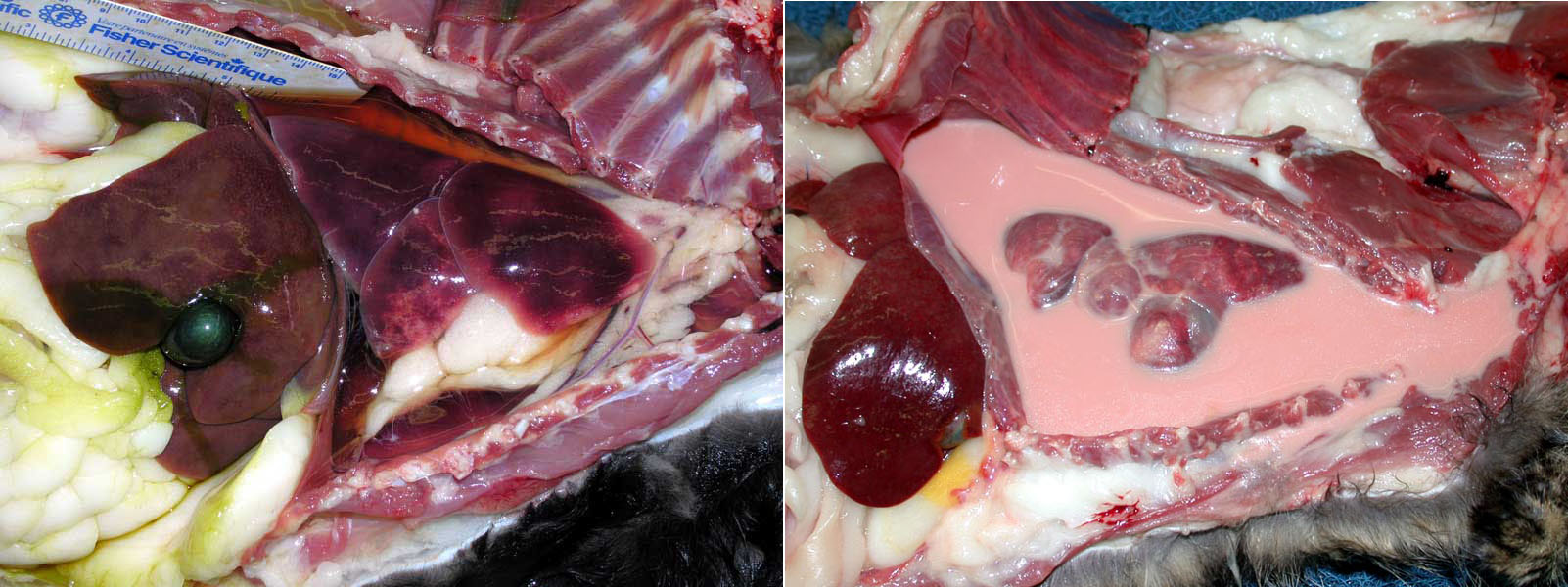

Hydrothorax

Think of this as “edema of the pleural space”. Clear fluid (transudate) fills the pleural cavity and compresses the lungs. The major mechanisms of fluid transudation (and their common causes) are:

- Increased venous pressure (right heart failure in all species, plus left heart failure in cats; excessive intravenous fluids; lung lobe torsion)

- Reduced oncotic pressure: (hypoproteinemia)

- Lymphatic obstruction (eg by a tumor, abscess, granuloma)

- Increased vascular permeability: but, this causes an exudate rather than transudate; thus, the fluid is usually cloudy rather than clear & watery

- Finally, if there is ascites, some of the peritoneal fluid can leak into the pleural cavity through tiny pores in the diaphragm

Chylothorax

Milky opaque pleural fluid, rich in triglyceride and lymphocytes, arising from loss of lymph fluid into the pleural space.

The major causes are:

- Heart failure. Increased central venous pressure prevents drainage of lymph from the thoracic duct into the vena cava.

- Lung lobe torsion.

- Many cases are idiopathic.

- Uncommonly due to obstruction of the thoracic duct by tumours, or other masses, or rarely due to traumatic rupture of thoracic duct.

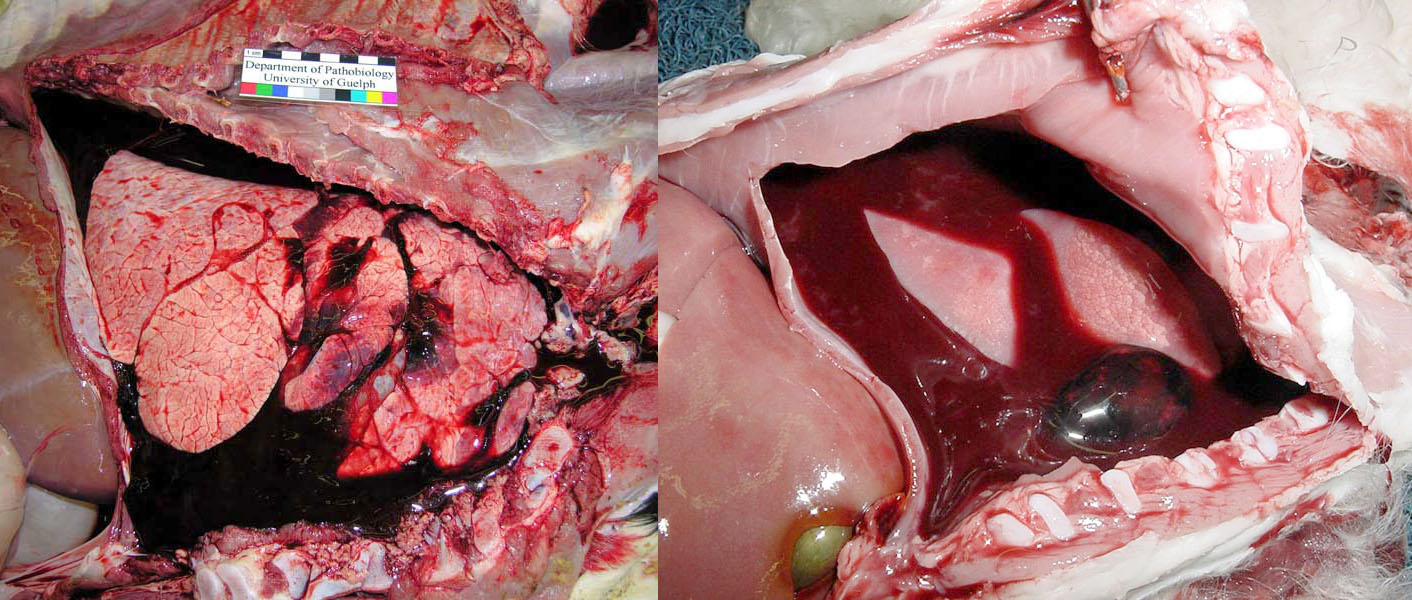

HEMOTHORAX

Causes include trauma (e.g. fractured ribs), ruptured tumours (especially hemangiosarcoma), idiopathic hemothorax in dogs, anticoagulant rodenticide toxicity, and thymic hemorrhage syndrome in young dogs.

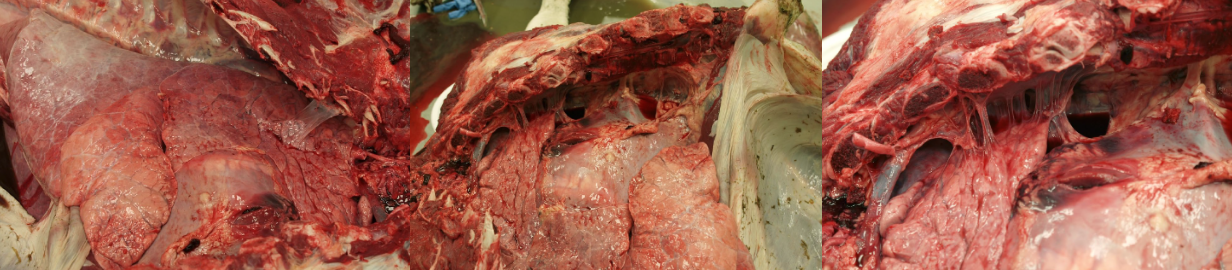

PLEURITIS

Inflammation of the pleural cavity usually represents bacterial infection, and the bacteria can arrive in the pleural space by three routes:

- External penetrating injury: cat bite wounds, penetrating injury, plant awn migration in dogs, etc. Cellulitis of the neck such as from penetrating injury to the pharynx from foreign bodies can spread by gravity into the pleural cavity.

- Extension from bacterial pneumonia or rupture of a lung abscess. This is the common cause of pleuritis in adult horses. Careful inspection reveals consolidation of the underlying lung tissue.

- Hematogenous spread: bacteremia, such as in neonates with omphalitis or failure of passive transfer, or feedlot cattle with pleuritis caused by Histophilus somni. Feline infectious peritonitis usually induces peritoneal lesions, but some cats present with pleural effusion.

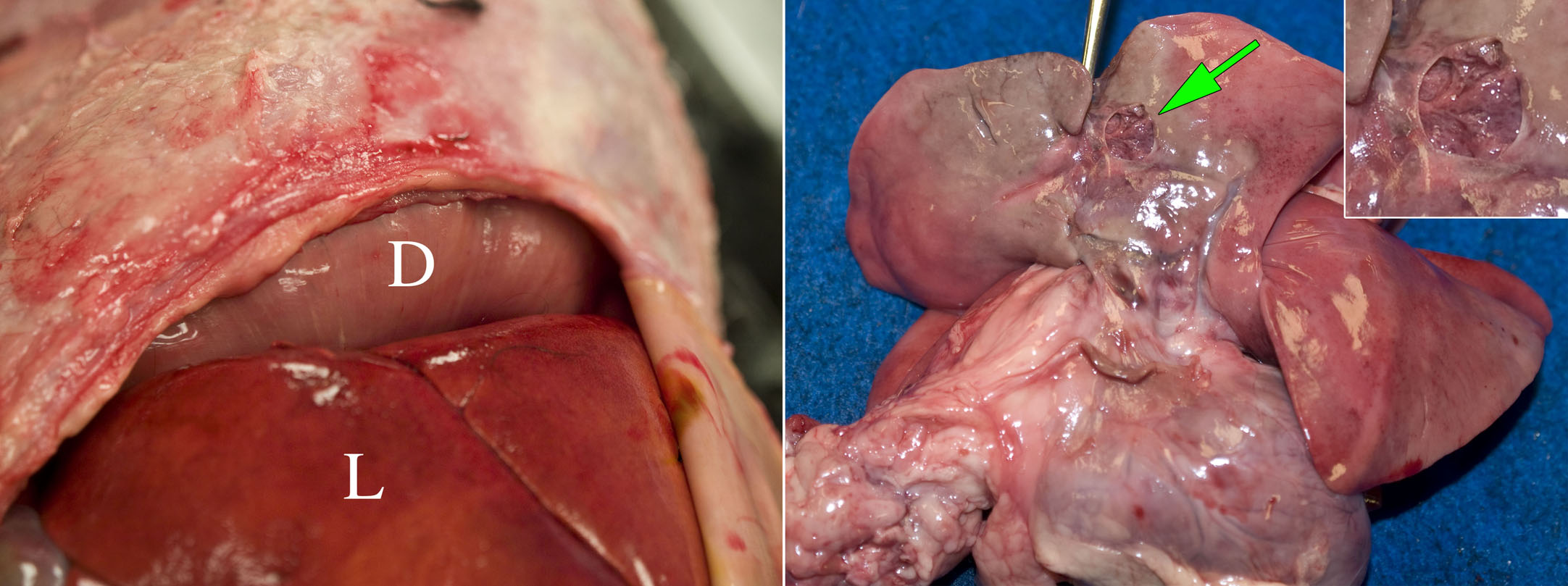

Pneumothorax

Pneumothorax refers to the presence of air in the pleural space. Diagnostic features at postmortem examination:

- The in-rush of air that is normally heard when the diaphragm is opened will not be detected, but this can be difficult to detect in small animals.

- Incise the diaphragm when the abdomen is opened but the chest is still intact. Normally, as viewed from the abdomen, the concavity of the diaphragm collapses as air enters the chest, but this concavity is absent in cases of pneumothorax.

- Atelectasis of the lungs, with no apparent cause (such as pleural fluid, etc.).

External pneumothorax: penetrating injury that allows air into the pleural space.Internal pneumothorax: rupture of a pulmonary bulla, or penetrating injury that punctures the lung. The pleural lesion can be impossible to see. To detect the site of leakage, tie off the trachea with string, immerse the lungs in water, and use a large syringe to inject air into the trachea. As the lungs inflate with air, bubbles will leak from the site of the ruptured bulla. A “low-tech” diagnostic test; molecular analysis is not needed!

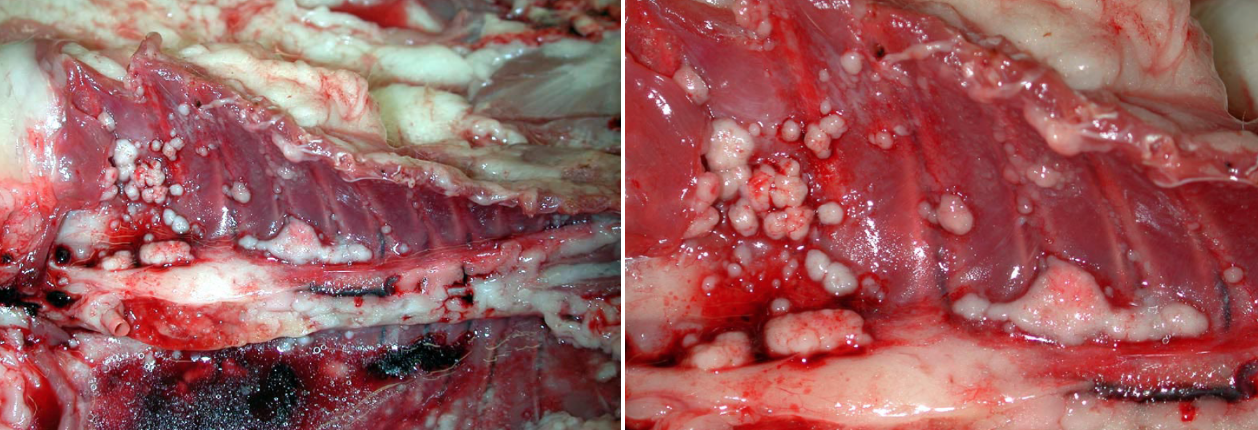

Pleural neoplasms

Lung tumours, such as pulmonary adenocarcinoma, may invade the pleura and spread widely in the pleural space. The metastatic tumour leaks fluid into the pleural cavity, which is the basis for clinical signs of respiratory distress. A mass should be apparent in the lung.

Mesothelioma arises from the mesothelial cells lining the pleura. It implants widely on the pleura, and invades the underlying chest wall and lung. This is rare in domestic animals and, unlike in humans, is not associated with asbestos exposure.

Question:

Consider the three main routes by which bacteria enter the pleural cavity.

What additional lesions might be observed at necropsy, to suggest the likely route of infection?

(Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

Which two pleural conditions are most likely in a cat with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

Creamy pleural exudates could represent chylothorax or pyothorax. How would laboratory analysis of the fluid distinguish these? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

How does the reason for atelectasis and dyspnea differ in pneumothorax compared to hydrothorax? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Answer:

Consider the three main routes by which bacteria enter the pleural cavity.

What additional lesions might be observed at necropsy, to suggest the likely route of infection?

- Hematogenous: there may be fibrinous exudates on other serosal surfaces: pericarditis, peritonitis, polyarthritis, meningitis.

- External penetrating injury: there may be traumatic lesions in the chest wall.

- Extension from an underlying lung lesion: the primary lesion in the lung (e.g. bronchopneumonia) should be visible, with careful inspection.

Answer:

Which two pleural conditions are most likely in a cat with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy?

Hydrothorax or chylothorax.

Answer:

Creamy pleural exudates could represent chylothorax or pyothorax. How would laboratory analysis of the fluid distinguish these?

- Chylothorax: lymphocytes, and higher triglyceride concentration in pleural fluid vs serum.

- Pyothorax: neutrophils.

Answer:

How does the reason for atelectasis and dyspnea differ in pneumothorax compared to hydrothorax?

Hydrothorax: the simple presence of fluid leaves less room in the chest for lungs to expand. The physical presence of the fluid causes the atelectasis.

Pneumothorax ruins the ability to expand the lungs: expansion of the chest wall is now inefficient in creating a negative intrathoracic pressure, and the lungs don’t inflate as much as normal.